I was not looking forward to this sad day. Thank you Ernie for your insightful observations on our common human condition during the war. You will be missed as a friend to all, particularly, the infantryman.

The Pittsburgh Press (April 18, 1945)

Ernie Pyle dies in action

Famed war reporter killed by Jap bullet on Ie, off Okinawa

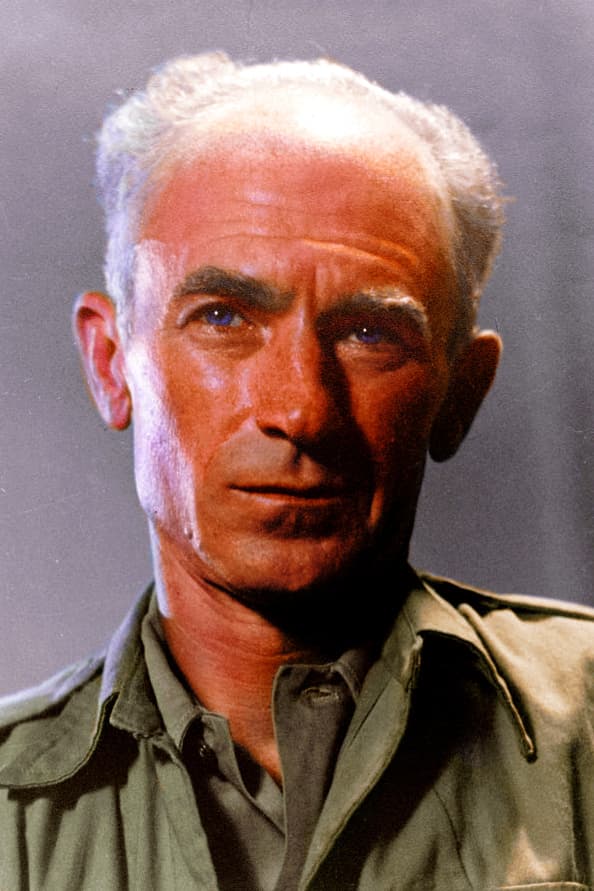

Ernie Pyle – He joins thousands of his beloved G.I. Joes.

WASHINGTON (UP) – Ernie Pyle, the greatest frontline reporter of this war, was killed in action this morning.

The skinny little Scripps-Howard and Pittsburgh Press war reporter – beloved of U.S. fighting men the world over – was killed by a Japanese machine gun bullet on the little island of Ie, off Okinawa.

He was killed, Secretary of the Navy Forrestal said, in the company of “the foot soldiers, the men for whom he had the greatest admiration.”

Vice Adm. Richmond Kelly Turner, commander of amphibious forces in the Pacific, reported from Guam that Mr. Pyle was killed outright about 10:15 a.m. Guam Time (Tuesday night ET) under Japanese machine gun fire on the outskirts of the town of Ie, on the island of Ie, four miles west of Okinawa.

Often close to death

He had come close to death countless times before – in North Africa, Sicily, Italy and France.

Mr. Pyle started covering the war in England and North Africa. He stayed with it, except for a brief furlough home, until the Americans were sweeping the Germans out of France.

Then he came home again, leaving the front, he explained, simply because he couldn’t stand the sight and smell of death any longer.

He didn’t want to go to war again, but he felt he owed it to America’s soldiers and sailors and Marines to report what they were doing in the Pacific.

He landed on Okinawa on what they called “Love Day” – the day of the first assault.

Truman expresses grief

The news of Mr. Pyle’s death saddened an already bereaved White House. A few moments after the report got out, President Truman said:

The nation is quickly saddened again by the death of Ernie Pyle. No man in this war has so well told the story of the American fighting man as American fighting men wanted it told. More than any other man he became the spokesman of the ordinary American in arms doing so many extraordinary things. It was his genius that the mass and power of our military and naval forces never obscured the men who made them.

He wrote about a people in arms as people still, but a people moving in a determination which did not need pretensions as a part of power.

Nobody knows how many individuals in our forces and at home he helped with his writings. But all Americans understand now how wisely, how warmheartedly, how honestly he served his country and his profession. He deserves the gratitude of all his countrymen.

Mr. Pyle was a foxhole reporter. He said he knew nothing about strategy or tactics. What interested him was the G.I. in the dust and the muck. So that is what he wrote about.

He had spent the years before the war writing a rambling column about places he had seen and people he had met.

He lacked the physique for war. He was slight, weatherbeaten, gray-haired, and balding. He was ill much of the time. He was no longer young – he would have been 45 on August 3.

But he liked people. When he went to war, he kept on writing about people. The people he wrote about were in fox-holes, so Emie spent a lot of time in foxholes.

Secretary Forrestal said in a statement that Mr. Pyle “was killed instantly by Japanese machine gun fire while standing beside the regimental commanding office of Headquarters Troops, 77th Division, U.S. Army.”

Mr. Forrestal added:

Mr. Pyle will live in the hearts of all servicemen who revered him as a comrade and spokesman. More than anyone else, he helped America to understand the heroism and sacrifices of her fighting men. For that achievement, the nation owes him its unending gratitude.

Secretary of War Stimson was shocked into momentary silence by the news. Then he said:

I feel great distress. He has been one of our outstanding correspondents. This is the first I have heard of his death. I’m so sorry.

Speaker Sam Rayburn voiced the sentiment of his congressional colleagues: “I think he was one of the great correspondents of all time.”

Once in North Africa, some German Stukas began dive-bombing and strafing the place where Ernie was. He dived into a ditch behind a soldier.

When the raid was over, he nudged the soldier and said, “Whew, that was close, eh?” The soldier didn’t answer. He was dead.

Mr. Pyle, saying over and over again that he was constantly afraid, went from near-miss to near-miss, from North Africa to Ie.

Once at Anzio a bomb knocked him out of his bunk. He reported it, but most of the column for that day was about the others who were in the hut with him. He told how Robert Vermillion, United Press reporter, tried to get out from under the debris and couldn’t. Said Vermillion, “Hey, somebody get me out of here.”

In France, Mr. Pyle finally saw all the death he could stand for a while. He wrote candidly that he could no longer take it. He had to come home.

Soldiers wrote him letters telling him they knew just how he felt, and they didn’t blame him.

But Mr. Pyle couldn’t stay away from a war that he felt was his as much as it was the Joes fighting it. So, he went to Okinawa.

In the Pacific he went aboard an aircraft carrier n Vice Adm. Marc A. Mitscher’s task force. He covered two naval air attacks on Tokyo in February and the invasion of Iwo Jima.

But he couldn’t stay away from the foot soldier, so he asked to be assigned to the Marines for the Okinawa campaign.

Before he departed, he had his belongings packed. He left instructions for their shipment if anything happened to him.

Went in with Marines

He went ashore at Okinawa with the 1st Marine Division. Then he went with an Army division to invade Ie last Monday. He watched the Doughboys move quickly ashore and capture the island’s three-strip airfield and gain control of the western two-thirds of the island.

It was as the troops pushed eastward to root out Japs dug in on the Iefusugu Mountain north of the town of Ie that Mr. Pyle was killed.

Everywhere he went, Mr. Pyle found fighting men looking for him. They told him their stories, and he always got their names and addresses right.

If he slept on the ground with a bunch of exhausted soldiers, he wrote a column about them in the morning. If the bombs came close, he told how the men took it.

Told everything

If they were hungry and dirty and homesick and grumpy and sick of war, he told about that, too.

Ernie’s columns about combat troops won them an increase in pay. He didn’t pretend to be a molder of opinion, he just thought that if airmen and others got extra pay for combat duty, the men with the rifles ought to get it, too. He said it would be good for their morale Congress agreed.

Mr. Pyle didn’t know any long words. At any rate, he never used them. He could write with great feeling and sharp discernment, with poetic feeling, even.

Loved by all

What he wrote hit a day laborer as hard as it hit a college professor.

The ordinary people loved him; witness the stream of letters-to-the-editor which flowed constantly into the newspapers which carried his column.

The learned also loved him, and showed him their respect. Witness the honorary degree bestowed upon him by his alma mater, Indiana University. They called the degree “Doctor of Humane Letters.”

Born in 1900 on farm

Ernie Pyle was born August 3. 1900, on a farm near Dana, Indiana. His father, William C. Pyle, still lives there. His mother, about whom he wrote from time to time in his column, died while he was in England in March 1941.

His full name is Ernest Taylor Pyle. Taylor was his mother’s maiden name.

He was married July 7, 1925, to Geraldine Siebolds, then a Civil Service Commission government clerk in Washington. She came from Stillwater, Minnesota. Mrs. Pyle lives in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where they built a home a few years ago.

Went to Indiana U

Ernie attended Indiana University for three and a half years and quit without graduating. He broke into the newspaper business on the La Porte (Indiana) Herald, then was moved to Washington, D.C., by the late Earl Martin, then editor of Scripps-Howard’s Washington Daily News.

He worked on The News from 1923 to 1926, when he was overcome by a yen for travel. He and “Jerry” drew out their savings, bought a Ford Model-T roadster, and the two of them drove clear around the rim of the United States in a leisurely way.

The trip wound up in New York, and Ernie worked as a desk man on The Evening World and The Evening Post for a year or two, until he was talked into returning to The Washington News as telegraph editor. There he worked up a terrific interest in aviation and started doing an aviation column on the side. It was a success and Ernie had an enormous acquaintance among airmen who are veterans of those days.

How column was born

He was made aviation editor of the Scripps-Howard Newspapers. Then in 1932 he was appointed managing editor of The Washington News.

Early in 1935, the Pyles took a vacation in Arizona. When they got back, the late Heywood Broun happened to be taking a vacation too, so Ernie wrote a dozen columns about his own vacation experiences to fill the Broun spot in The News. They made good reading and the eventual result was a decision by G. B. Parker, editor-in-chief of the Scripps-Howard Newspapers.

He and Jerry set out

So, Ernie and Jerry set out, by auto. The first of his columns appeared August 8, 1935, under a Flemington, New Jersey, dateline. He has been writing a piece a day ever since, except for an occasional timeout for rest.

Those early columns were leisurely copy, concerned with scenes and people and incidents encountered as he and Jerry drove around the country. He didn’t write “news.”

The Washington News ran the pieces regularly from the start, and has never missed one. Other Scripps-Howard papers gradually began using them, and eventually all were printing them as a fixed daily feature. The United Feature Syndicate began syndicating the column to non-Scripps-Howard papers.

Combed the continent

In those first few years Ernie, usually with Jerry traveling beside him, combed the United States, Canada, Mexico, Alaska, the Hawaiian Islands, Central and South America. He traveled by train, by plane, by boat, on horseback, muleback and by truck, but most of the time he drove a convertible coupe.

He spent several days at the leper colony on Molokai Island, went up the Yukon on a boat. flew to the Bering shore of Alaska, went down in mines and up on dams, drove from Texas to Mexico City before the famous highway was finished. He interviewed the great and the little.

His daily column contained human interest – whether whimsy or pathos, incident or personality. He eventually worked into it so much of his own personality that readers began to regard this stranger as an old friend.

Was in blitz

In 1940, Ernie went to England, and the blitz. Shortly after his arrival in London he went through the great firebombing during the holiday week of December 1940, and cabled home an account of “the most hateful, most beautiful single scene” he had ever witnessed.

Portions of the dispatch were cabled back to London and reprinted in London papers.

He spent some months in England and Scotland, and his dispatches from there were reprinted in book form.

Then he came back to the states for a rest. He was at Edmonton, Canada, preparing to shove off by plane over the new air route to Alaska, when word reached him that his wife was dangerously ill in Albuquerque. He flew to Albuquerque, and stayed with her for months until she recovered.

Just missed Pearl Harbor

Later he made all arrangements for a trip that would have taken him to Honolulu, Manila, Hong Kong and Australia. His clipper booking was cancelled to make room for propellers for the Chinese.

While he cooled his heels, this clipper arrived over the Hawaiian Islands during the Jap attack on Pearl Harbor.

In the early summer of 1942, he went to the British Isles, where he spent several months with our troops training in Northern Ireland and England.

Then came the invasion of Africa. He did not go in with the first wave, but arrived shortly thereafter.

Ernie spent much of his time living in the field with the troops. During the fighting in Tunisia, he went four and five weeks at a time without a bath, sleeping on the ground and on farmhouse floors, under jeeps and in foxholes.

Friends also killed

Many friends of Ernie’s have been killed in this war, including, aside from soldiers, Raymond Clapper of Scripps-Howard, Ben Robertson of The Harold-Tribune and Barney Darnton of The New York Times.

Ernie once wrote a friend:

I try not to take any foolish chances, but there’s just no way to play it completely safe and still do your job. The front does get into your blood, and you miss it and want to be back. Life up there is very simple, very uncomplicated, devoid of all the jealousy and meanness that float around a headquarters city, and time passes so fast it’s unbelievable. I didn’t have my clothes off for nearly a month, never slept in a bed for more than a month. It was so cold that my mind would hardly work and my fingers would actually get so stiff I couldn’t hit the keys.

Few of his readers knew it, but Mr. Pyle got a brief look at service life in the last war, although he never went overseas.

He enlisted in the Naval Reserve at Peoria, Illinois, on October 1, 1918. He was 18. He was released from active duty after the armistice but remained in the reserve and took a two weeks training cruise aboard the training ship Wilmette. He was honorably discharged on September 30, 1921, when the Navy cut down its reserve force for reasons of economy.

Mr. Pyle’s African dispatches were also published in book form.

In Sicilian invasion

Ernie was in on the invasion of Sicily, and soon after that came back to the states for a two-month rest. Then. he returned to the Mediterranean Theater, spent some months with the Fifth Army in Italy, and then went to England to await the invasion. He went into Normandy on D-Day plus one.

His column appeared in more than 300 newspapers, including the Army newspaper Stars and Stripes.

Ernie stayed in France through the battle of the breakout. He was almost killed by U.S. bombers at the time Lt. Gen. Leslie McNair was killed.

After the liberation of Paris, he decided he had “had it,” and came home for a rest in Albuquerque and a visit to Hollywood, where a film based on his experiences has just been completed.

He left early this year for the Pacific.

Gained wide honors

In 1944, Mr. Pyle was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for distinguished correspondence in 1943. He was voted the outstanding Hoosier of the year by the Sons of Indiana of New York. In October 1944, the University of New Mexico conferred on him the honorary degree of Doctor of Letters.

In November 1944, the University of Indiana conferred on him the honorary degree of Doctor of Humane Letters.

Sigma Delta Chi awarded him their Raymond Clapper Memorial Award for war correspondence in 1944. In both 1943 and 1944, he received a Headliner’s Club award.

Mr. Pyle’s third book, Brave Men, was the December 1944 selection of the Book-of-the-Month Club.

Dreaded going back

Lincoln Barnett, in an article in Life Magazine last month, said the G.I.s’ own war correspondent didn’t want to go back to the war – any more than any other man who braves death in the battleline.

“I dread going back and I’d give anything if I didn’t have to go,” Mr. Pyle told the author after his return from Europe. “But I feel I have no choice I’ve been with it so long I feel a responsibility.”

Ernie Pyle’s five-foot, eight-inch frame carried only 112 pounds. Despite his appearance of fragility, the sparse-haired little man lived with the fighting men, lived as they lived – and he died as they die.

Mr. Barnett wrote that:

Ernie has come to be envisaged as a frail old poet a kind of St. Francis of Assisi, wandering sadly among the foxholes, playing beautiful tunes on his typewriter. Actually, he is neither elderly, little, saintly or sad.

Extracts from article

Extracts from Mr. Barnett’s article follow:

Success thrust itself upon him… he cares nothing for the money it has brought, and is embarrassed by the fame… but he keeps going because he feels that he must.

Although Pyle is America’s No. 1 professional wanderer, he is fundamentally a sedentary person who likes nothing better than to sit in an overheated room with a few good friends. Sometimes he appears to find conversation less pleasurable than the simple circumstance of being seated.

His apparent agoraphobia is a byproduct neither of war nerves nor a swelled head. He has always been self-effacing, and he finds himself uncomfortable in his current eminence as the nation’s favorite war reporter, Pulitzer Prize winner and author of two bestsellers.

Not timid

He has been called shy, but he is not timid. His reticence is marked by quiet dignity.

He likes people as individuals and writes only nice things about those he mentions by name in his column, “But there are a lot of heels in the world,” he says, “I can’t like them.”

The Life article points out that Ernie has always been an apostle of the underdog. Seven years ago, after visiting a leper colony, he wrote that “I experienced an acute feeling of spiritual need to be no better off than the leper.”

“And so in war,” says Mr. Barnett, “Pyle has felt a spiritual need to be no better off than the coldest, wettest, unhappiest of all soldiers.”

The article relates that when Ernie gave his consent to the making of the movie, The Story of G.I. Joe, he stipulated that (1) the hero of the picture must be the Infantry and not Pyle; (2) that no attempt be made to glorify him, and (3) that other correspondents be included in the story.

The movie, in which Capt. Burgess Meredith plays Ernie, will be seen by troops overseas in June and be released to the civilian public in July.

Huge earnings

In spite of his refusal to capitalize on his fame when he returned from the European fronts, Ernie has made close to half of a million dollars in the past two years, Mr. Barnett estimates.

While he was home, he wore one suit, which he bought for $41.16 when he landed in New York. His home is a modest house in Albuquerque, which cost about $5,000. He puts his money into war bonds and, according to Mr. Barnett, quietly bestows substantial sums upon “friends, relatives, G.I.’s and anybody else he likes.”

Hundreds pray for him

The article continues:

Although Pyle disdains his affluence, he is keenly appreciative of the aureole of national esteem and affection that now envelopes him.

The emotions Pyle evokes in his public go beyond detached admiration. He is probably the only newspaper columnist for whom any notable proportion of readers have fervently prayed.

For some time after D-Day, 90 percent of all reader queries that came into Scripps-Howard offices were: Did Ernie get in safe?

His success has been achieved without much push on Emie’s part, the article maintains.

It declares that he took journalism at the University of Indiana because someone told him it would be an easy course.

Two years after going to Washington, Ernie married Geraldine Siebolds, an attractive girl from Minnesota who had a job with the Civil Service Commission. Later, when he became a roving reporter, she was known to millions as “that girl.”

He goes to war

“A small voice came in the night and said Go,” Ernie wrote in the fall of 1940. It was the same voice that had spoken to him in the leper colony in Hawaii. So, he went off to war.

Pyle’s first overseas trip in the winter of 1940-41 multiplied readers of his column by 50 percent. Stirred by the spiritual holocaust of London and his own relentless instinct for self-immolation, he produced columns of great beauty and power. But it was not until he reached North Africa the following year that the Pyle legend began to evolve.

The article tells how Ernie, afflicted by one of his periodic colds, remained in Oran while the other reporters went to the front. There he met some obscure civilians who told him about the turbulent political situation in North Africa and he scored an important scoop.

The Doughboys’ saint

Gradually, as he moved about among the soldiers, covering the “backwash” of the war, he became the patron saint of the fighting foot soldier, the article relates. But he didn’t know it for a long time.

He thought, when he wrote it, that his famous column on the death of Capt. Waskow was no good.

Ernie ‘singled out’ by Jap gunner

By the United Press

Ernie Pyle was “singled out” by a Jap machine gunner and was killed instantly while he was talking with an officer in a command post on Ie, Larry Tighe, Blue Network reporter, reported from Guam today.

Other reporters said there was the same kind of stunned disbelief at headquarters when the news of Mr. Pyle’s death arrived as when President Roosevelt’s death was announced.

Mr. Pyle was shot three times through the temple, Blue Network Correspondent Jack Hooley said. He added that Mr. Pyle was headed for the front with Lt. Col. Joseph Coolidge of Arkansas when a burst of fire sent them scrambling from their jeep into a ditch.

After a few minutes they peered over the edge of the ditch and the gun rattled again, Col. Coolidge ducked back to find Mr. Pyle dead beside him.

Col. Coolidge crawled to safety and three tanks moved up to rescue Mr. Pyle’s body. Steady machine-gun fire pinned the men inside the tanks and finally Cpl. Alexander Roberts of New York volunteered to go alone.

He found Mr. Pyle with the fatigue cap he wore “in safe places” clutched in his hand. A chaplain and litter bearer went forward and aided in taking the body within the American lines, Mr. Hooley said.

Roving Reporter

By Ernie Pyle

NOTE: This column by Ernie Pyle was part of his general running story of the battle of Okinawa, written during the campaign that led to his death. It is believed that other instalments were filed by him and will be received for publication.

OKINAWA (by Navy radio) – The company commander, Capt. Julian Dusenbury, said I could have my choice of two places to spend the first night with his company.

One was with him in his command post. The command post was a big, round Japanese gun emplacement, made of sandbags. The Japs had never occupied it, but they had stuck a log out of it, pointing toward the sea and making it look like a gun to aerial reconnaissance.

Capt. Dusenbury and a couple of his officers had spread ponchos on the ground inside the emplacement and had hung their telephone on a nearby tree and were ready for business. There was no roof on the emplacement. It was tight on top of a hill and cold and very windy.

My other choice was with a couple of enlisted men who had room for me in a little gypsy-like hideout they’d made.

It was a tiny, level place about halfway down the hillside, away from the sea. They’d made a roof for it by tying ponchos to trees and had dug up some Japanese straw mats out of a farmhouse to lay on the ground.

I chose the second of these two places, partly because it was warmer, and also because I wanted to be with the men anyhow.

Mustache trouble

My two “roommates” were Cpl. Martin Clayton Jr. of Dallas, Texas, and Pvt. William Gross of Lansing, Michigan.

Cpl. Clayton is nicknamed “Bird Dog” and nobody ever calls him anything else. He is tall, thin and dark, almost Latin-looking. He sports a puny little mustache he’s been trying to grow for weeks and he makes fun of it.

Pvt. Gross is simply called Gross. He is very quiet, but thoughtful of little things and they both sort of looked after me for several days. These two have become very close friends, and after the war they intend to go to UCLA together and finish their education.

The boys said we could all three sleep side by side in the same “bed.” So, I got out my contribution to the night’s beauty rest. And it was a very much appreciated contribution too. For I had carried a blanket as well as a poncho.

These Marines had been sleeping every night on the ground with no cover, except their cold, rubberized ponchos, and they had almost frozen to death. Their packs were so heavy they hadn’t been able to bring blankets ashore with them.

Our next-door neighbors were about three feet away in a similar level spot on the hillside, and they had roofed it similarly with ponchos. These two men were Sgt. Neil Anderson of Coronado, California, and Sgt. George Valido of Tampa, Florida (Incidentally there’s another Neil Anderson in this same battalion).

So, we chummed up and the five of us cooked supper under a tree just in front of our “house.” The boys made a fire out of sticks and we put canteen cups and K rations right on the fire.

Other little groups of Marines had similar little fires going all over the hillside. As we were eating, another Marine came past and gave Bird Dog a big piece of fresh roasted pig they had just cooked, and Bird Dog gave me some. It sure was good after days of K rations.

Several of the boys found their K rations moldy, and mine was too. It was the old-fashioned kind and we finally realized they were 1942 rations and had been stored, probably in Australia, all this time.

Making conversation

Suddenly downhill a few yards. we heard somebody yell and start cussing and then there was a lot of laughter. What had happened was that one Marine had heated a K ration can and, because it was pressure packed, it exploded when he pried it open and there were hot egg yolks over him. Usually, the boys open a can a little first, and release the pressure before heating, so, the can won’t explode.

After supper we burned our K ration boxes in the fire, brushed our teeth with water from our canteens, and then just sat on the ground around the fire, talking.

Other Marines drifted along and after a while there were more than a dozen sitting around. We smoked cigarettes constantly, and talked of a hundred things.

As in all groups the first talk is of surprise at no opposition to our landing. Then the talk drifts to what do I think about things over here and how does it compare with Europe? And when do I think the war will end? Of course, I don’t know any of the answers but we’ve been making conversation out of it for months.

The boys tell jokes, they cuss a lot and constantly drag out stories of their past blitzes and sometimes they speak gravely about war and what will happen to them when they finally get home.

We talked like that for about an hour, and then it grew dark and a shouted order came along the hillside to put out the fires and it was passed on and on, and the boys drifted away to their own foxholes or hillside dugouts, and Bird Dog and Gross and I went to bed, for there’s nothing else to do after dark in blackout country.

Tribute by Dewey

ALBANY (UP) – Gov. Thomas E. Dewey said today that the death of Ernie Pyle “is a great personal loss to this country and to American journalism.”

Indiana officials pay Pyle tribute

BLOOMINGTON, Indiana (UP) – President Herman B. Wells of Indiana University, who conferred the doctor of humane letters honorary degree on Ernie Pyle last November 13, spoke of the fallen war correspondent today as “an unexcelled interpreter of the minds and hearts of men in peace and in war.”

Wells said:

Ernie Pyle was an illustrious son of the Hoosier State and of Indiana University. The state and the university share with the men in the Army and Navy throughout the world the great loss which has come through his death.

He was a homespun Hoosier, a discerning reporter, an unexcelled interpreter of the minds and hearts of men in peace and in war, and an advocate of the rights of soldiers in the ranks.

INDIANAPOLIS (UP) – Gov. Ralph F. Gates of Indiana today described Ernie Pyle as “a fellow Hoosier who made a great contribution to his profession and to his country.”

Gov. Gates said:

His memory will live on in the hearts of all of us, and we will be ever aware of the great contribution he made to his profession and his country, and to the honor he brought to the Hoosier State.

Ernie’s father, Aunt Mary stunned at news of death

Neighbor hears news on radio and informs family on Indiana farm

DANA, Indiana (UP) – William C. Pyle, father of war correspondent Ernie Pyle, and the writer’s “Aunt Mary” – Mrs. Mary Bales – were stunned today by word of his death.

Mrs. Ella Goforth, a neighbor, said the aging relatives of the famed newspaperman received word from another neighbor woman who heard the news on the radio.

“They’re just not able to talk about it now,” Mrs. Goforth said in a phone conversation from the Pyle farm home, near the Indiana-Illinois state line.

“They’re not taking the news very well.”

Mrs. Nellie Hendricks, who lives across the field from the Pyle home, heard the first news of Ernie’s death. She ran across the field to tell the writer’s father and his aunt. Then they turned on their own radio and heard the news, according to Mr. Goforth.

She said:

Mr. Pyle had a letter from Ernie about two weeks ago. That was the last word they had from him. He told them he thought he’d be home sooner than he’d expected – but of course, he didn’t know about this.

Tribute from Time –

‘It will be a long time before Americans forgot Ernie Pyle’s war’

Wednesday, April 18, 1945

The following widely-quoted tribute to Ernie Pyle appeared in Time Magazine:

…He is the most popular of them all. His column appears six days a week in 310 newspapers with a total circulation of 12,255,000. Millions of people at home read it avidly, write letters to him, pray for him, telephone their newspapers to ask about his health and safety.

Abroad, G.I.’s and generals recognize him wherever he goes, seek him out, confide in him. The War Department and the high command in the field, rating him a top morale-builder, scan his column for hints. Fellow citizens and fellow newsmen have heaped honors on him.

Wrote of small people

What happened to Ernie Pyle was that the war suddenly made the kind of unimportant small people and small things he was accustomed to write about enormously important.

Many a correspondent before him had written of the human side of war, but their stories were usually about the heroes and the exciting moments which briefly punctuate war’s infinite boredom.

Ernie Pyle did something different. More than anyone else, he has humanized the most complex and mechanized war in history. As John Steinbeck has explained it:

“There are really two wars and they haven’t much to do with each other. There is the war of maps and logistics, of campaigns, of ballistics, armies, divisions and regiments – and that is Gen. Marshall’s war.”

War of common men

“Then there is the war of homesick, weary, funny, violent, common men who wash their socks in their helmets, complain about the food, whistle at Arab girls, or any girls for that matter, and lug themselves through as dirty a business as the world has ever seen and do it with humor and dignity and courage – and this is Ernie Pyle’s war. He knows it as well as anyone and writes about it better than anyone.”

One reason that Ernie Pyle has been able to report this little man’s war so successfully is that he loves people and, for all his quirks and foibles, is at base a very average little man himself.

Understands men

He understands G.I. hopes and fears and gripes and fun and duty-born courage because he shares them as no exceptionally fearless or exceptionally brilliant man ever could. What chiefly distinguishes him from other average men is the fact that he is a seasoned, expert newsman. His dispatches sound as artless as a letter, but other professionals are not deceived. They know that Ernie Pyle is a great reporter.

…In his unique way, he is almost sure to be a sort of national conscience. He may be that even if he is killed in battle. For if Ernie Pyle should die tomorrow, as well he may, it would still be a long time before Americans forgot Ernie Pyle’s war.

G.I.’s hardest hit by death of Pyle

Overseas veterans feel loss keenly

Wednesday, April 18, 1945

Ernie Pyle’s death was a shock to the nation, but it hit hardest the men wearing those overseas service ribbons.

Servicemen and civilians alike were shocked by the word of his passing today, but on Pittsburgh’s streets, in the USO canteen, in drug stores and in public buildings it was the man in uniform who felt the keenest loss.

Met him in Italy

Pvt. William McGonigal of Montgomery County sat in the Canteen and stared at the floor when he heard the news. Then he said:

I shook hands with him near the Volturno River in Italy. He wrote about our outfit making the crossing. He was the one correspondent everyone wanted to meet. There was something about him… always up there on the line with us…

Added Pvt. Keat P. Heefner of Mercersburg: “He was with my outfit in Normandy… He was tops. We looked forward to seeing what he wrote just as much as civilians did…”

WACs pay tribute

Near the Canteen, two WAC sergeants told how they felt:

“It’s the second tragedy in a week,” declared Sgt. Connie McKim, and her companion, Sgt. Mary Haumesser, added: “I always read his column. No one could have written better.”

Said Pvt. Kenneth Strouse of Lakeside, Ohio: “We all learned things about the Army from Ernie, things we never learned from the Army itself…”

“It’s just Ike losing another commander-in-chief,” asserted Pvt. John J. Kane, 711 Southern Avenue.

But it fell to Lt. E. M. Morgan, whose address here is the Downtown YMCA, to sum up the way the servicemen felt about Ernie Pyle: “He had a lot of guts.”

That was the reaction of Pittsburghers in high places and low as the news spread throughout the city and received a reaction of stunned disbelief.

G.I.’s lose spokesman

“The G.I.’s have lost their spokesman,” said Orphans Court Judge Alexander C. Tener. “His columns and books were unique literature of warfare. He was close to the heart of every loyal American.”

Attorney Oliver K. Eaton: “His death is one of the real tragedies of the war… There’ll never be another Ernie Pyle…”

Brought war into home

Director of Elections David Olbum: “He brought the war right into your kitchen…”

Frank Knox, police radio operator: “Through his columns I had a clear insight into the things my two boys are going through in Italy and Germany…”

Then there was “Richey,” the veteran “newsboy” at Liberty Avenue and Ferry Street, who was shocked at the news.

“It’s a tough blow to the readers who depended on Pyle,” he declared.

In Morals Court Magistrate W. H. K. McDiarmid declared Pyle’s death “a great shock to me, and a great loss to American journalism,” and Safety Director George E. A. Fairley added: “He was loved by the fighting men because he was not afraid to take the chances they took.”

‘National calamity’

“His passing is a national calamity. Ernie Pyle is just a household word. Everybody knows him,” said Collector of Interna! Revenue Stanley Granger, a veteran of the last war.

Another World War I veteran, Daniel Core, deputy clerk of U.S. Courts: “I think he gave us more insight into the life of a private soldier than any other correspondent has done.”

Weatherman William S. Brotzman, when told of Ernie Pyle’s death, exclaimed:

That’s a pity. He’s one of the best. He included so much in his stories – a good picture of the country, what the weather was like, what the boys were experiencing.

Knew trials best

Postmaster Stephen Bodkin said:

Ernie Pyle knew the problems and trials and tribulations of the doughboy perhaps better than any other person. I read him every day and read all his books. He was the war’s top-notch correspondent.

Judge Frank P. Patterson:

This dreadful war has brought us many tragedies, but none so personally shocking as the death of this fine reporter. He told the news as no other war correspondent did; he was a man who had the common touch. I, like everyone else, feel an overwhelming sense of loss in his passing.

“I think his loss will be felt deeply by the American public,” said Harry T. O’Connor, special agent in charge of the Pittsburgh office, FBI.

Clapper’s death in Pacific recalled

Pyle second killed on Scripps-Howard staff

Wednesday, April 18, 1945

When Ernie Pyle was struck down by a Jap machine-gun bullet on a little island off Okinawa, he was the second Scripps-Howard war correspondent to lose his life in those little-known places where this war is fought.

In February of last year, Raymond Clapper, who left the security of his Washington office to go to the Pacific theater, died in a plane crash during the invasion of the Marshall Islands.

Dots on a map

Okinawa… The Marshalls. Little dots on a map but the sites where brave men died as they tried to bring to the folks at home the bitter realty of war.

Ernie Pyle and Ray Clapper were great friends. Each had the ability to write for the man in the street, the woman in the home.

As Ernie put it in an article he wrote about his colleague in November 1940:

Ray Clapper, in his own mind, writes for the milkman in Omaha. He has come a long way from his own prairie days, but to him the milkman in Omaha is still America, and that feeling is probably what is making his column a great one.

Award to Pyle

Last May, the Raymond Clapper Memorial Award for distinguished war correspondence was given to Ernie Pyle by Williard Smith, president of Sigma Delta Chi, professional journalism fraternity. Already Mr. Pyle had been awarded the Pulitzer Prize.

Mr. Clapper was awarded posthumously the William Allen White Memorial Award.

Planes were taking off for the Marshall Island invasion, when Mr. Clapper was killed. He was in one piloted by a squadron commander.

As the planes were forming up to blast the Japs on their island strongholds, two collided. Both planes crashed in a lagoon. There were no survivors.

The words Mr. Clapper wrote from North Africa in July 1943 are particularly applicable to the deaths of two great correspondents.

“What appalls me about war is the unbelievable waste of life and effort and nature’s riches,” Mr. Clapper wrote.

Pyle wounded by Anzio bombs

Wednesday, April 18, 1945

Ernie Pyle almost lost his life on the Anzio Beachhead in March 1944, when German planes bombed a waterfront home he and other correspondents had taken over as their press headquarters.

Glider bombs wrecked the “Villa Virtue,” as the correspondents had named it, and Ernie was cut on the cheek by flying glass.

He was in bed when the planes came in to attack but he jumped up and began to cross the room to watch. He was blown back across the room by the first bomb, which struck about 10 yards from the building.

Three seconds later, as Ernie was picking himself from the floor, a second bomb crashed right beside the villa. The walls were blasted in, the ceiling crashed on Pyle’s bed and what remained of the villa was filled with thick dust and the acrid smell of explosives.

That wasn’t the only time Ernie Pyle ever was close to death, but thereafter he always referred to the incident as “my escape.”

Firing of Paris made Ernie sick of war

Wednesday, April 18, 1945

It was the bombing and burning of Paris by the retreating Germans last year which finally so sickened Ernie Pyle of war that he had to come home.

Interviewed in New York, he told why he had left the front.

He said:

It’s sort of hard to explain. I’ve been through plenty of bombings but when the Germans came over and pasted hell out of Paris soon after we got there, I suddenly knew that I had to get home and away from war. Seeing Paris burn really got me.

He returned on a ship bringing wounded soldiers.

He said:

They all wanted to tell me they understood why I was going back. I felt kind of funny. There I was physically unhurt, standing over those kids with arms and legs and eyes gone – all battered to hell – and they telling me they knew what the score was and that it was all right by them that I was getting out.

Pyle not dead – lives forever, senator says

WASHINGTON (UP) – Ernie Pyle’s senators paid tribute to him today.

Sen. Raymond E. Willis (R-Indiana) reminded the Senate that Pyle was born and reared in Indiana.

“Indiana,” Sen. Willis said, “is proud to claim Ernie Pyle as our noblest contribution to the cause of the preservation of freedom.”

Sen. Carl A. Hatch (D-New Mexico) from the state in which Mr. Pyle maintained his home – at Albuquerque – claimed him, too.

“Ernie Pyle is not dead,” Sen. Hatch said. “He was not killed by Japanese bullets. He shall live wherever the story of brave fighting men is told anywhere in the world.”

But though Mr. Pyle was born in Indiana and lived in New Mexico, he was claimed by everybody.

Everywhere in the Capitol, secretaries, elevator boys, policemen as well as lawmakers, were talking about Ernie Pyle. An elevator boy said: “You know, the servicemen would have elected him President.”

Pyle death shocks Aero Club head

Knew Ernie before he started rambling

Wednesday, April 18, 1945

The death of Ernie Pyle was a great shock to Clifford Ball, president of the Aero Club of Pittsburgh, and Mrs. Ball, who were intimate friends of the Pyles for 16 years.

Mr. and Mrs. Ball met Ernie Pyle and his wife Geraldine, or Jerry, in 1929 when they went to Washington on their honeymoon.

Became close friends

“Ernie then was aviation editor of The Washington Daily News,” Mr. Ball recalled. “I was arranging for an airmail line into Washington and he came to see me, bringing Mrs. Pyle with him.”

Started roving job

Mr. Ball said:

We became very close friends, like brothers and sisters. We visited each other for years and corresponded frequently.

This is how Ernie came to be a roving reporter. As aviation editor, he wrote human interest stories about people who fly. Then they made him managing editor and he stopped writing. When 18 out of 22 subscribers in one small community stopped the paper because he wasn’t writing anymore, the management decided to make a roving reporter out of him.

When he left for overseas the first time, he came here to get his outfit and Mrs. Ball went with him while he shopped.

The Pittsburgh Press (April 19, 1945)

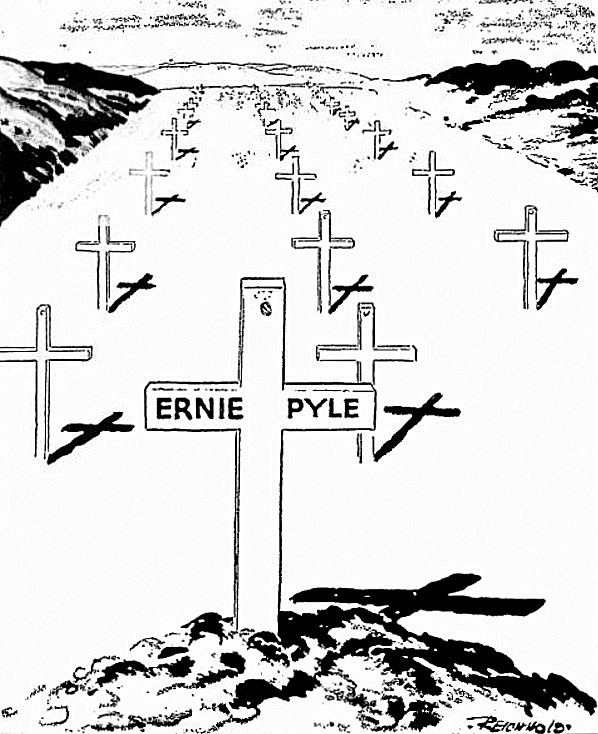

Pyle to rest among G.I.’s he loved

Writer to be buried in Army cemetery

By Mac R. Johnson, United Press staff writer

From the last two paragraphs of Here Is Your War, by Ernie Pyle, written after the African campaign.On the day of final peace, the last stroke of what we call the “Big Picture” will be drawn. I haven’t written anything about the “Big Picture,” because I don’t know anything about it. I only know what we see from our worm’s-eye view, and our segment of the picture consists only of tired and dirty soldiers who are alive and don’t want to die; of Jong darkened convoys in the middle of the night; of shocked silent men wandering back down the hill from battle; of chow lines and atabrine tablets and foxholes and burning tanks… and the rustle of high-flown shells; of jeeps and petrol dumps and smelly bedding rolls and C rations and cactus patches and blown ridges and dead mules and hospital tents and shirt collars greasy-black from months of wearing; and of laughter, too, and anger and wine and lovely flowers and constant cussing. All these it is composed of; and of graves and graves and graves.

That is our war, and we will carry it with us as we go on from one battleground to another until it is all over, leaving some of us behind on every beach, in every field… I don’t know whether it was their good fortune or their misfortune to get out of it so early in the game. I guess it doesn’t make any difference, once a man has gone. Medals and speeches and victories are nothing to them anymore. They died and others lived and nobody knows why it is so. They died and thereby the rest of us can go on and on. When we leave here for the next shore, there is nothing we can do for the ones beneath the wooden crosses, except perhaps to pause and murmur, “Thanks, pal.”

OKINAWA – Ernie Pyle will be buried among the soldiers he immortalized.

The beloved little war correspondent killed by a Jap machine-gunner yesterday probably will be laid to rest in an Army cemetery here in the Ryukyus where he covered his last campaign.

The soldiers he loved brought him back from the battlefield back to where the noise of the guns is distant and dull. They lifted his pint-sized frame from the ditch where he fell, victim of a sneak machine-gun ambush.

They put him on a litter, and crossed his arms, and then carried him back to the rear.

Jap jealous of prize

It wasn’t easy. That Jap machine-gunner seemed jealous of his prized victim. It was four hours after Ernie was killed before anybody could get to his body.

Cpl. Alexander Roberts, Army photographer from New York City, tried to get in to take pictures. He said every time anybody would try to enter the clearing where Ernie had been killed the gunner would open up.

Finally, Cpl. Roberts crawled into the clearing on his belly, pushing his camera ahead of him.

“Ernie’s face was not twisted in pain or agony,” he said. “He looked pleasant and peaceful. If there hadn’t been a thin line of blood at the corner of his mouth, you might have thought he was sleeping.”

Said he would get it

Ernie always said he would get it, that he had used up his chances. He said it again just before he landed with the assault troops on Okinawa. He told a public relations officer that he had a premonition about the campaign. And he said to another officer that he thought he would go back to the States “right after this one.”

Instead, he went from Okinawa to Ie Island because, as he told a friend, his premonition was “pretty silly as I’ve run into nothing hot yet.”

So he went on

So he went on – as he had gone from Ireland to North Africa, to Sicily, Italy, France and the Pacific – to get more stories about his beloved G.I.’s. He wanted to write about the Marines.

Erie was an old dough from the word go. He sweated and suffered with the doughfeet, shared their hopes, fears, and thrills – their lives. Today he shared death with them and it was believed he would be put to rest with them, in a G.I. Army cemetery.

Ernie would have liked that.

Ernie Pyle spent his last hours doing the job he had always done – gathering notes from G.I.’s for his columns, James MacLean, United Press correspondent, reported.

Detained by cold

A two-day-old cold had confined him to the sick bay of a transport and prevented him from landing with other correspondents in the assault waves on Ie until Tuesday. He spent that day interviewing soldiers and officers on the battlefield.

Wherever he went he was surrounded by G.I.’s who swarmed around him, forgetting the battle in progress. They tried to get him to autograph captured Jap money, American bills or invasion bills until their officers ordered the men back into position.

Milton Chase, 33, a correspondent for Radio Station WLW in Cincinnati, and a former staff member for United Press in Shanghai, said Ernie walked very carefully on Ie, because of his fear of landmines.

Mr. Chase said:

He told me that the weapon he hated worst – more than machine guns, shells or anything else – was “stumbling blindly into minefields because they explode before you can duck or take cover.”

I DARE SAY —

Ernie Pyle

By Florence Fisher Parry

…As I wrote these words, the news of Ernie Pyle’s death came in… And I find that I must scrap what I have written… No, death does not mean “utter and final defeat.” Not to this man, who walked its way as one marked for the dread rendezvous.

Now that the world has come, we are not in the least surprised. We see now that this man would not, could not, survive the thing that drew him back to it. Some deep compulsion sent him forth again, against his will, against all the overtures which creature comforts must have made to his tired body and more tired soul.

He was so tired; the sickness of battle had seeped into the very marrow of him. He did not want that last assignment, an assignment which no human being but himself would have had the heart to give him.

But he had to go.

Feeling the bony finger on him, he still had to go.

You have to live with yourself; and, you have to die with yourself. These are compulsions which are known only to the great, the selfless. Greater love hath no man than to lay down his life on the altar of such compulsion.

Through a glass darkly

He would have called himself a little man, an unimportant man. He did not take on stature as he grew in fame; he merely took on more humanity and humility. He did not value his life more; he valued it less and less, as it became more important to others. He never saw himself in the history books. Few great men are as great as that.

I think what made him so dear to so many was that he was frail and acknowledged that he was afraid. It gave the boys in battle a kinship with him. He admitted to the very fear that was in them; and so they got to believing that to be afraid was a common and natural thing, and not contemptible at all, nothing to be ashamed of. It gave them comfort. If he had done nothing more than that, he still would be a great man, immortal to the boys he understood so well and who will mourn him in a way peculiar and different from all other kinds of mourning…

I find myself thinking of verses in the Bible, verses that seem to sing of Ernie Pyle and all his modest brotherhood the world over.

Charity suffereth long, and is kind… charity vaunteth not itself, is not puffed up… seeketh not her own… thinketh no evil… beareth all things… endureth all things…

For now we see through a glass, darkly…

No longer darkly, Ernie…

How blinding clear it must be now to you!

Lt. Lucas: Ernie Pyle was great reporter because he was what he wrote

Columnist feared Okinawa campaign, death of others, not his, worried him

By Lt. Jim G. Lucas, USMC combat correspondent

WASHINGTON – A month ago, at Guam, Ernie Pyle told me he was afraid of the Okinawa campaign.

I knew what he meant. He wasn’t afraid of dying. He didn’t take that into account, he was afraid of the sight and smell of death – the other fellow’s death – and of the mess a bloody show can make of a man inside.

Later, when he wrote his first Okinawa story, he said that. He wrote he’d dreaded going ashore and stepping over dead men who’d come in alive. He said he was relieved not to find them.

Ernie was a great reporter because he was your reporter. He was writing for you. I had just come through Tarawa when I read his account of the death of the young Texas captain in Italy. To me, that was the finest prose ever written. I knew, on Tarawa, that Ernie Pyle, in Italy, had written that for me. It was something we shared together.

He was what he wrote

He was a great reporter because he was what he wrote. He didn’t think of himself as great. At Guam, he was distressed if the military singled him out for special favors. His whole attitude was that this was a lot of fuss about nothing. He’d much rather sit around and be one of the boys.

If you sat down with Ernie to talk about someone, he knew he wanted you.

If you sat down because he was Ernie Pyle, he was unhappy and uneasy.

The announcement that Ernie Pyle was coming to the Pacific caused a lot of excitement. Marines, privates to generals, wanted him. The boys who went to Iwo Jima were disappointed because he didn’t go along. They felt compensated because he was on a carrier off shore. But I heard many complaints because he wasn’t with them on the beach.

Friend wounded

When I flew out of Iwo Jima, I found Ernie at Adm. Nimitz’s press headquarters on Guam. I stopped to tell them about Sgt. Dick Tenelly, a 4th Division combat correspondent who once worked with him on the Washington Daily News. Dick was wounded early in battle. I told Ernie that Sgt. Tenelly might lose a leg.

It hurt him.

“God, I hope not,” he said. “Dick deserves better than that.”

He wanted to know how it happened. I couldn’t tell him much only that Sgt. Tenelly had been shot through both legs, and evacuated before I could see him. He told me about men he’d seen wounded in Europe, and what it did to him.

Scared to death

“I’m on the next one, you know,” he said. “I’m scared to death.”

I said he didn’t look scared.

“Did you ever see anyone who did?” he asked. “But I don’t sleep much at night thinking about it.”

He said he wanted to get “the feel” of the Pacific war, and that was the reason he was going with the Marines to Okinawa. It wasn’t because he wanted to get into any more trouble.

“The Marines want you along,” I said. “The boys on Iwo are sore because you weren’t there.”

“They’re a cheerful bunch,” he grinned. “Want to get me hurt, do they? I’m glad I wasn’t. That must have been a rough one.”

We assured him it was.

Made war real

You didn’t have to meet Ernie Pyle to know him. It helped, perhaps, but his gift was that he was able to leave something of himself in every piece he wrote.

They’ll bury Ernie in the Pacific, but he won’t be forgotten. I wish he’d been able to see more of the Pacific war. He wouldn’t have liked it – he’d have hated it bitterly – but he’d have been able to make a lot of others hate it with him. Because when he wrote of war, he made it real, perhaps because it was so real to him.

Chaplain, Marine brave Jap fire to get Pyle’s body

By Jack Hooley, Blue Network war correspondent

IE ISLAND (April 18) – Ernie Pyle died here on Ie Island at 10:15 in the morning. An hour later, word of his death had spread over open water as far as Mi Island, two miles away. Relayed by an artillery officer at the front by radio, by blinker light and by word of mouth, it had spread from Ie to the ships standing off shore – all in that short time.

The facts are quickly told. Ernie Pyle went ashore the evening before. In the morning, having heard that our troops were engaged in heavy fighting for a time below a mountain peak on the tiny island, he set out for the spot with Lt. Col. Joseph Coolidge.

The two men bumped along in a jeep over the narrow road taken by our troops the day before. As the jeep rounded a corner, a sudden burst of fire from a Jap machine gun hidden on a ridge sent both men scrambling for a ditch.

The gunfire stopped. Both had been through this kind of thing before.

Death came instantly

After a few minutes they peered cautiously over the edge. Another burst of fire and Col. Coolidge ducked back. He turned to Ernie.

The veteran correspondent lay on his back, too still for life.

Death had come instantly from three bullet wounds in the temple.

Every bit of movement brought a burst of fire from the hidden Japs, but finally Col. Coolidge managed to crawl to cover and submit his report.

Tank men helpless

For a long while, Ernie’s body was inaccessible. Finally, the chaplain of the outfit asked for volunteers to bring him in.

First three tanks moved up. Their appearance was the signal for the machine-gunner to open up with such a steady fire that the crew men were helpless inside the tanks.

When they retired, Cpl. Alexander Roberts of New York City volunteered to go alone. From the point beyond which the Yanks had retired about 125 yards back of the bend in the road, Cpl. Roberts crawled to the jeep.

He found Pyle’s face beneath the helmet he wore, peaceful in death. In his left hand, Ernie clutched the Marine fatigue cap he always wore.

Preferred cap

“A helmet is a lot of iron for a man like me to carry around,” he said to me recently, “so when I get to a safe place I switch to a cap.”

With the way shown by Cpl. Roberts, the chaplain, who had not wished to risk four lives, crawled over the ground with a litter bearer and they made 80 yards of the return trip before the machine gun opened upon them.

Four hours after his death, Ernie Pyle’s body was inside our lines again.

The boys in the lines out here were thrilled when Ernie Pyle came out to the Pacific. G.I.’s, Marines and youngsters on the ocean knew that he didn’t have to but they were glad he came anyway.

“We had waited for him so long,” said one of them today.

Editorial: Ernie

Newspaper people, we think, may be forgiven sometimes if they take advantage of their solitary medium of expression to speak out of their hearts about one of their own.

Our troubles, our losses, are not your troubles and your losses. They are our own. You, ordinarily, have no reason to be interested in them.

But, this once, we think you are interested.

You are interested because Ernie Pyle was as much of you as he was of us.

Ernie is dead. You don’t believe it. Neither do we. Neither do the G.I. Joes, nor the Navy Joes, nor the Marine Joes. Nobody believes it. But it is true.

Killed in action!

That was Ernie, all over.

![]()

He didn’t want to go. He had seen enough of war. Of its bloody form. Of its ultimate and inevitable terminus – death. Of its amazing horror. Of its gruesome catastrophe. Of its inhuman methods.

Ernie was scared. And he admitted it. He admitted his fright as no coward ever would do.

But he went.

He went because he had to go. Something drove him to go. Even as it has drawn every G.I. Joe. Every Joe who was a friend of Ernie. Every Joe to whom Ernie was an everlasting friend.

Ernie made himself go back to the war – after he had seen so much of it. After he had had so many close calls. Not for glory. He had enough of that. Not for money. He had that, too. He went – well, he had to go. Ernie was that kind of a little guy.

![]()

What we say about Ernie Pyle just makes so many words. What the G.I.’s say about him makes a memorial more fitting than any the greatest lyricist could pen.

He was one of them. Willfully, thoughtfully and, still, unconsciously, he was one of them. He couldn’t help it. He died one of them.

![]()

When Ernie went off to the Pacific, he wrote in his first column: “Well, here we go again.”

That was Ernie. Not wanting to go. Hating all that going meant. Yet feeling compelled to go.

“Here we go again.”

![]()

And soon after he got there – that is, in the Marianas – Ernie wrote about the B-29s. How they went off on their missions, knowing full well some never would come back.

“It is just up to fate,” he said. “But you cannot know ahead of time who it will be.”

The law of averages caught up to Ernie. He knew it would catch up, someday. But he went anyway.

“You cannot tell ahead of time who it will be.”

This time, God bless him, it is Ernie.

We can’t believe it. You can’t believe it. But – his number came up. That’s the way it is in war. It has been that way with thousands of Americans – level-headed, scared Americans, brave men. Men whom Ernie knew so well and typified so well. But it’s true.

![]()

Last February, when Ernie resumed writing, after a terribly earned rest, we said: “Something has been missing in the coverage of the war since Ernie had to come home for a rest.”

Now, something will be missing – forever.

Kate Smith broadcasts eloquent tribute to Pyle

NEW YORK – In her noon broadcast yesterday over the Columbia network, Kate Smith paid the following tribute to the late Ernie Pyle, famed war correspondent:

The nation which lost its leader less than one week ago has a new grief to bear this noon. For only a short time ago, the Navy Department announced that Ernie Pyle, beloved war correspondent and friend of every G.I. Joe, has been killed in action.

Died in harness

Like his Commander-in-Chief who fell last Thursday, Ernie died in harness. He was struck down by enemy machine gun fire on a little island off Okinawa. He was right up there in the front line, as always. Sweating it out with the fighting men, in the thick of battle doing the same magnificent job that he has done ever since America went to war.

United States soldiers, sailors and Marines have lost a staunch friend in the death of Ernie Pyle. He was their champion and their hero.

Suffered with men

The bald little reporter had lived and suffered with American fighting men through months of bitter fighting in North Africa, Sicily, Italy and France. He came home after those campaigns, simply, he said, because he couldn’t bear the sight of death any longer.

But it wasn’t long before he was off again, this time to the Pacific. Ernie Pyle followed the call of duty. He felt he owed it to America’s fighting men to support their valiant conquests in the Pacific. And there he met the death he had been close to so many times before.

Truman expresses sentiment

President Truman spoke these words a moment ago, and they speak the sentiments of every American who knew Ernie Pyle through his human, realistic accounts of the war. He said “no man in this war has so well told the story of the American fighting man as American fighting men wanted it told. More than any other man he became the spokesman of the ordinary American in arms.”

“Nobody knows how many individuals in our forces and at home he helped with his writings. But all Americans understand now how wisely, how warmheartedly, how honestly he served his country and his profession. He deserves the gratitude of all his countrymen. God bless him. May he rest in peace.”

G.I. preview for Pyle film

Movie’s release due in July

By Maxine Garrison, Press Hollywood correspondent

HOLLYWOOD – The death of Ernie Pyle will bring no changes or additions to the film, G.I. Joe, based on the famous war correspondent’s frontline reportings.

Lester Cowan, producer of the movie in which Burgess Meredith portrays Mr. Pyle, said that the completed film will be shown first to troops on Okinawa – the self-same men who were Ernie’s “buddies.”

The film will not be released to the public until July, Mr. Cowan said.

Roving Reporter

By Ernie Pyle

In addition to today’s column, we will print several others which we have just received from Ernie on Okinawa. We believe he would have wanted it this way.

OKINAWA (by Navy radio) – That was one of the most miserable damn nights out of the hundreds of miserable nights I have spent in this war.

Bird Dog and Gross and I turned into our sacks just after dark. So did everybody else who wasn’t on guard. It was too early to go to sleep, so we just lay there in the dark and talked. You could hear voices faintly all over the hillside.

We didn’t take off our clothes, of course; nobody does in the field. I did take off my boots but Bird Dog and Gross left theirs on for they had to stand watch on the field telephones from 1 till 2 a.m.

The three of us lay jammed up against each other, with Bird Dog in the middle. We smoked one cigarette after another. We didn’t have to hide them under the blanket for we were in a protected position where a cigarette couldn’t be seen very far.

Like flamethrowers

Right after dark the mosquitoes started buzzing around our heads. These Okinawa mosquitoes sound hike a flame thrower. They can’t be driven off or brushed away.

I got a little bottle of mosquito lotion out of my pocket and doused mv face and neck, though I knew it would do no good. The other boys didn’t even bother.

Suddenly Bird Dog sat up and pulled down his socks and started scratching. Fleas were after him. Even the grass has fleas in it over here!

For some strange reason I am immune to fleas. Half the boys are red welted with hundreds of itchy little flea bites, but I have never had one.

Choice mosquito bait

But I’m the world’s choicest morsel for mosquitoes. And mosquito bites poison me. Every morning, I wake up with at least one eye swollen shut.

That was the way it was all night, with all of us – me with a double dose of mosquitoes, all the rest with a mixture of mosquitoes and fleas. You could hear Marines hushfully cussing all night long around the hillside. Suddenly there was a terrible outburst just downhill from us and a Marine came jumping out into the moonlight, cussing and jerking at his clothes.

“I can’t stand these damn things any longer,” he cried. “I’ve got to take my clothes off.”

We all laughed under our ponchos while he stood there in the moonlight and stripped off every stitch, even though it was very chilly. He shook and brushed his clothes, doused them with insect powder and then put them back on.

This unfortunate soul was Cpl. Leland Taylor of Jackson, Michigan. His nickname is Pop, since he is 33 years old.

Pop is a “character.” He has a black beard and even in the front lines he wears a khaki overseas dress cap which makes him stand out.

After Pop went back to bed, everything became quiet for several hours, but hardly anybody was asleep. The next morning the boys on guard said Pop must have smoked three packs of cigarettes that night. It was the same way with Bird Dog, Gross and me.

All night without even raising our heads we could see flashes of the big guns of our fleet across the island. They were shelling the southern part and also shooting flares to light up the front lines in the south.

Watch shells in flight

There were times when we could actually see red-hot shells, traveling horizontally the whole length of their flight, 10 miles away from us, and then see them explode.

Every now and then throughout the night our own company’s mortars were called upon to shoot a flare over the beach behind us, just to make sure nothing was coming In.

Once there was a distinct rustling of the bushes in front of us. Of course, the first thing I thought of was a Jap.

But then I figured a Jap wouldn’t make that much noise and finally I decided it was one of the houses the mortar boys had commandeered, crashing through the bushes. And that’s what it turned out to be.

Along about 4:30, I guess we did sleep a little from sheer exhaustion. That gave the mosquitoes a clear field. When we woke up at dawn and crawled stiffly out into the daylight, my right eye was swollen shut, as usual.

All of which isn’t a very war-like night to describe, but I tell it just so you’ll know there are lots of things besides bullets that make war hell.