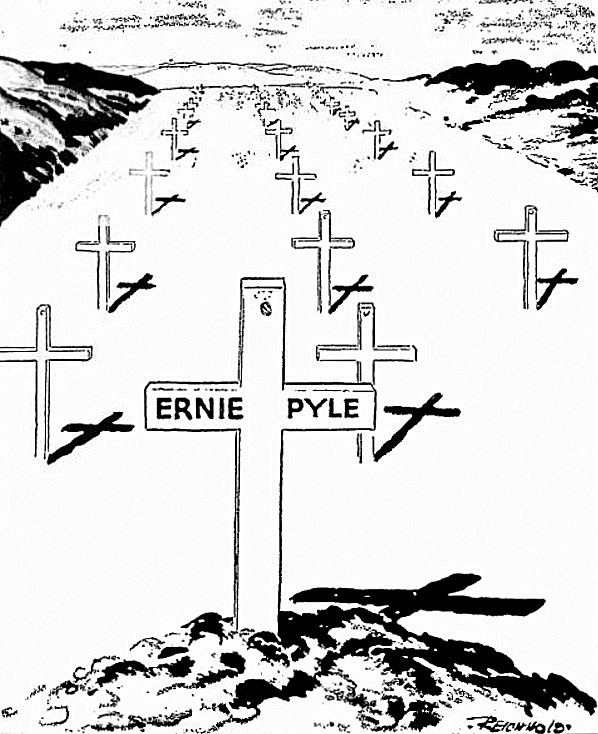

G.I.’s hardest hit by death of Pyle

Overseas veterans feel loss keenly

Wednesday, April 18, 1945

Ernie Pyle’s death was a shock to the nation, but it hit hardest the men wearing those overseas service ribbons.

Servicemen and civilians alike were shocked by the word of his passing today, but on Pittsburgh’s streets, in the USO canteen, in drug stores and in public buildings it was the man in uniform who felt the keenest loss.

Met him in Italy

Pvt. William McGonigal of Montgomery County sat in the Canteen and stared at the floor when he heard the news. Then he said:

I shook hands with him near the Volturno River in Italy. He wrote about our outfit making the crossing. He was the one correspondent everyone wanted to meet. There was something about him… always up there on the line with us…

Added Pvt. Keat P. Heefner of Mercersburg: “He was with my outfit in Normandy… He was tops. We looked forward to seeing what he wrote just as much as civilians did…”

WACs pay tribute

Near the Canteen, two WAC sergeants told how they felt:

“It’s the second tragedy in a week,” declared Sgt. Connie McKim, and her companion, Sgt. Mary Haumesser, added: “I always read his column. No one could have written better.”

Said Pvt. Kenneth Strouse of Lakeside, Ohio: “We all learned things about the Army from Ernie, things we never learned from the Army itself…”

“It’s just Ike losing another commander-in-chief,” asserted Pvt. John J. Kane, 711 Southern Avenue.

But it fell to Lt. E. M. Morgan, whose address here is the Downtown YMCA, to sum up the way the servicemen felt about Ernie Pyle: “He had a lot of guts.”

That was the reaction of Pittsburghers in high places and low as the news spread throughout the city and received a reaction of stunned disbelief.

G.I.’s lose spokesman

“The G.I.’s have lost their spokesman,” said Orphans Court Judge Alexander C. Tener. “His columns and books were unique literature of warfare. He was close to the heart of every loyal American.”

Attorney Oliver K. Eaton: “His death is one of the real tragedies of the war… There’ll never be another Ernie Pyle…”

Brought war into home

Director of Elections David Olbum: “He brought the war right into your kitchen…”

Frank Knox, police radio operator: “Through his columns I had a clear insight into the things my two boys are going through in Italy and Germany…”

Then there was “Richey,” the veteran “newsboy” at Liberty Avenue and Ferry Street, who was shocked at the news.

“It’s a tough blow to the readers who depended on Pyle,” he declared.

In Morals Court Magistrate W. H. K. McDiarmid declared Pyle’s death “a great shock to me, and a great loss to American journalism,” and Safety Director George E. A. Fairley added: “He was loved by the fighting men because he was not afraid to take the chances they took.”

‘National calamity’

“His passing is a national calamity. Ernie Pyle is just a household word. Everybody knows him,” said Collector of Interna! Revenue Stanley Granger, a veteran of the last war.

Another World War I veteran, Daniel Core, deputy clerk of U.S. Courts: “I think he gave us more insight into the life of a private soldier than any other correspondent has done.”

Weatherman William S. Brotzman, when told of Ernie Pyle’s death, exclaimed:

That’s a pity. He’s one of the best. He included so much in his stories – a good picture of the country, what the weather was like, what the boys were experiencing.

Knew trials best

Postmaster Stephen Bodkin said:

Ernie Pyle knew the problems and trials and tribulations of the doughboy perhaps better than any other person. I read him every day and read all his books. He was the war’s top-notch correspondent.

Judge Frank P. Patterson:

This dreadful war has brought us many tragedies, but none so personally shocking as the death of this fine reporter. He told the news as no other war correspondent did; he was a man who had the common touch. I, like everyone else, feel an overwhelming sense of loss in his passing.

“I think his loss will be felt deeply by the American public,” said Harry T. O’Connor, special agent in charge of the Pittsburgh office, FBI.