The Evening Star (September 1, 1946)

Nazis rant and plead for mercy in final appeals in Nuernberg

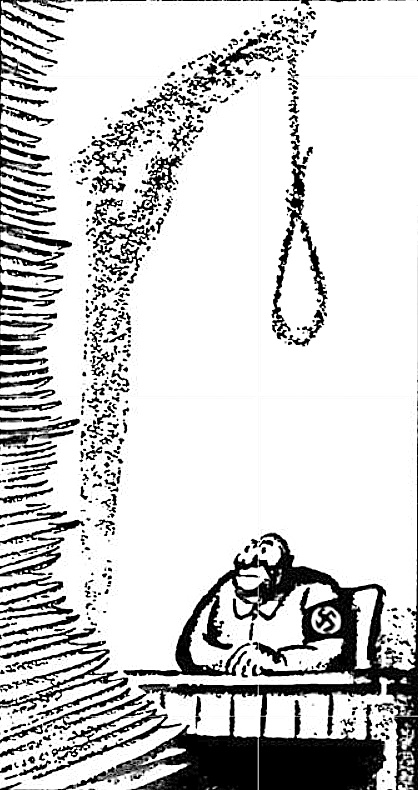

NUERNBERG, August 31 (AP) – Twenty-one henchmen of Adolph Hitler will learn their fate September 23, the International Military Tribunal announced today after hearing them rant defiantly or plead for mercy in their last gestures to escape the gallows.

Hollow-eyed Walther Funk, former Reichsbank head and economics minister, wept as he pleaded he did not know of Nazi crimes. But Reichsmarshal Hermann Goering shouted his innocence, asserting he was “standing back of everything I have done.”

These two were among the 12 who told their attorneys they expected death. Hjalmar Schacht, Constantin von Neurath and Franz von Papen expect clemency, the attorneys said, while Karl Doenitz, Erich Raeder, Alfred Jodl, Baldur von Schirach, Hans Fritzsche and Julius Streicher still hold out hope. Goering looked pleased as gaunt, ashen-faced Rudolf Hess, onetime deputy to Hitler, stormed and ranted and protested that some defendants acted “very strangely and made shameful utterances about the Fuehrer.” But for the most part Hess’ tirade was rambling bewildered and at times unintelligible.

Defense attorneys said 12 of the defendants expected to be hanged, three thought they would escape, and six still “have hopes.”

Some in their final statements turned savagely on Hitler, branding him the only real criminal; others reaffirmed belief in the Fuehrer. One wept. Some with bravado declared they were not afraid to die. Others professed ignorance of Nazi excesses, or pleaded “duty” to the state.

Some asked that even if they were not spared, the German people be acquitted so that Germany might again rise as a nation. The 21 tired and mostly frightened men used 30,000 words in final excuses for executing orders that brought misery or death to 25,000,000 persons. Their statements concluded a trial which began November 20, 1945, before British, French, Russian and American judges constituting the first International Military Tribunal in history.

When the parade of 21 defendants – Deputy Fuehrer Martin Bormann, the 22nd, was tried in absentia – finished their statements, Lord Justice Geoffrey Lawrence, announced an immediate recess until 10 a.m. September 23, when the judges will announce their verdicts. The tribunal’s word is final, but will be subject to review of the Allied control authority in Berlin.

Justice Lawrence praised counsel for both the prosecution and the defense. He said some Germans had written to German defense counsel protesting defense lawyers’ conduct, and added that the attorneys would be given the protection both of the tribunal and the Allied Control Council.

Goering protests innocence

Each defendant had been allotted 10 minutes to make the final statement. Only Hess ran overtime.

Goering, his sharp, peering eyes averted from the tribunal, contended the prosecution failed to show he could have known “everything that happened under Hitler.” Protesting his innocence, he declared he never decreed “the murder of a single individual.”

“The only motive which guided me was my ardent love for my people,” the Reichsmarshal, now thin and wan, declared. “I call on the Almighty and the German people as my witness.”

Hess, who flew to England during the war in a futile attempt to arrange a German-dictated peace, remained seated as he spoke, pleading ill health. He unleashed a storm of abuse against some co-defendants and attacked the whole court procedure. As he talked, Goering laughed and made penciled notes.

Hess rambled for a full half hour, until the court lost patience. He devoted much time to his flight to Britain. “There,” he said, “people surrounded me from time to time. They changed from time to time. They had glassy eyes – dreamy eyes. Then they changed and gave the impression of sanity. In the spring of 1942 I had a visitor, quite obviously nice to me. He had strange eyes with a dreamy cast.”

Hess no longer read from notes, and the presiding justice lost patience. Hess was warned, but he rambled on about his duty as a “faithful follower of my Fuehrer,” stating he would act the same “if I had the same opportunity, even if I knew I would meet death in a bonfire.”

Recalls Stalin meeting

Joachim von Ribbentrop, champagne salesman who became German foreign minister, declared the only respect in which he considered himself guilty was “that my foreign political wishes did not meet with success.” Pale and lacking his former suavity, Von Ribbentrop said he sought only what the other nations did.

“In 1939 I met Stalin in Moscow and he didn’t seek peaceful settlement,” he said. “The conduct of the man in 1939 was not considered a crime against peace.”

Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, chief of the German high command, blamed Hitler as the real instigator of the army’s orders, but said he “acted according to my duty as I saw it.” Ignoring attempts by Hess to heckle him, Keitel said:

“I claim to have told the truth in all things, even if they incriminate me.”

Keitel declared the German Army should have had less discipline, implying that relaxation of the traditional Prussian attitude would have allowed the generals to refuse Hitler’s bidding.

Ernst Kaltenbrunner, former chief of the dread Nazi Sicherheitsdienst, the Security Police, pleaded he knew nothing about the anti-Semitic excesses of the Nazis, which he admitted were barbaric. He said his conscience was clear.

Alfred Rosenberg, one-time philosopher of Nazism, cast the blame on Hitler for drawing about him people “who were not my comrades but my enemies.”

Frank accuses Hitler

Hans Frank, governor general of Poland who was known as the “butcher of Warsaw,” bitterly accused Hitler as the "main defendant,” berated Hitler’s suicide as “cowardice,” and said Germany lost the war because “God had spoken his judgement over Hitler.” He said he had heard crimes “committed by the Russians and Poles and Czechs” since the war’s end and these “more than balance the crimes Germany is charged with.”

Wilhelm Frick, former interior minister, said he was only a civil servant and had a “clear conscience.”

Streicher, anti-Semitic publisher, defended himself against the charge of being the No. 1 Jew-baiter, saying the prosecution failed to prove his writings influenced Hitler’s extermination policy.

Schacht, finance wizard and former Reichsbank president, said he had broken with Hitler, and his feelings of justice were “deeply wounded” because he was ranked as a conspirator.

Doenitz, who became Germany’s Fuehrer in the last days of the war, said German naval warfare was conducted legally and he would do it the same way all over again. He said the Fuehrer principle worked well in military matters and that he thought, mistakenly, it would work also in politics.

Raeder, commander-in-chief of Nazi submarine warfare, said he had done his duty as a soldier and “I am prepared to die at any moment.”

Von Schirach, Hitler youth leader, castigated Hitler and pleaded for the Hitler Jugend.

Fritz Sauckel, Nazi boss of foreign labor, admitted he was “shaken by the atrocities revealed” at the trial, and said his great veneration for Hitler had been his chief error.

Jodl, chief of the German General Staff, said he and his army generals had the task “of conducting a war they did not want under a chief who did not trust them.”

Von Papen finds no guilt

Dapper diplomat Von Papen said that “when I examine my conscience, I cannot find any guilt where the prosecution sought to place it.”

Von Neurath, former protector of Czechoslovakia, said he had a “clean conscience,” and that if the verdict were guilty, “I will bear even this and take it upon myself as a last sacrifice to my people.”

Arthur Seyss-Inquart, Nazi commissioner for Austria and the Netherlands, said he remained loyal to Hitler “who made a greater Germany a fact in German history. He added that “today I cannot crucify him to whom yesterday I cried Hosannah.”

Albert Speer, Nazi production minister, said after this trial the German people would condemn Hitler and dictatorships based on fear. He referred to atomic weapons and warned against future wars.

Fritzsche, deputy propaganda minister, displayed the best spirits of all the defendants. However, his guards reported that he spends much of his time in his cell weeping.

All 21 are found sane

War Department psychiatric tests of the 21 Nazis have pronounced all of them sane, it was learned. But the rambling final statement of Hess once again raised doubts about him.

Lt. Col. Robert N. Dunn, a professional psychiatrist, spent three weeks in the Nuernberg prison observing the defendants, and now is on his way back to Washington with his findings. His report will say, it was learned, that the tests showed each defendant was fully aware of his actions during the Nazi regime. Some were found to have psychopathic reactions, the report will say, but that did not mean they were insane.

American officers were interested particularly in the mental makeup of such hard-bitten militarists as Keitel, Jodl, Doenitz and Raeder.

The psychiatrist’s report listed Hess as sane at the time he examined him. But Hess put up a show as somewhat of a lunatic with his final speech today, much of it devoted to a discussion of the “dreamy, glassy eyes” which surrounded him during his captivity in England.