The Pittsburgh Press (November 20, 1945)

‘HITLER GANG’ ON TRIAL

Four-power tribunal sits at Nuernberg

Two of defendants tried in absentia

By Frederick C. Oechsner, United Press staff writer

NUERNBERG (UP) – Twenty-four fallen leaders of the Nazi regime went on trial before a United Nations tribunal today and listened uneasily to a shocking indictment holding them directly responsible for the death and misery of World War II.

The trial that for the first time in history sought to prove aggressive warfare a crime against all mankind opened in an atmosphere of grim, cold legality in Nuernberg’s ancient Palace of Justice.

Twenty-two men were on trial, all top figures in the Nazi hierarchy that overawed Europe for a decade. But two were being judged in absentia – the ailing Ernst Kaltenbrunner and the missing Martin Bormann.

Reads indictment

Sidney S. Alderman of Washington, of the American prosecuting staff, began the reading of the 25,000-word indictment shortly after the hearings opened at 10:03 a.m. (4:03 a.m. ET).

He spoke slowly and deliberately as he read off the first of the four principal accounts in the indictment – that charging the accused men of plunging the world into war.

He was followed to the dais by members of the British, French and Russian prosecution staffs, who intoned the succeeding passages of the indictment for the benefit of the four presiding justices and the jittery defendants.

Prepare motion

After the reading of the lengthy indictment and three appendices detailing the charges, the court adjourned.

Defense lawyers for the accused Nazis, acting as a committee, prepared a motion for presentation today, protesting the charge of violation of international law.

The defense motion charges that international law did not exist at the time of the alleged crimes.

The defendants themselves appeared to be the most interested men in the courtroom. They followed the reading of the indictment with rapt attention over their earphones attached to their bench.

Hermann Goering, the No. 1 defendant, twisted uneasily in his front row seat. From time to time, he leaned over to whisper something to his bench mate, Rudolf Hess, and occasionally an inane grin twitched across his fat face.

Sit near Goering

He nodded several times as Mr. Alderman traced the illegal development of the German Air Force under his direction in the pre-Munich days when Nazi Germany was secretly arming for war against the world.

The Russian prosecutors sat almost within arms’ reach of Goering, but they ignored him studiously.

The yellow-faced Hess beside him was more impassive throughout, clinging stubbornly to his claim that he remembered nothing of the Hitler era in which he played so large a part.

He spoke occasionally to Goering and Joachim von Ribbentrop. But for the most part he maintained an air of cold aloofness from his fellow Nazis and his judges alike.

Hess stared grimly at the wall when the indictment enumerated the mass murders carried out by the Nazis in their bid for mastery of Europe. Goering’s eyes dropped to the floor, and Franz von Papen merely cupped his chin in his hand in an academic manner as if he personally were not involved.

Laughs derisively

Hjalmar Schacht, branded as the financial brains behind the Hitler facade, laughed derisively when the French prosecutor read off that section of the indictment dealing with the murders and mass deportations.

Julius Streicher leaned forward in his seat one hand on his hip and surveyed the courtroom arrogantly.

The accused men took a lively interest in the proceedings, craning their necks to inspect each new arrival, fiddling with the translating devices on their chairs, and conferring animatedly with their counsel.

Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, Col. Gen. Alfred Gustav Jodl and Ribbentrop engaged in heated conversation as the afternoon session got underway. They appeared to be angry about something. Schacht listened to them with a detached air and Hess stared vacantly into space.

The trial was opened formally by the four presiding justices: Francis J. Biddle, American; Sir Geoffrey Lawrence, British; Maj. Gen. Iona T. Nikitchenko, Russian, and Henri Donnedieu de Vabres, French.

Outlines purposes

Mr. Lawrence outlined the purposes of the tribunal and recited the history of this precedent-making case that for the first time in human annals establishes aggressive war as a crime against humanity.

“The tribunal has heard with satisfaction the steps taken by the prosecution to aid defense counsel make possible a just defense,” Mr. Lawrence said.

“This trial is unique in the judicial history of the world. It is a solemn responsibility of all involved to discharge their duties without fear or favor.”

He reminded the crowded room that he would insist on order at all times.

Then the British justice ordered the indictment to be read.

Three of the original 24 defendants were missing from the trial through suicide or sickness.

A fourth, former deputy Nazi Party Leader Bormann, was being tried in absentia, despite the partially confirmed belief that he died with his master, Adolf Hitler, in the ruins of Berlin.

To plead madness

Two others, the beetle-browed Hess and the viciously anti-Semitic Streicher, apparently hoped to escape the scaffold by pleading madness. Their plea was expected to be ruled on immediately after the court opening.

The accused were hustled under heavy guard from their cells in the Nuernberg prison across the street and up into the flood-lit trial room in a specially built private elevator.

Each man bore a prominent identifying number across his chest.

The indictment demanded death for all of the accused on four principal counts:

-

That they took part in a general conspiracy which involved crimes against peace, war crimes and crimes against humanity.

-

That the defendants and many other Nazi leaders now dead or hiding led the German nation into a war of aggression in violation of Germany’s treaty obligations.

-

That they committed war crimes directly or indirectly.

-

That they directly committed crimes against humanity.

To rule on pleas

The judges were to rule on Hess’ insanity plea; a motion for a mental examination of Streicher; the Franco-Russian request for trial of Alfried Krupp in place of his aged and ailing father Gustav, and the status of Kaltenbrunner, who suffered a hemorrhage in his cell Sunday night.

Physicians believed it would be at least three weeks before Kaltenbrunner could appear in court, and it was expected that the trial would go ahead without him until that time.

Gustav Krupp was regarded as too sick ever to stand trial for his role in the building of Nazi Germany’s war machine. But all four prosecutors appeared to be in agreement on trying his son, Alfried, at a later date, along with a group of other German industrialists.

Who’s who among defendants

NUERNBERG (UP) – Here is the list of defendants in the Nuernberg war guilt trial:

- Martin Bormann, one-time No. 2 Nazi, in absentia (may be dead)

- Grand Adm. Karl Doenitz

- Dr. Hans Frank, Nazi ruler of Poland

- Dr. Wilhelm Frick, “protector” of Bohemia and Moravia

- Hans Fritzsche, editor and propagandist

- Dr. Walther Funk, economics specialist and Reichsbank head

- Reichsmarshal Hermann Goering

- Rudolf Hess, once Hitler’s heir-apparent

- Col. Gen. Alfred Gustav Jodl, chief of staff of the German Army

- Lt. Gen. Ernst Kaltenbrunner, chief of the Nazi Security Police (who suffered a slight brain hemorrhage on the eve of the trial)

- Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel

- Constantin von Neurath, former foreign minister

- Franz von Papen, top Nazi diplomat and World War I spy

- Grand Adm. Erich Raeder

- Joachim von Ribbentrop, Nazi foreign minister

- Dr. Alfred Rosenberg, ideological leader

- Fritz Sauckel, SS and SA general

- Dr. Hjalmar Schacht, Nazi fiscal wizard

- Baldur von Schirach, Nazi youth leader

- Dr. Albert Speer, Nazi armaments director

- Julius Streicher, Jew-baiter

The Evening Star (November 20, 1945)

War trial opens at Nuernberg with 22 Nazis as defendants; indictment reading takes day

Arraignment is due tomorrow; Hess is present in court

By Daniel De Luce, Associated Press foreign correspondent

NUERNBERG (AP) – A score of gloomy Nazis sat dejectedly today before the International War Crimes Tribunal and heard themselves formally accused of Nazi war crimes, the murder of 10,000,000 Europeans, plunder, horror and torture.

Throughout the opening session of the trial for their lives, 20 Hitlerian followers, such as corpulent Hermann Goering, vague Rudolf Hess and defiant Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, listened through earphones while spokesmen of the nations which crushed their hierarchy recited crimes the world had never before witnessed. An impish grin played around Hess’ sunken mouth.

By turns prosecutors of the United States, Great Britain, France and Russia droned through the four counts of the 35,000-word indictment accusing the last of the leading Nazis of conspiracy to commit crimes against peace, actual commission of crimes against peace, war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Although only 20 Nazis were present, two others – Martin Bormann, Hitler’s deputy, who is being tried in absentia, and Ernst Kaltenbrunner, who suffered a brain hemorrhage Sunday night – are defendants.

The only ones of the original 24 Nazis now missing from the list of defendants are Robert Ley, Labor Front boss, who committed suicide, and Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, former head of the great German armaments firm, who is suffering from softening of the brain and whom the court has removed from the indictment.

Charges against Kaltenbrunner were read, despite his absence, in the hospital. He was nearing the end of the critical period of his illness tonight, and doctors said he would be hospitalized for a month. The court must decide whether Kaltenbrunner will be tried in absentia or reindicted for later trial.

Arraignment tomorrow

Even the appendices containing individual charges against the 22 defendants were read, meaning that the men who terrorized Europe only a year ago could not be arraigned until tomorrow. Opening statements by the prosecution will follow.

The Nazis sometimes sat with earphones clasped on to hear translations in German piped to them as the prosecutors read in English, French and Russian. Robed attorneys sat beside them.

What disposition the tribunal would make of the reports of alienists on Hess’ mental condition had yet to be announced. But the former Hitler deputy seemed at moments almost frivolous as the proceedings got underway.

The black-gowned defense attorneys listened intently to every word that was spoken, but their clients, as strangely garbed as a cast of beggars in an opera, exhibited varying emotions.

Deeds of Reich recounted

The Nazi defendants were dressed in simple uniforms without medals or insignia of rank or in simple civilian suits donated from charity stores.

The defendants listened as lurid deed after lurid deed of the Third Reich was reconstructed in English.

British Lord Justice Geoffrey Lawrence, presiding, told the defendants that Britain, the United States, the Soviet Union and France had been entrusted with the punishment of war criminals, adding: “This trial which is about to begin is unique in the history of jurisprudence and in importance to people all over the world.”

Justice Lawrence then ordered the reading of the indictment.

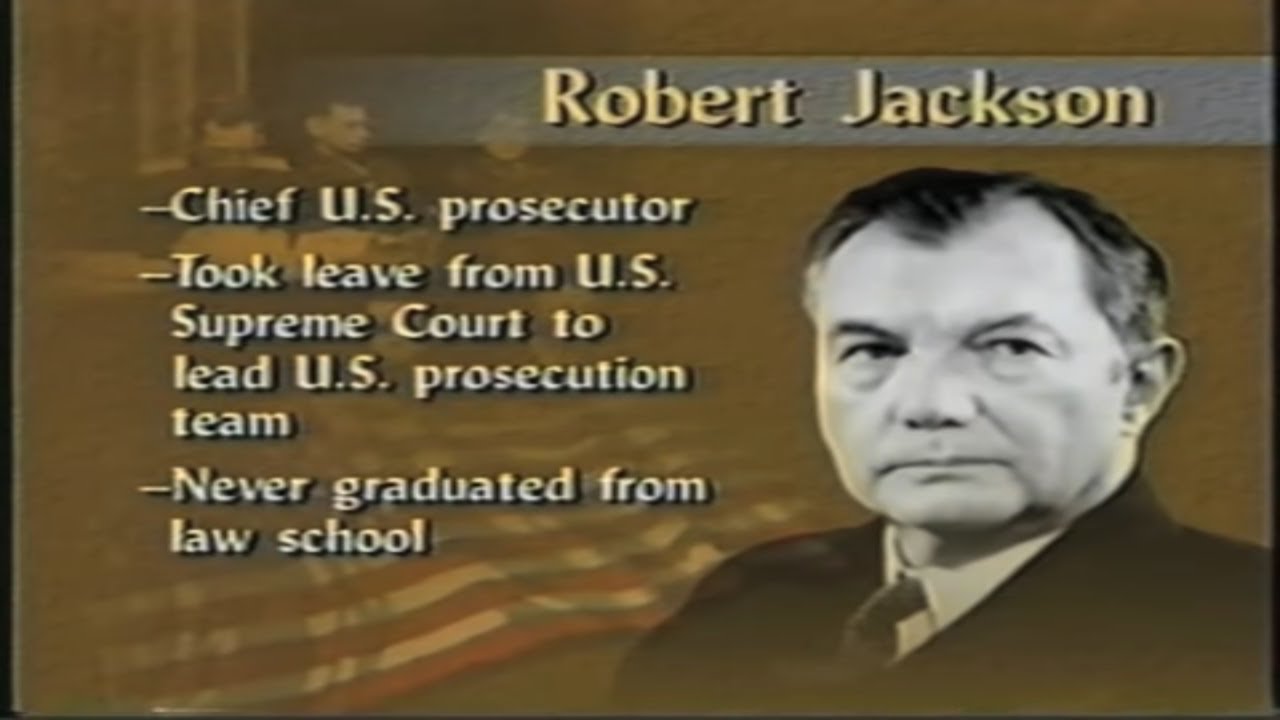

Sidney S. Alderman, assistant to the chief American prosecutor, Justice Robert H. Jackson, opened the proceedings by reading a condensed version. His voice trembled with nervousness.

The defendants stared during the lengthy reading. Hess, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Keitel and Alfred Rosenberg listened without using the translators’ earphones provided for each man on trial.

Goering, his fat countenance exhibiting bored composure, soon removed his headphones. Grand Adm. Erich Raeder and Walther Funk, former Reichsbank president, continued to use the American translating device.

The prosecution tables were crowded. Justice Jackson sat at the head of the United States delegation. Sir David Maxwell-Fyfe headed Britain’s delegation while Col. Yuri Pokrovsky and Charles Dubost were sitting as temporary chief prosecutors for Russia and France.

At Mr. Alderman’s mention of anti-Jewish fulminations during the pre-war period by Rosenberg, that defendant hurriedly replaced his earphones. Julius Streicher, No. 1 Nazi Jew baiter, sat bolt upright when he was named in the indictment.

Goering nodded with emphasis when the prosecutor recalled his announcement of 10 years ago that Germany was building a military air force.

Finish of first count

Mr. Alderman concluded the reading of the first count of the indictment with these words:

“The defendants with divers other persons are guilty of a common plan of conspiracy for accomplishment of crimes against peace – against humanity – war crimes not only against armed forces of their enemies but also against nonbelligerent civilian populations.”

After the British prosecutor read the five paragraphs of count 2 – titled “Crimes Against Peace” – the court recessed for 15 minutes.

Through the reading of the counts, Arthur Seyss-Inquart, Hitler’s trigger man in the 1938 seizure of Austria, stared blankly through thick lensed spectacles as his role in the Nazi pre-war scheming for power was unfolded.

A German attorney disclosed that Goering’s counsel, on behalf of the entire defense group, intended to offer a joint declaration challenging the jurisdiction of the international court. This was expected after the indictment reading was completed and the defendants had entered pleas.

Goering persisted in outgesturing his Nazi cronies and in retaining the courtroom’s interest. He leaned forward to kibitz over the shoulder of a German lawyer.

When Dubost started reading the third count of the marathon indictment, the former reichsmarshal was having trouble with his earphones. Finally he took them off and leaned forward, hand in chin, while the Frenchman droned on, reading the long atrocity count.

The rest of the defendants merely looked bored.

Hess, toward the end of the morning session, started a long and animated conversation with Ribbentrop. Goering, sitting next to them, ignored both.

The defendants exhibited their greatest solemnity while a portion of the indictment was read describing the murder of millions of Nazi victims in Europe.

Even Hans Frank, whom the Poles called “the Butcher” while he was ruling their land, sat with his chin resting on his chest and with his earphones clasped to his ears. Earlier, he had smiled frequently while gazing around the courtroom.

Among those attending the opening session were Lt. Gen. Lucian K. Truscott, commander of the Third Army, and Sen. Claude Pepper (D-Florida).

Goering’s appetite keen

During the recess for lunch, the defendants remained in the court and ate heartily from American Army mess kits. Goering’s appetite was particularly keen.

When the court was cleared, the Nazis leaped up and began shaking hands with each other enthusiastically. Though many had occupied adjoining cells for months, solitary confinement had restricted their conversations and many were able to exchange words for the first time since reaching Nuernberg.

Dr. Hjalmar Schacht, former Reichsbank president, engaged Albert Speer, Reichsminister for Production in lively banter, commenting: “I have read the indictment so many times myself that if they read it in court just once more, I’ll have it memorized.”

The Nazis talked animatedly with their lawyers just before court resumed.

Keitel and Col. Gen. Gustav Jodl, former chief of the general staff and Hitler’s military adviser, stood in neatly pressed uniforms. Dr. Franz Exner of Munich University, Jodl’s counsel, wore a purple robe.

Third count completed

Early in the afternoon session the French completed reading the third count of the indictment, recounting Nazi conscription of foreign labor, brutal Germanization of occupied territories, the killing of hostages and the plunder of public and private properties.

The deputy Soviet prosecutor then started reading the fourth count – “crimes against humanity.”

The Red Army colonel, in khaki tunic and blue trousers, spoke with a classroom singsong into the microphone.

Doenitz, his craggy face impassive, was the only Nazi who seemed to remain entirely oblivious to the Russian prosecutor. The charges in his case concern activities on the high seas against the Western Allies.

After the fourth count had been read, Mr. Alderman then read Appendix A, stipulating individual crimes charged to the defendants.

Goering shook his head negatively and smiled warmly when Mr. Alderman described him as an SS general. But he nodded at allegations: “He promoted the accession to power of the Nazi conspirators and the consolidation of their control over Germany.”

Hess, when named, sucked in his thin lips, turned to Ribbentrop and muttered. Afterward he seemed to be almost smiling. His deep-socketed eyes glittered under black shaggy brows.

Bormann’s misdeeds were read out, although he has been missing since the battle of Berlin.

The American prosecutor also read charges against Robert Ley, the Nazi labor chief, who hanged himself in the Palace of Justice jail after writing a treatise saying Germany had blundered by persecuting the Jews.

Despite the removal of Gustav Krupp from the indictment list last week, Mr. Alderman also read the allegations of his transgressions. The aged munitions and steel magnate was excused from trial because of senile softening of the brain.

Mr. Alderman finished Appendix A, and without pause read Appendix B, which in general terms sought to establish the criminality of the Nazi governmental, political, police and quasi-military organizations together with the German general staff.

The court session ended officially for the day at 5:05 p.m. (11:05 a.m. EST).

Schacht glares defiantly

Hitler’s henchmen had been brought into the small, oak-paneled courtroom about 20 minutes before the opening of the trial.

Guards formed a solid phalanx for nearly a quarter of a mile around the Palace of Justice in the bomb-battered city that once was the shrine of Hitlerism and now is the scene of the unprecedented trial to convict for all eternity the 12-year scourge of German aggression that sought to rule the world for a thousand years.

Before the proceedings opened, Justice Lawrence and his associate judges from the three other powers, first had to dispose of several preliminaries.

An inter-Allied psychiatric report, prepared at Soviet request, awaited the high tribunal’s acceptance. It found Streicher sane.

Recommendations on Hess

Independent reports by psychiatric commissions from each of the four powers were made before the tribunal, with recommendations concerning the ability of Hess to defend himself.

The American psychiatrists were reported to have found Hess incapable of defense and would so advise the tribunal. British alienists also were believed to have advised the tribunal that Hess’ purported amnesia rendered him incompetent at the present time. Soviet and French psychiatrists were said to have stressed that Hess’ loss of memory was a refuge sought in order to escape punishment.

Military authorities have taken every precaution to prevent any weapons or firearms from being smuggled into the courthouse.

Col. B. C. Andrus, commander of the security guard, told correspondents their typewriter cases would be subject to examination by American troops stationed inside and outside the court building. Women were told their handbags would be subject to scrutiny.

Soldiers are posted even on the roof of the court, and an American tank is stationed near the building.

High Nazis’ tension decreases on eve of beginning of trial

NUERNBERG (AP) – Relief was evident in the criminal wing at the Nuernberg jail last night as word reached the Nazi arch-criminals that the time had come for them to explain to humanity, if they could, how and why they acted that way.

Hermann Wilhelm Goering, No. 2 Nazi and former Luftwaffe chief, sat happily on the side of his bunk. He had just received word that his five-year-old daughter, Etta, had been reunited with his wife who has been under technical house arrest in Bavaria for the last seven weeks.

“That takes care of my last worry,” said the big Nazi. “I go into this trial as I always went into battle – eagerly.”

A few steps away Rudolf Hess, who has been an enigma since he flew to Scotland in a borrowed Messerschmitt four years ago, smiled wanly and commented, “I’m glad for the others. As for me, I’m different from most people in not taking life so seriously.”

Erich Raeder, grand admiral and former navy chief, who spent the first part of his captivity in Russian hands and reached Nuernberg singing the praises of his captors, turned at once to practical matters. "If my laundry doesn’t come, I’ll have to stand trial in my under wear.”

Conscience clear

A nervous Fritz Sauckel, “SS” and “SA” general, put it this way, “I didn’t kill anybody. My conscience is clear.”

Arthur Seyss-Inquart, former Nazi chancellor of Austria and later commissar for the Netherlands, sat hunched over his trial defense notes. He glances up with a wolfish grin.

“After the catastrophe and the defeat, we’ve been through I can’t think of a single thing that could possibly be less interesting or more unimportant than what happens to me,” he said.

Hans Frank, former Nazi governor of Polish territories, seemed clumsily grateful for the visit. He was very near hysteria, but held himself, “It’s all in God’s hands and I’m calmer than I’ve ever been.”

Hans Fritzsche, one-time Nazi editor and propagandist, said “after the last six months of uncertainty it’s a pleasure to get down to cases.”

Statement promised

Baldur von Schirach, who molded the Reich’s children into a sort of unholy crusade in the name οf the Fuehrer, promised a startling statement, “Their eyes will bulge.”

Then there was Julius Streicher, Nazi editor of the anti-Jewish paper Der Sturmer. He was already in bed. He climbed to his feet and bowed. “If everybody had a conscience as clear as mine, they’d sleep well, too.”

Franz von Papen, former Nazi diplomat and wartime ambassador to Turkey, tall and gaunt in his underwear, also said his conscience was clear.

Not so with Joachim von Ribbentrop, architect of Hitler’s foreign policy. “I’m unconcerned about tomorrow – but I ought to have more time to prepare my defense.”

Two who said they were relaxed and ready to face anything the prosecution might care to throw at them were Wilhelm Keitel, chief of the German high command who signed the unconditional surrender at Berlin, and Alfred Jodl, colonel-general and chief of staff of the German Army.

Rosenberg nervous

Alfred Rosenberg, director of the ideological training of the Nazi Party, justified the anxiety and strain that caused him to shift excitedly about his narrow cell saying, “It’s only human to be nervous.”

Karl Doenitz, grand admiral of the German Navy, accepted the situation complacently. He said, “I’m reconciled to the worst.”

Walther Funk, former Nazi press chief, who is ill, protested weakly against the scheduled lengthy two-and-a-half-hour morning and afternoon sessions.

Hjalmar Schacht, former Nazi economics minister, said, “I have always believed a man with a clear conscience had nothing to fear.”

The last was Constantin von Neurath, the man Ribbentrop replaced as foreign minister. “There are some hard words in the indictment. We’ll see.”

Countess sends love notes to Kaltenbrunner

NUERNBERG (AP) – An ardent love letter from a blond Prussian countess was in the hands of American authorities today for delivery to Ernst Kaltenbrunner, former Nazi chief of criminal police, who lies stricken with a brain hemorrhage.

Maj. Robert Matteson of St. Paul, Minnesota, American expert on Kaltenbrunner’s tangled marital affairs, described her as “24 years old, honey haired and with blue eyes.”

He said she was with Kaltenbrunner in a little Austrian love nest when he was arrested, and described herself as a “180 percent Nazi.”

Maj. Matteson said her love notes to Kaltenbrunner were forwarded with an appeal to Allied authorities for the right to testify in his defense.

Maj. Matteson described the young woman as being particularly scornful of Frau Kaltenbrunner, legal wife of the war crimes defendant.

The Pittsburgh Press (November 21, 1945)

Jap attempt to kill Stalin told at trial

Jackson says Nazis plotted war on U.S.

NUERNBERG (UP) – Robert H. Jackson charged before the Nazi war crimes court today that Germany and Japan plotted an attack upon the United States from both the Atlantic and the Pacific in 1940 or early 1941.

He said that in January 1939, Japan sent 10 assassins into Russia with orders to try to kill Joseph Stalin.

Mr. Jackson revealed the new charges as he delivered “the case for civilization” before the United Nations Tribunal, where 20 of Adolf Hitler’s cohorts were on trial for their lives.

The court summarily rejected a plea by the Nazis that the case be thrown out of court on grounds that there was no basis for it in international law.

Plead not guilty

The 20 Germans entered pleas of not guilty. Hermann Goering tried to make a speech. He sat down sulkily when Lord Chief Justice Sir Goeffrey Lawrence curtly told him he was out of order.

A 21st defendant, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, who was stricken with a cerebral hemorrhage, took a turn for the worse tonight. A physician said, “There is nothing that can possibly be done for him except wait and watch him die.”

Mr. Jackson gave a preview of the evidence which will be presented, declaring that the case would be proved from the lips and records of the Nazis themselves, noting that the Nazis had a “Teutonic passion for thoroughness in putting things on paper.”

He revealed for the first time that captured documents had disclosed that following the signature of the Axis pact in 1940, Germany actively planned with Japan for war against the United States from both the Atlantic and Pacific approaches.

As early as January 31, 1939, he disclosed, Tokyo reported to Berlin that they had sent 10 Russians, armed with bombs, into the Soviet Union with orders “to kill Stalin.” What happened to the would-be bomb-throwers was not disclosed.

Won’t escape justice

The defendants quailed as Mr. Jackson told them that even in the unlikely event that they should escape conviction at Nuernberg they will not be freed. Instead, he warned, they will be turned over to the individual United Nations where they are wanted for specific crimes.

At one point Mr. Jackson enlarged upon his prepared text to quote a letter by Alfred Rosenberg, Nazi ideological leader and specialist on Russian affairs, in which Rosenberg reported that only 600,000 of an estimated 3,600,000 Russian war prisoners were able to work. The remainder, he reported, had been exterminated or were too ill of wounds or disease to work.

Whispering barred

Defendants were not permitted to whisper among themselves while in the courtroom. At one point an American MP private tapped Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel on the head with a rolled-up newspaper when he persisted in talking.

Mr. Jackson told the four-power tribunal sitting in the Palace of Justice that the Nazi leaders were symbols of evil. They must be found guilty, he said, to show the world that international greed and cruelty cannot go unpunished.

As Mr. Jackson relentlessly drove home point after point in his 21,000-word denunciation, Goering frowned and slumped low in his seat. All the defendants except Rudolf Hess, Baldur von Schirach and Hjalmar Schacht wore earphones to hear the running German translation.

“These prisoners represent sinister influences that will lurk in the world long after their bodies have returned to dust,” Justice Jackson said.

Prosecutes first count

The defendants, he said, have so identified themselves with the philosophies they conceived and forces they directed that “any tenderness to them is a victory and an encouragement to all the evils which are attached to their names.”

Mr. Jackson was prosecuting the first count of the four-part indictment. This count, sponsored by the Americans, charges the defend-ants with conspiracy to wage aggressive war. He emphasized that the American case was aimed squarely at the Nazis and their organizations, not at the German nation.

“The German people should know by now that the people of the United States hold them in no fear, and in no hate,” he said.

Cites tortures

The accused Nazis “have subjected their European neighbors to every outrage and torture, every spoilation and deprivation that insolence, cruelty and greed could inflict,” Mr. Jackson said. “They have brought the German people to the lowest pitch of wretchedness, from which they can entertain no hope of early deliverance.”

Mr. Jackson said that the Kellogg-Briand Pact to outlaw war, which the defendants are accused of violating, was the first major step toward ending the menace of warfare in the modern world.

The United Nations Organization, he said, is another step, and the charter providing for the four-power war crimes trial and the trial itself “another step in the same direction – juridical action of a kind to ensure that those who start a war will pay for it personally.”

“The real complaining party at your bar is civilization,” he told the judges representing Britain, Russia, France and the United States.

“Civilization does not expect you to make war impossible. It does expect that your juridical action will put the forces of international law, its precepts, its prohibitions and most of all, its sanctions on the side of peace, so that men and women of good will in all countries may have ‘leave to live by no man’s leave, underneath the law.’”

Mr. Jackson’s address came in the second day of the trial. Prosecutors for Britain, Russia and France will present the cases on the counts of actual waging of aggressive war, and of committing war crimes against humanity.

Crimes of Nazis detailed in address by Jackson

NUERNBERG, Germany (UP) – The following are some sidelights of Justice Robert H. Jackson’s opening address before the War Crimes Tribunal:

Crimes against Jews: “What we charge against these defendants is not those arrogances and pretensions which frequently accompany the intermingling of difficult peoples… It is my purpose to show a plan and a design, to which all Nazis were fanatically committed, to annihilate all Jewish people.”

Gas wagons: “We of the Western world heard of gas wagons in which Jews and political opponents were asphyxiated. We could not believe it. But here we have the report of May 16, 1942, from the German SS officer, Becker, to his supervisor in Berlin which tells this story:

“‘Gas vans in C group can be driven to execution spot, which is generally stationed 10 to 15 kilometers from main road, only in dry weather. Since those to be executed become frantic if conducted to this place such vans become immobilized in wet weather.’”

Concentration camps: “Inmates were compelled to execute each other. In 1942 they were paid five reichsmarks per execution, but on June 27, 1942, SS Gen. Gluecks ordered commandants of all concentration camps to reduce this honorarium to three cigarettes…

“Under the Nazis, human life had been progressively devalued until it finally became worth less than a handful of tobacco – ersatz tobacco. There were, however, some traces of the milk of human kindness. On August 11, 1942, an order went from Himmler to the commanders of 14 concentration camps that ‘only German prisoners are allowed to beat other German prisoners.’”

Czechoslovakia: “Fears… were lulled by an assurance to the Czechoslovak government that there would be no attack on the country. We will show that the Nazi government already had detailed plans for the attack. They even gave consideration to assassinating their own ambassador at Prague in order to ¢reate a sufficiently dramatic incident.”

Poland: “Hitler told his staff on May 23, 1939, ‘we cannot expect a repetition of the Czech affair. There will be war.’ On August 22, when he told members of the High Command when military operations would begin, he said for propaganda purposes he would provocate a good reason. ‘It will make no difference,’ he announced, ‘whether this reason will sound convincing or not. After all the victor will not be asked whether he talked the truth or not. We have to proceed brutally. The stronger is always right.’”

The Evening Star (November 21, 1945)

Nuernberg court told of Jap plot to kill Stalin

Jackson bares Nazis’ plan to attack U.S.; 20 plead not guilty

By Wes Gallagher, Associated Press foreign correspondent

NUERNBERG (AP) – Justice Robert H. Jackson, chief American prosecutor opening America’s case against the 20 Nazi warlords facing the International War Crimes Tribunal, said today the Germans planned as far back as 1940 to attack the United States.

He said Nazi records also dis closed that the Japanese planned to assassinate Marshal Stalin in 1939 through the use of Russian traitors.

Heinrich Himmler, Nazi leader, left a written record of a conversation with Gen. Oshima, Japanese ambassador at Berlin, on January 31, 1939, Mr. Jackson said. In that record Himmler wrote: "He [Oshima] had succeeded up to now to send 10 Russians with bombs across the Caucasian frontier. These Russians had the mission to kill Stalin. A number of additional Russians, whom he also had sent across, had been shot at the frontier.”

Plead innocent to charges

In rapid-fire order the once-powerful Nazis pleaded Innocent to charges of engulfing the world in a bloodbath. In his opening 20,000-word statement to the court Justice Jackson promised that the defendants would be convicted by the Nazis’ own meticulously kept records.

Mr. Jackson talked all day, except for the brief pleadings at the start and during a futile maneuver of defense lawyers to have the whole trial quashed.

Reading from German records, he said German Gen. Falkenstein wrote on October 29, 1940, that “the Fuehrer is at present occupied with the question of occupation of Atlantic Islands with a view to prosecution of the war against America at a later date.”

In March 1941, Justice Jackson said, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, chief of the German high command, issued a secret directive that "the Fuehrer had ordered instigation of Japan’s active participation in the war.”

Hectic 10 minutes

The court knocked the main defense prop from under the Nazi chieftains when it abruptly denied their claims that they could not be tried for war guilt under existing international law.

The defense pleas were entered in a hectic 10 minutes, with responses varying from the dog-like bark of “no” from Rudolf Hess, Hitler’s one-time deputy, to a passionate reply of “not guilty in the eyes of God” from Baldur von Schirach, Hitler youth chief.

The dramatic high point of the morning session was reached when Lord Justice Geoffrey Lawrence, presiding, called the defendants forward one by one, warning them to plead merely innocent or guilty and to refrain from speeches which they would be permitted to make later.

Despite the warning, Hermann Goering lumbered to the microphone with a prepared speech in his hand, and attempted to read it.

Justice Lawrence halted him. Then, with an angry grimace, Goering intoned: “I declare myself in the sense of the indictment not guilty.”

He waddled back to his seat.

Ribbentrop still shaky

Hess’ barked “no” was officially recorded as “not guilty.” The court has not yet ruled on his sanity, but since he was permitted to plead it was assumed he would be tried with the rest.

The court called Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, still shaky from his near-collapse yesterday, when he was treated with sedatives.

“Not guilty,” he announced.

One by one the other Nazi leaders entered their pleas.

When the roll of the accused Nazi leaders had been called, Justice Lawrence ruled that Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Nazi security chief who was unable to appear because of a cranial hemorrhage, would be tried in absentia.

Justice Lawrence tightened the rules for trial procedure, when he ruled in answer to another protest that counsel cannot talk to defendants in court except by written note.

Listen closely to Jackson

When Justice Jackson, dressed in a black morning coat, stepped to the center of the courtroom and began reading his statement, the Nazi defendants leaned forward and listened closely, in marked contrast to their indifference to the proceedings yesterday.

When Justice Jackson solemnly stated that the Nazi leaders would be convicted by their own documents, Hans Frank, Hitler’s ruler over conquered Poland, laughed aloud. There were no smiles from the others, however.

When Justice Jackson charged that the burning of the Reichstag in 1933 was a Nazi plot to open the way for a drive against Communists, Goering heaved himself up like a wounded bull.

His fat face showed hard muscle lines shooting all the way back to his ears. He sat tense for a moment, then slowly relaxed.

Justice Jackson said the Nazi chieftains “have subjected their European neighbors to every outrage and torture, every spoliation and deprivation that insolence, cruelty and greed could inflict.

“They have brought the German people to the lowest pitch of wretchedness, from which they can I entertain no hope of early deliverance. They have incited domestic violence in every continent.”

Real complainant ‘civilisation’

He said the real complaining party in the trial was civilization, which “is still a struggling and imperfect thing.”

“It does not plead that the United States or any other country has been blameless of the conditions which made the German people easy victims of the blandishments and intimidations of the Nazi conspirators.

“But it points to the dreadful sequence of aggressions and crimes I have recited – it points to the weariness of the flesh, the exhaustion of resources and the destruction of all that was beautiful or useful in so much of the world, and to greater potentialities for destruction in the days to come.”

Among the nations the United States, having sustained the least injury, is perhaps in a position to be the most dispassionate, he said.

“But while the United States is not first in rancor, it is not second in determination that the forces of law and order be made equal to the task of dealing with such international lawlessness.”

Concedes lack of precedent

Justice Jackson conceded there is no judicial precedent for the charter under which the tribunal exists, but he said international law grows, like common law, through decisions reached from time to time “in adapting settled principles to new situations.”

Hence, he asserted, “I am not disturbed by the lack of judicial precedent for the inquiry we propose to conduct.”

In concluding his statement, Justice Jackson told the tribunal: “Civilization asks whether law is so laggard as to be utterly helpless to deal with crimes of this magnitude by criminals of this order of importance.

“It does not expect that you can make war impossible. It does expect that your juridical action will put the forces of international law, its precepts, its prohibitions and, most of all, its sanctions, on the side of peace, so that men and women of good will in all countries may have ‘leave to live by no man’s leave, underneath the law.’”

Engage in conversation

The prisoners exhibited increased friendliness among themselves and engaged in animated conversations before the trial reconvened for the afternoon session.

Only a third of Justice Jackson’s opening statement had been read at the morning session. As he continued, Hess alone among the defendants did not put on his earphones to hear the German translation.

The muscles in Julius Stretcher’s neck twitched and he stared at Justice Jackson as the prosecutor accused him of a part in the Nazi plan to exterminate the Jews of Europe. Frank scowled at Justice Jackson when he mentioned charges of his part in the anti-Semitic campaign.

Frank shook his head negatively when Justice Jackson spoke of executions in “gas wagons.” Then the prosecutor held before the court an opened book containing an SS general’s report on the destruction of the Warsaw ghetto.

Desires visit to Dachau

Grand Adm. Erich Raeder, Goering and Hjalmar Schacht, former Reichsbank president, all made notations when Justice Jackson declared he found no instance in which any defendant opposed the policy of destroying the Jews.

Justice Jackson, his voice alternately sarcastic and scornful, expressed the hope that the tribunal would visit the nearby Dachau concentration camp, where 40 other Nazis presently are on trial before a U.S. military court for war crimes.

He read an order to the German armed forces from Hitler telling the army to have suspects in occupied countries “disappear without a trace” as a punitive measure against unfriendly acts.

When he accused Arthur Seyss-Inquart of complicity in the betrayal of Austria, Justice Jackson turned his gaze on the defendant. Seyss-Inquart, chin on hand, listened intently.

Justice Jackson read a Hitlerian order that American and British fliers parachuting into Nazi territory were to be treated as criminals instead of prisoners of war. Goering and Keitel scribbled busily.

The American prosecutor read a Nazi order for putting prisoners to work on war jobs and declared: “No more flagrant violation of the rules of war can be imagined.”

Challenge to validity

The defense motion challenging the validity of the proceedings asked that the tribunal “secure from internationally recognized experts on international law an opinion about the legal basis for this trial.”

The motion had been filed by German counsel representing all the accused Nazis except Hjalmar Schacht, former Reichsbank president.

The attorneys contended that the trial violated the “generally recognized principle of modern criminal procedure,” because the Allied powers have made themselves "everything in one: Creator of the Charter of the penal law, prosecutor and judge.”

Day 3

-

Prosecution trial brief A – Common objectives, methods and doctrines of the conspiracy

-

Prosecution trial brief B – The acquiring of totalitarian control over Germany

-

Prosecution trial brief C – Consolidation of control; utilization and molding of political machinery

-

Prosecution trial brief F – Purge of political opponents; terrorization

-

Prosecution trial brief H – Suppression of Christian churches in Germany

-

Prosecution trial brief I – Adoption and publication of the program for persecution of the Jews

-

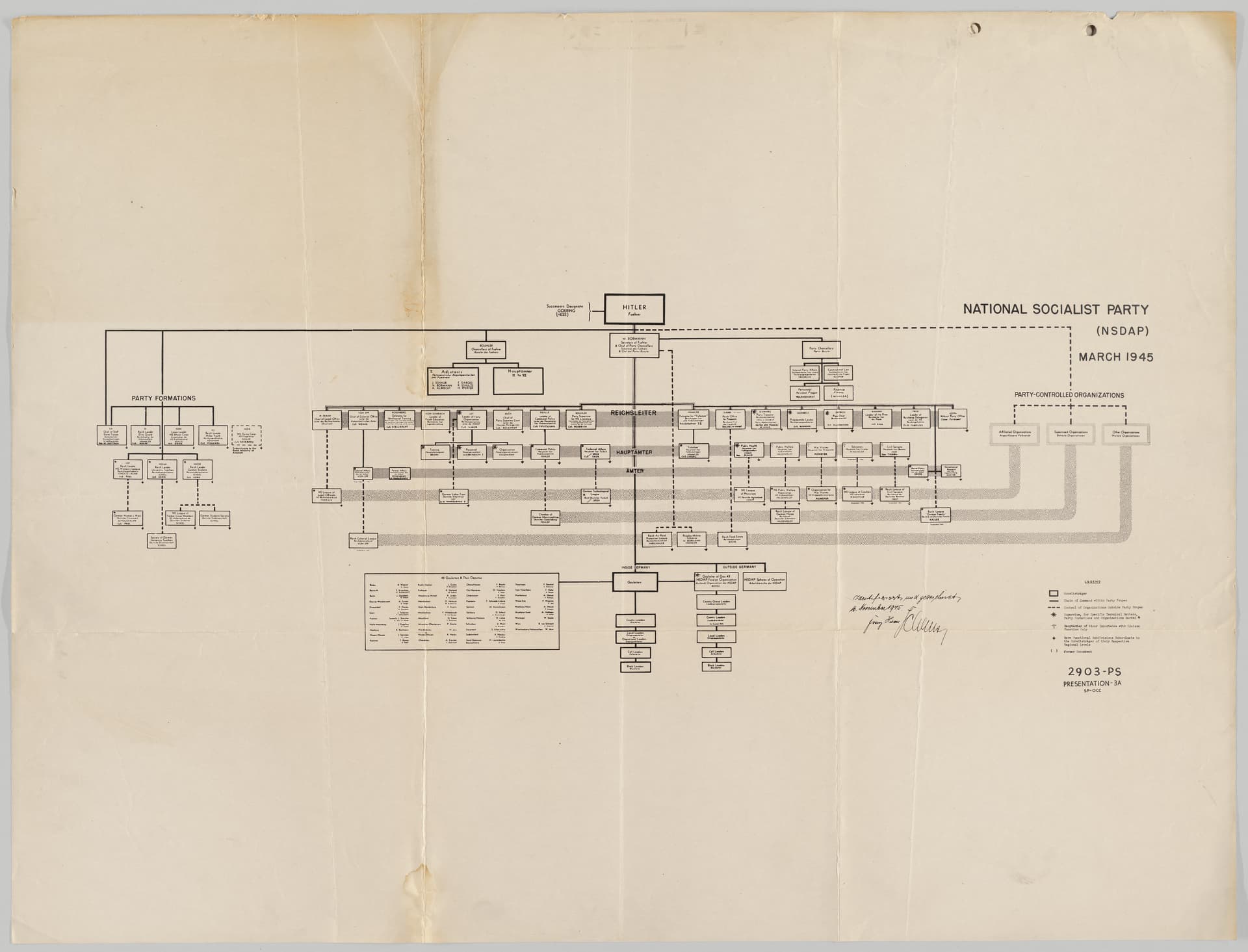

Chart of NSDAP, March 19, 1945, with affidavit of Franz Xaver Schwarz attached

The Evening Star (November 22, 1945)

Nazis’ 1933 plot to seize power traced at trial

American prosecutor shows party’s rise back to 1919

NUERNBERG (AP) – American prosecutors, plunging directly into the first count of the indictment against 22 Nazi leaders on war crimes charges, showed today, from the minutes of the meetings of Adolf Hitler’s first cabinet in 1933, how the Nazi Party conspired to take over the German government by illegal means in the Reichstag.

Tracing the rise of the party back as far as 1919, Maj. Frank Wallis, assistant American prosecutor, produced the records of meeting after meeting of Hitler’s initial cabinet, surprising the defendants themselves.

Maj. Wallis showed how the young Nazi government abolished personal liberties in Germany after the Reichstag fire and disclosed how the noisy demonstrations in the Reichstag after 1930 made orderly parliamentary progress impossible.

An affidavit signed by Wilhelm Frick, once “protector” of Bohemia and Moravia, the day before the trial opened told how Hermann Goering carried out the 1934 blood purge in Northern Germany on Hitler’s orders, after Heinrich Himmler convinced the Fuehrer of a plot.

“Many people were arrested,” the Frick affidavit said. “Something like a hundred, or even more, were killed. All this was done without resort to legal proceedings. They were just killed on the spot. Many people were killed – I don’t know how many, who actually did not have anything to do with the putsch.”

Mass of documents offered

The third day of the trial brought introduction of a mounting pile of documents, ranging from intimate diaries of leading Nazis to carefully worded secret plans of the German high command, before the International Military Tribunal.

As today’s session opened, the four-power court ruled that Jew-baiter Julius Streicher was sane and must stand trial, and denied a defense motion which asked postponement of the trial of Martin Bormann, Hitler’s missing deputy, who is being tried in absentia.

The tribunal accepted a medical board report finding Streicher sane and Lord Justice Geoffrey Lawrence, presiding, ruled that his trial will proceed.

Ernst Kaltenbrunner, former chief of the Nazi security police who is unable to appear in the war guilt trial because of a cranial hemorrhage, was slightly improved today after the administration of penicillin. He was reported in a serious condition yesterday.

Nails in high spirits

For the first time since the trial opened two days ago, the accused German leaders appeared in high spirits. Smiling all the time, Goering chatted animatedly with defense counsel. Rudolf Hess, who has had only a vacant stare for most of the court proceedings, laughed for the first time as he talked with former Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop. Even the stem high command generals, Wilhelm Keitel and Alfred Jodl, were smiling.

Several hundred Reich documents selected from the file of more than 2,500 amassed by American investigators will outline in the Germans’ own words the scheming and aggression by which Hitler and his henchmen led the world into World War II, declared Col. Robert Storey of Dallas, Texas, an assistant American prosecutor.

The vital documents, many of them seized by special Army intelligence teams, range from Alfred Rosenberg’s diary and letters discovered behind the false wall in an Eastern Bavarian castle to top-secret Luftwaffe records secreted in Hitler’s proposed Alpine redoubt.

Others came from salt mines and buried caches, Col. Storey told the court. He credited Maj. William S. Coogan with most of the responsibility for screening and analyzing the tons of such material which were sifted for evidence against the Germans on trial.

Movies to show Nazi heyday

The prisoners were in the box well before court convened promptly at 10 a.m., and they gazed with interest at the large white screen at the end of the courtroom, on which the prosecution intended to project motion pictures of Nazidom in its heyday – more evidence against the German leaders. The films will be familiar to the Germans. They are a Nazi product.

As Col. Storey finished his presentation, Justice Lawrence conferred with his colleagues on the bench, and announced that the tribunal accepted the United States method of presenting evidence.

Assistant Prosecutor Ralph C. Albrecht of New York offered a chart of the construction of the Nazi Party, and the defendants with the exception of Goering, leaned forward and watched the blackboard with great interest.

Mr. Albrecht was attempting to establish the chain of the Nazi Party command and prove the leaders could be only National Socialists. The chart showed how each defendant fitted into the system and the part he played. He noted that Goering and Hess were Hitler’s chosen successors – and Hess leaned forward and looked inquiringly at Goering, seated beside him.

Admits moral gilt

There was some indication that Hitler’s henchmen themselves were beginning to understand the true significance of the world’s abhorrence of Naziism and its works. This appeared evident in the declaration of the attorney for Hans Fritzsche that the one-time deputy to Propaganda Minister Paul Joseph Goebbels was “ready to acknowledge moral guilt for having placed his energies at the disposal of the Nazi regime.”

His counsel said Fritzsche reached this conclusion after learning “all about the concentration camps and the other evidence produced.” But Fritzsche did not consider himself criminally guilty because he was “carrying out orders,” his counsel said.

Whether any of the other defendants felt the same way was not known, but it was noted that a number of them replied “not guilty in the sense of the indictment” when they made their pleas. Fritzsche was one of those who used those words.

Defense motion still open

The way still was open, apparently, for hearing on the German attorney’s motion that the court was not authorized to try the defendants – possibly after completion of the prosecution’s case. The court told the defense that remaining arguments for the motion might be heard at a later date. The motion was denied by the court as the second day’s proceedings opened yesterday.

Before the morning session was adjourned at 12:27 p.m., the rise to power of the Nazi Party in the early 1930s was traced by a chart which Mr. Albrecht said “has been certified as to accuracy in an affidavit by the defendant, Frick.” The rest of the defendants gazed without love at the uncomfortable Frick.

Goering, with lips pursed tightly, furiously scribbled notes as he held with one hand his earphones relaying the translation of the prosecutor’s statement.

Pointing out how the Nazis took over all power although not representing all the people, Mr. Albrecht declared that “only one cabinet member had the strength of character to remain out of the Nazi Party.”

This was a reference to Hjalmar Schacht, former Reichsbank president.

“We are moving in a somewhat shadowy laid,” Mr. Albrecht said in tracing the usurpation of legislative powers by the Nazis, “because many of these acts were by decrees that were secret. Many were never published and were kept from the German people.”

After the noon recess, Maj. Wallis went back to 1919 tracing the rise of the Nazi Party.

He asked the court to take judicial note of the aims of the party, which were the overthrow of the Versailles treaty, the acquisition of territory lost by Germany, the acquisition of areas inhabited by “racial Germans” and the acquisition of other territory or “living space.”

He declared the Nazis announced again and again they would achieve these objectives by any means whatsoever, legal or illegal or by war.

He quoted Hitler as saying he was ready “to tear any one to pieces” who dared interfere with the Nazi aims. Maj. Wallis charged that the abortive beer cellar putsch of 1923 in Munich was an indication that the Nazis intended to proceed illegally.

Maj. Wallis produced the original minutes of the first Hitler cabinet meeting and quoted Hitler as saying he could suppress the Communist Party but he feared a strike would result.

Liberties abolished

Under the impact of disturbances caused after the Reichstag fire, Maj. Wallis charged, personal liberties were abolished by decree. He said at the succeeding cabinet meeting Frick and others urged passage of an enabling act, so worded that the constitution could be broken.

The defendants were visibly moved when the prosecutor produced minutes of the meetings of Hitler’s first cabinet, which included von Papen, Frick, Walther Funk and Goering – all on trial. The minutes told in themselves how the Nazis plotted to take over the government by illegal means in the Reichstag.

Maj. Wallis said that shortly before the elections of March 31, 1933, Frick announced in the cabinet that concentration camps would be established. By March 24, when the Reichstag convened after the election, an enabling act was passed while many members were absent because they had been detained illegally.

The act virtually set aside the constitution and gave the Nazis unlimited power.

Defense attorneys at Nuernberg praise Jackson statement

NUERNBERG. Germany (AP) – German defense attorneys yesterday praised Justice Robert H. Jackson’s formal indictment of their Nazi clients as “lofty, noble, well reasoned.”

Franz Exner, Munich defense counsel for Col. Gen. Alfred Jodl, said Justice Jackson had “formulated the international law of the future,” and said he hoped principles stated in the indictment would become part of accepted international law.

Editorial: For history to unravel

In his masterly opening statement to the international tribunal at Nuernberg yesterday, Mr. Justice Robert H. Jackson, chief United States prosecutor of accused Nazi war criminals, explained that “We are not inquiring into the conditions which contributed to starting this war. They are for history to unravel.”

We must also leave for history to unravel some of the complexities presented by this proceeding. They do not lie so much in the legalities of the undertaking as in the possible fruits of that bold concept which Justice Jackson has endeavored to plant – that individuals, under international law, are from this time on liable to punishment, as common criminals, for the parts they play in perpetration of newly defined “crimes against the peace” and “crimes against humanity.”

It may be that in times to come a grateful world will look back on this symbolic proceeding at Nuernberg in much the same light that we now regard the precedents written at Runnymede and at Philadelphia. But for the present we must keep before us the danger which Mr. Jackson has himself recognized and anticipated – the danger that instead of establishing a new concept of international law, the judgment of the world will be that the only lesson taught at Nuernberg was the old lesson that the victors always have and always will be the judges of the vanquished.

Mr. Jackson referred to that danger after the four powers had agreed, in London last August, to the Charter under which the trials are now being held. He referred to it again yesterday, when he said that personal punishment, to be suffered in the event a war is lost, will not be enough of a deterrent to stop those from engaging in aggressive war who believe they can win. If they are to live, the new chapters of international law written at Nuernberg must be accepted by the peoples of the world. “While this law is first applied against German aggressors,” Mr. Jackson said, “the law includes, and if it must serve a useful purpose it must condemn, aggression by any other nation, including those which now sit here in judgment.”

Are we prepared now to condemn a fellow-judge nation which later may be found guilty, in the eyes of the world, of “crimes against humanity” or “crimes against the peace”? Are we willing to enforce such judgment by going to war if necessary? Are we willing to accept the judgment of others as to the rectitude of our own future conduct? Forgetting the miserable human relics who await judgment at Nuernberg, and remembering only the principle invoked to try them, it is not difficult to understand how many things we are leaving for history to unravel.

Day 4

-

Prosecution trial brief D – Reshaping of education; training of youth

-

Prosecution trial brief E – Propaganda, censorship and supervision of cultural activities

-

Prosecution trial brief J – Militarization of Nazi-dominated organizations

-

Prosecution trial brief K – Economic aspects of the conspiracy

-

Prosecution trial brief L – In re: Aggressive War: Opening statement

The Pittsburgh Press (November 23, 1945)

Hitler-Jap plot against U.S. revealed

Discussed war long before December 7

NUERNBERG (UP) – Adolf Hitler and Jap Foreign Minister Yosuke Matsuoka discussed German-Jap cooperation in a war against the United States eight months before Pearl Harbor, evidence at the war crimes trial revealed today.

A transcript of notes taken at the Hitler-Matsuoka meeting was presented at the war crimes trial. It revealed that Japan and Germany both had laid down long-range plans for war with the United States.

The war crimes court also learned that Hitler had ordered shipments of armaments to Russia under the Russo-German economics pact giving top priority in the spring of 1940 because of the prompt Soviet deliveries of raw materials much needed by the German Army.

To accuse Krupp

Evidence disclosed that the Russians made deliveries of huge quantities of raw materials right up to the time of the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, and even rushed in rubber shipments by express train.

Francois de Menthon, chief French prosecutor, announced that a second war crimes indictment is being drawn up, naming prominent German industrialists, including Alfried Krupp, and that their trial would probably follow the present case.

While making their plans, both Hitler and Matsuoka expressed “hopes” that the war would not come.

Matsuoka asked Hitler for assistance in equipping Jap submarines.

Promised aid

Hitler, the notes revealed, promised that Germany would help Japan by whatever means possible and added that while Germany considered war with the United States “undesirable,” he already had made allowances for this contingency.

“Germany has made preparations so that no American could land in Europe,” he assured the Japs.

The notes said that Hitler told Matsuoka that Germany “would conduct a most energetic fight against America with her U-boats and Luftwaffe and due to superior experience, she would be vastly superior.”

“That’s quite aside from the fact that German soldiers naturally rank high above the American,” Hitler said.

Said he would fight

If Japan went to war with the United States, Hitler said, Germany would “immediately take the consequences” – apparently the Fuehrer’s way of saying Germany would join the war.

Matsuoka said that it was his personal conviction that a war between Japan and the United States could not be avoided.

The notes on the Hitler-Matsuoka conference were presented as the court received detailed information on deliveries under the Russo-German economic pact.

The evidence revealed that while Hitler ordered deliveries of arms and munitions speeded up to Russia, he already had his attack on Russia in mind.

After presentation in detail of the economic background of the Nazi operations, Prosecutor Sidney J. Alderman launched into the individual responsibility of the Nazi lenders for the crime of war.

The economic evidence disclosed that Dr. Hjalmar Schacht, the Nazi financial wizard; the Krupp interests and other German industrialists raised a three-million-mark slush fund to help Hitler’s rise to power.

Schacht, the evidence disclosed, was ringleader in the fundraising campaign and acted as host to an assembly of Ruhr industrialists who were called together at Hitler’s behest.

Agreed to raise fund

The industrialists, the evidence disclosed, agreed to raise the fund. The share of the great I.G. Farbenindustrie chemical combine in the fund was to be 10 percent.

It was announced that Russia is sending Foreign Affairs Vice-Commissar A. Y. Vishinsky, famous prosecutor of the Moscow purge trials, to Nuernberg.

It was believed Vishinsky might take over the Soviet prosecution of the case. He is accompanied by Soviet Judge Advocate Gorshenin.

Krupp letter offered

Among evidence placed before the court was a letter to Hitler from Gustav Krupp, head of the great Krupp arms firm who originally was named in the war crimes indictment but too ill to be brought to trial. Krupp wrote Hitler that the Nazi victory was in line with the hopes which he and his directors long had cherished.

In another letter to Hitler, Krupp, speaking as chairman of the German Association of Industry, submitted a plan which Hitler accepted for making the association an instrument of Nazi industrial policy.

Schacht quoted

Evidence concerning Schacht included a personal letter from him to Hitler, written in 1937, in which he said, “I have always considered the rearmament of the German people as a condition sine qua non for the establishment of the new German state.”

Asks to call Britons

The evidence was presented after Nazi Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop asked permission through his counsel to call six prominent British figures and “Gen. Wood of the U.S. Army” as witnesses.

Fritz Sauter, the former German foreign minister’s attorney, announced that he has filed an application to subpoena the prominent men. He did not identify what Gen. Wood he meant (There are several generals by that name in the American Army Register).

Von Ribbentrop’s list included Lord Beaverbrook, publisher of the powerful London Daily Express and close adviser of Winston Churchill.

Sauter identified Wood as an American general who had made a report before Congress quoting a statement by Mr. Churchill in 1936 that Germany should be destroyed. The attorney said he did not know Wood’s first name.

May call Molotov

He said he also was considering a request to call Soviet Foreign Commissar V. M. Molotov as a defense witness but had not decided whether to make the motion.

The court informed Sauter that it would be at least three weeks before it acts on the motion.

The other men on von Ribbentrop’s list are Lord Vansittart, formerly permanent undersecretary of the British Foreign Office; Lord Londonderry, secretary of state for air from 1931 to 1935; Lord Kemsley, one of Britain’s “press lords” and publisher of The Daily Sketch; Lord Derby, war minister during World War I and later ambassador to France, and Geoffrey Dawson, editor of The London Times during the Munich era. Mr. Dawson is dead.

The Evening Star (November 23, 1945)

Nazis fail to prevent admission of 10 surprise papers in trial

Prosecution says case on conspiracy for total war rests on documents

By Daniel De Luce, Associated Press foreign correspondent

BULLETIN

NUERNBERG (AP) – Ten days before the Germans attacked Poland in 1939 Hitler told his generals he had given orders “to kill without mercy all men, women and children of the Polish race or language” and that German troops wearing Polish uniforms would be used in an attempt to conceal the Nazi aggression, the American prosecution charged at the war crimes trial today.

NUERNBERG (AP) – Punishment of 20 of Hitler’s top aides was demanded today by the United States on charges of spreading the “atrocious doctrine” of aggressive warfare in a plot to murder millions throughout the world.

American prosecutors told the International War Crimes Tribunal that the main case against the Nazi leaders would rest on “10 documents never before revealed.”

Attempts to introduce the surprise documents brought a storm of futile protest, however, from German defense counsel. The session was adjourned for the day to permit study by lawyers for the accused Nazis.

Emphasizing the hopes of Allied nations that the charter of the International Military Tribunal outlawing aggressive war would open a new era of peace. Assistant American Prosecutor Sidney S. Alderman said punishment of the Nazis for planning world conflict was “the heart of the case.”

Heads of the vast Krupp steel empire and the I.G. Farben chemical trust, Thomas Dodd, another American prosecutor, charged, agreed to finance the Nazi Party as an antidote to Communism and later cooperated in a secret rearmament program.

Hjalmar Schacht was red-faced as he heard himself described from German documents as the financial wizard who was secretly appointed as “plenipotentiary for war economy” in 1935 and won the praise of a Reich general as “the man who made reconstruction of the German Army economically possible.”

The head of the great Krupp works, Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach – who was indicted but thus far has escaped trial because of illness – was shown by German records, Mr. Dodd asserted, to have aided in raising campaign funds for Hitler in 1933 and to have declared after Hitler’s rise to power that German industry “puts itself at your disposal.”

Dr. Rudolf Dix, Schacht’s counsel, declared at a recess that he was considering summoning American businessmen as witnesses for the defense.

Dr. Fritz Sauter, defense counsel for Joachim von Ribbentrop, already has formally requested the tribunal to subpoena five members of Britain’s House of Lords as witnesses in his trial.

Mr. Dodd linked German industrial interests and Schacht, former Reichsbank president, directly to the Nazi party even before the election which resulted in Hitler becoming Reichschancellor in 1933 with an affidavit from Georg von Schnitzler of the I.G. Farben firm.

Schnitzler said Schacht “acted as kind of a host” at a meeting in February 1933 of Hitler, Krupp, Albert Vogler, chief of the steel combine, and other industrialists.

Hitler warned the industrialists of the dangers of Communism, Schnitzler’s affidavit declared, and after the Nazi leader left the room “Schacht proposed to the meeting the raising of an election fund, as far as I remember, of 3,000,000 Reichsmarks.”

Schacht listens earnestly

Schacht, who protested in a recent interview that he had little to do with German rearmament, listened earnestly and jotted down notes as the affidavit and other documents were introduced.

One letter signed by the Reichsbank president and sent to Hitler January 7, 1939, said: “From the beginning the Reichsbank has been aware of the fact that successful foreign policy can be attained only by the reconstruction of the German armed forces. The Reichsbank therefore assumed to a very great extent the responsibility to finance rearmament in spite of the inherent dangers to the currency.”

Another of Schacht’s letters told of risking inflation in order to give the army all the funds it needed to assure “a successful foreign policy.”

The prosecutor read from the diary of former Ambassador William E. Dodd the statement that Schacht admitted to the American envoy in September 1934 that the Hitler party was absolutely committed to war and that the people were willing.

War preparations in 1934

A basic directive of the Reich Economic Ministry issued September 30, 1934, was introduced by the prosecution to show Hitler started preparing for war.

Lord Justice Geoffrey Lawrence, presiding, cut short the reading of the I.G. Farben Co. officials’ affidavit describing the 1933 meeting in which Schacht proposed raising campaign funds for Hitler, remarking that it seemed to prove merely that a meeting had been held.

At one time during the presentation of documents, Alfred Seidl, counsel for defendant Hans Frank, jumped to his feet to complain that some of the evidence had not previously been listed with defense counsel. He asked for a delay in the trial, but proceedings were resumed when Col. Robert G. Storey, an assistant American prosecutor, promised a better distribution system would be worked out.

The prosecution said secret German plans for war as early as February 22, 1933, were contained in the minutes of a working committee of “delegates for Reich defense” in which Field Marshal Keitel was quoted as saying:

“Secrecy of all Reich defense work has to be maintained very carefully. No document must be lost, since otherwise enemy propaganda would make use of it. Matters communicated orally cannot be proved, they can be denied by us in Geneva (League of Nations).

Deny Keitel in cabinet

As the fourth day of the historic trial opened, counsel for Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel declared that prosecution charts naming Keitel as a cabinet minister without portfolio were false and asserted that the general never participated in Hitler’s cabinet meetings.

Dr. Otto Nelte, Keitel’s attorney, said that although a secret cabinet council with which the high command chief was linked had been created by law February 4, 1938, the council never was appointed and held no session.

Justice Lawrence ruled that the prosecution documents were admissible and that the defense could later challenge material in them. Justice Lawrence announced that there would be no session tomorrow in order to allow defense counsel more time for consideration of documents.

Political phase completed

American prosecutors earlier wound up their evidence dealing with the political phases of Hitler’s bold grab for authority.

Zealous Nazi secret police as early as 1934 described Catholic Church opposition to their new regime as “unspeakable behavior,” and by 1942 Himmler ordered concentration camps to put priests of some nationalities at any kind of work.

This was disclosed yesterday by secret police files submitted in evidence before the tribunal. The documents showed a growing Nazi fury in the face of the passive non-cooperation on the part of the clergy.

Nazi defense lawyers offer autobiographies

NUERNBERG (AP) – Seventeen solemn defense attorneys participating in the war crimes trials submitted brief autobiographies to the Allied press today, showing that 13 never had joined the Nazi Party, two had been expelled, one never had his application accepted and one had been a Nazi since 1938.

The lone attorney who admitted being a party member of unquestioned standing was Dr. Alfred Seidl, who represents Hans Frank, the former governor general of Poland.

Dr. Fritz Sauter, counsel for Joachim von Ribbentrop, Hitler’s foreign minister, noted on his biographical sketch that he had been dropped from the Nazi Party in 1940 after five years’ membership, because he had defended Jews and Communists.

Julius Streicher’s counsel, Dr. Hans Marx, said he joined the Nazi Party in 1933 and was dismissed in 1935 but did not give the reason for his dismissal.

Of the entire group of attorneys, Prof. Herbert Kraus, co-counselor for former Reichsbank President Hjalmar Schacht, is the best known internationally. Kraus formerly taught at Princeton University and the University of Chicago and has written seven authoritative books on topics ranging from the Monroe Doctrine to the 1932 crisis in German democracy. The Nazis dismissed him from the Goettingen University faculty in 1937, but the British restored his professorship there last September.

Goering, with near-genius IQ, is natural leader, expert finds

NUERNBERG (AP) – Hermann Goering, with an IQ bordering on the genius rating, is the “natural born leader” of the 20 high Nazis being tried by the International War Crimes Tribunal, an American Army officer said today.

Maj. Douglas Kelley, former University of California psychiatrist, found the fat ex-Reichsmarshal had an intelligence quotient of 138 and that he still exerted a dominating influence over nearly all of the Hitler aides on trial.

“Goering is a natural born leader,” Maj. Kelley reported. “He and Doenitz and Schacht are the brainiest of the lot.

“Goering is the most aggressive and energetic. He keeps after the others to ‘maintain German dignity!’ If he has a phobia, it’s of being made to appear ridiculous. He asserts he is not afraid of any verdict. He says the Luftwaffe commander who asked so many of his best fliers to go to their deaths shouldn’t flinch at losing his own life.”

Maj. Kelley, who continually checks on the mental condition of all defendants, described former Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop as “wishy-washy”; Hans Frank, who got the title of “Butcher of Warsaw” while ruling Poland, and Arthur Seyss-Inquart, Hitler’s governor of Austria and later of the Netherlands, as the “most cold-blooded.”

The two admirals, Doenitz and Erich Raeder, and Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel and Col. Gen. Gustav Jodl are the "most philosophically composed,” Maj. Kelley said.

The Pittsburgh Press (November 24, 1945)

Ribbentrop may call Lady Astor to aid war crime defense

Other lading Britons on witness list

NUERNBERG (UP) – Lady Astor and other members of the so-called British Cliveden Set may be called as witnesses to defend Joachim von Ribbentrop in the war crimes trial, the former German foreign minister’s attorney said today.

Dr. Fritz Sauter, von Ribbentrop’s attorney, said, “Yes, probably” when asked if he intended to request the American-born noblewoman’s appearance. Yesterday Sauter said he wanted to call Lord Beaverbrook, Lord Kemsley and four other British leaders to help prove that Britain intended to attack Germany.

Met at country home

The Cliveden Set, about which Sauter was asked, was a group of prominent British men and women who met at Lady Astor’s country home, Cliveden, before the war seeking to promote better understanding with Germany.

The trial of the 20 Nazi leaders was in recess until Monday. Defense attorneys held a press conference in which they outlined their hopes to call a large number of prominent personages.

Lady Astor, most important figure mentioned, was the first woman member of the House of Commons, from which she retired this year after 25 years’ service. She was born Nancy Langhorne of Virginia.

Jewish banker sought

Hjalmar Schacht’s attorney said he wanted to subpoena the former director of the Bank Berliner Handelsgesellschaft, a Jew named Jeidels, to testify that Schacht helped him to emigrate to the United States.

The attorney for Rudolf Hess, Dr. Guenther von Rohrscheidt, said he was trying to call the Duke of Hamilton and the British physician who examined Hess when he parachuted onto the Duke’s Scottish estate in 1941. He said he was doing so without Hess’ knowledge because Hess “is unable to remember anything.”

Other desired witnesses are Winston Churchill’s nephew, Guiles Romilly, who was captured at Narvik, and Field Marshal Alexander’s son, who also was a German prisoner.

Frank fond of Poles

Hans Frank, charged with atrocities in Poland, wants to call two Poles to prove that he was personally “very much interested in the welfare of the Polish people” and that the atrocities were committed by the SS.

Evidence submitted by American prosecutors Jate yesterday included minutes of the meeting of the German High Command at Obersalzberg on August 22, 1939, when Hitler announced plans to attack Poland.

In a ranting oration he threatened to Fick Neville Chamberlain, then British Prime Minister, “in the belly before the eyes of all the photographers” if he tried to interfere.

Goering on table

The document said that Goering greeted the announcement by jumping on the table and shouting bloodthirsty thanks and bloody promises.

Hitler told the High Command that he would shake hands with Generalissimo Stalin within a few weeks on the common German-Russian border. He said he was sending elite units into Poland to kill without mercy all men, women and children of Polish race or language.