Wolfert: Yanks’ plea for surrender creates havoc in Nazi line

Men who made it in the dark describe how they connived to escape and give up

By Ira Wolfert, North American Newspaper Alliance

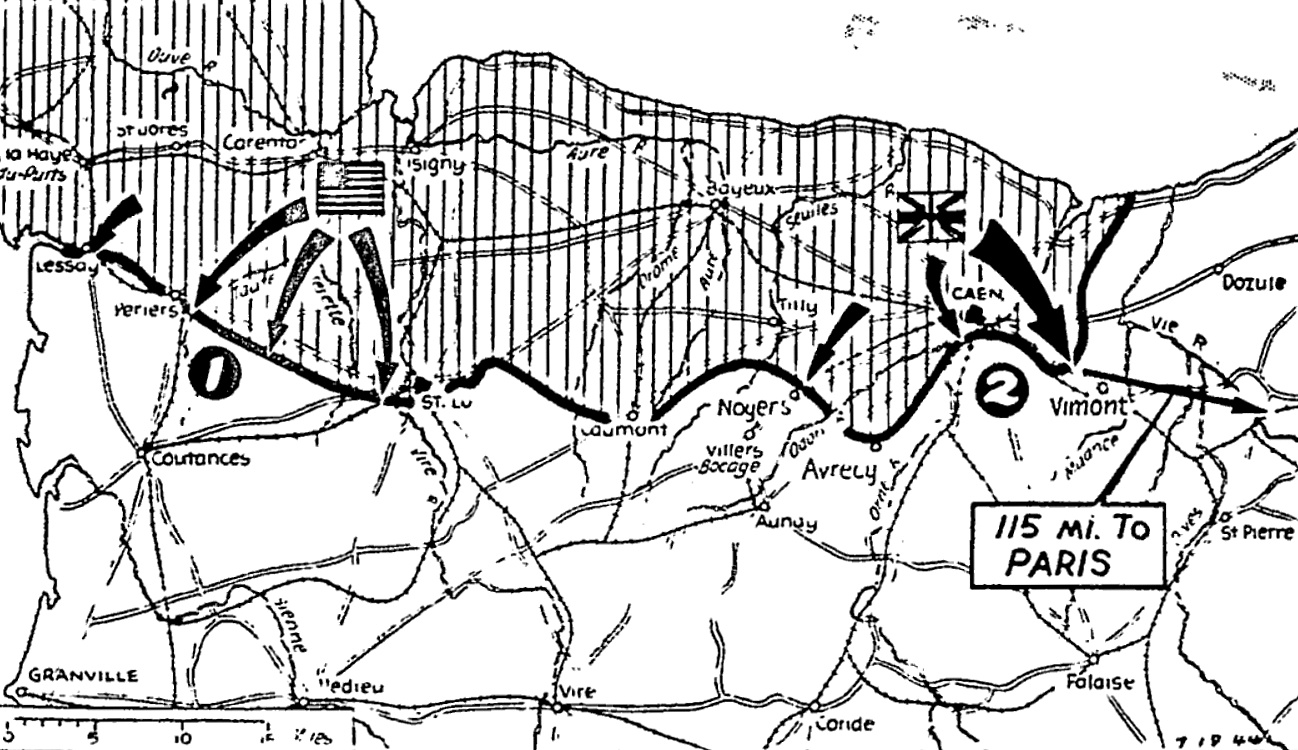

With the U.S. infantry outside Saint-Lô, France – (July 14, delayed)

The story of what happened in the German lines here as the result of what seemed to us an abortive propaganda broadcast was told by three German prisoners who gave themselves up on account of it.

One was a sergeant-major, a professional soldier with 15 years’ experience, whose tank calls for a regimental or at least a battalion command post but who has been serving as a platoon leader in place of second and first lieutenants lost by the Nazis in Russia. Another was a corporal of Carlsbad, a Nazi who was but eight years old when Hitler first came into power, and the third was a private who had also been educated only by Hitler.

The corporal and private were serving together at the time of the broadcast and the sergeant-major was commanding his platoon in another part of the lune. The corporal said his commanding officer, a Prussian about 25-year-old, kept shouting throughout the broadcast that anyone who listens to this broadcast will be shot. At the same time, the adjutant was on a telephone calling for artillery fire against the broadcasting van and loudspeakers.

Nazis fire on own men

As soon as the broadcast ended, eight men made a break for the American lines from foxholes and the commanding officer ordered machine guns to open up on them. The machine guns were fired and the eight men fell flat, whether to protect themselves or because they were killed is not yet known.

During the day, the corporal said the whole company took advantage of the times when their commanding officer was busy elsewhere to talk of the broadcast and of means of surrendering. It was suggested that somebody kill the commanding officer and then the whole outfit would walk over in body. But there was no one with the courage to start that kind of mutiny and, anyway, American fire on the position there was so heavy and fairly constant, that everybody was afraid to get out of his hole during the course of the day.

Men killed in holes

American sharpshooters killed three men in their holes and American mortars wounded three others.

The German corporal told only his buddy of his plans, he said. He was going to wait for darkness and then try to make it to the American lines.

The American broadcast had promised them good treatment if they came over, and they certainly were not getting good treatment from the Americans where they were. His buddy said he wouldn’t take the chance. If their own soldiers didn’t kill them in the darkness, then the Americans would.

Buddy follows along

About 1 o’clock in the morning the corporal lifted himself out of his foxhole and started running. His buddy, seeing him go three or four paces without being struck dead by the omnipotent Hitler, scuttled after him.

The corporal told me:

There was a burst from our machine guns, first once, then twice more, but I kept on running. I broke through a hedge then, and there was a little field ahead with dead animals in it and some dead soldiers. I fell over one but I don’t know whether it was German or American. It was too dark then to tell. There was another hedge and road, and still another hedge, then Americans.

They said, “Hends hop,” to me.

Story confirmed

His buddy confirmed the story in every detail. Every company has its diehard Nazis who can’t hope to live if they lose the war and these men will continue firing their weapons until they are killed.

The platoon leader hadn’t heard the broadcast. He has been busy in a hole with the wounded but he knew his men had had something to think about all day besides their duties, he said.

Finally, at 5 o’clock in the afternoon a friend, a sergeant, whispered to him cautiously about the broadcast. The sergeant-major agreed it might be a good idea to surrender but he did not confide his idea to the platoon. He seems to have been afraid the diehard Nazis in it might kill him, or even that some of the men who were afraid to surrender, would stay where they were and spoil his plans in order to ingratiate themselves with higher officers who would give them jobs in the rear.

The sergeant-major told only the sergeant what he wanted to do. The sergeant told another man he trusted, who told a third and so on down the line.

In all of the 35 men in the platoon, there were only seven who could be trusted. These seven said they would wait for the sergeant-major to make it and if he made it safely, then he should signal them and they would follow.

He made it safely but what happened to the seven others is not known here. If they responded to the signal, then perhaps they were killed doing so.

Shapiro: Strong men after battle weep like little children

Their hands shake, and they have to be aided to walk, but they will get all right

By L. S. B. Shapiro, North American Newspaper Alliance

With the British forces in Normandy, France – (July 26, delayed)

This is an ugly story. It may not make pleasant reading and yet it should be written because it is as much a part of the war as a great battle filled with brave incidents.

Indeed, you cannot know what until you have moved, as I did this morning, to a field clearing station behind out advancing battle line between the Odon and Orne Rivers.

The reception tent was empty when two British soldiers were brought in, bolstered by the arms of two ambulance drivers. They were ragged and all one could see on their mud-stained faces were saucer-like eyes staring straight ahead.

One was a slight man who wore spectacles and had blond hair. The other was a dark, rugged man with a fine head and a great pair of shoulders. They seemed not to be wounded, but somehow their legs weren’t working and they were almost carried to canvas chairs in opposite corners of the tent.

Weep like children

There they wept hysterically, and their choking sibs made them sound curiously like nursery children.

An orderly pulled up a chair beside the blond-haired soldier and talked rapidly into his ear, at the same time stroking his back. His sobbing ceased somewhat and the soldier rubbed his hands feverishly over his face, then turned to look at the orderly.

He opened his mouth, but nothing audible came to his lips. Then he put his face into his cupped hands and wept again.

The orderly lifted the soldier’s head and pushed a cigarette between his lips. But before a match could be applied, the cigarette fell to the ground.

Hands shake

Again, the orderly patted his back, lit the cigarette himself and placed it in the soldier’s mouth. The younger puffed feverishly, and smoke drifted out of his nostrils and made him cough. He mumbled some inaudible words and his hands shook so desperately that the orderly grasped them and held them tightly.

On the other side of the tent, the dark, rugged soldier was being helped to his feet by a doctor. Together they began walking toward the exit, the hefty soldier stumbling along like a baby learning how to walk.

The blond, slight man watched them pass and his eyes followed them across the tent and out into the open, and a flicker of a smile played on his quivering lips as though he were amused by such helplessness on the part of the other soldier.

He seemed normal for a moment, then suddenly the cigarette dropped from his lips and his hands pawed at his cheeks and eyes and he wept hysterically.

The doctor returned to the tent and looked at him.

He whispered to me:

Battle exhaustion. The boy has been under shell and mortar fire for six days in exposed positions. We will put them to sleep for a couple of days and they’ll be all right.