The Pittsburgh Press (February 18, 1945)

Ernie leaves Marianas –

Pyle believed in on Tokyo raids as first taste of war in Pacific

Preview of Jap POWs makes him creepy

Ernie Pyle has left the Marianas on his long trip to the Pacific front and last reports from him indicated that he is now aboard an American aircraft carrier – probably participating in one of the great naval actions now going in the Pacific.

“Covering this Pacific war is, for me, going to be like learning to live in a new city,” Ernie cabled from Honolulu. “The methods of war, the attitude toward it, the homesickness, the distances, the climate – everything is different from what we have known as the European War.”

Famous as the correspondent who has best pictured G.I. Joe in the campaigns in Africa, Sicily, Italy and France, Ernie finds the Pacific war an experience so new that he is constantly amazed.

And because he is a greenhorn in the Pacific, he has started to reveal the little details of that vast conflict which impress him and which will picture it to American readers as it has not been pictured before.

From Honolulu, Ernie’s first stop on his assignment with the Navy, he cabled:

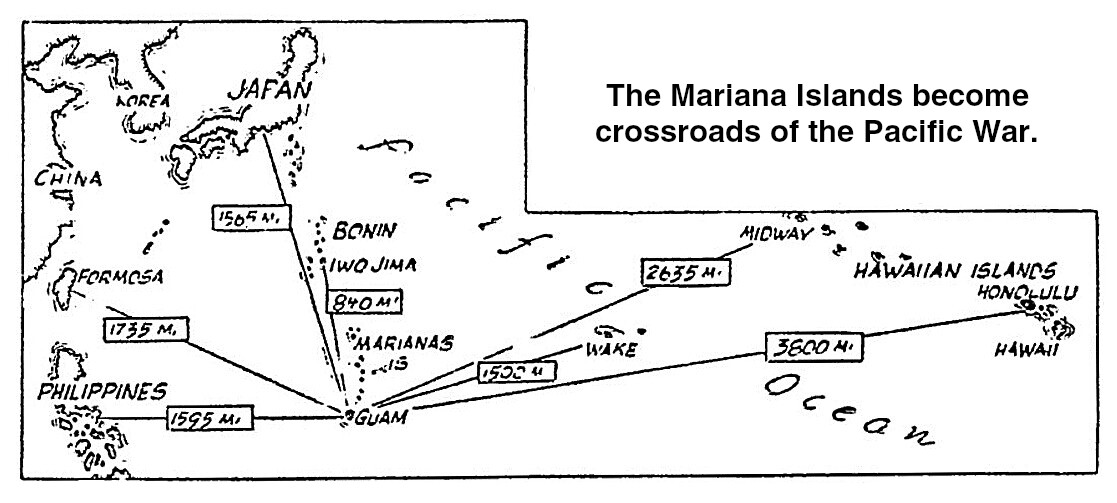

Distance is the main thing. I don’t mean distance from America so much, for our war in Europe is a long way from home too. I mean distances after you get right on the battlefield.

For the whole western Pacific is our battlefield now, and whereas distances in Europe are hundreds of miles at most, out here they are thousands. And there’s nothing in between but water.

You can be on an island battlefield, and the next thing behind you is a thousand miles away. One soldier told me the worst sinking feeling he ever had was when they had landed on an island and were fighting, and on the morning of D-3 he looked out to sea and it was completely empty. Our entire convoy had unloaded and left for more, and boy, did it leave you with a lonesome and deserted feeling.

Hundreds of people daily travel the 3,500 miles between Pearl Harbor and the Marianas, Ernie wrote, “as casually as you’d go to work in the morning.”

The days are warm and on our established island bases the food is good and the mail service is fast and there’s little danger from the enemy and the days go by in their endless sameness and they drive you nuts. They sometimes call it going “pineapple crazy.”

Our high rate of returning mental cases is discussed frankly in the island and service newspapers. A man doesn’t have to be under fire in the front lines finally to have more than he can take without breaking.

And another adjustment I’ll have to make is the attitude toward the enemy. In Europe, we felt our enemies, horrible and deadly as they were, were still people.

But out here I’ve already gathered the feeling that the Japanese are looked upon as something unhuman and squirmy – like some people feel about cockroaches or mice.

I’ve seen one group of Japanese prisoners in a wire-fenced courtyard, and they were wrestling and laughing and talking just as humanly as anybody. And yet they gave me a creepy feeling, and I felt in need of a mental bath after looking at them.

In the Marianas, from whence he later flew to join the aircraft carrier, Ernie cabled that “we are far, far away from everything that was home or seemed like home.”

He wrote:

The Pacific names are all new to me too, all except the outstanding ones. For those fighting one war do not pay much attention to the other war. Each one thinks his war is the worst and the most important war. And unquestionably it is.

We came to the Marianas by airplane from Honolulu. The weather was perfect, and yet so long and grinding was the journey that it eventually became a blur, and at the end I could not even remember what day we had left Honolulu, although actually it was only the day before.

We came in the same kind of plane that brought us from California – a huge four-motored Douglas transport, flown by the Naval Air Transport Service.

Our first step was at Johnston Island, four hours out from Honolulu. As it came into view, I was shocked at how tiny it is. It is hardly bigger than a few airplane carriers lashed together, and it hasn’t got a tree on it.

Yet it has been developed into an airfield that will take the biggest planes, and several hundred Americans live and work there.

From Johnston Island another long hop, this time at night, and then Ernie wrote:

Suddenly there were lights smack underneath us, lights of what seemed a good-sized little town, and then at last we were on the ground in an unbelievably hustling airport, teeming with men and planes and lights. The place was Kwajalein.

That’s not hard to pronounce if you don’t try too hard. Just say “Kwa-juh-leen.” It’s in the Marshall Islands. There, during last March and April, American soldiers and Marines killed 10,000 Japanese, and opened our island stepping-stone path straight across the mid-Pacific.

Even today our Seabees can’t dig a trench for a sewer pipe without digging up dead Japanese. But even so the island is transformed, as we so rapidly transform all our islands that are destroyed in the taking. It is a great air base now.

Ernie Pyle is fortunately participating in the Navy’s greatest Pacific actions. His dispatches from the aircraft carrier to which he is now attached will appear in The Pittsburgh Press daily. Watch for tomorrow’s Pyle story.