Sammy Kaye’s Sunday Serenade (NBCR), December 7, 2 p.m. EST:

Great Plays: The Inspector General (NBCB), 2 p.m. EST:

Commander in Chief, U.S. Pacific Command (December 7, 1941)

NPM 1516

Z 0F2 1830 0F3 0F4 1F0 O

(U R G E N T)

FROM

CINCPAC

DATE-TIME OF ORIGIN

070758A December

TO FOR ACTION

CINCLANT

TO FOR INFORMATION (INFO)

CINCAF

OPNAV

AIR RAID ON PEARL HARBOR X THIS IS NOT DRILL

DISTRIBUTION:

38… ACTION.

10/11… 12… 13… 16… OPDO… 38W…

20… NAVAIDE… 05…

BJ18507DECMX

Statement by the Press Secretary

Immediate Release to Press and Radio

December 7, 1941 2:25 p.m. EST

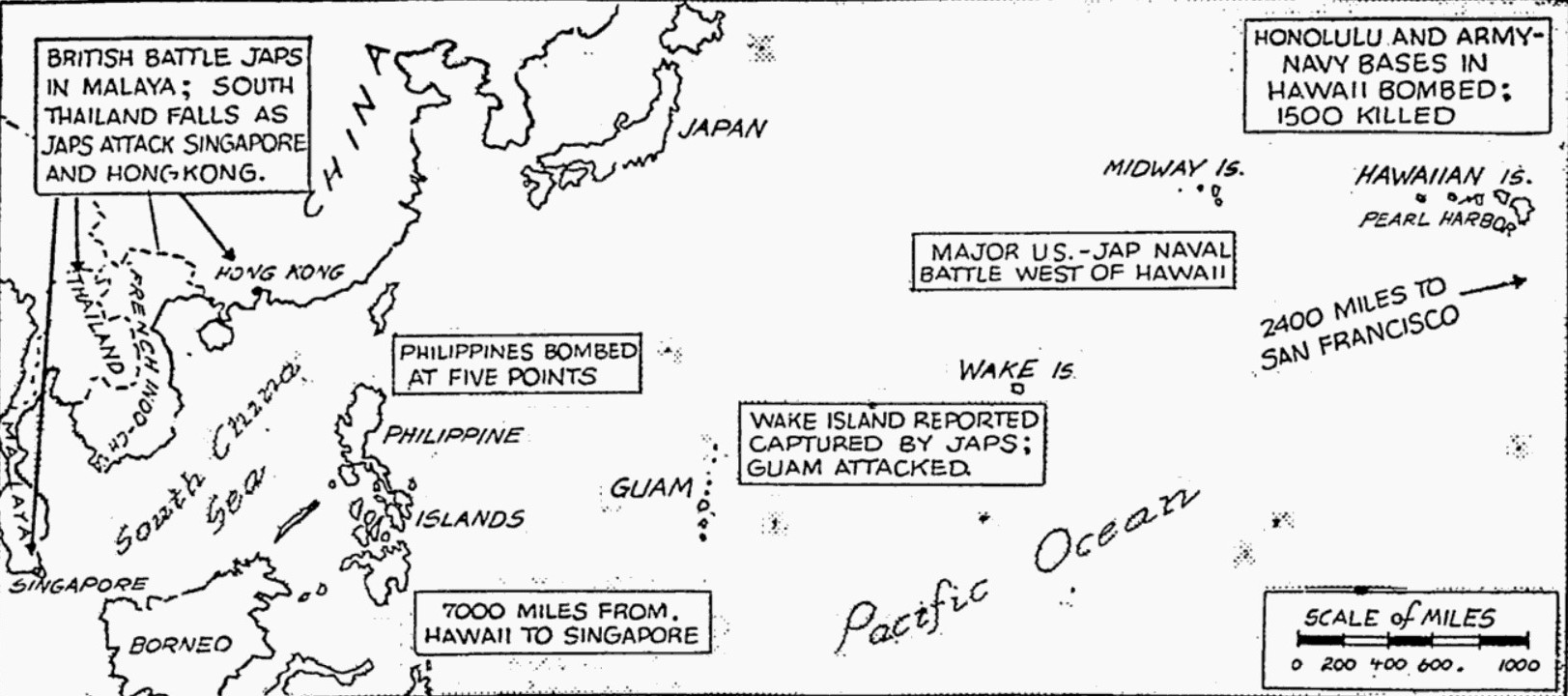

The Japanese have attacked Pearl Harbor from the air and all naval and military activities on the island of Oahu, the principal American base in the Hawaiian Islands.

S T E

The above statement given to:

THE AP

INS

UP

NBC

CBS

WOL-MUTUAL

TRANS-RADIO PRESS

WASHINGTON EVENING STAR

WASHINGTON POST

WASHINGTON TIMES-HERALD

THE NEW YORK TIMES

THE NEW YORK HERALD-TRIBUNE

THE NEW YORK DAILY NEWS

THE NEW YORK JOURNAL OF COMMERCE

BRITISH PRESS SERVICE

BALTIMORE SUN

PHILADELPHIA RECORD

CHICAGO TRIBUNE

Interruption of Giants-Dodgers football game (WOR), 2:26 p.m. EST:

AIRPLANES IDENTIFIED AS JAPANESE HAVE ATTACKED THE AMERICAN NAVAL BASE AT PEARL HARBOR

University of Chicago Roundtable: ‘Canada: A Neighbor at War’ (NBCR), 2:29 p.m. EST:

Statement by the Press Secretary

Immediate Release to Press and Radio

December 7, 1941 2:30 p.m. EST

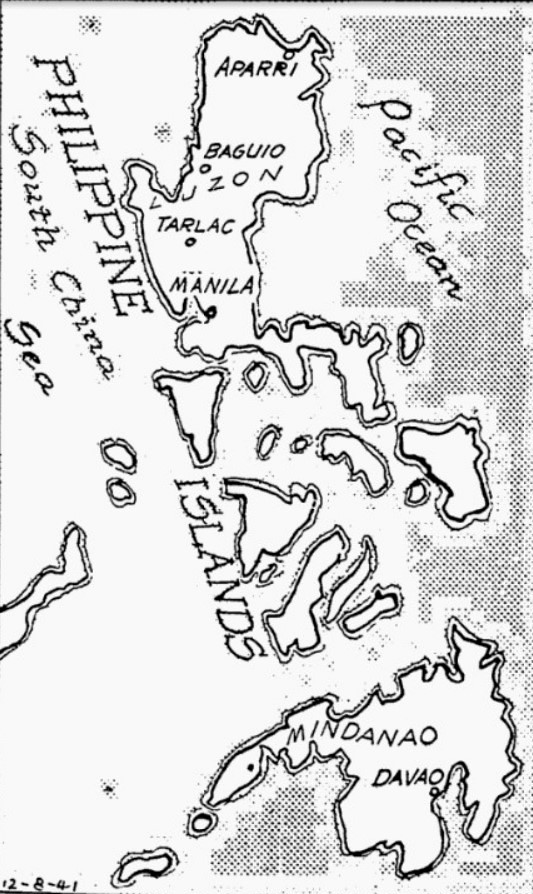

A second air attack is reported. This one has been made on Army and Navy bases in Manila.

S T E

The above statement given to:

THE AP

INS

UP

NBC

CBS

WOL-MUTUAL

TRANS-RADIO PRESS

WASHINGTON EVENING STAR

WASHINGTON POST

WASHINGTON TIMES-HERALD

THE NEW YORK TIMES

THE NEW YORK HERALD-TRIBUNE

THE NEW YORK DAILY NEWS

THE NEW YORK JOURNAL OF COMMERCE

BRITISH PRESS SERVICE

BALTIMORE SUN

PHILADELPHIA RECORD

CHICAGO TRIBUNE

2 HITS ON AIRPORT HICKAM FIELD OIL TANKS SET AFIRE PEARL HARBOR SKY FILLED WITH AMERICAN PURSUIT SHIPS

The World Today (CBS), 2:31 p.m. EST:

TRANSPORT SUNK 1300 MILES FROM SAN FRANCISCO APPARENTLY LOADED WITH LUMBER COMMERCIAL U.S. SHIP SUNK 700 MILES OFF COAST NAVAL BATTLE OFF HONOLULU

The Wake Up America Radio Forum (NBCB), 3 p.m. EST:

The Bob Becker Show (NBCR), 3 p.m. EST:

H. V. Kaltenborn (NBCR), 3:15 p.m. EST:

JAPANESE AIRPLANES BOMBING HONOLULU ADVERTISER BUILDING STRUCK KGU BUILDING HAS NEAR MISSES

FIVE PEOPLE KILLED IN HONOLULU CABINET MEETING AT 8 P.M. TONIGHT

Listen America (NBCR), 3:30 p.m. EST:

PARACHUTE TROOPS SIGHTED OFF HONOLULU

Clip from the New York Philharmonic Society broadcast (CBS), 3:35 p.m. EST (includes I Can Hear It Now 1948 recreation of John Daly’s broadcast):

JAPANESE NATIONALS IN PANAMA TAKEN INTO CUSTODY

WHITE HOUSE ANNOUNCES THAT VERY HEAVY CASUALTIES HAVE BEEN RECEIVED BY OUR PEOPLE IN HONOLULU

U.S. Navy Department (December 7, 1941)

MEMORANDUM FOR THE PRESIDENT

December 7, 1941, 3:50 p.m.

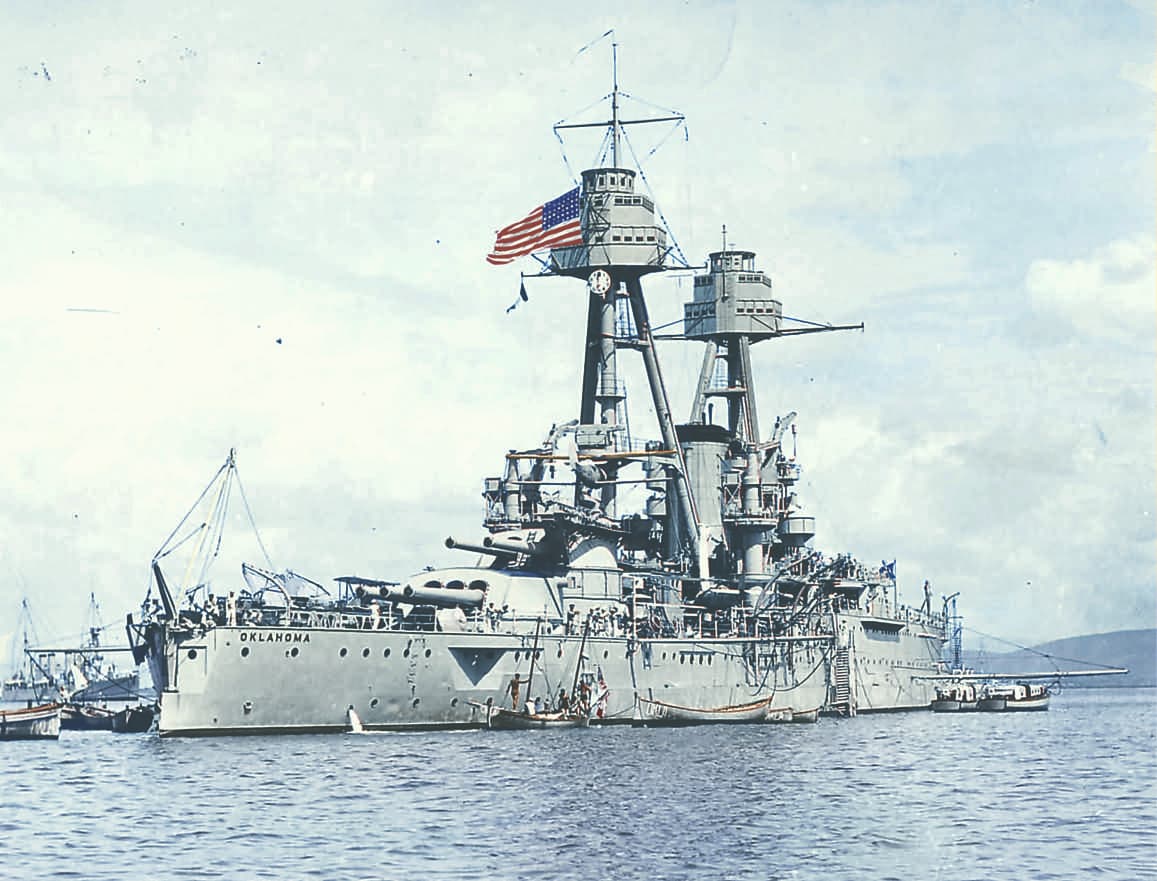

The Japs attacked Honolulu time about eight o’clock this morning. The first warning was from a submarine that was outside the harbor which was attacked by a destroyer with depth bombs. Result unknown. Another submarine was sunk by aircraft. They attacked with aircraft, with bombs and torpedoes. At least two aircraft were known to have a swastika sign on them. The attacks were in two divisions; first on the airfields and then on the navy yard. Severe damage. The Oklahoma has capsized in Pearl Harbor. The Tennessee is on fire with a bad list, and the Navy Yard is attempting to drydock her.

No. 1 drydock was hit by bombs. The Pennsylvania was in deck and apparently undamaged. There were two destroyers hit in drydock, one of them blew up. There was one destroyer in a floating drydock which is on fire and the deck is being flooded. Two torpedoes hit the sea wall between the Helena, which is 10,000 tons–6 in. cruiser, and the Oglala. The Oglala is heavily listed and can probably not be saved. She is on fire and is an old minelayer. The powerhouse at Pearl Harbor was hit but is still operating. The Honolulu powerhouse was presumably hit because there is no power on it. The airfields at Ford Island, Hickam, Wheeler and Kaneohe were attacked. Hangers on fire and Hickam Field fire is burning badly. The PBYs outside of hangars are burning. Probably heavy personnel casualties but no figures. So far as Block knows Honolulu was not hit. He does not know how many aircraft were brought down but he know personally of two. They have both been so busy he has not contacted Kimmel. There are two task forces at sea, each one of them with a carrier. He knows nothing further on that except that they are at seas. This came over the telephone and we are getting nothing out here whatever. Mr. Vincent called but I have given out nothing, pending further word from you. The Japanese have no details of the damage which they have wrought.

National Vespers (NBCB), 4 p.m. EST:

Sylvia Marlowe & Richard Dyer-Bennet (NBCR), 4 p.m. EST:

WCAE Pittsburgh bulletin, 4 p.m. EST:

CBS News update, 4 p.m. EST:

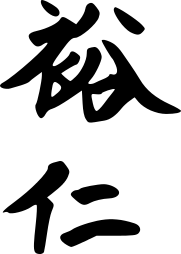

Imperial GHQ (December 8, 1941)

![]()

大本営陸海軍部、十二月八日午前六時

帝國陸海軍は夲八日未明、西太平洋においてアメリカ、イギリス軍と戰鬪狀態に入れり。

Broadcast (NHK), 6 p.m. JST (December 8):

News (NBCB), 4:30 p.m. EST:

News (NBCR), 4:30 p.m. EST:

TWO AMERICAN BATTLESHIPS SUNK BETWEEN 60 TO 200 DIVE BOMBERS PARTICIPATED 5 JAP PLANES DOWN

GREAT LOSS OF LIFE AND PROPERTY IN HAWAII NAVY AND ARMY FIGHTING AND ON SEA AND AIR AT THIS MOMENT AIR RAID WARDENS WARNED TO BE ON NOTICE IN U.S.

USS OKLAHOMA HIT AND SET ON FIRE

The Moylan Sisters (NBCB), 5 p.m. EST:

Metropolitan Opera Auditions of the Air (NBCR), 5 p.m. EST:

Broadcast snippets (BBC), 5 p.m. EST:

JAPS HAVE ATTACKED HMS PETEREL, ALSO REPORTED SUNK

350 MEN KILLED WHEN HICKAM FIELD WAS BOMBED 6 DEAD, 200 OTHERS IN ONE HOSPITAL ALONE ENEMY PARACHUTE TROOPS IN HONOLULU ANOTHER SHIP REPORTED ATTACKED 700 MILES OFF SAN FRANCISCO CAVITE AND LUZON ALSO ATTACKED ALL OFFICERS WEAR UNIFORM TOMORROW

News (NBCB), 5:15 p.m. EST:

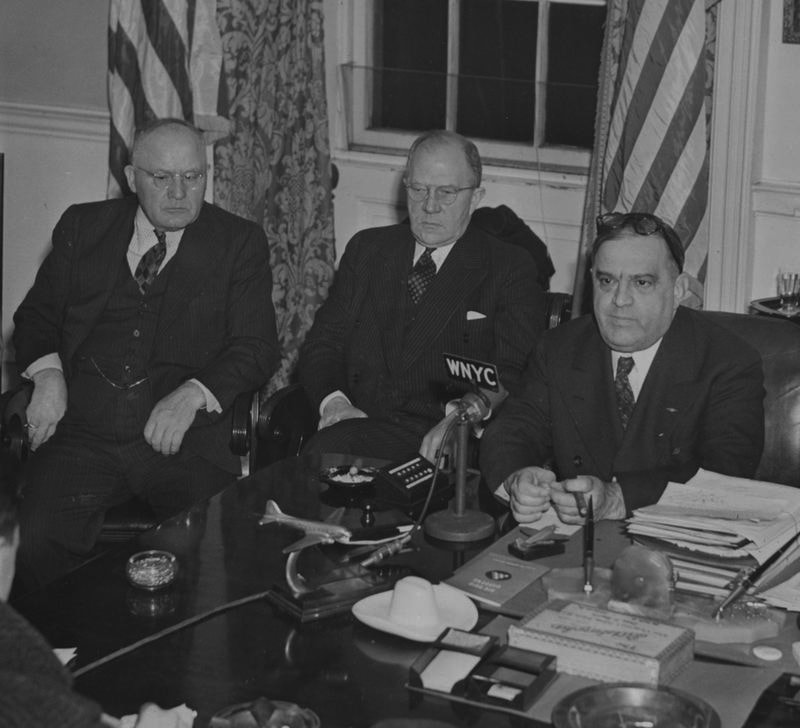

Address by Mayor La Guardia of New York City

December 7, 1941, 5:15 p.m. EST

New York City

Broadcast (WNYC):

I want to warn the people of this city that we are in an extreme crisis.

Anyone familiar with world conditions will know that the Nazi government is masterminding Japanese policy and the action taken by the Japanese government this afternoon. It was carrying out the now known Nazi technique of murder by surprise.

So, there is no doubt that the thugs and gangsters now controlling the Nazi government are responsible and have guided the Japanese government in the attack on American territory and the attack on the Philippine Islands.

Therefore, I want to warn the people of this city and on the Atlantic Coast that we must not and cannot feel secure or assured because we are on the Atlantic Coast and the activities this afternoon have taken place in the Pacific. We must be prepared for anything, at any time.

As Mayor of the City of New York and on my own responsibility, I have ordered all Japanese subjects to remain in their homes until their status is determined by our federal government. The offices of the Japanese Consulate General are now being protected by the Police Department. Until the status of the Japanese Consul General is determined by our federal government, he will be protected and escorted to and from his office.

I have ordered, on my own responsibility, the Japanese club in this city to be closed, in keeping with my order that all Japanese subjects must remain in their homes until their status is determined and further orders issued.

As Mayor, I have been in communication and in touch with all the necessary federal agencies in this city. There is full and complete cooperation. I have reported the action taken by the city government to the governor of our state. I have been in communication and in touch with the authorities in Washington.

I now want to appeal to the people of our city to be calm. There is no need of being excited or unduly alarmed. But I want to repeat what I said before that we are not out of the danger zone by any means, and to be prepared to receive instructions, and to cooperate at any time that instructions are given to the citizens of this city, and to cooperate with any plan that may be announced for their protection and the protection of their homes.

As United States Director of Civilian Defense, I am communicating with all regional officers instructing them to communicate with the governors of the state within their region and asking the governors, state and local councils to intensify the training of air raid wardens and auxiliary fire forces. More detailed instructions to the regional directors will follow.

To all air raid wardens and auxiliary firemen now enrolled, I’m asking them to prepare to attend daily drills. It is necessary that we be on the alert at all times.

My friends, we must toughen up! We have our homes and our lands to defend now! We must remain cool and yet determined. We are aware of the danger ahead, but unafraid. In the meantime, know that your city government is on the job and looking after your welfare and comfort and safety.

Tomorrow, in all likelihood, we will know exactly where we stand when we hear from Washington.

We can all rest assured that our national government will take the necessary steps to protect our lands and our institutions. And we can also be certain that our great president, at this very moment, is taking just those necessary protective steps.

So, in the meantime, good night and we will remain on the job.

JAPS ANNOUNCE A STATE OF WAR WITH U.S. AND GREAT BRITAIN IN THE WESTERN PACIFIC EFFECTIVE DAWN MONDAY DECEMBER 8

NOTICE FROM GEN WEYMSS OF THE BRITISH STAFF MISSION IN WASHINGTON THAT ORDERS HAVE BEEN ISSUED TO ALL BRITISH UNITS TO TAKE ACTION AGAINST ALL JAPANESE FORMATIONS WHEREVER FOUND

It’s Wheeling Steel! (NBCB), 5:30 p.m. EST:

The Nichols Family of Five (NBCR), 5:30 p.m. EST:

Pittsburgh sabotage bulletin (KDKA), 5:30 p.m. EST:

Honolulu Star-Bulletin (December 7, 1941)

OAHU BOMBED BY JAPANESE PLANES

Six known dead, 21 injured, at emergency hospital

Attack made on island’s defense areas

BULLETIN

SAN FRANCISCO (AP by Trans-Pacific Telephone) – President Roosevelt announced this morning that Japanese planes had attacked Manila and Pearl Harbor.

WASHINGTON (UP) – A White House announcement detailing the attack on the Hawaiian Islands read: “The Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor from the air and all naval and military activities on the island of Oahu, principal American base in the Hawaiian Islands.”

Oahu was attacked at 7:55 this morning by Japanese planes.

The Rising Sun, the emblem of Japan, was seen on plane wingtips.

Wave after wave of bombers streamed through the cloudy morning sky from the southwest and flung their missiles on a city resting in a peaceful Sabbath calm.

According to an unconfirmed report received at the governor’s office, the Japanese force that attacked Oahu reached island waters aboard two small airplane carriers.

It was also reported that at the governor’s office, either an attempt had been made to bomb the USS Lexington, or that it had been bombed.

Within 10 minutes, the city was in an uproar. As bombs fell in many parts of the city, and in defense areas, the defenders of the islands went into quick action.

Army intelligence officers at Fort Shafter officially announced shortly after 9 a.m. the fact of the bombardment by an enemy but long previous Army and Navy had taken immediate measures in defense.

Oahu is under a sporadic air raid. Civilians are ordered to stay off the streets until further notice.

Civilians ordered off streets

The Army has ordered that all civilians stay off the streets and highways and not use telephones.

Evidence that the Japanese attack has registered some hits was shown by three billowing pillars of smoke in the Pearl Harbor and Hickam Field areas.

All Navy personnel and civilian defense workers, with the exception of women, have been ordered to duty at Pearl Harbor.

The Pearl Harbor Highway was immediately a mass of racing cars.

A trickling stream of injured people began pouring into the city emergency hospital a few minutes after the bombardment started.

Thousands of telephone calls almost swamped the Mutual Telephone Company, which put extra operators on duty. At the Star-Bulletin office, the phone calls deluged the single operator and it was impossible for this newspaper, for some time, to handle the flood of calls. Here also, an emergency operator was called.

Hour of attack: 7:55 a.m.

An official Army report from department headquarters, made public shortly before 11 a.m., is that the first attack was at 7:55 a.m. Witnesses said they saw at least 50 airplanes over Pearl Harbor.

The attack centered in the Pearl Harbor area, Army authorities said, “The Rising Sun was seen on the wingtips of the airplanes.”

Although martial law has not been declared officially, the city of Honolulu was operating under M-Day conditions.

It is reliably reported that enemy objectives under attack were Wheeler Field, Hickam Field, NAS Kaneohe Bay and Pearl Harbor.

Some enemy planes were reported shot down. The body of the pilot was seen in a plane burning at Wahiawa.

Oahu appeared to be taking calmly after the first uproar of queries.

Anti-aircraft guns in action

First indication of the raid came shortly before 8 a.m. when anti-aircraft guns around Pearl Harbor began sending up a thunderous barrage.

At the same time, a vast cloud of black smoke arose from the naval base and also from Hickam Field where flames could be seen.

Bomb near governor’s mansion

Shortly before 9:30 a.m., a bomb fell near Washington Place, the residence of the governor. Gov. Poindexter and Secretary Charles M. Hite were there.

It was reported that the bomb killed an unidentified Chinese man across the street in front of the Schuman Carriage Company building where windows were broken.

C. E. Daniels, a welder, found a fragment of a shell or bomb at South and Queen Streets which he brought into the City Hall. This fragment weighed about a pound.

At 10:05 a.m. today, Gov. Poindexter telephoned to the Star-Bulletin announcing he has declared a state of emergency for the entire territory. He announced that Edouard L. Doty, executive secretary of the major disaster council, has been appointed director under the M-Day law’s provisions.

Gov. Poindexter urged all residents of Honolulu to remain off the street, and the people of the territory to remain calm.

Mr. Doty reported that all major disaster council wardens and medical units were on duty within a half-hour at the time the alarm was given.

Workers employed at Pearl Harbor were ordered at 10:10 a.m. not to report at Pearl Harbor.

The mayor’s major disaster council was to meet at the City Hall at about 10:30 this morning.

At least two Japanese planes were reported at Hawaiian Department headquarters to have been shot down. One of the planes was shot down at Fort Kamehameha and the other back of the Wahiawa Courthouse.

Damage done around the city

At 9:38 a.m., a live wire was reported down at Richards and Beretania Streets.

At 9:42 a.m., Nuuanu above Vineyard, a gas line was leaking.

At 9:44 a.m., at 2840 Kalihi St., a bomb on the road. There was a mysterious Japanese in a tent camped near there.

At 9:45 a.m., at 2683 Pacific Heights Rd., a bomb struck a house.

Report airplane crashes, Wahiawa

It was reported that an airplane, nationality undisclosed, crashed near the Hawaiian Electric Company plant at Wahiawa. It was destroyed by fire as were two houses near which it fell. The Army and police flung a guarding cordon around the location and civilians were kept at a distance.

Many injuries are reported

An unidentified Army witness arriving at Hawaiian Department headquarters about 9:30 a.m. reported that two oil tanks at Pearl Harbor were ablaze.

A bomb was reported to have struck at 9:25 this morning near 624 Ala Moana.

At 8:35 a.m., the Police Department broadcast a statement to all officers to warn persons to leave the streets and return to their homes. All soldiers, sailors and Marines off duty were ordered to report at once to their respective posts and stations.

Residents were ordered by radio not to use their telephones.

At 8:17 a.m., a Honolulan at Pearl Harbor Gate heard Marines ordered out.

Bomb hits home in Damon Tract

At 8:05 a.m., according to a police report, a bomb crashed through the kitchen of the home of Thomas Fujimoto, 610 East Rd., Damon Tract, while the family of three was eating breakfast. No one was injured, according to the police.

According to another police report, several persons were injured by a bomb dropping in Kalihi Street.

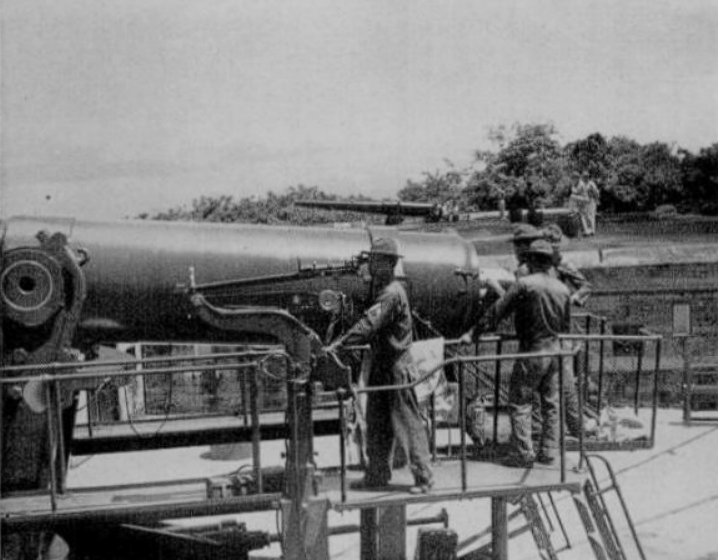

At 9:10 a.m., a report was made to the police that a wave of five dive bombers attacked the oil tanks at Pearl Harbor, the planes flying as low as a hundred feet.

At 9:10 a.m., the Pearl Harbor housing area was reported ordered evacuated.

At 9:12 a.m., according to the police, two planes were reported to have dropped bombs on Pearl Harbor Road.

At 9:13 a.m., the police received a report that a house on Alewa Heights had been bombed.

At 9:17 a.m., Damon Tract residents, according to a police report, were ordered evacuated and the police said nearby residents were cooperating in helping them leave the area.

Incendiary bomb at Fort and School

A wooden-frame house was split in half by an incendiary bomb at Fort and School Streets, about 9:20 a.m. Fire Department could not stop the flames. About 100 firemen are operating out of headquarters at Fort and Beretania Streets.

All departments of the Fire Department have been called at headquarters. At present, there are six companies operating. Three companies were sent to Hickam Field this morning. The firetrucks are sent out to investigate a fire and, after investigating and doing all possible to put it out, return to headquarters for the next assignment.

At 9:25 a.m., a bomb broke a power line at 625 Ala Moana.

At 9:26 a.m., a man was injured at Richards and Beretania Streets.

At 9:27 a.m., a sampan, heavily laden, was reported off Moanalua.

At 9:30 a.m., a bomb fell at Kuhio and Kalakaua Avenues. No one was hurt.

At 9:34 a.m., a Japanese plane was reported shot down at Wahiawa.

At 9:32 a.m., a bomb fell near E Street in Damon Tract.

At 9:36 a.m., a bomb hit on North School Street.

At 9:50 a.m., all truck drivers and motorboat operators of the U.S. Engineers and Hawaiian Constructors were ordered to report at Kewalo Basin.

All Legionnaires who are in the emergency police force were reporting to the police station. All Legionnaires who are not on the emergency police force are being held at the Legion Clubhouse, Kapiolani Boulevard, for call.

The emergency disaster council, headed by Maj. Robert Faus, was called and are at their posts at schoolhouses. Col. James R. Mahaffay and Joe McGettigan, coordinators, were on duty.

At 10:08 a.m., two Japanese were reported near the water tank at Sierra Drive and Wilhelmina Rise.

At 10:22 a.m., Yuz Marimatsu reported that his house at 758 Kaaloa St. was bombed. A five-inch shell went directly through the house, injuring no one.

A house at 1807 Liliha St. was reported bombed with no injuries.

Police have been ordered to guard vital spots throughout the city where soldiers have not yet been stationed.

Hundreds see city bombed

Hundreds of Honolulans who hurried to the top of Punchbowl seen after bombs began to fall, saw spread out before them the whole panoramas of surprise attack and defense.

Far off over Pearl Harbor, the white sky was polka-dotted with anti-aircraft smoke.

Rolling away from the Navy base were billowing clouds of ugly black smoke. Sometimes, a burst of flame reddened the black sources of the smoke.

Out from the silver-surfaced mouth of the harbor, a flotilla of destroyers streamed to battle, smoke pouring from their stacks.

Editorial: Hawaii meets the crisis

Honolulu and Hawaii will meet the emergency of war today as Honolulu and Hawaii have met emergencies in the past – coolly, calmly and with immediate and complete support of the officials, officers and troops who are in charge.

Gov. Poindexter and the Army and Navy leaders have called upon the public to remain calm, for civilians who have an essential business on the streets to stay off; and for every man and woman to do his duty.

That request, coupled with the measures promptly taken to meet the situation that has suddenly and terribly developed, will be needed.

In this crisis, every difference of race, creed and color will be submerged in the one desire and determination to play the part that Americans always play in crisis.

SECWAR HAS ADVISED ALL PLANTS HAVING DEFENSE CONTRACTS TO TAKE ALL PRECAUTIONS LA GUARDIA REQUESTS ALL JAPS IN U.S. TO STAY AT HOME UNTIL THEIR STATUS HAS BEEN DETERMINED

CANADIAN PRIME MINISTER HAS CALLED A CABINET MEETING FOR 6 P.M. TONIGHT

BRITISH ADMIRALTY: AN ATTEMPTED LANDING IS BEING MADE AT KHOTA BARU BY A FORCE OF THREE TO FIVE SHIPS. KHOTA BARU IS ABOUT 20 MILES SOUTH OF THE BRITISH MALAY STATES-THAILAND BORDER, AT 6 DEGREES NORTH 102 DEGREES EAST