The Pittsburgh Press (February 16, 1945)

Roving Reporter

By Ernie Pyle

HONOLULU, Hawaii (delayed) – Covering this Pacific war is, for me, going to be like learning to live in a new city.

The methods of war, the attitude toward it, the homesickness, the distances, the climate – everything is different from what we have known in the European war.

Here in the beginning. I can’t seem to get my mind around it, or get my fingers on it. I suspect it will take months to get adjusted and get the “feel” of this war.

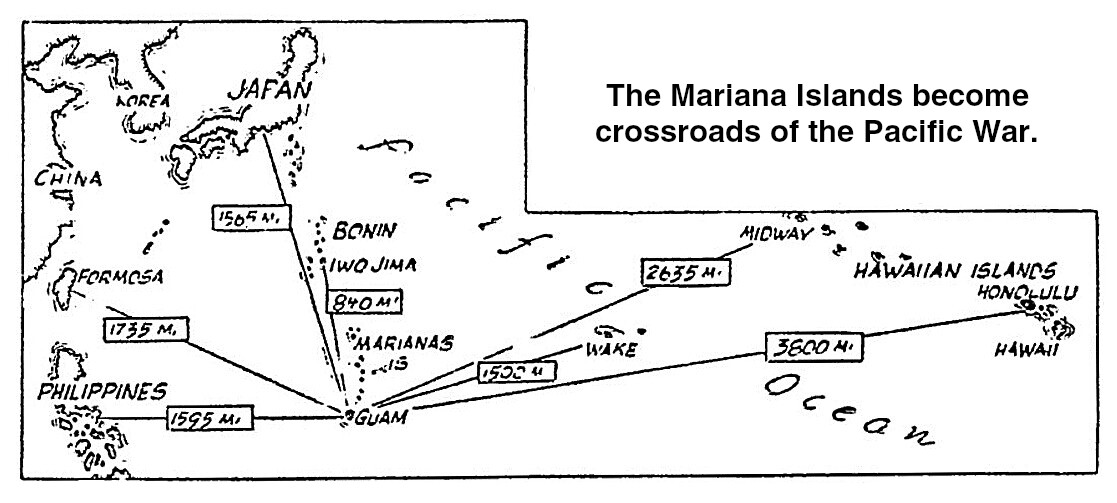

Distance is the main thing. I don’t mean distance from America so much, for our war in Europe is a long way from home too. I mean distances after you get right on the battlefield.

For the whole western Pacific is our battlefield now, and whereas distances in Europe are hundreds of miles at most, out here they are thousands. And there’s nothing in between but water.

You can be on an island battlefield, and the next thing behind you is a thousand miles away. One soldier told me the worst sinking feeling he ever had was when they had landed on an island and were fighting, and on the morning of D-3 he looked out to sea and it was completely empty. Our entire convoy had unloaded and left for more, and boy, did it leave you with a lonesome and deserted feeling.

Like slow-motion movies

As one admiral said, directing this war is like watching a slow-motion picture. You plan something for months, and then finally the great day comes when you launch your plans, and then it is days or weeks before the attack happens, because it takes that long to get there.

As an example of how they feel, the Navy gives you a slick sheet of paper as you go through here, entitled “Airline Distances in Pacific.” And at the bottom of it is printed “Our Enemy, Geography.” Logistics out there is more than a word; it’s a nightmare.

Here’s another example of their attitude toward distances in the Pacific–

At Anzio in Italy just a year ago, the Third Division set up a rest camp for its exhausted infantrymen. The rest camp was less than five miles from the front line, within constant enemy artillery range.

But in the Pacific, they bring men clear back from the western islands to Pearl Harbor to rest camps – the equivalent of bringing an Anzio Beachhead fighter all the way back to Kansas City for his two-weeks rest.

It’s 3,500 miles from Pearl Harbor to the Marianas, all over water, yet hundreds of people travel it daily by air as casually as you’d go to work in the morning.

Another enemy

And there is another enemy out here that we did not know so well in Europe – and that is monotony. Oh sure, war everywhere is monotonous in its dreadfulness. But out here even the niceness of life gets monotonous.

The days are warm and on our established island bases the food is good and the mail service is fast and there’s little danger from the enemy and the days go by in their endless sameness and they drive you nuts. They sometimes call it going “pineapple crazy.”

Our high rate of returning mental cases is discussed frankly in the island and service newspapers. A man doesn’t have to be under fire in the front lines finally to have more than he can take without breaking.

He can, when isolated and homesick, have more than he can take of nothing but warmth and sunshine and good food and safety – when there’s nothing else to go with it, and no prospect of anything else.

Japs are different

And another adjustment I’ll have to make is the attitude toward the enemy. In Europe, we felt our enemies, horrible and deadly as they were, were still people.

But out here I’ve already gathered the feeling that the Japanese are looked upon as something unhuman and squirmy – like some people feel about cockroaches or mice.

I’ve seen one group of Japanese prisoners in a wire-fenced courtyard, and they were wrestling and laughing and talking just as humanly as anybody. And yet they gave me a creepy feeling, and I felt in need of a mental bath after looking at them.

I’ve not yet got to the front, or anywhere near it, to find out how the average soldier or sailor or Marine feels about the thing he’s fighting. But I’ll bet he doesn’t feel the same way our men in Europe feel.