Chapter 15

Go On At All Costs

‘Where are you Eighth Army people going?’

‘Tunis.’

‘Where then?’

‘Berlin.’

Exchange between Brigadier Kippenberger and a captured German officer at the Wadi Akarit, April 1943.

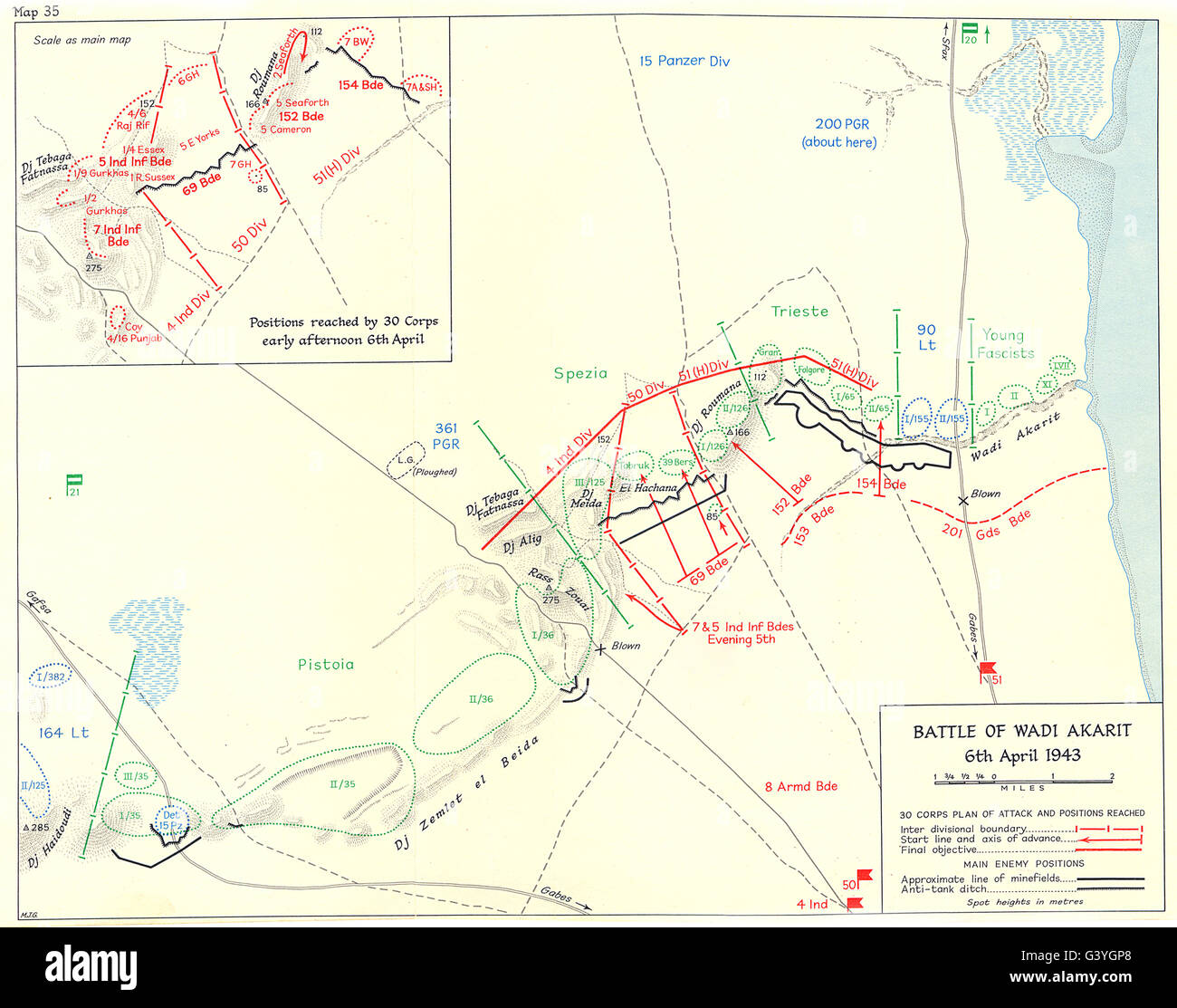

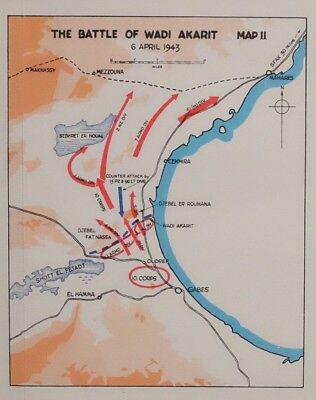

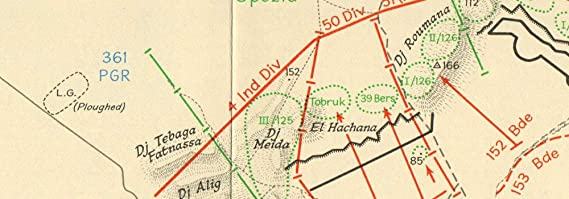

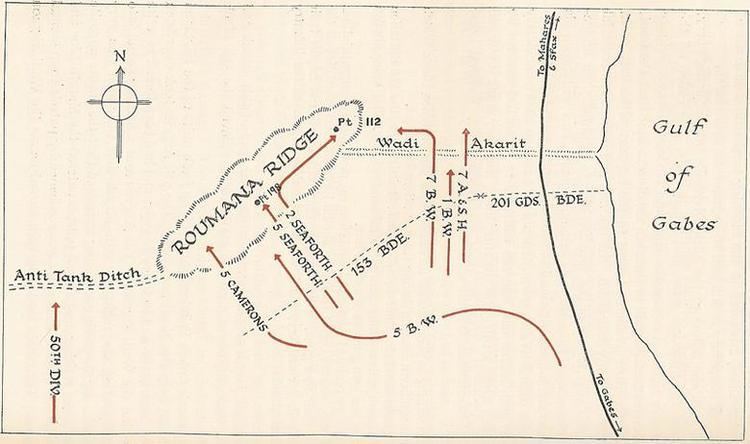

Advancing through the Wadi Akarit position on 7 April, Sergeant Caffell saw for himself the grim cost of its capture: ‘Some of our own dead infantry boys still lying unburied face down on the battlefield. I had to keep wrenching the steering wheel to avoid driving over them.’ Eighth Army’s casualties had been higher than at any time since El Alamein. In 24 hours 1,289 men had been killed or wounded, 51st Highland Division suffering most heavily. Among them was Brigadier Kisch, Eighth Army’s chief engineer, blown up when someone stepped on a mine. ‘He had an eye like a hawk for mines and was our great anti-mine expert,’ observed Leese, ‘and would never have made a mistake. He is a terrible loss.’

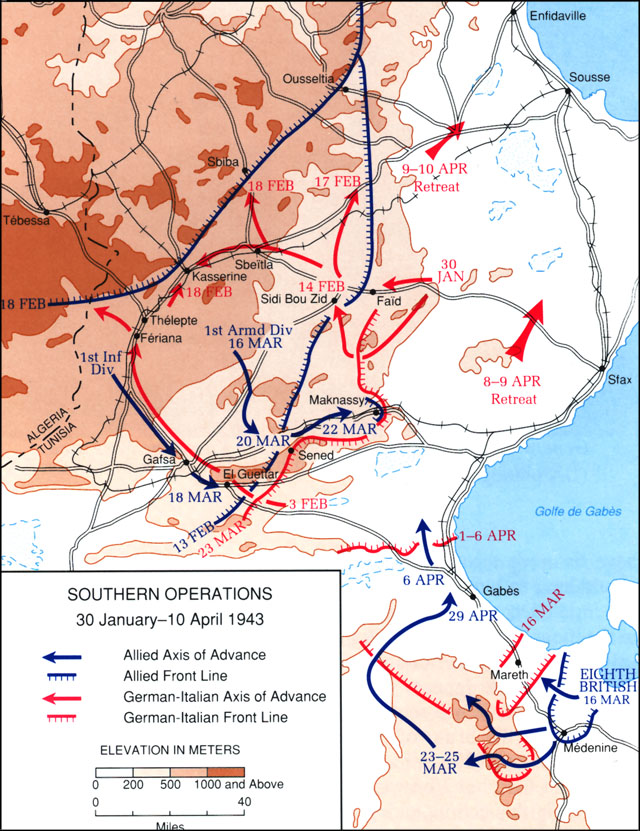

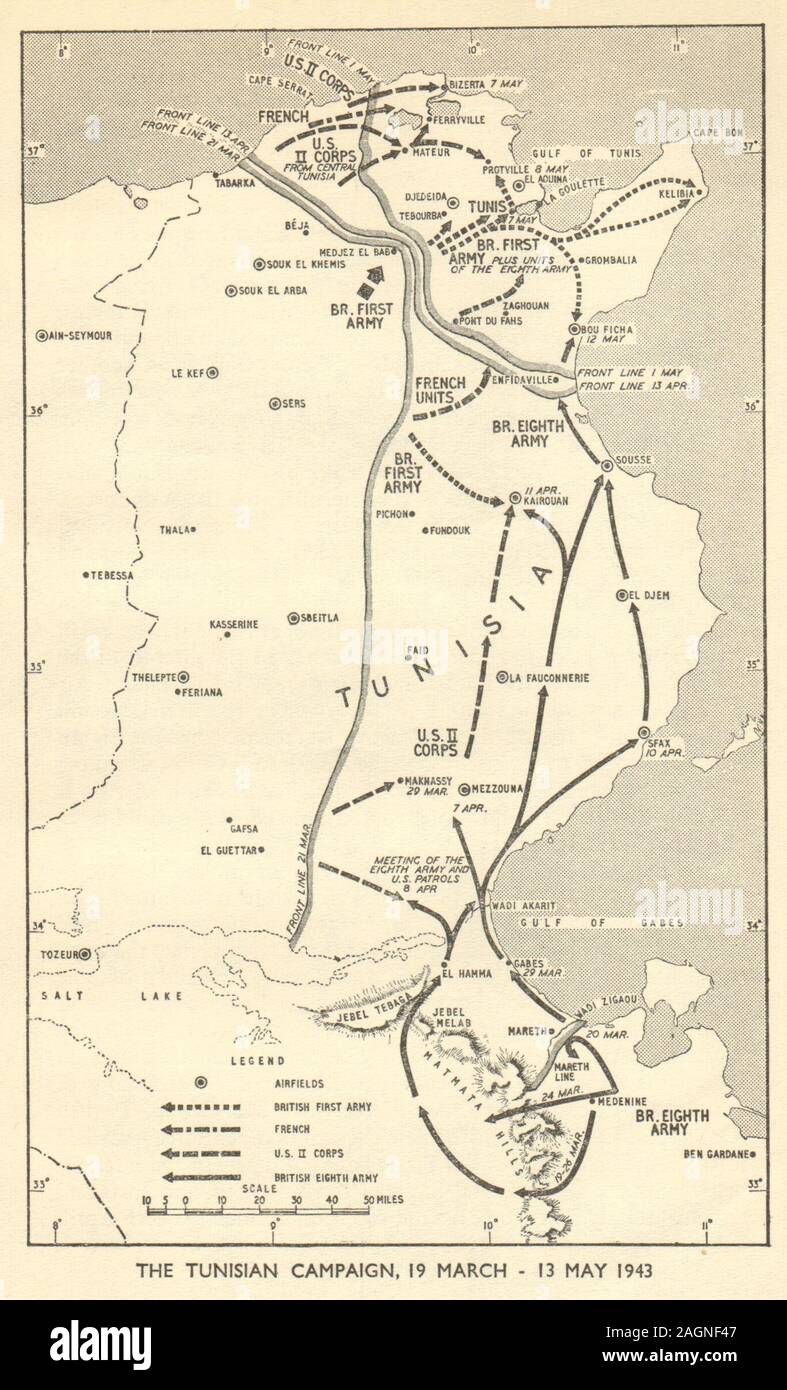

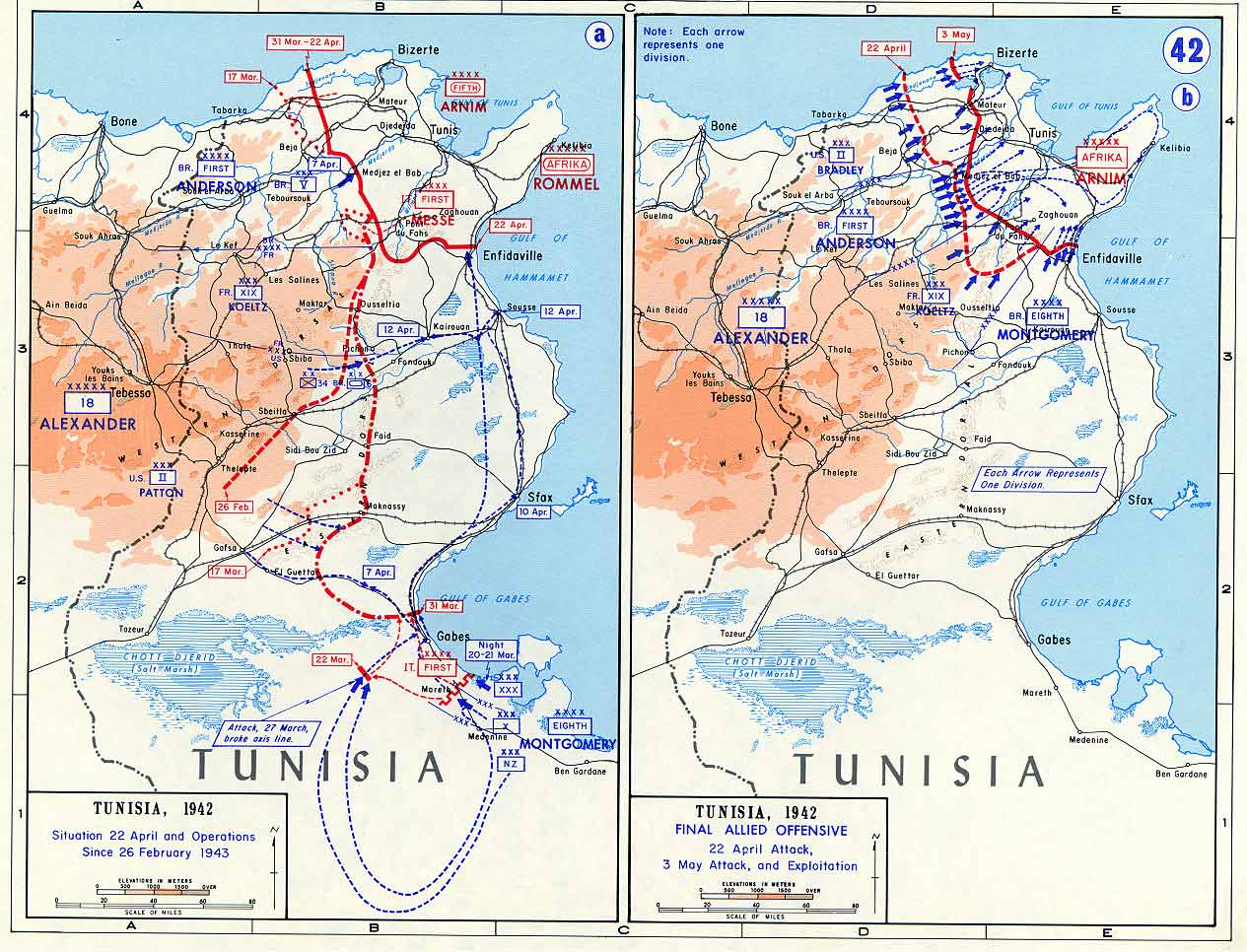

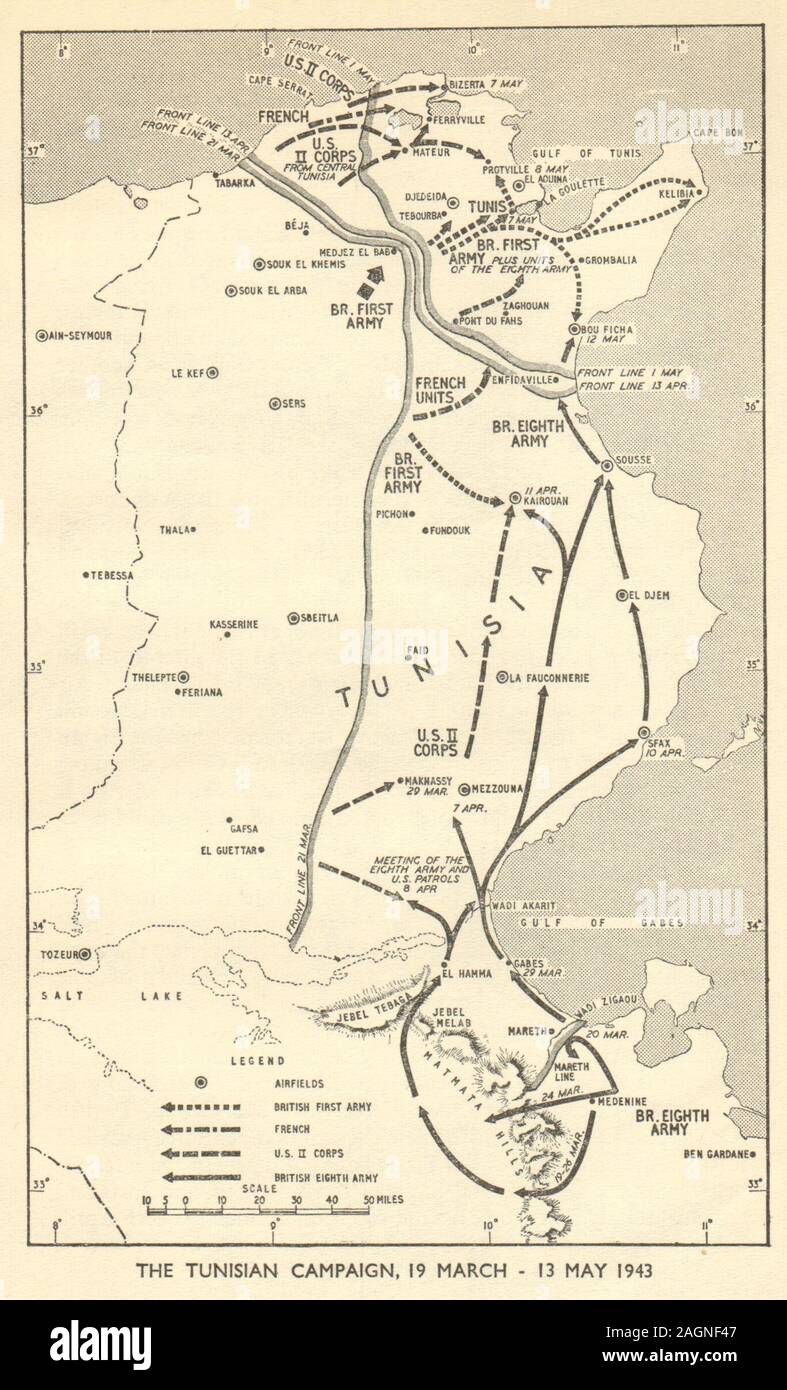

Still , Montgomery was triumphant. First Italian Army had lost further 7.600 men in Wadi Akarit and thrown away from its defenses. RAF air reconnaissance and Y Intelligence reported early on 7 April that, ‘all elements’ were withdrawing from the Wadi Akarit, as well as 10th and 21st Panzer Divisions from in front of Patton in the El Guettar-Maknassa area. ‘Violent enemy gunfire and bombing. The enemy is attacking and is beaten back,’ recorded the Gefreiter for the last time (4–6 April) in the diary he had kept during the long retreat. Whether he was killed or was among the 125 Germans taken prisoner – together with 5,211 Italians – is not known. In all, First Italian Army had lost about six battalions.

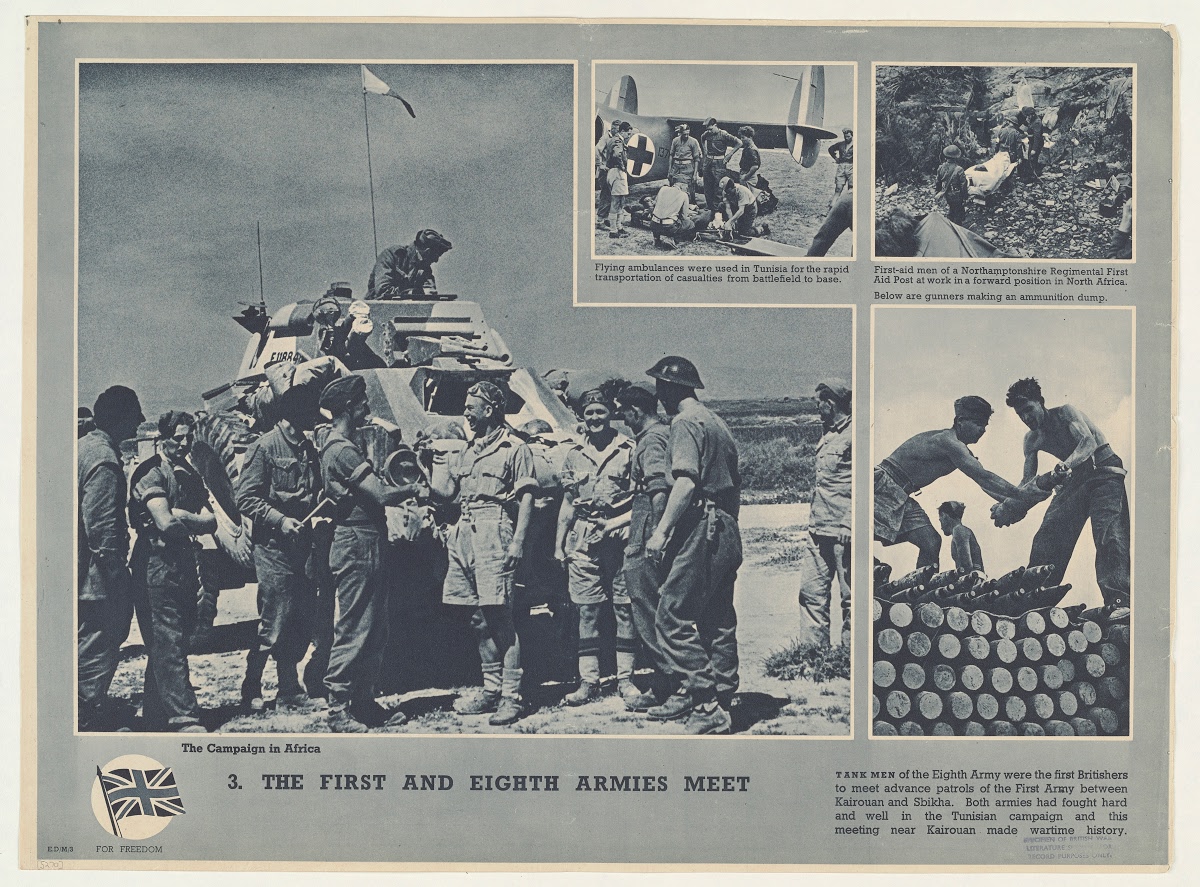

That same morning Patton sent Benson’s armoured column ahead from El Guettar, meeting with little resistance except some long-range fire. At about lunchtime, Patton moved up to join Benson and came upon his tanks held up in front of a minefield; ignoring the mortal danger he drove on while they followed and then told Benson, ‘keep pushing for a fight or a bath [in the sea].’ Turning back when only 40 miles from Gabès, Patton came across, ‘quite a few prisoners, including Germans of a low type.’ Shortly after, a British patrol met what Tuker termed, ‘the Yanks… right hand tank’. Lieutenant Richardson’s No. 5 Troop, B Squadron, 12th Lancers, came across Benson’s armour south-west of Sebkret en Noual at 1530 hours and the junction between Eighth Army and 2nd US Corps had at last been accomplished. ‘I am glad I was not there,’ noted Patton, ‘It would have been too spectacular.’

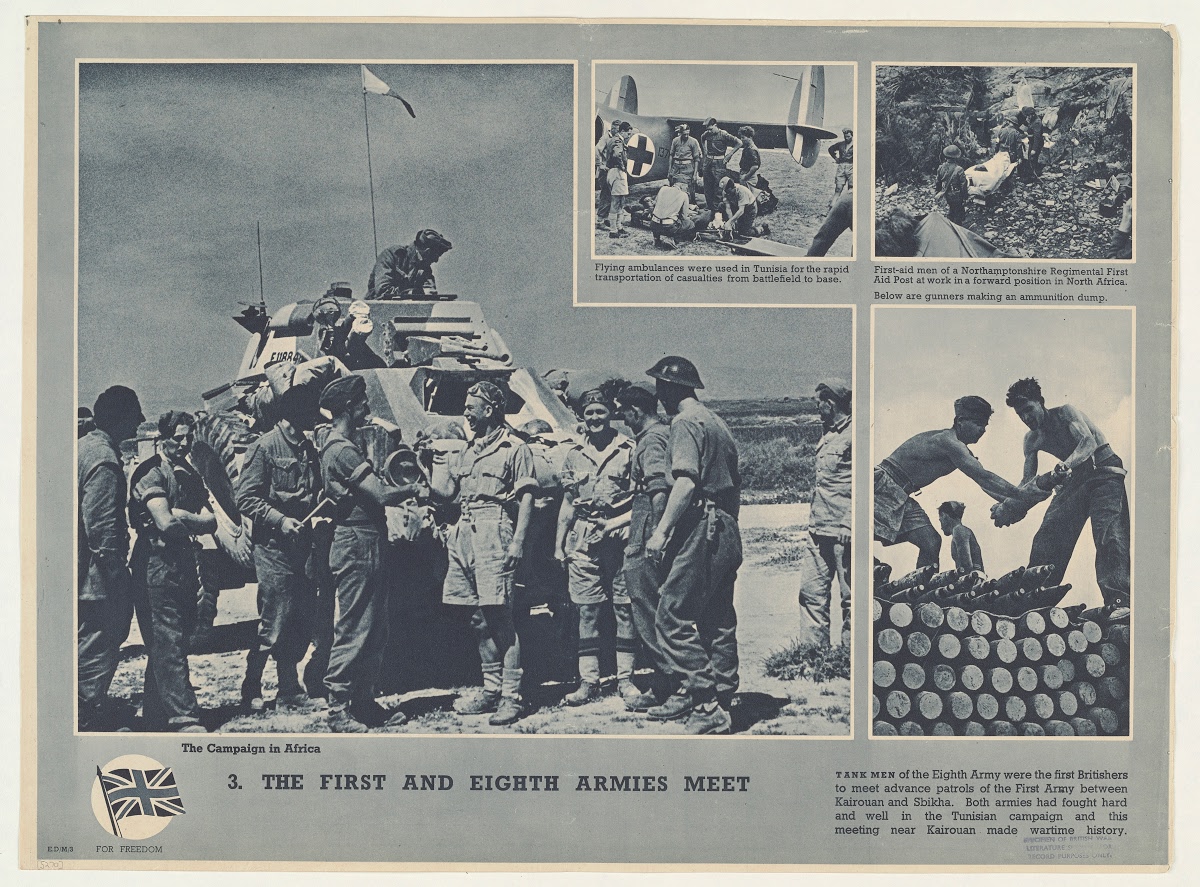

The encounter was anything but that. ‘Say, where’s the booty?,’ was the first question asked by the Americans. Brisk and unemotional, representatives of two armies which had started out from opposite sides of a continent shook hands for the movie cameras. ‘Seems to be end of [one] phase & start of another,’ commented Hansen. The meeting effectively ended the battles around El Guettar and Gafsa; much to Patton’s annoyance he was ordered that evening by 18th Army Group to recall Benson’s armour.

Alexander’s intention now was to cut off the retreating Axis troops further north by striking eastwards with Crocker’s 9th British Corps through the Fondouk Pass, between Djebels Haouareb and Rhorab. In the south the hunt was on as Eighth Army began to move forward over the network of roads dividing the great central Tunisian plain. Nearest the coast, 51st Highland Division was held up by the antitank ditch east of Roumana where Major Rainier saw a bulldozer burying heaps of enemy dead. On the Highlander’s left, 7th Armoured raced ahead accompanied by the New Zealanders, with 8th Armoured Brigade under command spreading westward and linking with 1st British Armoured furthest inland.

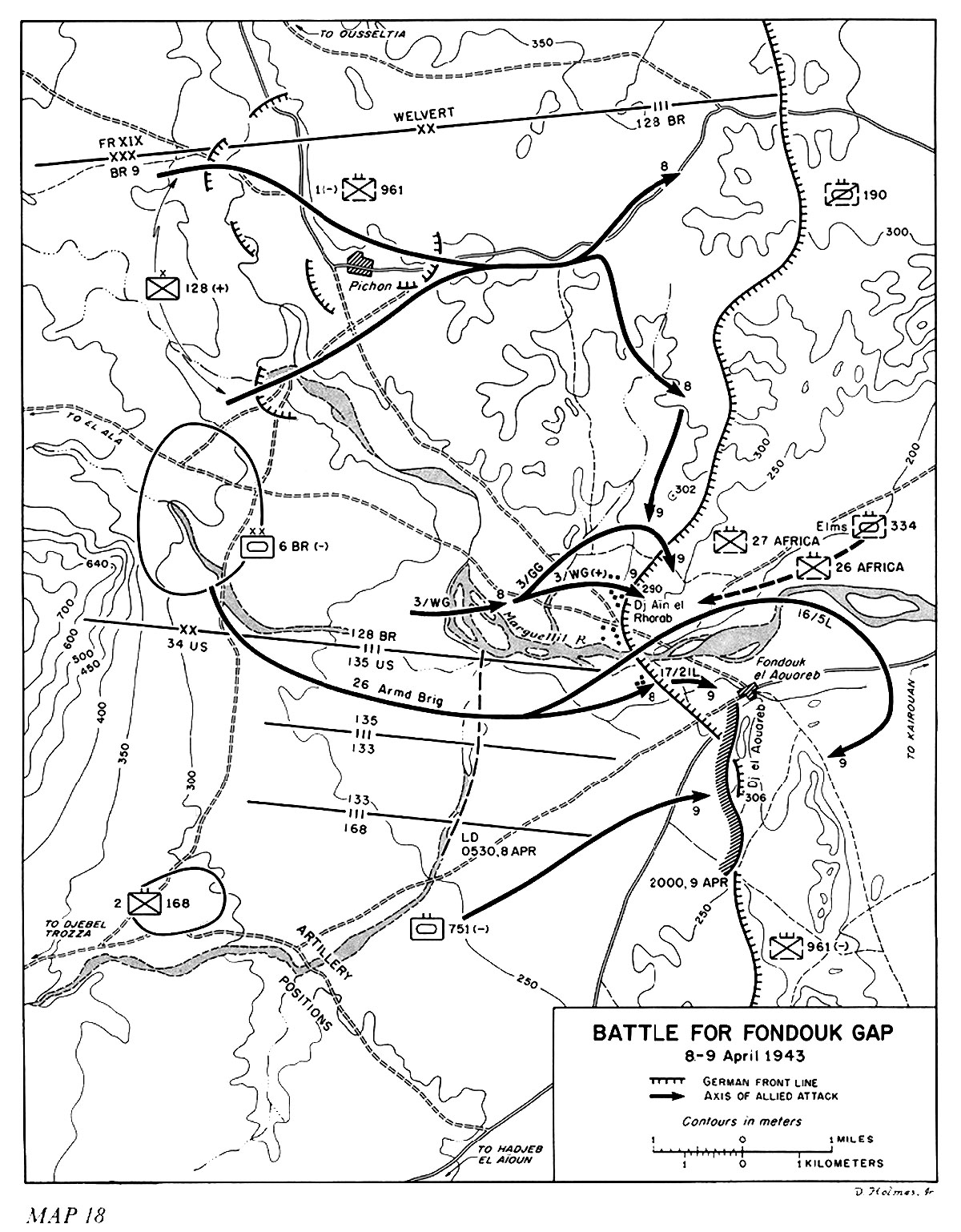

Delaying actions were fought by 361st Panzer Grenadier Regiment, and tanks moving north-east from Gafsa and El Guettar, though they were heavily strafed by the Desert Air Force. Meanwhile, Bostons, Mitchell bombers and Kittyhawk fighter bombers cratered the Luftwaffe’s landing grounds. Fritz Bayerlein reported heavy casualties and unsettled morale. But, to general dismay, Eighth Army soon discovered that the great bulk of the enemy forces had carried out a remarkable retreat to new positions and that its own logistical difficulties prevented a rapid advance.The last remnants of First Italian Army quickened their retreat on 8 April as Crocker ordered Brigadier James’ 128th Infantry Brigade, whose Churchill tanks had arrived in a great hurry only 36 hours earlier, to attack across the Wadi Marguellil, which winds through the Fondouk Pass and stretches to the south-west of Pichon. Taking the village they advanced further eastwards to smash the enemy’s Algeria Battalion and then, lacking any clear orders, they turned south towards Djebel Rhorab, four miles away, with a force consisting of 5th Hampshires and a squadron of tanks from 51st Battalion, RTR. They were stopped by increasing resistance from 1st Battalion, 961st Regiment.

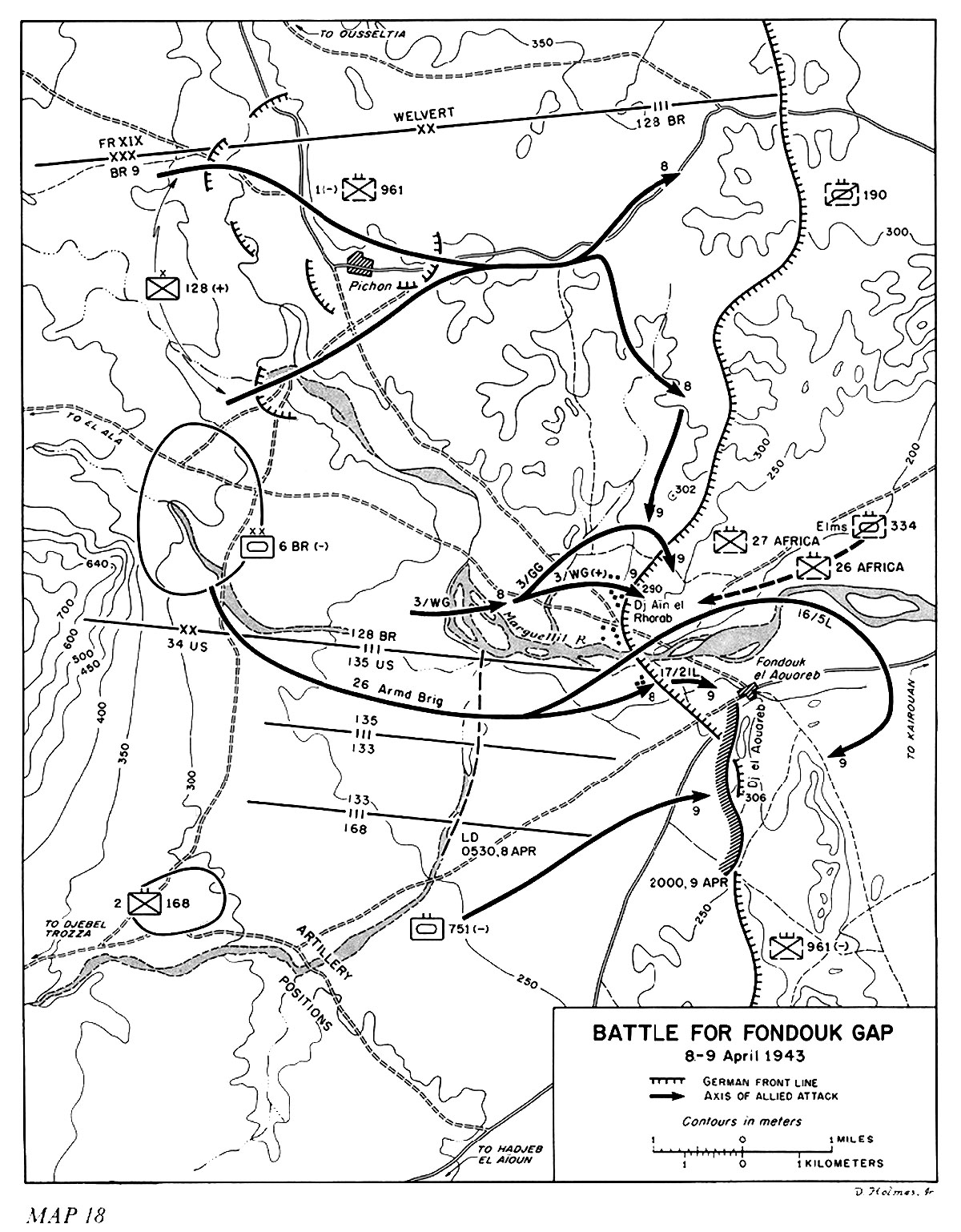

Crocker’s basic plan of attack at Fondouk was inept because Djebel Rhorab, threatening his right flank, was not included as a definite objective for 128th Brigade. Brigadier James had been told to deny its use to the enemy – not quite the same thing as capturing it. Meanwhile, 133rd and 135th Infantry Regiments (Ryder’s 34th US Infantry Division, not yet fully trained), supported by Shermans of the 751st Tank Battalion and two companies of the 831st Tank Destroyer Battalion, were to capture the heights south of Fondouk between Djebels Haouareb and el Jedira. ‘Once more our infantry doggies went up against that damned saw-toothed ridge,’ commented one officer.

Understandably anxious that Rliorab would not be taken by the time his troops left their start line, Ryder managed to get Crocker’s agreement for his attack to go in at first light, after bombing and shelling had softened up the Germans. Crucially, he then changed his mind. Still overwhelmingly concerned about the danger on his right he ordered a night approach when the troops were already past the 2,000 yard bombline. Corps HQ cancelled the bombing for fear of hitting 135th Regiment as it advanced and, while the inexperienced troops milled about trying to find their bearings, the American artillery opened up on Djebel Haouareb. Far too soon, their shelling simply awakened the Germans and gave no cover to the infantry who had barely started to move forward.

After further delay and asked to advance four miles over open ground in broad daylight against withering fire from the 961st’s 2nd Battalion on their front and left flank, the attack units refused to leave their start line, dug shallow trenches, hid in the beds of dry wadis or lay full length behind sand hummocks. While their courage was not in doubt they lacked experience and leadership in such a daunting situation. Many had served mainly on line of communication duties and, when others had previously been committed to battle, their losses had been made up by replacements who, ‘generally seemed to be below average in physical fitness, training and mentality. Quite a number of them had never had the benefit of a field manoeuvre and were not accustomed to overhead artillery fire which further decreased their efficiency temporarily. An excessive number of over-age and physically unfit men who could not stand the rigours of battle were received as replacements.’ These were men sent to assault units within 48 hours of arriving at the front.Crocker was under great pressure to cut off First Italian Army as it streamed north but badly underestimated its strength at the Fondouk Pass. Intelligence sources had rightly located part of 999th German Division and Marsch Bataillon 27, though estimates of their fighting potential – particularly of the ex-convicts – were low. As a tank expert, who fought in the battle of France and founded and trained 6th British Armoured Division, John Crocker possessed a near-obsessive drive for perfection amongst his tank crews but demonstrated little understanding of infantry. Neither could operate successfully without the other but he believed that putting Keightley’s armour through the Fondouk Pass and on 14 miles to Sidi Abdullah Mengoub – where 1st Guards Brigade would establish a solid base from which marauding tanks could cut off the retreating enemy – was relatively an easy task and one in which the infantry, on both sides, would play a minor role.

Keen to exploit as soon a possible he ordered Brigadier ‘Pip’ Roberts, switched from Eighth Army to command 26th Armoured Brigade, to send his Shermans off on a powerful reconnaissance. At about midday leading elements from 17/21st Lancers cut across the Americans at Fondouk just as they were beginning a reorganized attack, creating massive confusion and drawing more devastating fire which destroyed four tanks before the probing Lancers hastily withdrew. To their credit the shaken Americans sent in their own armour again which reached the foot of Djebel Haouareb. There, unsupported by infantry, they were easy meat for the cleverly sited German anti-tank guns and dual purpose 88s.Intensely frustrated by the previous day’s events, Alexander told Crocker on 9 April to smash through with 6th British Armoured Division and trap the Panzers hurrying towards Enfidaville, irrespective of whether or not the Americans had cleared the ridge south of Fondouk. Still unable to comprehend that the enemy held Djebel Rhorab in force, Crocker by-passed Keightley and ordered the capable and experienced Roberts to force the pass with 26th British Armoured Brigade, whatever it cost. At the same time the Welsh Guards, from 1st Guards Brigade (transferred from 78th Division to 6th Armoured on 24 March), unsupported by prior artillery bombardment or tanks would attack up the steep slopes of Rhorab.

The colossal task of grinding through the enemy’s double minefield and piercing his anti-tank screen was revealed to the squadron leaders of 17/21st Lancers at 0930 hours. ‘Goodbye – I shall never see you again, we shall all be killed,’ said young Major Nix to his tank commanders before leading the attack. Nevertheless, they advanced almost a mile over heavy sand before he radioed: ‘There’s a hell of a minefield in front. It looks about three hundred yards deep. Shall I go on?’ ‘Go on,’ he was told. ‘Go on at all costs.’

Only a few advanced with the gallant Nix beyond the village of Fondouk where he was killed by a shell which punched into his Sherman. All but two of his squadron’s tanks were disabled or destroyed and a second squadron, seeking a path through the deadly minefield, fared almost as badly, becoming bogged down and then shot to pieces.

Probing to the left of the pass, 16/5th Lancers at last discovered a safe route for the advance by running its tanks down into the bed of a wadi which was now firm enough to support their weight but had been too wet to allow the Germans to lay mines. Behind came 10th Rifle Brigade and 2nd Lothians, passing on either side derelict tanks, broken tracks hanging limply over top rollers, bogies and suspension units blown off.

The Welsh Guards had meanwhile suffered heavy casualties in their struggle to take Djebel Rhorab. After three hours all four rifle companies were pinned down and in intermittent wireless contact only; most of their senior officers and NCOs were dead or wounded. Just when everything seemed lost, the adjutant, Captain G.D. Rhys-Williams, rallied the shaken Guards and led them in a new attack at 1300 hours. As they closed in for the kill he was heard calling, ‘Keep your distance, not too fast. Come on boys, we can do it.’ Disappearing over a final crest he was discovered only minutes later, kneeling in the act of re-loading. He was quite dead, shot by a German sniper. But his outstanding heroism drove home the attack: Djebel Rhorab was finally taken and down from the peak came over 100 dishevelled German prisoners.

Battle of Fondouk gap

Having reached a point from where they could break out beyond the Eastern Dorsale, 16/5th Lancers and the Lothians lay immobile during the hours of darkness on 9/10 April. This delay was crucial in allowing further units of Messe’s army to retreat northwards; it resulted from a simple misunderstanding. Word had been received that 10th and 21st Panzer Divisions had left Eighth Army’s front and were on their way to parry 26th British Armoured Brigade’s thrust. What had actually been sighted east of Fondouk, at about 1730 hours on the 9th, was Bayerlein’s flank guard protecting the main German forces as they passed along the Kairouan plain, following the tracks of Italian elements left the previous evening. A few German tanks which approached Crocker’s force were quickly seen off and four German self-propelled guns abandoned and captured by British infantry, but he remained worried about the enemy on Djebel Haouareb who had not been completely subdued.

As Crocker hesitated his opposite number, Oberstleutnant Fritz Fullriede, was reporting to Heeresgruppe Afrika that his right flank (where the Guards had broken through) had ceased to exist and his left was becoming very insecure as a result of a renewed attack by 34th US Infantry Division and Coldstream Guards. At first light on the 10th Aprik , 34th US Division finally captured the Djebel Haouareb ridge. During the protracted fighting 34th US Division’s casualties, surprisingly, were not so heavy as in their previous action at Fondouk. Taking both together, however, the division lost 36 men and suffered 733 wounded – more than at any other time during the Tunisian campaign. Most of the casualties had shrapnel wounds and some senior officers fought on for hours in the front line after being hit. ‘We had some British tank casualties,’ reported the medical staff, ‘the heroism of these boys was amazing. You couldn’t make them complain even when you had to strip the burned skin off their hands and faces.’

By morning on 10 April, when ‘Pip’ Roberts drove elements of 6th British Armoured Brigade through heavy dust storms onto the Kairouan plain, most of the enemy had slipped away through the Fondouk Pass apart from a rearguard set to delay the pursuit, sometimes using captured Russian anti-tank guns. Late in the afternoon the Lothians and 16/5th Lancers were sweeping along the southern side of the main Fondouk-Kairouan highway when they caught up with the stragglers. In failing light they shot up an anti-tank screen, killing many of the gun crews and leaving the wrecked muzzles of four German 88 mm guns and 16 lighter anti-tank guns pointing aimlessly skywards. Out on the vast plain glared the fiery torches of seven burning M13/40 Italian tanks.

Back at the Fondouk Pass, McQuillin arrived from the south with 1st US Armored CC A, where he met units of the 168th US Infantry Regiment, both 24 hours too late to intercept the enemy’s retreat which went on all next day. Following close behind under the cloudless sky, a scout car, two Jeeps and a photographer of 1st Derbyshire Yeomanry entered Kairouan unopposed at 1100 hours.

Seen from a distance the white velvet of the town’s beautiful fluted domes seemingly floated over a scarlet carpet of poppies, but many Eighth Army troops were less than overwhelmed: ‘Today we pass through the holy city of Kairouan, the City of a Hundred Mosques, but to us it looked just the usual w… town,’ commented Sergeant Harris of a 22nd Armoured Brigade tank unit. The last truck out was crammed with Italians. Before leaving the Germans systematically booby-trapped many buildings, blew up the water supply and destroyed an electric power station.

Earlier on the 11th, C Squadron of 1st Derbyshire Yeomanry, ranging 20 miles south-east of the town, met Lieutenant Richardson’s troop of 12th Lancers, which seemed to specialize in these things. Again the encounter between First and Eighth Armies was downbeat, marked only by a few jokes and good-natured oaths on each side.

Advancing north and north-west the next day with orders to cut off the enemy on the Eastern Dorsale, Keightley’s mass of tanks missed out until late that evening when the Lothians’ B Squadron and 16/5th Lancers caught up with a fleeing German truck column. ‘Of the lorries all that remained was twisted metal, shattered windscreens, charred woodwork and tyres burnt to a fine ash. Both sides of the road and the road itself was littered with parts of vehicles, equipment, burnt-out ammunition cases and all the medley of burnt clothing, discarded arms, steel helmets and occasional dead that accompany a rout.’ Beside the roadside were German prisoners , more than 200 were captured. One badly-wounded youngster was, ‘crying piteously behind his thick-lensed spectacles.’

The failure to encircle and destroy First Italian Army before it settled behind the Enfidaville position exacerbated swelling resentment between the Allies. Opinion at 18th Army Group was extremely critical of the Americans’ recent performance. Alexander talked about their ‘Blah-Blah,’ thought them ‘crashing bores,’ and, while their hospitality and generosity were boundless, considered their supposed business efficiency and hustle to be ‘pure baloney.’ Lieutenant-General McCreery dismissed the ‘Fondouk fighters’ who in a week would be claiming they had taken Fondouk and Kairouan whereas all they had done was retreat. 1st US Armored Division consisted of ‘Ward’s Warriors’ who had captured nothing.

Such criticism was common throughout Eighth Army, from Montgomery down to the lowest ranks. Alan Moorehead, meeting the Eighth Army’s vanguard, saw a sergeant lean from the turret of his sand-coloured armoured car: ‘Who are you?’

‘The First Army’

‘Then you can go home now,’ was the response. More typical was a gunner’s shouted comeback when passed by American troops giving the Eighth Army men a two-fingered salute: ‘Going to f…k up another front, I suppose.’

Unfortunately, when Crocker gave what he thought was a strictly private and off-the-record analysis of recent fighting and the part played by Ryder’s division to a group of visiting Americans, his comments leaked out to press correspondents. The news soon got back to the United States and was magnified into blanket condemnation which accused the 34th US Division of such poor training and inefficiency that its troops had been late on their start line and unable to take their objectives; indeed, they could only be trusted to clean up battlefields.

Ryder protested loudly that Crocker’s plan had been badly flawed. Deeply suspicious of the British at Fondouk, he maintained his troops had not been expendable merely to allow 6th Armoured through the pass unscathed. Having ordered that any criticism of his own performance was not to be suppressed, Eisenhower was enraged to discover his censors had extended this to all units and allowed Crocker’s scathing indictment of the 34th’s shortcomings to become public. Firing his chief ‘fool censor’ (General McClure) the C-in-C immediately began a publicity counter-offensive to restore to the public an image of Allied unity before the final push for Tunisia.

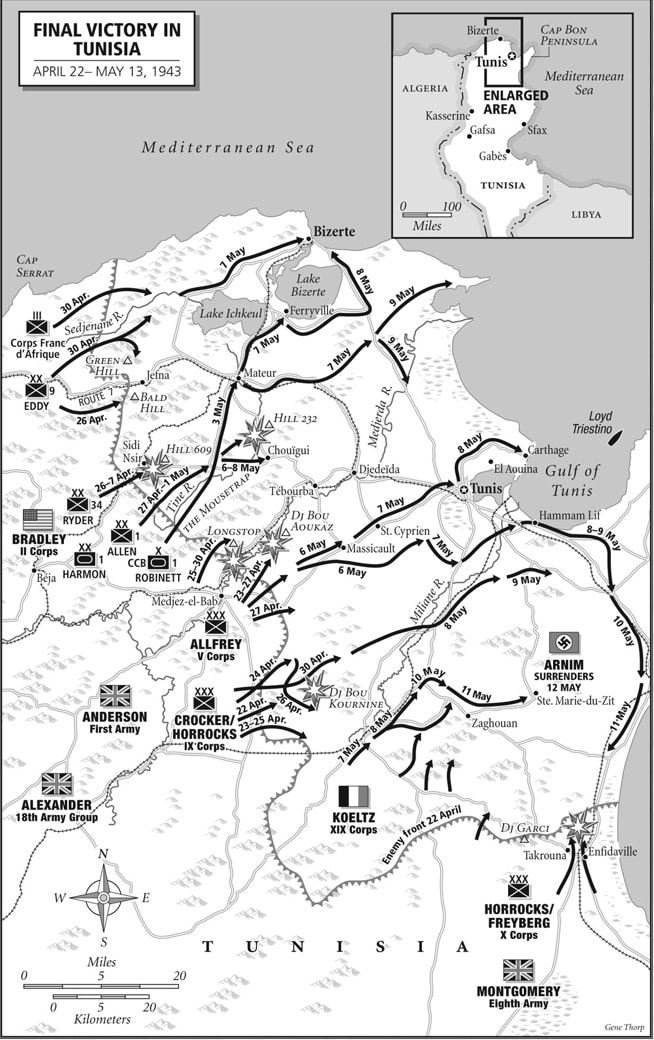

That could not be long delayed. In the north Koeltz’s French 19th Corps had broken through the Eastern Dorsale after heavy fighting, losing the inspirational General Welvert, commander of the Constantine Division, killed on the last day (10 April) before the Germans withdrew. The French moved north-east from Pichon with the object of taking Djebel Mansour and dominating high ground around Pont du Fahs. On the 13th they linked up with the most westerly units of Horrocks’ 10th Corps. By then Anderson had pressed forward on the front extending from Sedjenane southwards to the road running from Oued Zarga to Medjez. The task of forcing that road open as a preliminary to the final drive on Tunis fell to Evelegh’s 78th Division.

Before undertaking that, however, Evelegh was also ordered to mount a limited offensive and regain Sedjenane. Brigadier Flavell’s 1st Battalion (1st Parachute Brigade) had been left holding ‘Bowler Hat’, near Tamera. He was to help free the main coastal road axis running from Tabarka through Sedjenane to Mateur – and thence either to Bizerte or Tunis – by diverting attention from the attack put in by two of Evelegh’s infantry brigades, the 36th and 138th, on his right, just south of the road. The whole of Freeman-Attwood’s 46th (North Midland) Infantry Division’s artillery and a tabour of Goums were in support.

At 2200 hours on 27 March, a massive barrage of shells shrieked and moaned over the heads of the advancing paratroopers. 1st Battalion, passing 3rd Battalion on Bowler Hat, made good progress against moderate opposition from the 10th Bersaglieri Regiment, whom the Goums slaughtered in great numbers. An Italian colonel hastily surrendered, willingly handing over his sword but insisting on keeping his little dog.

On the left, 2nd Parachute Battalion advanced into an unsuspected minefield and ran into Witzig’s Fallschirmjägers, who held high, wooded and rocky ground. Frost’s men gradually worked their way onto a plateau, not far below the crest. An unfortunate German, blundering into their positions, screamed in pain when seized in a powerful arm-lock by Frost’s signal sergeant. ‘Put that man down will you Sergeant,’ called Frost. Back came the instant reply: ‘Oh, I can’t do that sir, I’ve never had one before!’

When daylight came the paratroopers discovered they were on a false crest, well short of their objective. Clinging on to prevent the brigade’s entire position being lost, they were plastered with concentrated machine-gun fire, artillery and mortar shells making it impossible to evacuate the wounded. Ordering fixed bayonets, Frost sounded a blast on his hunting horn. ‘Waho Mohammed’ (British paratroopers battle cry) they shouted as supporting guns and mortars suddenly poured fire into the enemy while the paratroopers broke cover. At the same moment B Company and part of 1st Battalion caught the Germans in a pincer-grip higher up the hill, just missing the redoubtable Major Witzig himself.

Doused by ‘friendly’ artillery fire, B Company suffered further casualties. Dazed and heavily depleted, the remaining 150 survivors had to be strengthened by a company from 3rd Battalion. That night, in pelting rain and pitch darkness, the ‘Red Devils’ clawed their way up again through a hail of fire while the Germans pulled back to their positions on Green and Bald Hills, which they had held in February. By 1145 hours next day, the Parachute Brigade was astride the main road near Tamera and 16 days later was relieved by troops of the 9th US Division.

They arrived to take over with much swagger and fuss. Inquiring if it were necessary for the Americans to wear helmets in what was now virtually a rest area, Lieutenant-Colonel Pearson of 1st Parachute Battalion was told by their CO: ‘If George S. Patton says you wear your steel helmet, you wear it. If George S. Patton says attack, we attack, and that’s where the goddamn fuck-up begins.’ Pearson was inclined to agree.

The corps commander, 5th British Corps General Allfrey, came to see the paratroopers before they set off for Bou Farik, there to rest and re-organize before the invasion of Sicily. In five months, the brigade had suffered 1,700 wounded, killed and missing. As their train passed the biggest prisoner-of-war camp in North Africa there came flocking to the wire thousands of Germans who, seeing the red berets, cheered and cheered. ‘It was our nicest tribute,’ commented John Frost.

These were few in number. Most paratroopers were furious at their treatment, used as infantry without adequate equipment and in the line continually since 26 January. Again and again they had fought off superior numbers and received no credit at all. Several war correspondents who knew the truth wrote to Alexander asking for the ban on reporting their activities to be lifted. The last thing the Army authorities wanted – or Churchill for that matter – was a decline in recruiting and questions in the House of Commons. The ban remained.

Resistance to the other prong of Evelegh’s attack had been patchy. ‘Swifty’ Howlett’s 36th Brigade, led by 5th Buffs, broke through the German defences to threaten the Fallschirmjäger left flank. On a wider sweep to the south, Brigadier G.P. Harding’s 138th Brigade advanced behind 6th Lincolns until dense scrub became too thick even for the supporting Churchills from the North Irish Horse. Nothing daunted, a violent series of bayonet attacks by 6th Battalion, York and Lancs, resulted in the capture of the ore mine at Sedjenane. They became instant heroes in the British Press, including Lieutenant-Colonel Joe Kendrew, former England rugby forward, who got the first of his four DSOs for outstanding leadership.

By the last day of March, 46th Reconnaissance Regiment (46th Infantry Division) had re-taken Sedjenane after 8th Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders battered their way to the outskirts of the village. Around them was a world of untidy and pitted earth, smashed and burned vehicles littering the roadside, thousands upon thousands of shell cases, petrol tins and mines in the growing fields of corn and over everything the heavy smell of dead flesh.

Having recaptured the ground lost during Operation Ausladung, First Army was beginning to show its mettle. The 78th British Division was concentrating at Teboursouk, ready to secure the second part of Anderson’s limited objectives. Coming down from the north, 36th Brigade was united with ‘Copper’ Cass’s 11th Brigade, which had been holding Oued Zarga, and the newly-arrived 38th Irish Brigade. They were to attack ridges and peaks of the jumbled mass of high land running almost due east to west on the north side of the Béja-Medjez highway and take the villages of Toukabeur, Chaouach and Heidous as well as the hills, some of them rising to 3,000ft, including Djebels Ang, el Mahdi and Tanngoucha.

Evelegh used a model of the mountains to brief his COs with the First Army commander also present. ‘The plan’s all right but will the troops fight?,’ asked Anderson. ‘Well, sir,’ replied Evelegh, ‘one can only plan in the expectation that they will.’

Major-General Hawkesworth’s 4th British Infantry (Mixed) Division had recently arrived in North Africa and was sent straight to the front to relieve 46th Infantry Division at Hunt’s Gap. Its task was to put in a noisy diversion while Evelegh’s brigades pushed ahead in a 12-mile arc, supported by 184 guns extending over a five-mile front south of the Medjez road. At 0345 hours on 7 April they suddenly opened their barrage and as soon as this lifted, the infantry rose from their start lines and began climbing, on the left men of 38th Brigade, in the centre the 36th and 11th on the right.

The Irish Brigade’s first objective was Djebel el Mahdi, a whale-backed ridge 1,400ft high, four miles long and liberally strewn with mines. By dawn the senior regiment, the Inniskillings, had driven the enemy off the southern end, losing their CO in the process. Following up in daylight, the Royal Irish got through unpleasant thorn scrub at the footings of Djebel Mahdi and discovered strewn bodies of ‘Skins’ who had charged straight over the top of a minefield in their preliminary attack. Carefully making their way through taped gaps they waited behind a boiling grey-black cloud of dust and flame as the gunners hit the crest of the ridge and, shortly after noon, went in with rifle and bayonet. Within three hours the Irish Fusiliers had cleared the rest of the hill. ‘The sense and the emotive feelings of triumph with a flying enemy before one are like nothing I have known on any other occasion in this world,’ remarked John Horsfall. Four miles or so inside the enemy positions, with the opposition not yet cleared from their flanks, they dug in as the enemy hit back with self-propelled guns. Sweeping up in support, 2nd Hampshires and 16th Durham Light Infantry found the going difficult.

In the centre, 5th Buffs and 6th Queen’s Own Royal West Kents were on their objectives by evening despite suffering casualties from enemy artillery and dive-bombing. To their right 1st East Surreys was making good progress towards the village of Toukabeur. Much was made possible by the startling climbing ability of the Churchills of the North Irish Horse. Advancing up seemingly impossible gullies and crevices in the limestone cliffs they covered the infantry who inched forward until they could hurl grenades into the enemy’s gun positions. Next day they were crawling up 1,800 feet of Djebel Bech Chekaou while the infantry struggled to stay upright in a howling gale.

Ahead, to their left, in failing light and still lashed by raging winds, 5th Buffs managed to advance onto Point 667 (2,188ft) dominating the western range whose last several hundred feet were too precipitous even for the tanks. Already a message had flashed from the East Surreys: ‘Touk is took’ – they were in the village of Toukabeur. The following day, the West Kents forced a passage along the mountain ridges and Chaouach – ‘Charwash’ to the troops – was taken by a combination of East Surreys, Lancashire Fusiliers and tanks of 142nd Royal Armoured Corps.

Outnumbered and poorly-supported the Germans hardly stood a chance in these western peaks but troops from 1st Battalion, 962nd German Regiment, and 3rd Battalion, 756th German Mountain Infantry Regiment, resisted with great courage, grudgingly giving space and fighting every step of the way.