Reading Eagle (January 27, 1943)

Move to wean Axis satellites seen’ offensive from West is indicated

By Harrison Salisbury, United Press staff correspondent

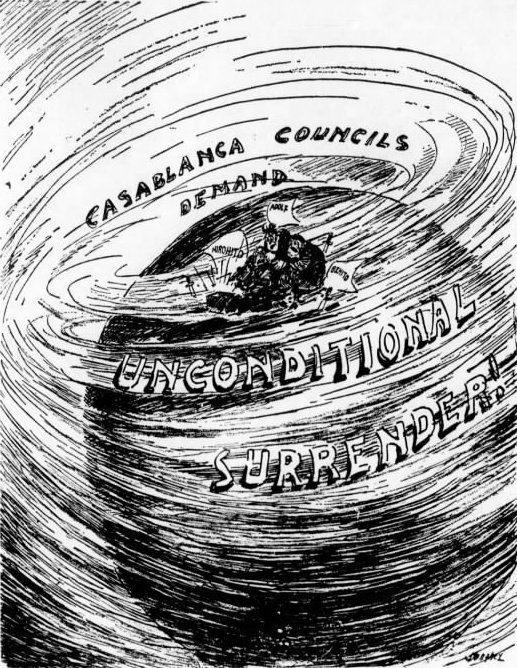

The world today heard the story of ten days at Casablanca in which President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill placed their stamp upon 1943 offensive plans to bring about the “unconditional surrender” of the Axis.

But indications grew that the dramatic announcement of the war conference on the sun-drenched African coast left many dramatic events and important decisions unrevealed.

Strategic decisions, it was certain, would not be revealed until their reality is brought home to the Axis by the crunch of bombs, the blast of shells and the scramble of landing troops on the European continent anywhere from Norway to Italy or the Balkans.

Maneuvers unrevealed

However, suggestions appeared in dispatches of United Press correspondents from North Africa that diplomatic maneuvers of unrevealed scope may have accompanied the military discussions.

There was no authoritative basis for these suggestions and there was no statement from Allied quarters touching on the possibility of moves designed to wean Axis satellites or sympathizers away from Adolf Hitler.

Finland was hinted as one possible subject of an Allied get-out-of-the-war-while-the-getting-is-good drive. Italy was another and there were rumors as to eye-opening and cards-on-the-table maneuvers involving Spain, Turkey and Sweden.

The ten-day session of the President and Prime Minister ending Sunday, overshadowed all other news from the far-flung fighting fronts of the war.

The news of fresh Russian successes, of deepening gloom in Germany’s satellite states, of ever grimmer warnings by Nazi propagandists to the German public of the seriousness of the reverses in the East provided a dramatic background for the Casablanca announcement.

Foremost in the conclusions drawn in Washington and London was a conviction that the big news of Casablanca is yet to be told.

Results of parley

Thus far, these results of the conference have been made known:

-

Allied strategic plans for 1943, calling for blows from the West against Hitler’s citadel timed to coincide most effectively with Russian blows from the East, have been started toward execution.

-

Specific details for the liquidation of the Axis foothold in Tunisia are presumably settled and should quickly be clarified with announcements of a new Anglo-American command in the Mediterranean.

-

The initial step toward bringing together the dissident French groups represented by Gen. Charles de Gaulle and Gen. Henri Honoré Giraud has been taken, but full collaboration and agreement is still distant.

-

No apparent progress toward establishment of a unified Allied high command, with Russia and China represented, appears to have been made. However, Joseph Stalin and Chiang Kai-shek were closely advised of Anglo-American decisions.

Some observers believed the language of the Casablanca communiqué, particularly in passages in which Mr. Roosevelt and Churchill appeared to speak for Stalin and Chiang Kai-shek as well as themselves

Confer in Moscow

Stalin and Foreign Minister V. M. Molotov met with British and American diplomatic representatives in Moscow last night a few hours before the news of the Casablanca meeting was flashed to the world.

The communiqué emphasized that Stalin had been invited to attend the conference, but that he found it impossible because of his preoccupation with the Red Army’s offensive.

London reaction to the announcement was enthusiastic except as regards the de Gaulle-Giraud situation. Fighting French spokesmen made clear that whatever progress had been made in settling this thorny issue was almost entirely confined to generalities. De Gaulle and Giraud, it appeared, agreed in their common desire to win France’s liberation and to fight for that end – but on little else.

However, the feeling was strong in London that much more has not been told about Casablanca than has been placed on the record.

This feeling was shared by correspondents in Africa. They noted there was no real necessity for Mr. Roosevelt to make a 6,000-mile trip by air to Africa simply to have a heart-to-heart talk with Churchill, that the joint Allied staff conferences could have been held much more conveniently elsewhere and that speculation and inquiries by newsmen as to participants in the discussions – other than those officially announced – were severely discouraged.

Multitude of rumors

They occupied these observations with the multitude of rumors suggesting that Finnish, Spanish, Turkish, Swedish or even Italian representatives may Have been there. There was no tangible evidence, apparently, for these rumors except Finnish labels spotted by one correspondent on the luggage of one of the arrivals at Casablanca.

There have been some reports recently suggesting that the Finns might be interested in a way out of the war. A Finnish mission headed by Commerce Minister V. A. Tanner is currently in Stockholm, and the German radio only last week claimed that Russia had made a new peace offer to Finland which was rejected. There appears to have been little fighting other than minor skirmishes on the Finnish-Russian front for nearly a year.

Finland’s positions would be of major strategic importance to the Allies in event of a move on northern Norway designed to clear the convoy route to Russia.

The revelation that Mr. Roosevelt and Churchill, accompanies by every top military, naval and air chieftain of the Anglo-American Command had met for 10 days on the African coast right under the nose of the Axis, was beamed to occupied and Nazi Europe by all available means.

The initial effect of the Casablanca Conference was expected to be felt in North Africa.

New army setup seen

While no immediate announcement was forthcoming, it was assumed that complete decisions on the Allied command and tactical plans for the elimination of remaining Axis forces there had been made.

London believed that two commands would be established – a commander-in-chief for the whole Mediterranean, presumably including any forthcoming operations from that theater against Europe, and a field commander in Africa itself. The African field commander would assume charge of the British 1st and 8th Armies and the U.S. 5th Army. London believed an American general would receive one post and a British commander the other. It appeared to be a tossup as to which would receive which.

Caution was voiced in London against expectations of an immediate Allied sweep through Tunisia or any immediate dramatic Allied move against the continent.