‘Yesterday is tomorrow… when will we ever stop’

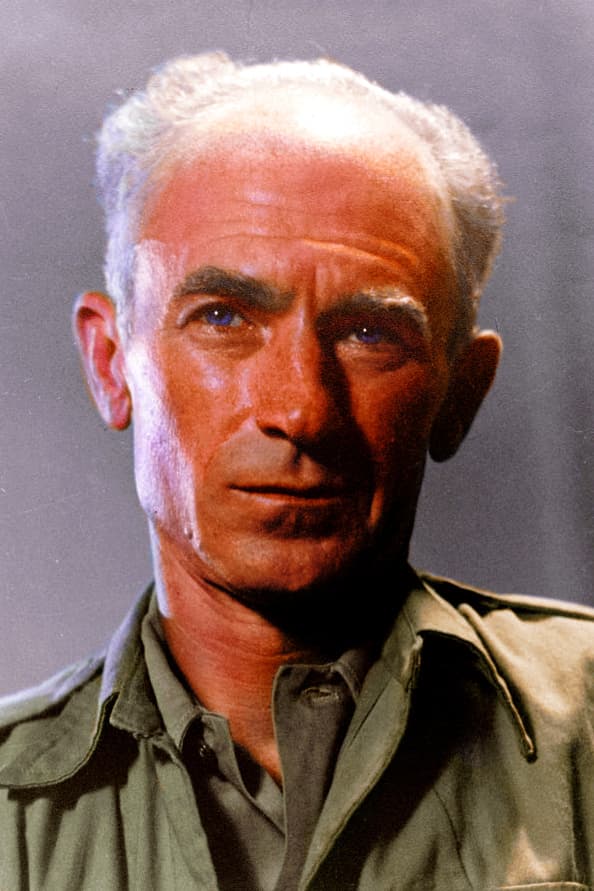

Pyle’s articles soon attracted a vast audience at home, and soldiers who had received clippings of his column in their mail began to look upon him as their laureate. They would yell “Hi, Ernie” when they glimpsed him in the field, and whenever a press car passed troops on a toad, scores would shout, “Is Ernie Pyle in that car?” He was showered with gifts of food, souvenirs, good-luck trophies. One unit gave him a captured German Volkswagen. In return he handed out hundreds of cigarettes and scores of lighters sent to him by admirers at home.

As the months passed somber tones crept into Pyle’s columns. In North Africa, despite perils and bloodshed, he had felt that the physical discomforts of war – the animal-like existence, cold, sleeplessness, hunger for women – caused soldiers greater distress than fear of death or the horror of killing. He confessed he had at first enjoyed the simplicity of life in the field and had found the sense of danger exhilarating. But in the bitter defiles of Italy, he began to be oppressed by the terrible weariness of mind and soul that overcame men after weeks under fire. “It’s the constant roar of engines,” he wrote, “and the perpetual moving and the never settling down and the go, go, go, night and day, and on through the night again. Eventually it all works itself into an emotional tapestry of one dull dead pattern – yesterday is tomorrow and Troina is Randazzo and when will we ever stop and, God, I’m so tired!” Ernie himself came to feel exhausted and written out. One night after a spell in the wet mountains he attempted a column about some dead men – among them a Capt. Waskow – whose bodies had been brought down from a bleak ridge where fighting had raged for days. The story refused to take shape and several times he almost gave up. When it was finished, dubious of its merit, he asked Don Whitehead of the Associated Press to read it. Whitehead said, “I think it’s the most beautiful piece you’ve ever done.” Ernie declined to be cheered up. Whitehead then passed the column on to Clark Lee, Dick Tregaskis and several other correspondents, all of whom confirmed his judgment. But Ernie decided they were simply trying to be nice and went to bed miserable. Back home the exquisite understated emotion and quiet imagery of his now-famous Waskow column stirred newspaper editors from coast to coast. The New York World-Telegram headlined it “An Epic Story by Ernie Pyle.” The Washington News devoted its entire front page to it.

Pyle had the narrowest escape of his war career a few weeks later. Attracted always to the scenes of deadliest combat, he went to the Anzio beachhead. Early one morning a German bomber dropped a stick of 500-pounders squarely across a villa which was serving as press headquarters. Pyle’s upstairs room, where he had been lying in bed, was demolished. But he miraculously emerged from mountains of rubble and shattered glass with only a scratch on his check. After that his colleagues called him “Old Indestructible.” It was his last adventure in Italy. The invasion of Europe was brewing and in April 1944 Ernie flew to England to await D-Day.

Premonitions of death

Pyle’s working habits had subtly and involuntarily changed. In North Africa he had been able to move about as he pleased. By the time he reached France, he was so famous he could scarcely walk down a village street without soldiers of all ranks accosting him and requesting his autograph. He discovered that G.I.’s had come to regard mention of their names in his column as comparable to an official citation. Commanding officers besought him to visit their special units, then engulfed him with time-consuming hospitality. Pyle found that these flattering attentions interfered with his work and he regretted his loss of freedom. Yet his innate kindness and courtesy made it impossible for him to brush off admirers, even at embarrassing moments. One day, while accompanying an infantry company that had been assigned to clean out a strong point in Cherbourg, he got caught in a duel between an American tank and an enemy pillbox. While Ernie and another correspondent watched from a doorway, the tank was hit by a German shell and knocked out. “Let’s get out of here,” said the other correspondent and sprinted down the street. It was almost an hour before Ernie rejoined him. “Some of the fellows that jumped out of that tank knew me from my picture,” he apologized, “so I had to stop and talk.”

The spiritual torment and revulsion against war that had oppressed him in Italy descended on him even more darkly among the hedgerows of Normandy, though few readers guessed what underlay the warm, easy and frequently humorous content of his columns. He had been with the war nearly two and a half years, had lived longer in the front lines and witnessed more fighting than most other correspondents and indeed than most soldiers. He found himself increasingly haunted by a premonition of his own death. “Instead of becoming used to danger,” he told a friend in Normandy, “I become less used to it as the years go by. I’ve begun to feel I have about used up my chances.” The experience that finally convinced Pyle he needed a vacation was the battle of St. Lô when American planes accidentally bombed the front lines of American forces on the ground. To soften up the Germans an epic concentration of 2,500 bombers had been ordered to blast an area behind the St. Lô-Marigny Road. The dividing line between U.S. and German troops had been marked out by strips of colored cloth. “The flight across the sky was slow and studied,” Pyle wrote. “I’ve never known a storm, or a machine, or any resolve of man that had about it the aura of such ghastly relentlessness… And then the bombs came. They began like the crackle of popcorn and almost instantly swelled into a monstrous fury of noise that seemed surely to destroy all the world ahead of us.” Little by little a gentle wind carried the curtains of dust and smoke back over the American lines, and soon successive flights of bombers aiming at the smoke line began dropping their death cargo on Americans. As the bombs fell about him Pyle dived into a wagon shed beside an officer. “We lay with our heads slightly up – like two snakes – staring at each other in a futile appeal, until it was over… There is no description of the sound and fury of those bombs except to say it was chaos, and a waiting for darkness.” Pyle later confided to friends that this episode had been the most horrible and horrifying of all his war experiences. “I don’t think I could go through it again and keep my sanity,” he said.

After St. Lô, Ernie pulled back of the lines and slept for nearly 24 uninterrupted hours. Then for three days he found himself unable to write a line. He remained in France long enough to witness the liberation of Paris. Then he headed home. “I’m leaving for one reason only,” he wrote in his farewell column, “–because I have just got to stop. ‘I’ve had it,’ as they say in the Army… My spirit is wobbly and my mind is confused… All of a sudden it seemed to me that if I heard one more shot or saw one more dead man, I would go off my nut.” He was not exaggerating. Analyzing his mental state several months later, he confessed, “I damn near had a war neurosis. About two weeks more and I’d have been in a hospital. I’d become so revolted, so nauseated by the sight of swell kids having their heads blown off, I’d lost track of the whole point of the war. I’d reached a point where I felt that no ideal was worth the death of one more man. I knew that was a short view. So, I decided it was time for me to back off and look at it in a bigger way.”

‘If I can survive America…’

Hundreds of soldiers wrote Ernie goodbye letters, saying in effect “We understand.” Not one reproached him for leaving. And many expressed relief that he was leaving danger behind. Back home his fellow countrymen welcomed him like a Congressional Medal hero. Strangers rushed up to him on street corners to wring his hand and express their esteem. One night he went to a Broadway show. Before he reached his seat a swelling buzz of recognition focused every eye on the back of his balding head. Gratified but at the same time terrified by such attentions, Pyle took refuge in the sanctuary of a hotel room and remained there during most of his stay in New York while his friend, Lee Miller, managing editor of the Scripps-Howard Newspapers, Washington Bureau, stood guard at the never-silent telephone, shielding him from impresarios, autograph hunters and other well-meaning intruders. Friends noticed he appeared at ease only in the company of G.I.’s. Whenever some veteran of Tunisia spied him and yelled, “Hi Ernie, remember Kasserine Pass?” Pyle would fondly throw his arms around him and drag him off to a bar for a session of reminiscence. “If I can survive America,” Ernie told Miller, “I can survive anything.”

Even at home in Albuquerque he found it difficult to relax. There too the phone chattered and sightseers cruised past his house, seeking a glimpse of Ernie sunning on his terrace. Mail kept him busy three hours a day. In addition to his manifold professional distractions, Ernie’s vacation was marred by anxiety over the health of his wife. She had been recurrently ill for several years, and this factor had aggravated the depression that shadowed his last months overseas. His pleasure on returning home was vitiated by the fact that Jerry was in the hospital on the day he arrived. One afternoon when his melancholy was deepest and chances of her ultimate recovery seemed dim, he told Cavanaugh, “Here I am with fame and more money than I know what to do with – and what good does it do me? It seems as though I haven’t anything to live for.” Then, remarkably, Jerry rallied and came home from the hospital early in December. Her progress toward health accelerated week by week during Ernie’s stay in Albuquerque. When he went to Hollywood on his way to the Pacific, Jerry accompanied him. One evening they went nightclubbing and danced for the first time in years.

‘I dread going back…’

It was with profound misgivings that Ernie set off again to war. “I dread going back and I’d give anything if I didn’t have to go,” he said. “But I feel I have no choice. I’ve been with it so long I feel a responsibility, a sense of duty toward the soldiers. I’ve become their mouthpiece, the only one they have. And they look to me. I don’t put myself above other correspondents. Plenty of them work harder and write better than I do, But I have in my column a device they haven’t got. So, I’ve got to go again. I’m trapped.” There was only one bright spot in Pyle’s contemplation of his new assignment. “Out in the Pacific,” he said, “I’ll be damned good and stinking hot. Oh boy!”

And so Ernie boarded a plane in San Francisco and headed for Hawaii, the Marianas and points west. Ultimately he will rejoin his Army G.I.’s in the Philippines or on some other embattled archipelago. But for a while now he will devote his special talents to the Navy. He was under a full head of steam last week, writing as fondly and luminously of “his” ship as ever he did of “his” company of doughfeet in Italy. “My carrier is a proud one,” he proclaimed. “She is known in the fleet as ‘The Iron Woman,’ because she has fought in every battle in the Pacific in the years 1944 and 1945.” Day by day his new friends became as vivid to Pyle readers as his old friends in foxholes beside the Rhine.

However long the war may last, Pyle is determined to cover it to the last shot. This resolution disturbs many of his admirers who regard Ernie Pyle as a nonexpendable national asset and who fear the mathematics of survival may now be against him. Although such an apprehension is not the prime element in his reluctance to return to war, he recognizes death as a disagreeable possibility. He is not afraid to die, but he looks forward very much to a day when he can jump into a car with unlimited gasoline and drive once again with Jerry by his side down the long white roads of the Southwest. “I can’t bear to think of not being here,” he says. “I like to be alive. I have a hell of a good time most of the time.”