Casey: A dead Nazi’s pictures bare war tragedy

Captured La Haye an awesome sight

By Robert J. Casey

On the U.S. front in Normandy, France –

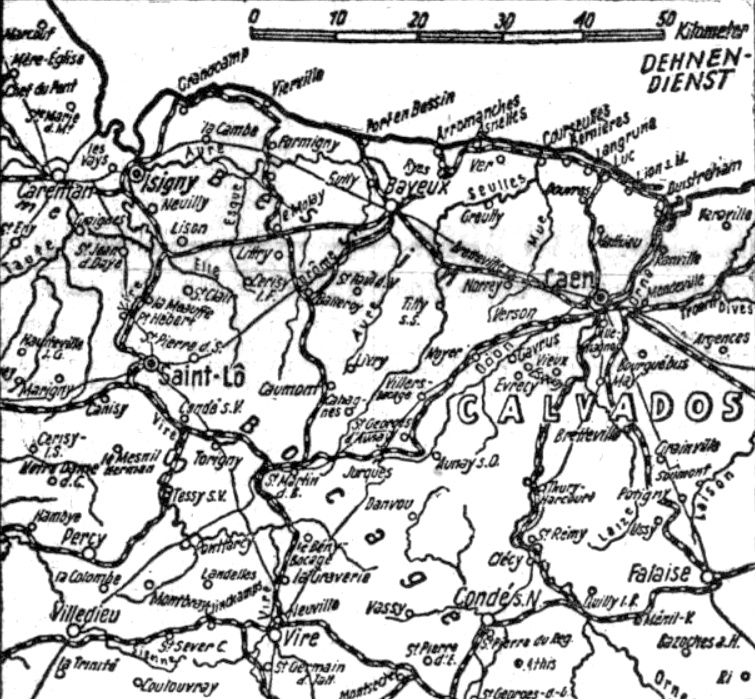

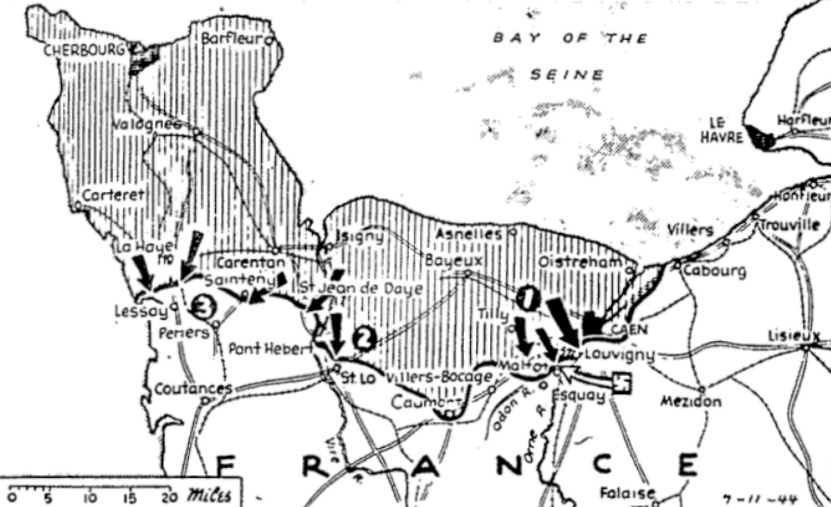

South of La Haye-du-Puits, U.S. troops today were slowly blasting through more hedges, stone walls and ranks of unconvinced Germans on their way to the promised land of flat country where a man has a chance to see what he is fighting.

The weather, as usual, was rotten and mud thick and plentiful in fields and roadways, and the going was still tough and dangerous from one end of the line to the other, but when various corps spokesmen announced that “progress was satisfactory” you felt inclined to believe them.

Town a terrible sight

We got into La Haye in force yesterday morning and crashed through the principal defenses at the railroad station. To one who had looked at it across the lovely valley in the British sun of five years ago, the town was an awesome and terrible sight.

There was no charm about it now. Snipers were still sending out venomous fire from skeletons of rooftops. Rocket guns – “screaming meemies” – were dropping their howling slugs promiscuously from some concealed spot in orchards south of the town. The infantry moved about close to the battered walls, with heads well down and necks pulled in.

The ditches leading into the town were cluttered with German dead. Along hedgerows, turned over clear of the road, was a procession of the skeletons of burned and tortured trucks.

At the end of a side street under a tree, a dead German lieutenant, whose name had been Franz Ritter, lay grazing sightlessly into the rainy sky. Around him were scattered belongings that probably had been loose in his pockets when he fell – his paybook, military identity card, certificate of good standing in the Nazi Party, and a collection of snapshots, mostly of himself.

An American doughboy cradled his carbine under his arm and picked up some of the photographs. Looking through them, he said:

You can tell a lot about this guy from these. Look, here he is as one of those mugs in the Youth Movement.

He held out a picture of Franz in socks, shorts and military shirt, a sour-faced boy of about 17.

That’s about the time he started listening to this Hitler. And here he us as a member of the labor battalion.

Arrogant expression

That picture showed him in front of a barracks, leaning on a shovel and looking on the world with the same arrogant expression that now was frozen into his face by death.

And here he is as an officer, a bright new shavetail with a swastika on his arm. I suppose the whole world was his that day. All his folks were sending him congratulations and maybe presents.

The doughboys turned the picture over. There was a date on it: Feb. 17, 1944. That, as the doughboy said, probably had been the greatest day in the life of Franz Ritter, the Hitler Youth, the eager young laborer, the stiff-necked soldier of the Reich, the arrogant lieutenant. And on that day, he was less than five months from July 9 and only a few hundred miles from the muddy slopes of La Haye-du-Puits – a town of which he probably had never heard.

The doughboy bleakly said:

He’s had some hard luck, but you can’t say he didn’t ask for it. He was a Nazi and he was a sniper.

He laid the pictures back in a neat pile where he had found them and turned away. Franz Ritter continues to stare up into the rain.