By John Gunther, North American Newspaper Alliance

With the British 8th Army in Sicily, Italy – (July 28, by wireless, delayed)

Anyone who thinks Sicily is a green verdant isle should visit this sector of the Catania front where the Germans are fiercely resisting tried British troops. Perched on a cropped hilltop 1,000 yards from the enemy lines, we can survey a broad arc embracing almost all of the Catania plain.

As far as the eye can see, there is not a single spot of green and not a sign of water. The dusty fields have been harvested. They are covered with dry, tawny stubble that looks like Nebraska during a heat wave.

I asked an officer at headquarters in a deserted barn where we were. He replied:

We aren’t anywhere. This is a point on a map, nothing more.

The Germans up here are attempting infiltration tactics at night. They cross no man’s land in small groups, get among or behind British advance guards and try to toss grenades or shoot up posts with Tommy guns and then retreat into the darkness. Some of these enemy raiders speak English. They call out in good Oxford accents:

Sergeant major, who goes there? What unit is this?

They hope to get information this way, but they don’t often get it.

Main enemy position

The German defenses appear threatening in this particular area which I reached after a long tour of the front. It is one of the enemy’s main positions.

One officer told me:

I should call the situation rather stationary from the big point of view but we certainly are kept busy.

He described a British battalion which was isolated for 23 hours. It could not be relieved; no supplies could be sent up and nobody could be evacuated except a few men who were seriously wounded. Violent German shellfire prevented relief units from reaching the battalion.

An officer with a ripe Scottish accent commented:

It was a hellish business, mark you. Our troops in this sector are being carefully rested before new operations begun. In this kind of fighting, a man is virtually useless after eight or ten days in the frontlines. He must be given a chance to recuperate and replenish his energy.

British exposed on plain

So, the general lull and stalemate continues with the British pecking away and maintaining steady pressure but not yet attempting a full offensive. As in other areas of this general front, the enemy has cover on high ground whereas we are exposed in the plain below.

German reinforcements are believed still pouring in. The British are tired, largely because of the intense, pitiless heat and the lack of sleep. They didn’t get much sleep at night because German artillery keeps busy and infiltration parties cause confusion.

This is not like the desert. Digging in is very difficult because of the stubborn, stony nature of the ground. By day, rest is almost impossible because there is no shade.

An officer said:

My men are shag tired, that’s the word for it, shag tired.

A group of us manage to spend an hour swimming at a beach near Catania nearly every day and we see some remarkable sights from the waterfront. Those elegant folk accustomed in former days to loll lazily on the Mediterranean beaches should get a quick eyeful of this one. It is not merely a beach with a fine aquamarine water, but it is also a perfect ringside seat for one of the most striking shows on earth.

Find ‘chutist’s grave

We first got the idea that swimming at the beach had unusual elements when – the first time we were there – our conducting officers happened to find a couple of grenades lying around. They thoughtfully exploded them and tossed them aside. Next, we saw a grave of an unidentified British parachutists a few yards from the pellucid surf. He had been buried where he fell presumably in the first landings. His parachute gear was set up in a kind of tombstone.

Then it became apparent that we had accidentally stumbled on a sheltered cove which commands an absolutely clear view of German-held Catania, a few miles away. We saw Spitfires rolling in nice decision patterns above the town and we poked through long reeds along the shore, wondering how close Nazi patrols were.

Battle of Sicily war writer’s dream

By L. S. B. Shapiro, North American Newspaper Alliance

With the Canadians in central Sicily, Italy – (July 24, delayed)

A dramatic change took place this afternoon in the shape of the battle for Sicily.

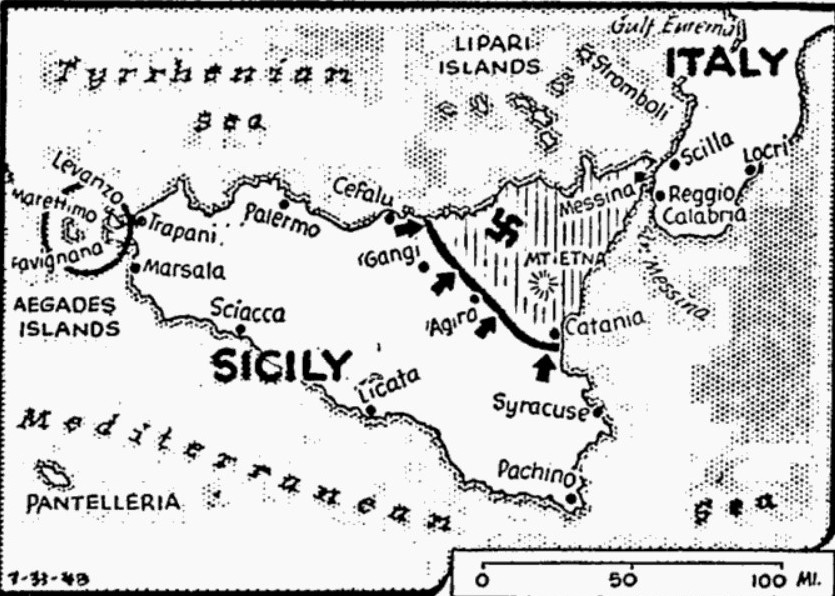

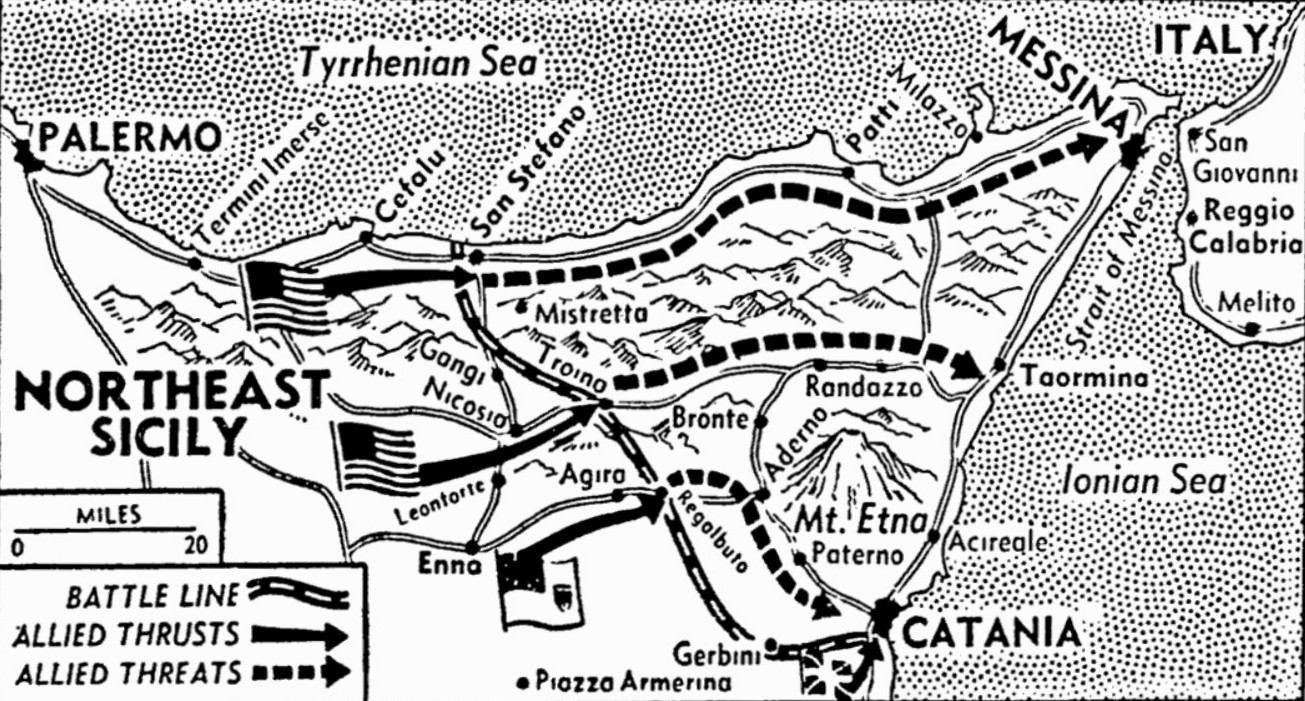

After advancing northwest for 100 miles from the Pachino Peninsula in 14 days, the Canadians suddenly wheeled right from the central part of the island and moved due east in a flareup of the most spectacular fighting they have experienced in the campaign.

Resembles Tunisian campaign

Gen. Alexander’s plan of campaigning naturally cannot be revealed but as I stood on a mountain top this evening, I watched the Canadians moving eastward, battling fiercely for a town and later fanning out toward the mountain top. The direction of the Canadians was easily visible from my point of vantage.

Beyond the rolling foothills of Mt. Etna, the famous mountain itself hung like a shimmering backdrop in the heat haze of a blazing day. Beyond the gun muzzles of the Canadians is Mt. Etna and eight miles beyond that lies the sea.

On the south side of the mountain, the British are developing a situation comparable with the next final stages of the Tunisian battle. The Germans are steadily being pushed back into the northeast corner of the island and the Allied forces are converging on the enemy’s defenses perimeter.

Maps hardly necessary

This campaign is a war correspondent’s dream. From commanding mountain tops, an observer can see not only the complete battleground, including the artillery of both sides and movements of tanks and infantry, but also the final objective of an advance.

Allied planes supporting the attack swooped down to the level of my vantage point and beyond loomed Mt. Etna, the south side of which I saw a few days ago while observing the battle for the Simeto Bridge. Printed maps are hardly necessary in this campaign, for each mountain top affords a view of a natural relief map.

Today’s action started promptly at 3 p.m. when the biggest concentration so far in the Sicilian campaign opened up suddenly against the German positions. War correspondents had been advised in advance and early in the afternoon I drove up the mountain to the observation post.

Allied air force strikes

This town is protected by sheer cliffs which were conquered by the Canadians last Tuesday (July 20). My jeep had difficulty in managing the terraced road to the town. It was full of sharp hairpin turns and we were eating our own dust all the way, I finally went the last lap on foot, climbing the cobbled streets built for mule traffic until I reached the topmost peak, crowned by an ancient turret reputedly built by the Normans.

From here the entire battle scene lay before me. After 45 minutes of creeping artillery barrage, a Canadian regiment advanced behind tanks.

At this point, the Allied air force swept over the German positions. I counted 50 planes in five minutes, and probably there were many more. Meanwhile, the Canadian artillery got the range of the German posts and our troops swept through.

I saw the flash of a German anti-tank gun, followed in a minute by a heavy explosion at the same point. The German gun was silent from then on.

As darkness fell, the Canadians had cleaned up and were advancing toward frightening heights guarding the approaches to the east. The hardest part of the battle remained for the hours of darkness. The Canadians were scaling cliffs which made the cliffs of Québec City look like curbstones and Gen. Wolfe’s storied victory seem like a second-class affair.

As I write this by the light of a curtained military truck the valley below is dotted with burning tanks and other vehicles. Shells are still screaming across the valley with a sound not unlike Benny Goodman’s top note. Canadian troops are still pouring into the valley. Tomorrow’s dawn will have a bloody story to tell.