Chapter 1

Fight Like Hell‘

This is the greatest setback for German arms since 1918. The Americans will take Rommel in the rear, and we shall be expelled from Africa.’

General von Wulish, head of the German Armistice Commission, to General Auguste Nogùes, Resident-General of French Morocco at Rabat, shortly after sunrise on 8 November 1942.

The American colonel’s last-minute instructions had been brief and to the point: I want you men to hit that dock hard,’ he said, ‘then light out like stripy-arsed baboons up the wharf until you can get some cover. Then fight like hell.’

Among the detachment of the 135th Regimental Combat Team (RCT) landing from HMS Broke at Algiers harbour in the early hours of 8 November 1942, was Pfc Harold Cullum. Brought all the way from Pennsylvania and among the first to get ashore, his baptism of fire was violently cut short by two bullets, the first of which blasted a hole in his stomach and the second in his arm. Sprinkling sulphanilamide powder onto the gaping wound where chunks of clothing and equipment had been driven deep into the flesh, he wrapped his shattered arm in a field dressing and, when the recall whistle blew, attempted to crawl back to his ship. Eventually taken prisoner, he ended up in a French hospital where expert attention saved his life.

Yet it was French gunfire which had wounded him in the first place. The British and Americans, in the massive gamble that they had code-named Operation Torch, had brought more than 107,000 men across the oceans to the shores of North Africa in two mighty armadas, and in three simultaneous landings placed them ashore at Algiers, Oran and Casablanca.

At Casablanca and Oran, the French resisted this invasion of their colonial territory: ill-fated attacks on Algiers and Oran harbours were bloodily repulsed; and parachute drops by Colonel William C. Bentley’s 2nd Battalion, 503rd US Parachute Infantry Regiment, to secure airfields at Tafaraoui and La Senia, south of Oran, turned into near-disaster. Nevertheless, the scale and speed of the Allied invasion ensured the narrow success of their great venture, though much remained to be done to bring together warring French factions. One was led by General Henri Giraud, who had escaped from German prison camps in two world wars, and claimed imperiously that he could rally all the French in North Africa to the Allied side – the other by Amiral de la Flotte Jean François Darlan.

Operation Torch came into being principally because the two most powerful men in the Alliance, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Britain’s Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, wanted it. Churchill had clear, long-term, objectives which he put forward with his customary vigour. An assault in North Africa would remove the Germans and Italians from the region, help to secure critical British supply lines through the Mediterranean and build a base from which Allied troops could springboard their way into southern Europe. Roosevelt, who had promised Stalin that a ‘Second Front’ against Nazi Germany would be opened in 1942, had been caught on the point of this guarantee. Unwilling to abandon the British in their hour of need, for once during the war the President overrode the advice of his own Joint Chiefs of Staff, settling for an assault in the Mediterranean which Churchill and the British Chiefs of Staff Committee had called for time and again.

In the Mediterranean, Germany was locked in a struggle not of her own making. Against the unanimous opposition of his generals, Benito Mussolini committed his forces to a desert war in September 1940, despite the unpreparedness of the army, which had few motorised vehicles, modern artillery or tanks, and a limited industrial power-base incapable of remedying these deficiencies or provisioning his troops. The arrival of German forces in North Africa in the spring of 1941 was conclusive proof of the failure of Mussolini’s hopes of a cheap triumph. They arrived not to pursue a particular military objective, nor as part of a broad strategic plan, but simply to support the Italians, check the British advance to Tripoli and possibly regain Cyrenaica.

The German forces in Africa were placed under control of Comando Supremo (Italian Supreme Command) while Hitler’s headquarters, the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW or High Command of the Armed Forces), initially limited itself to advice and supplies. As German involvement increased, however, Feldmarschall der Luftwaffe Albrecht Kesselring left von Bock’s Army Group Centre on the Eastern Front and flew to Rome in November 1941 where he was appointed Oberbefehlshaber Süd (OB Süd or C-in-C South).

Kesselring was ideally suited to his task. Known as ‘Smiling Albert’ from his habitual grin and highly optimistic temperament, he had been Chief of Staff of the Luftwaffe in 1936–37. In creating a close working relationship with the heads of the Italian armed forces he came across an old friend, General Rinso Corso Fougier, of Superareo (Italian Air Force High Command), who, according to Mussolini’s son-in-law and foreign minister, Count Galeazzo Ciano, was ‘a real pilot, not a balloon officer.’ The other Italian armed forces’ chiefs were Marshal Ugo Cavallero, Chief of the General Staff, and Admiral Arturo Riccardi of the Supermarina (Naval High Command). A man of immense organizational and administrative abilities, Cavallero was undoubtedly pro-German; indeed, he co-operated to such an extent that his own position became endangered. He was replaced by General Vittorio Ambrosio in February 1943, which ‘produced joy among Italians and dissatisfaction among the Germans.’

In the struggle for North Africa only the Luftwaffe was clearly and unequivocally under OB Süd control. Other than this, there were overlapping German-Italian commands which resulted in Kesselring taking orders from the OKW in some matters and from Comando Supremo in others. Only his strong personality held the ramshackle organization together and resolved some of the tensions arising from these confused relationships. His HQ moved from Taormina in Sicily to Frascati near Rome in October 1942, so that by his presence Kesselring could exert a stronger influence on Comando Supremo over German supply problems.

Kesselring’s ambiguous command relationships were compounded by the lack of consistent leadership from inside OKW, as Hitler increasingly overrode his General Staff’s advice and insisted on more and more ‘Führer decisions’ in the face of setbacks in Russia and elsewhere. The invasion of North Africa therefore hit the German High Command at a critical moment.

The first danger was averted by General Walter Warlimont, Deputy Chief of the OKW Operations Staff, and Kesselring, whose frantic staff work ensured that Hitler’s initial response to the landings was speedily translated into the formation of a bridgehead in Tunis and occupation of Vichy France. At 0700 hours on 11 November 1942, ten divisions of the German First Army and Army Group Felber crossed the demarcation line between German-occupied northern France and the unoccupied territory to the south which had been governed until then by the puppet Vichy regime. At the same time, two Italian divisions from Sardinia landed on Corsica and units of the Italian Fourth Army marched into the French Riviera. To the surprise of Hitler’s HQ, there was virtually no resistance.

In Algiers the French were shocked by the pitiless way in which the Führer discarded the armistice of 1940. Even so, they could not reconcile their differences. Admiral Darlan ordered the French commanders in Tunisia to resist the Germans, countermanded his order and then reinstated it. At Allied Force Headquarters (AFHQ), Gibraltar, the Commander-in-Chief, Lieutenant-General Dwight D. Eisenhower, raged over the venomous squabbling and was in such a fury ‘that I sometimes wish I could do a little throat-cutting myself.’

Eisenhower’s appointment as C-in-C had been a surprising one. He had graduated from West Point in 1915, without particular distinction, and was posted to the 19th US Infantry Regiment at Fort Sam Houston on the outskirts of San Antonio. Despite strenuous efforts, he failed to be listed for overseas duty when America entered the Great War in 1917 and remained labelled as no more than a useful trainer of troops and desk officer: ‘I had missed the boat,’ he later remarked.

During the inter-war period he served under various powerful leaders in an effort to avoid a career dead-end, imbibing much of the politics and bureaucratic niceties characterising the higher forms of military life. Only later, under the tutelage of Roosevelt’s US Army Chief of Staff, General George C. Marshall, did his career really blossom. Marshall brought Eisenhower to the War Department in December 1941, and thereafter there remained a close personal link between the two. Eisenhower was always the junior in rank, but became the best-known US military leader of the war, satisfying the public’s craving for an all-American war hero. In the autumn of 1942, however, the new C-in-C was virtually unknown outside military circles. He had no combat experience and was viewed with baffled scepticism by the British who could not understand how a man could be produced from comparative obscurity to hold the highest command.

Eisenhower proved to be dutiful to a marked degree, with great application to the task in hand, a keen eye for detail and a ruthless streak which implied superlative determination. He could also be impatient and brutally abrupt with those whom he discarded. His public character, however, was entirely different. It was that of a friendly and relaxed small-town American, his speech peppered with homespun phrases reflecting his roots deep in his native Abilene soil. Eisenhower was adept moreover at promoting this image to the British and American publicity machines which were more than happy to play along. He was in addition a peerless chairman of inter-Allied committees, arbitrating smoothly between rival plans. No visionary, nevertheless he saw clearly that it was vital for American and British staffs, and the troops they ultimately commanded, to work together at all levels.

Eisenhower’s deputy, Major-General Mark W. Clark, had to bear the brunt of French wrangling at Algiers. Long-limbed, beak-nosed and intensely, disagreeably ambitious, he eventually lost his temper and threatened the squabbling leaders with immediate custody and the establishment of military government. This settled matters and when Eisenhower arrived he had only to endorse the agreement which had been reached. Having now definitely joined the Allied side, Admiral Darlan was to head the civil and political government of North Africa, Giraud to be C-in-C of all French forces and General Alphonse Juin to command a reinforced French volunteer army fighting alongside the Allies; Noguès (French Morocco) and Chatel (Algeria) would retain their Resident-General posts.

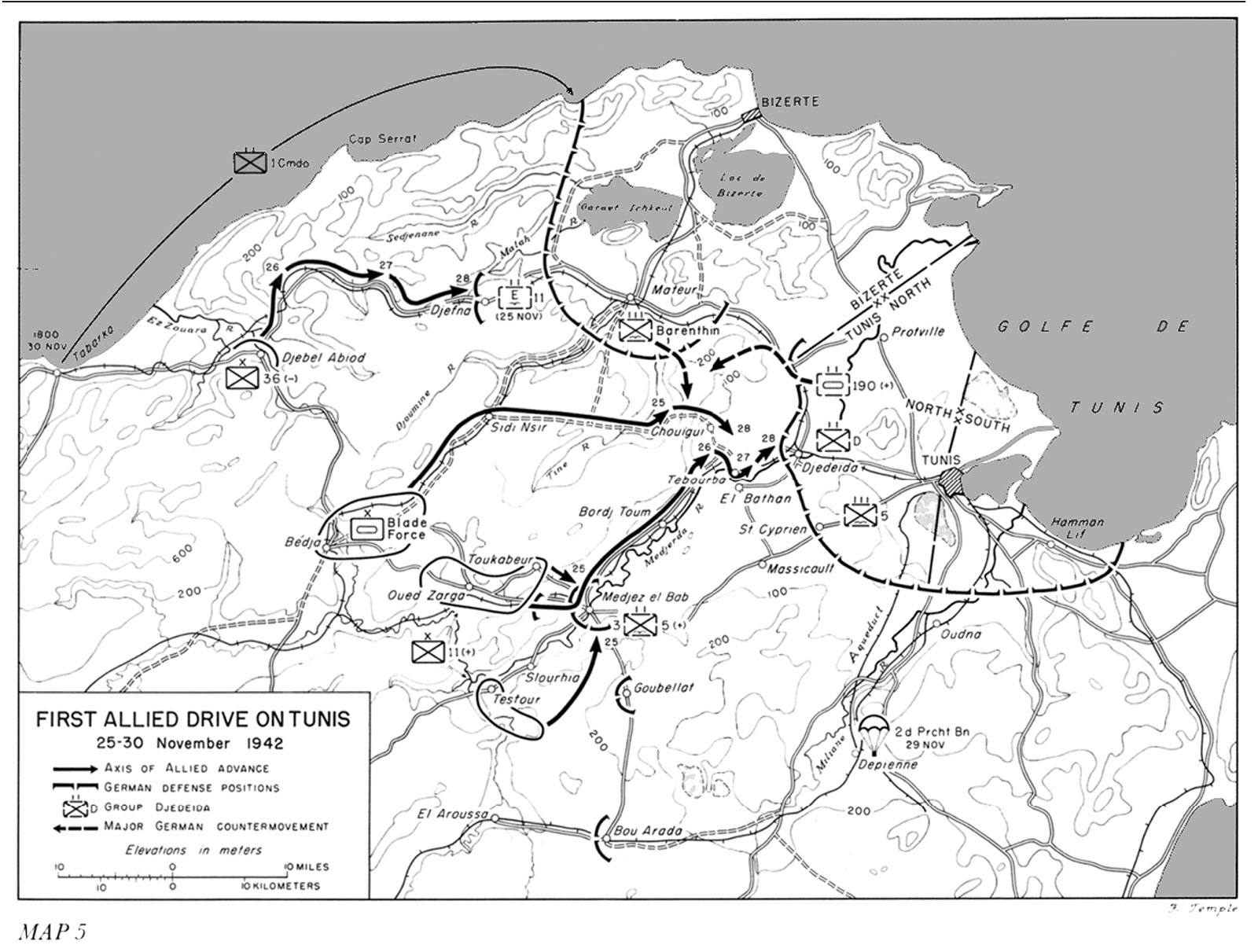

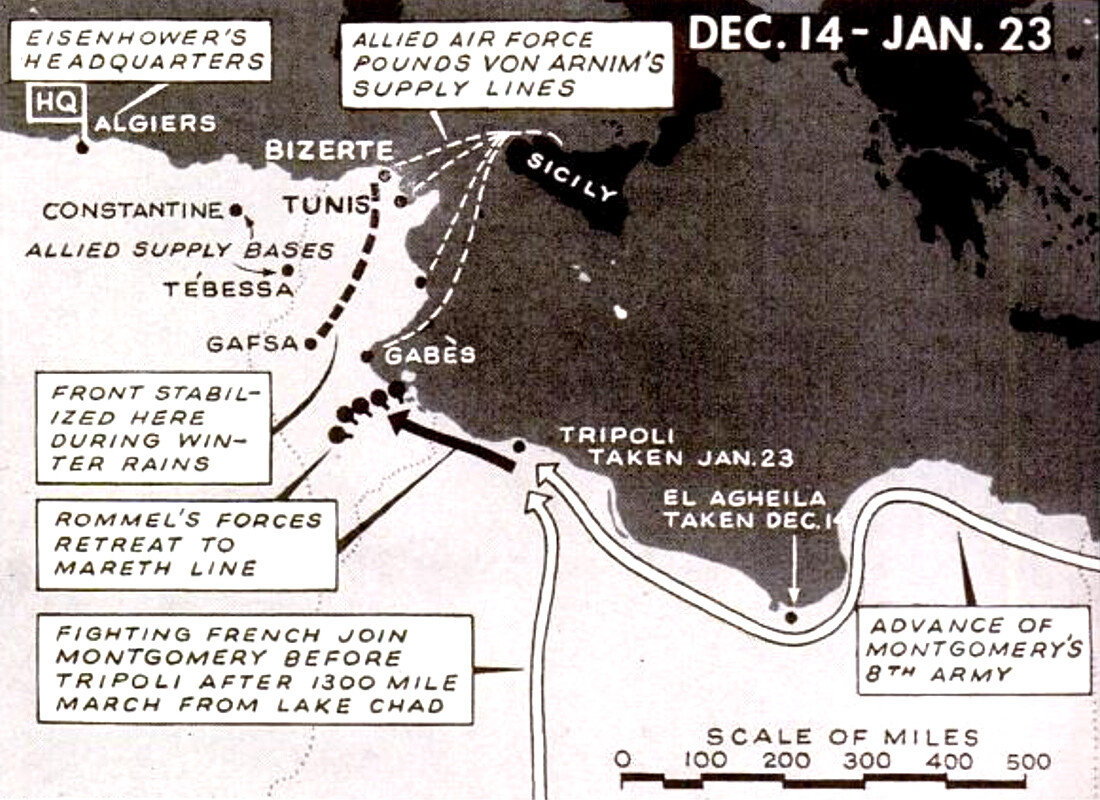

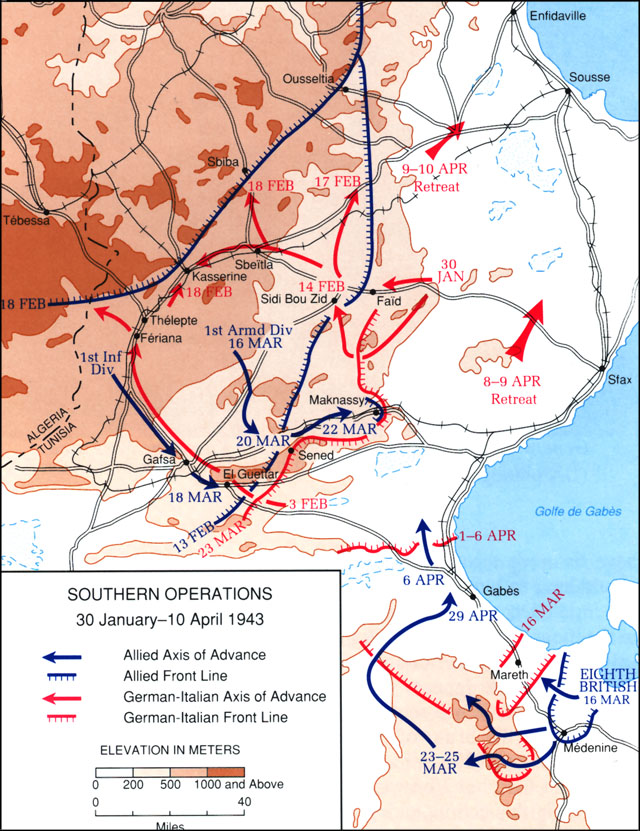

Meanwhile, at OB Süd HQ it was not yet clear whether the German High Command planned to hold Tunisia at all costs or simply carry out a limited engagement in order to defend Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel’s lines of communication in the Western Desert and prevent a disastrous collapse of Italian morale. The Allies for their part intended to squeeze Rommel’s forces in a trap between Eighth Army, now advancing from Egypt through Tripolitania, and First Army operating from Tunisia.

From the outset, however, Allied planning had been characterised by indecision; the Americans, anxious about possible hostile reactions from the Spanish dictator, General Francisco Franco, worried about opposition from Vichy France and fearful of a German move against Gibraltar which might close the Strait and cause havoc for the Allies, proposed to consolidate their positions in French Morocco for about three months before advancing eastwards.

British planners went for a bolder design. They had insisted on a deep strike into the Mediterranean itself, at Algiers, and, in conjunction with the Eighth Army sweeping in from the west, a swift move on Tunis before the enemy could effect a bridgehead there. Indeed, Lieutenant-General Kenneth Anderson, given the task of pushing eastwards once the Allies landed in North Africa, wanted an early attack on Tunis and even suggested that US aircraft land there on the morning of the Torch assault – though even if the bluff worked the crews would, in all probability, be taken prisoner. As the British correctly predicted, once firmly established, with their shorter lines of communication and land-based air power, the Axis forces would be difficult to prise out.

Early on the morning of 9 November 1942, two German officers, Hauptmann Schürmeyer and Hauptmann Behlau, arrived in Tunis. Under the pretext of helping the French resist the Allied invasion they discussed defence of the city with the Resident-General in Tunisia, Vice-Admiral Jean-Pierre Estèva – ‘an old gentleman with a white goatee’ – the Commandant Supérieur des Troupes de Tunisie, General Georges Barré, and the local French air force commander, General Péquin. They had been ordered by the head of the Vichy Government, Pierre Laval, to co-operate with the Germans.

While these discussions were taking place, Kesselring ordered one of Göring’s intimate friends and a former fighter pilot in the First World War, Generaloberst Bruno Loezer, commanding Fliegerkorps II from Taormina in Sicily, to fly fighters and Stukas across and seize the airfield at El Aouina (Tunis). Accordingly he sent elements of the 53rd Fighter Squadron and transport aircraft, carrying supplies of fuel, oil and light flak guns. Colonel Geradot, the commander of the airfield, narrowly escaped and hastened by air to the British First Army’s command post, established that day at the Hotel Albert in Algiers. He brought discomfiting news that 40 German bombers already sat on the tarmac at Tunis.

The fiction that these forces were being invited to aid the French was maintained by sending Oberstleutnant Harlinghausen of Fliegerkorps II to Tunis to see Estèva. Believing the French offered no opposition, he alerted OB Süd and, next day, a fighter group of Me-109s and Kesselring’s Wachkompanie (personal HQ Company) carried in gliders towed behind Ju-88 bombers, were on their way from Sicily. As each aircraft taxied to a halt at Tunis, it was covered by the guns of a French armoured reconnaissance car. For a while, matters were in the balance until transport planes brought in the 5th Fallschirmjäger (Parachute) Regiment. Scrambling out, a company set up its anti-tank weapons and machine-guns and trained them on the armoured cars. The French withdrew to the outer perimeter and an uneasy peace settled over the airfield.During this time, Loezer was again telephoned by Kesselring who told him that Barré and Estèva were communicating with the Allies via a cable linking Tunis to Malta and by a secret radio operating on the roof of the US Consulate. Loezer was told to see that no further messages were transmitted. Arriving at Tunis, Loezer found the troops who had just flown in still organizing themselves. The resident German Armistice Commissioner warned Loezer that the situation was exceedingly delicate and it was with ‘mixed feelings’ that Loezer passed through French troops on his way into the city. ‘The men made a good soldierly impression,’ he wrote. ‘I saw no officers. Machine guns and anti-tank weapons were trained on the airfield.’ He was met by Barré’s representative, frostily polite, who could give no assurances about French co-operation. Estèva was more encouraging, assuring Loezer he had received instructions from Vichy and would do everything to help, on the understanding that the Germans were to be restricted to airfields at Tunis and Bizerte (Bizerta). French forces had orders to shoot if they strayed elsewhere.

Loezer, satisfied with what he had seen and heard, made his way back to the airfield. Not a man moved to detain him though this would have been simple enough, as he observed: ‘There can be little doubt that the small air forces with their planes on the ground would have been easy prey for the French troops in readiness there if they had attacked in this situation.’

The same was true at Bizerte airfield, occupied on 11 November, without a shot being fired, by a single Ju-88 and two sections of the Ahrendt parachute engineering column. Again the French stood off and allowed the Germans to reinforce their bridgehead.

‘The French behaviour is inexplicable,’ complained Brigadier Haydon vice chief of the Combined Operations staff at Gibraltar, ‘The Germans, Italians and Japs appear welcome in any French possession ! We who were their Allies and who are fighting for their ends as well as our own, are resisted at every turn. It is high time they were called upon to declare themselves one way or another.’ But the chronic indecision which beset the French leaders ensured this would not happen. ‘I thought there would be some gesture of opposition, at least for the honour of the flag,’ commented a surprised Ciano. Its absence provided a window of opportunity for the Germans in Tunisia, which they were quick to exploit, in turn condemning the Allies to a costly and extended campaign.