THE NEWS OF THE WEEK IN REVIEW

Zero hour

‘The Battle of Europe has begun’

The invasion begins

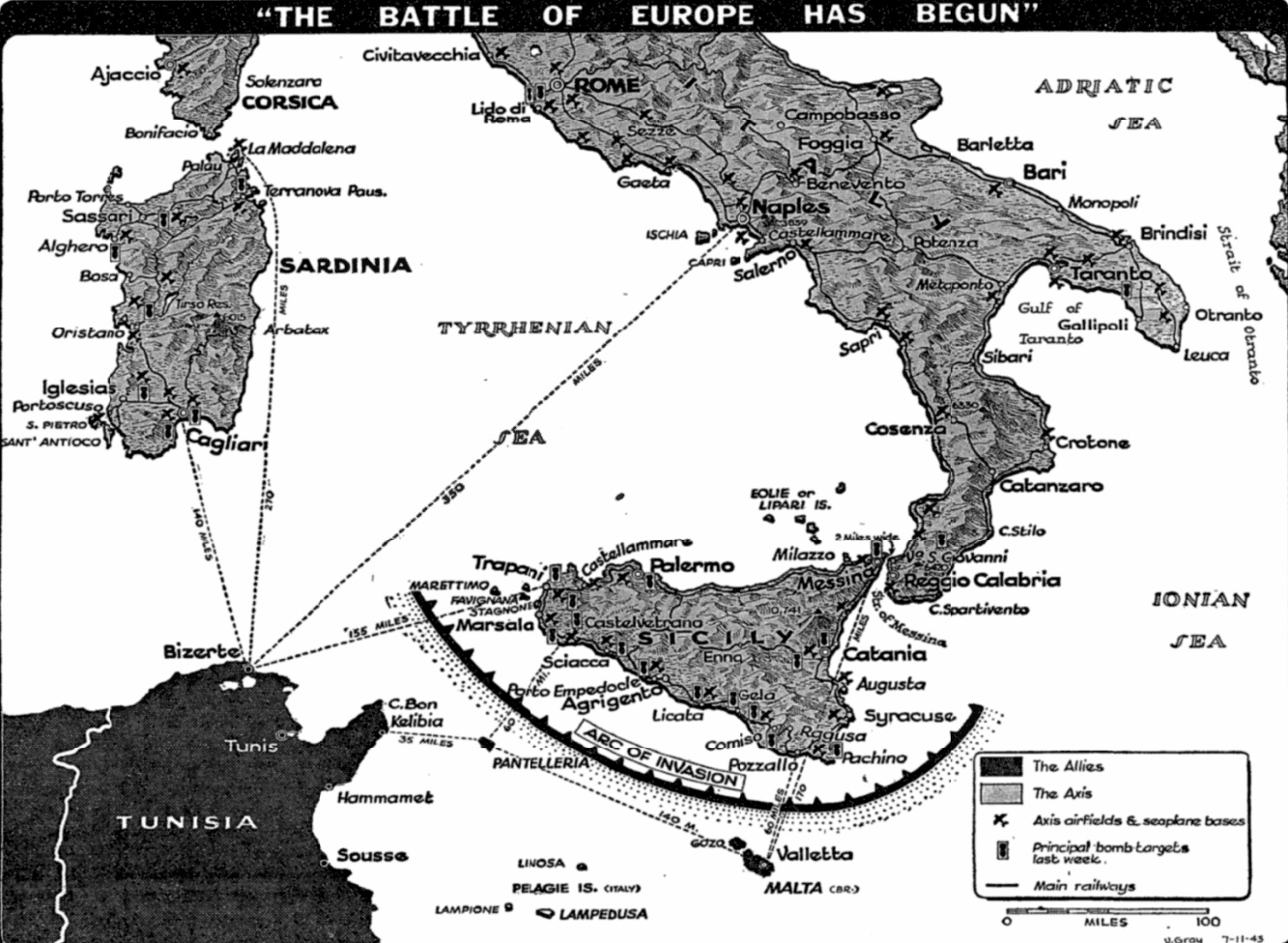

At 3 o’clock yesterday morning the Battle of Europe began. The second front was opened. The moment which the Allied world had long awaited came with dramatic suddenness in the dead hours of a moonlit Mediterranean night. From North Africa to Sicily moved thousands of Allied troops that have for months been in training for the initial assault on the fortress Hitler has made of a continent.

The invasion forces came by sea and air. Over the quiet waters steamed big transports, snub-nosed, shallow-draft invasion barges, powerful warships of all kinds. Above them were big troop-carrying planes guarded by fighters. In minutely timed coordination the Allied forces swept ashore or dropped from the skies to assault the tightly drawn defenses of the Italian island. A naval barrage and days of aerial attack had helped to clear the way. But the ultimate task was one for fighters on foot – man-to-man combat of the toughest kind.

Allies in action

It was truly an Allied attack. The bulk of the assault forces that had been gathered in North Africa were made up of British, Canadian and U.S. troops. But there were also Polish, Czech, Yugoslav and Greek units and large French contingents. In all – the Axis reported – there were more than a million United Nations fighters assembled. The Allies made no statement, but Berlin dispatches said there were 44 infantry divisions, 15-20 armored divisions, at least 4,000 airplanes of all kinds, “a considerably strengthened” naval force and two full divisions of parachute troops.

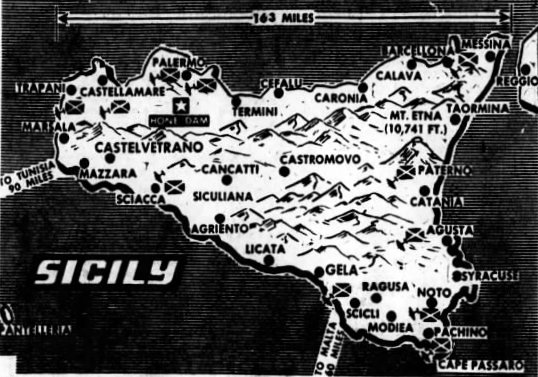

Their objective was one of Hitler’s most important bastions. Sicily is the largest island in the Mediterranean. It is Italy’s second largest “compartimento” – department – in terms of area, third largest in population. Until recently more than 4,000,000 people lived in its 9,926 square miles. Many thousands are reported to have been evacuated in the face of the Allied invasion wheatfields, hillside vineyard, citrus and olive groves.

Militarily, Sicily is an island of strong natural defenses. Its mountains and seaside cliffs in the north command the sea approaches. The southern coast is shelving, but the terrain that lies between it and the strategic centers northward and eastward is cut by many valleys, which afford the principal lines of communication. These present a tough footing for an invader. All these natural defenses have been capitalized by the Axis. Large coastal guns and airfields have been installed in profusion. Mines have been strewn thickly in the coastal waters and planted in belts all along the beaches. Barbed wire and machine-gun nests bristle everywhere facing the sea. Naval installations, including submarine facilities, ring the island. The volcanic rock has been funneled for underground hangars and garrisons. Troops estimated at 300,000-400,000 are believed to be stationed there, and yesterday reinforcements were being rushed from the mainland across the two-mile-wide Strait of Messina.

The enemy’s power

Thus, the Allies faced formidable resistance. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Allied Commander-in-Chief, told correspondents that “we may be riding for a bloody nose,” but he thought the job could be done. Early reports from Berlin and Rome said the fighting was proving “extraordinarily costly for the invaders.” But it was obvious the Allies had not moved without vast preparation – the assembling of great strength and the most intensive training possible. The presence of the Canadians was apparently a complete surprise to the enemy. They had been in England for more than two years and in all that time they had been rehearsing landings on the beaches of the south and the rocky coasts of the north.

By these signs the importance the Allies attached to the Sicilian assault could be gauged. It was a big stake for both sides. Sicily is the doorstep of Southern Europe. It leads directly to the mainland of Italy, and the Italian peninsula leads toward the German heartland. The Alps are a barrier, but the need not be traversed. The conquest of Italy would give the Allies an all-important foothold on the continent, a powerful base for sea and air operations. Moreover, Italy flanks the Balkans, where most observers expect an Allied move at any moment and sections of which Germany has put under a state of siege.

The effects in Russia

A further significance of highest importance, lies in the effect of the Sicilian move on the Russian Front last week’s blow, like the Allied invasion of North Africa, came at a time of heavy fighting between the Red Army and the Wehrmacht. This time the Germans had just launched their long-expected 1943 offensive. They had thrown great weight into the drive but were being vigorously resisted. The sudden attack in the South came at a time when Hitler’s forces – Luftwaffe, infantry and armored divisions – were heavily committed in the East. What the result will be only the coming days will tell but it was certain that Hitler was at last faced with a second front. Before and in the early days of the war he had talked so much about the dangers of fighting on two fronts at once that it seemed an obsession. If so, Nemesis had not caught up with him. He has millions of troops, including a recent new mobilization, but there seemed to be no way in which he could possibly stretch his most needed resource – airpower – to meet the enormous demands being placed upon it. Much of it was anchored in Russia. There is believed to be a large concentration – larger than recent Axis activity would indicate – in the Mediterranean theater. And yet there was the crucial need of ever-greater air defenses against the bombing from the west.

All in all, July of 1943 had brought to the test the Hitlerian plan of world domination. No one in Allied circled expected an easy and early decision. The move against Sicily simply inaugurated the whole gigantic task of the reconquest of Europe. It seemed clear that other moves, in other sectors, were in prospect. But the attack demonstrated, in the words of a London newspaper yesterday:

Our invasion brings the war of coalition to a new point… a point at which all the United Nations are engaging every enemy and all Allied resources are converging ion Hitler’s fortress,

In Britain and the United States, military leaders were grimly cautionary, warning that heavy losses must be counted on. In the White House, President Roosevelt, confiding the dramatic news to a distinguished gathering at a dinner part for Gen. Henri-Honoré Giraud, said:

Last autumn, the Prime Minister called it “the end of the beginning.” I think you can almost say that this action tonight is the beginning of the end.