LIFE (April 2, 1945)

America’s favorite war correspondent, now in the Pacific, is a diffident journalist who finds it hard to appreciate the importance of being Ernie

By Lincoln Barnett

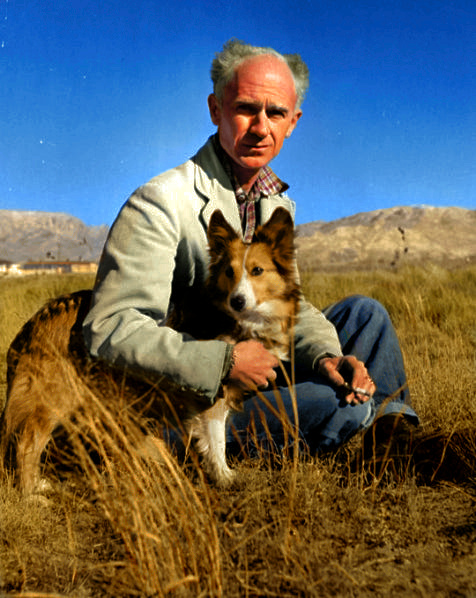

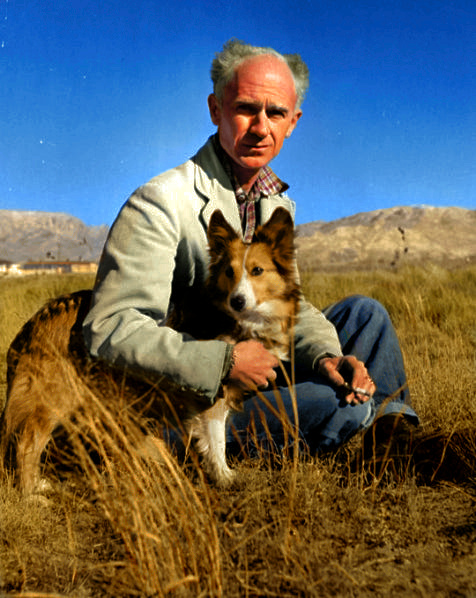

Ernie and his Shetland sheep dog Cheetah sun themselves on the mesa outside Albuquerque

“I got awful sick of Pyle this last year,” an ordinarily amiable gentleman remarked recently. “The whole country’s so intent on making him a god-darned little elf. I don’t understand it. How people can get all tied up in Pyle is beyond me.”

The speaker was Ernie Pyle’s oldest friend and college classmate, Paige Cavanaugh. His job at the moment is to make sure that The Story of G.I. Joe, a movie about the infantry as seen through Ernie’s eyes, does not overly glamorize its journalist hero. Cavanaugh is bored by the apotheosis of Pyle and has said so in writing. In a letter to Ernie, he announced, “I have completed my plans for the post-war world and I find no place in it for you.”

Certain differences between the public’s conception of Pyle and his own knowledge of the subject provide Cavanaugh with much tart amusement. By his articulate admirers Ernie has come to be envisaged as a frail old poet, a kind of St. Francis of Assisi wandering sadly among the foxholes, playing beautiful tunes on his typewriter. Actually he is neither elderly, little, saintly nor sad. He is 44 years old; stands 5 ft. 8 in. tall; weighs 112 lb.; and although he appears fragile, he is a tough, wiry man who gets along nicely without much food or sleep. His sense of humor, which leavens his columns with quaint chuckling passages, assumes a robust earthy color in conversation. His laugh is full-bellied. His profanity is strictly G.I. His belch is internationally renowned. “Ernie is the world’s champion belcher,” a friend once remarked enviously. “He doesn’t burp, he belches. It’s not a squashy, gurgly belch, but sharp and well-rounded, a clean bark with a follow-through. It explodes.”

Although Pyle is America’s No. 1 professional wanderer, he is fundamentally a sedentary person who likes nothing better than to sit in an overheated room with a few good friends. Unlike most writers he prefers listening to talking. Sometimes he appears to find conversation less pleasurable than the simple circumstance of being seated. When he visited Hollywood last fall, he holed up in Cavanaugh’s house and stayed there eight days without once visiting the studio where G.I. Joe was being filmed. His apparent agoraphobia is a byproduct neither of war nerves nor a swelled head. He has always been self-effacing and he finds himself uncomfortable in his current eminence as the nation’s favorite war reporter, Pulitzer Prize winner and author of two bestsellers. He has been called shy, but he is not timid. His reticence is marked by quiet dignity. He dreads crowds, however, and has avoided making speeches since an occasion during his college days when, addressing an undergraduate audience, he was struck dumb at the height of an eloquent period and fled the stage with one arm frozen in mid-air. He likes people as individuals and writes only nice things about those he mentions by name in his column. “But there are a lot of heels in the world,” he says. “I can’t like them.”

Pyle’s only breach of his self-imposed rule against speech-making occurred six weeks ago when he addressed an audience of 1,000 servicemen in San Francisco. The occasion was notable not only for his oratory, but for the fact that it signalized his departure, for the first time, for the Pacific theaters of war. Last week, from a carrier at sea, Ernie was writing enthusiastically of his experiences as a “saltwater doughboy.” Characteristically he had asked for assignment to a small carrier. “I felt I could get the feel of a carrier more quickly, could become more intimately a member of the family, if I were to go on a smaller one,” he explained. “Also, the smaller carriers have had very little credit and almost no glory, and I’ve always had a sort of yen for poor little ships that have been neglected.”

His inclination toward neglected little ships and neglected “little people” – though he would never employ such a patronizing term – is perhaps the most significant aspect of Pyle’s professional personality. As a roving columnist before the war, he wrote about barbers, bellhops, bartenders and bums. “Ernie avoids important people,” a friend once observed. “There’s only about one in every hundred he likes.” Actually Pyle is a democratic man who gets along as well with generals and admirals as with sailors and G.I.’s. But his individuality as a war correspondent has stemmed from his identification with the ranks, particularly combat infantrymen. He has written about fliers, engineers, artillerymen and tankmen. But he is first and foremost the apostle of the dogface who lives and dies most miserably. It was inevitable that he should have gravitated to the bottom of the military pyramid, for Pyle has always cherished the underdog. Seven years ago, after visiting the U.S. leper colony in the Hawaiian Islands, he made an illuminating confession, “I felt a kind of unrighteousness at being whole and ‘clean.’ I experienced an acute feeling of spiritual need to be no better off than the leper. It was something akin to that sorcery that lures people standing on high places to leap downward.” And so in war, Pyle has felt a spiritual need to be no better off than the coldest, wettest, unhappiest of all soldiers.

One result of Pyle’s dedication to the infantry is his current enshrinement in The Story of G.I. Joe. His connection with the picture originated when Producer Lester Cowan came to him for help in the summer of 1943. The War Department has asked Cowan to make a film about the unsung foot soldier. Pondering how to handle it, Cowan consulted the late Raymond Clapper who told him that Pyle was indisputably the infantry’s No. 1 exponent. After several meetings with Ernie, who was then in the U.S. on vacation, Cowan conceived the idea of integrating his narrative of G.I.’s in Tunisia and Italy around the character of Correspondent Pyle. Ernie agreed to cooperate but with three stipulations: 1) that the hero of the picture must be The Infantry and not Pyle; 2) that no attempt be made to glorify him; 3) that other correspondents be included in the story.

When the producer suggested that he act himself, Pyle retorted drily, “Okay, if you can get somebody who looks like me to write my column.” Public debate on the question, “Who should play Ernie Pyle?” reached an intensity second only to that generated seven years ago by the question “Who should play Scarlett O’Hara?” Thousands of fans wrote Cowan letters suggesting such assorted interpreters as Jimmy Gleason, Walter Huston, Bing Crosby and Jimmy Durante. From all over the country came photographs of balding skinny men who thought they looked like Ernie Pyle. One woman forwarded a snapshot of her balding, skinny husband with the comment, “Like Ernie, to know him is to love him.” Ultimately the contested part went to Capt. Burgess Meredith. The Story of G.I. Joe will have concurrent premieres for servicemen overseas in June and will be released to the civilian public in July. Producer Cowan, who is probably the nation’s No. 1 Pyle fan, is already planning a series of sequels which may ultimately make Ernie the Andy Hardy of World War II.

‘Mr. Pyle doesn’t want to get somewhere’

Although most professional achievements grow out of assiduity and ambition, Pyle paradoxically owes his unwelcome fame and now substantial fortune to his lack of ambition. His wife once astonished a well-meaning friend who wished Ernie to meet certain people who could help him “get somewhere” by proclaiming, “But Mr. Pyle doesn’t want to get somewhere.” The fact that Ernie has reluctantly pursued an uninterrupted course to professional success affords him and Cavanaugh a source of material for badinage. Their friendship developed originally out of mutual regard for each other’s pleasant inertia. But unlike Ernie, Cavanaugh has succeeded in happily drifting from one small job to another without ever making much money. One night last fall, during Pyle’s visit to Hollywood, Cavanaugh heard him sighing and tossing in his bed. “What’s the matter?” Cavanaugh called. “I can’t sleep,” Ernie replied. “That’s because you’re so damn rich,” said Cavanaugh. A little later Pyle heard Cavanaugh flopping around. “Now what’s the matter with you?” he asked. “I can’t sleep either,” Cavanaugh said. “That,” said Ernie, “is because you’re so damn poor.” Cavanaugh laughed, then remarked thoughtfully, “I got an idea. You give me half of your dough and then we can both get to sleep.”

The impact of fame has simply accentuated Pyle’s inherent modesty. During the weeks between his return from Europe last fall and his departure for the Pacific, he could have exploited his reputation in many ways. A radio network offered him $3,000 a week for the privilege of broadcasting transcriptions of his columns. A lecture impresario bid thousands for a personal tour. But money plays no part in Pyle’s mental processes. “What’s $100,000?” he once asked. “How much is that?” For years he refused to tell Cavanaugh the size of his income. “Now,” says Cavanaugh, “we’re square because Pyle doesn’t know how much he makes himself.” His book Here Is Your War has sold 942,000 copies and more editions are forthcoming. Brave Men had sold 861,000 as of February 1. His column is bought by 366 daily papers and 310 weeklies. All in all, his income during the last two years has probably been close to half a million.

He has no feeling for luxury

For all his riches Pyle owns only one suit. Landing in New York last fall with no clothes but his battle-stained uniform, he headed for a cut-rate store near his hotel and bought a suit for $41.16. It was still his only civilian garment when he left for the Pacific six weeks ago. Pyle simply has no feeling for luxury. His little white clapboard house in Albuquerque looks like any FHA model and cost about $5,000. Twice during recent months, it was so overrun with guests he had to surrender his bed. One night he slept on a cot in a shed behind the house. The other time he spread his new Army bedroll on the living-room floor. Although most of the time he doesn’t care whether he eats or not, he likes to cook for guests. He has no fancy tastes in liquor and likes to roll his own cigarettes. His friends often ask him what he does with his money. He doesn’t mind telling them: he puts it in war bonds. He never mentions the fact that he also quietly bestows substantial sums upon friends, relatives, G.I.’s and anybody else he likes.

Although Pyle disdains his affluence, he is keenly appreciative of the aureole of national esteem and affection that now envelops him. Somebody has said, “This war has produced two things – the jeep and Ernie Pyle.” His collated columns have been called “The War and Peace of World War II.” He is regarded in Washington as a kind of oracle. Congressmen and senators quote his words more often than those of any other journalist – and act upon them. Upon his return from Europe more than 50 high-ranking officers flocked to interrogate him at the Pentagon. However, Pyle has steadfastly refused to set himself up as a public thinker. He has rejected all offers to hold forth on the state of the nation, the Army or the world. And he has avoided politics. He didn’t even vote in the last election, explaining that he had lived so many years in Washington he had lost the voting habit. When friends asked him if he liked Roosevelt, he said “Sure.” He also said “Sure” when people asked him if he liked Dewey.

The emotions Pyle evokes in his public go beyond detached admiration. He is probably the only newspaper columnist for whom any notable proportion of readers have fervently prayed. The volume of prayer put forth for him each night can only be estimated by the hundreds of letters he receives from mothers and wives who declare they include him in their bedtime supplications. For some time after D-Day, 90 percent of all reader queries that came into Scripps-Howard offices were: “Did Ernie get in safe?” The bond between Ernie and his readers is strengthened by the fact that he takes time to write personal letters to hundreds of G.I. friends and to their parents and wives. Sometimes he goes to great trouble in behalf of utter strangers. On his homecoming voyage last fall, he met a wounded soldier who was particularly distraught because he could not summon courage to notify his parents he had lost a leg. “Are you trying to tell me you would like me to write that to them?” Pyle asked. That evening he sat down and composed a warm and friendly letter with all the care and craftsmanship he would have devoted to a column.

A fellow newspaperman who has affectionately followed Pyle’s career observed recently that when his big chance came, he was ready for it, thanks not to ambition but to 20 years of journalistic training. He might never have acquired that training had it not been for his physical indolence and a chance meeting with Cavanaugh in his freshman year at college. As a boy growing up on his father’s farm near Dana, Indiana (pop. 850), Ernie had come to dislike agricultural chores. He was a quiet lad who liked to sit and listen to his elders talk. In school he got high marks in English and geography and 100 percent in deportment. By the time he was ready for the University of Indiana, he knew that farming was not for him, but he had no idea what he did want to do. On registration day at the university in the fall of 1919, freshman Cavanaugh spied freshman Pyle idly rolling a cigarette and paused to borrow the makings. “What courses you taking?” Pyle asked. “They tell me,” said Cavanaugh, “that journalism is a breeze.” Together they walked to the journalism building and confronted a professor at the enrollment desk. They stood awkwardly, shifting from one foot to the other, a pair of self-conscious farm boys who didn’t know what to say. It was Pyle who finally spoke. “We aspire to be journalists,” he said.

Ernie just laughed and said, ‘We’ll see.’

For three and a half years Ernie fidgeted in class, cut lectures and did just enough work to get by. He was manager of the football team in his senior year and editor of the campus newspaper. But he had itchy feet and often vanished on solitary walks in the country. A few months before graduation he suddenly quit college and went to work as a reporter on the La Porte, Indiana, Herald-Argus. Cavanaugh tried to discourage him, pointing out that he “wouldn’t amount to much without his diploma” and that a degree would help him get jobs in future years. Ernie just laughed and said, “We’ll see.”

The next 12 years carried Pyle fortuitously, often unwillingly, to the springboard of his success. After four months in La Porte, he landed a job on the copy desk of the Washington News. He was an excellent headline writer but so mousey-mild his associates never dreamed he would ever be more than a pencil slave on the rim of the desk. Two years after coming to Washington, he married Geraldine Siebolds, an attractive and intellectual blonde girl from Minnesota who had a job with the Civil Service Commission. Each evening after work Ernie would sit contentedly at home, rolling cigarettes, chatting with Jerry, or reading. He became telegraph editor of the News in 1928. His interest in airplanes tempted him to essay an aviation column which soon became a popular feature of the News.

Of several circumstances responsible for the evolution of the peripatetic Pyle, perhaps the most important was his appointment as managing editor of the News in 1932. “I hated the damn job,” he says now, “though I think I did pretty good at it.” His restlessness came to the surface after he had fretted as managing editor for three years. In the spring of 1935, while convalescing from influenza, he took a leave of absence and motored through the Southwest with Jerry. On his return he looked with distaste at the dingy newsroom where he had spent most of his waking hours since 1923 and realized he was fed up with editorial labor. He asked for an assignment as roving reporter and to prove his point wrote some sample pieces about his trip. “They had a sort of Mark Twain quality and they knocked my eyes right out,” the Scripps-Howard editor in chief declared afterward. Pyle got his wish. His salary was raised from $95 to $100 a week and on August 8, 1935, his first travel column appeared in Scripps-Howard papers.

For the next five years, Pyle roamed the Western Hemisphere. He saw most of South America and once surveyed the shores of the Bering Sea. Nobody told him where to go. He wrote about the “long sad wind” that blows in Iowa and about a toothless Alaskan woodsman who made a dental plate out of bear’s teeth and then ate the bear with its own teeth. He wrote about his father (“He is a good man without being repulsive about it”), and about acquiring a new automobile (“Goodbye to you my little old car. In a few minutes I must go and drive you away for the last time. Trading you off for a shiny new hussy. I feel like a dog”). From the quaint introspective essays that recurrently appeared among his travelogs and interviews, his readers came to regard Ernie Pyle as an old friend whose tastes and vicissitudes they vicariously shared. They knew of his difficulties with zipper pants and his periodic illnesses. “If I’m going to be sick all the time,” he wrote once, “I might as well drop all outside interests and devote my career to being sick. Maybe in time I could become the sickest man in America.” With Ernie on his wanderings went Jerry, whom he puckishly referred to as “that girl who rides beside me.” Those itinerant pre-war years were the happiest of Pyle’s life. “The job would be wonderful,” he once said, “if it weren’t for having to write the damned column.” Meanwhile he was evolving his special reportorial capacities and style. When war came, he had no need to revise his technique. His farmers, lumberjacks and bartenders had become privates, sergeants and lieutenants. And Phoenix, Des Moines and Main Street were Palermo, Naples and the Rue Michelet.

‘I just cover the backwash of the war’

“A small voice came in the night and said ‘Go,’” Ernie wrote in the fall of 1940. It was the same voice that had spoken to him in the leper colony in Hawaii. So, he went off to war. Before his departure he bought a little white house in Albuquerque where Jerry could await his return. Till then the Pyles had never owned a home. They had lived for five years in hotel rooms. Now they needed a base – “not a permanent hearthside at all,” he explained, “but a sort of home plate that we can run to on occasion, and then run away from again.” Both Midwesterners, the Pyles had come to love the Southwest. They picked a spot on high ground overlooking miles of tawny mesa. “We like it,” Ernie wrote, “because our front yard stretches as far as you can see.”

Pyle’s first overseas trip in the winter of 1940-41 multiplied readers of his column by 50 percent. Stirred by the spiritual holocaust of London and his own relentless instinct for self-immolation, he produced columns of great beauty and power. But it was not till he reached North Africa the following year that the Pyle legend began to evolve. Despite the success of his British columns, he felt out of place at first among the crack war correspondents who had seen combat in China, Spain, France and Norway. And indeed, many of them regarded him patronizingly as a kind of travelog writer who had somehow obtruded on the war. When Pyle’s ship docked at Oran with the second “wave” of correspondents a fortnight after the initial landings, most of his fellow pressmen hurried eastward toward the front as fast as they could. But Ernie puttered around Oran. Then he caught cold. It was nearly Christmas by the time he reached Allied headquarters in Algiers. “Didn’t you go nuts, stuck back there in Oran?” a friend asked him. “Oh no,” said Ernie. “You guys go after the big stories. I just cover the backwash of the war.” Actually at that moment his columns were being excitedly discussed all over the United States. For while puttering in Oran he had met some obscure civilians who told him about the turbulent political situation in North Africa and he had dispatched some revealing articles criticizing the U.S. policy of “soft-gloving snakes in our midst.” The strict censorship at Algiers would never have cleared them for publication. But the Oran censors, perhaps disarmed by Pyle’s unpretentious reportorial style, let them go through. Not till weeks later did he learn he had inadvertently scooped the slickest newshawks in the world.

Pyle still thought he was covering the “backwash” of the war one morning in January 1943 when he boarded a plane at an airport outside Algiers and headed eastward toward the red eroded ridges of Tunisia. He still had no idea he was to become the patron saint of the fighting foot soldier. He only knew that grand strategy was not his racket. He knew how to move unobtrusively among men and chat with them quietly until they began to articulate their adventures and thoughts. He described the looks of the country and told how he lived. And in writing about himself he defined the soldier’s existence, for he lived no better than any G.I. He dressed like a G.I., in coveralls and a wool cap. He gained almost ten pounds on canned rations but lay awake night after night, quaking with cold, fully clothed inside his bedroll. He learned how to dig foxholes in a hurry. “It wasn’t long,” he wrote, “before I could put up my tent all by myself in the dark with a strong wind blowing and both hands tied behind my back.” And he learned that in cold weather it is more comfortable to go without baths. “The American soldier,” he once observed, “has a fundamental complex about bodily cleanliness which is considered all nonsense by us philosophers of the Great Unwashed, which includes Arabs, Sicilians and me.” Jeeping all over the Tunisian battle area, he got bombed and shelled and on one occasion found himself the sole target of a German machine gunner who sent several bursts in his direction “so close they had fuzz on them.” He left famous heroes to the headline reporters and confined his efforts to the brave but obscure. He made friends in every unit in North Africa. But he gravitated ineluctably to the infantry – “the mud-rain-frost-and-wind boys.”