Resources

-Memoirs - Field Marshall Montgomery

-The Battle of North Africa , El Alamein , Turning Point of World War II - Glyn Harper

-Pendelum of War , Three Battles of Alamein - Niall Barr

-The World Arms (Readers Digest)

-Eighth Army’s Greatest Victories - Adrian Turner

-Britain’s War in Desert - David Braddock

-Howard Kippenberger , Dauntless Spirit - Denis Mclean

-Foxes of Desert - Paul Carell

-Rommel Papers - Lidell Hart

-Montgomery , Master of Battle 1942-1944 - Nigel Hamilton

-The Alexander Memoirs - Field Marshal Alexander

Memoirs (Field Marshal Montgomery) :

ALAM HALFA had interfered with the preparations for our own offensive, and delayed us. But the dividend in other respects had been tremendous. Before Alam Haifa there was already a willingness from below to do all that was asked, because of the grip from above. And for the same reason there was a rise in morale, which was cumulative. I think officers and men knew in their hearts that if we lost at Alam Haifa we would probably have lost Egypt. They had often been told before that certain things would happen; this time they wanted to be shown, not just to be told. At Alam Haifa the Eighth Army had been told, and then shown; and from the showing came the solid rocklike confidence in the high command, which was never to be lost again.

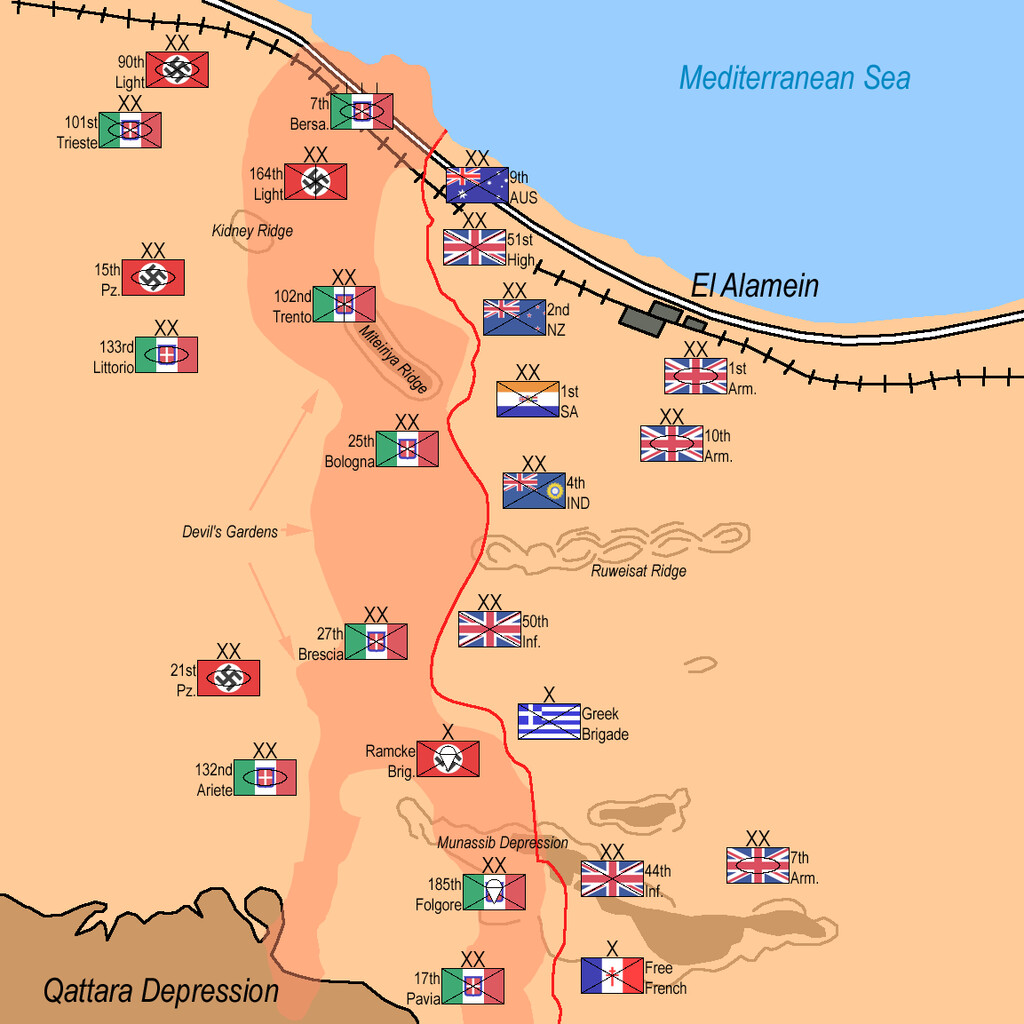

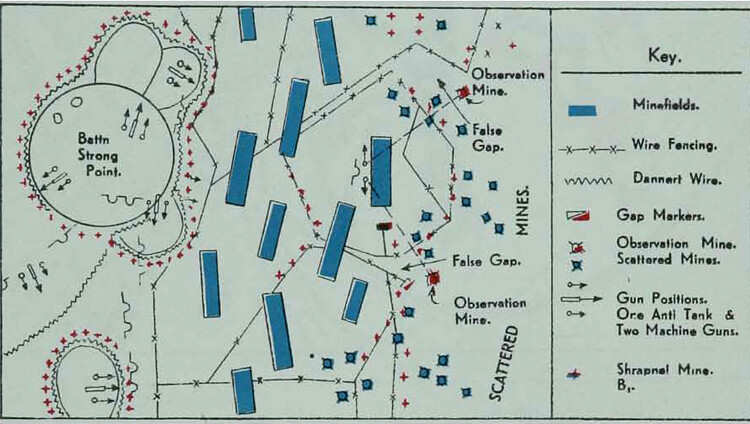

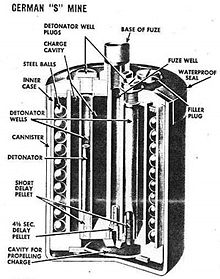

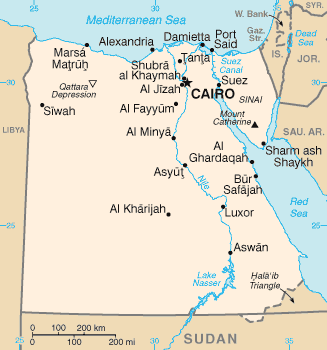

The basic problem that confronted us after the Battle of Alam Haifa was a difficult one. We were face to face with Rommel’s forces between the sea and the Qattara Depression, a distance of about 45 miles. The enemy was strengthening his defences to a degree previously unknown in the desert, and these included deep and extensive minefields. There was no open flank. The problem was: First— to punch a hole in the enemy positions. Second— to pass 10 Corps, strong in armour and mobile troops, through this hole into enemy territory. Third— then to develop operations so as to destroy Rommel’s forces. This would be an immense undertaking. How could we obtain surprise? It seemed almost impossible to conceal from the enemy the fact that we intended to launch an attack. I decided to plan for tactical surprise, and to conceal from the enemy the exact places where the blows would fall and the exact times. This would involve a great deception plan and I will describe later some of the measures we took.

Next, a full moon was necessary. The minefield problem was such that the troops must be able to see what they were doing. A waning moon was not acceptable since I envisaged a real “dog-fight” for at least a week before we finally broke out; a waxing moon was essential. This limited the choice to one definite period each month. Owing to the delay caused to our preparations by Rommel’s attack, we could not be ready for the September moon and be sure of success. There must be no more failures. Officers and men of the Eighth Army had a hard life and few pleasures; and they put up with it. All they asked for was success, and I was determined to see they got it this time in full measure. The British people also wanted real success; for too long they had seen disaster or at best only partial success. But to gain complete success we must have time; we had to receive a quantity of new equipment, and we had to get the army trained to use it, and also rehearsed in the tasks which lay ahead. I had promised the Eighth Army on arrival that I would not launch our offensive till we were ready. I could not be ready until October. Full moon was the 24th October. I said I would attack on the night of 23 rd October, and notified Alexander accordingly. The come-back from Whitehall was immediate. Alexander received a signal from the Prime Minister to the effect that the attack must be in September, so as to synchronise with certain Russian offensives and with Allied landings which were to take place early in November at the western end of the north African coast (Operation TORCH). Alexander came to see me to discuss the reply to be sent. I said that our preparations could not be completed in time for a September offensive, and an attack then would fail: if we waited until October, I guaranteed complete success. In my view it would be madness to attack in September. Was I to do so? Alexander backed me up whole-heartedly as he always did, and the reply was sent on the lines I wanted. I had told Alexander privately that, in view of my promise to the soldiers, I refused to attack before October; if a September attack was ordered by Whitehall, they would have to get someone else to do it. My stock was rather high after Alam Haifa! We heard no more about a September attack.

THE PLAN

The gossip is, so I am told, that the plans for Alamein, and for the conduct of the war in Africa after that battle, were made by Alexander at G.H.Q. Middle East and that I merely carried them out. This is not true. All the plans for Alamein and afterwards were made at Eighth Army H.Q. I always kept Alexander fully informed; he never commented in detail on my plans or suggested any of his own; he trusted me and my staff absolutely. Once he knew what we wanted he supported us magnificently from behind; he never refused any request; without that generous and unfailing support, we could never have done our part. He was the perfect Commander-in-Chief to have in the Middle East, so far as I was concerned. He trusted me.

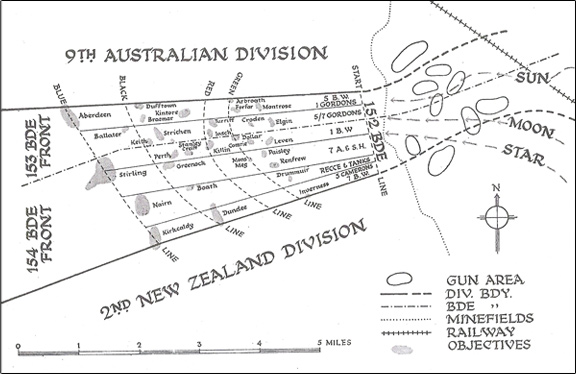

The initial plan was made in the first days of September; immediately after the Battle of Alam Haifa was over. This plan was to attack the enemy simultaneously on both flanks. The main attack would be made by 30 Corps (Leese) in the north and here I planned to punch two corridors through the enemy defences and minefields. 10 Corps (Lumsden) would then pass through these corridors and would position itself on important ground astride the enemy supply routes; Rommel’s armour would have to attack it, and would, I hoped, be destroyed in the process. The sketch map shows the plan. It will be seen that the defended area, including minefields, through which the northern corridor was to be punched was 5 miles deep.

In the south, 13th Corps (Horrocks) was to break into the enemy positions and operate with 7th Armoured Division with a view to drawing enemy armour in that direction; this would make it easier for 10th Corps to get out into the open in the north. 13th Corps was not to suffer heavy casualties, and in particular 7th Armoured Division was to remain “in being” and available for the mobile operations after the break-out had been achieved. It will be noted that my plan departed from the traditional desert tactics of staging the main offensive on the south or inland flank, and then wheeling towards the sea. I considered that if my main attack was in the south there was only one direction it could take after the break-in—and that was northwards. The fact that a certain tactic had always been employed by all commanders in the desert seemed to me a good reason for doing something else. I planned to attack neither on my left flank nor on my right flank, but somewhere right of centre; having broken in, I could then direct my forces to the right or to the left as seemed most profitable. This decision was not popular with the staff at G.H.Q. and pressure was brought on my Chief of Staff to influence me to change my mind. Alexander never joined in the argument; he understood all my proposals and backed them to the hilt.

I was watching the training carefully and it was becoming apparent to me that the Eighth Army was very untrained. The need for training had never been stressed. Most commanders had come to the fore by skill in fighting and because no better were available; many were above their ceiling, and few were good trainers. By the end of September there were serious doubts in my mind whether the troops would be able to do what was being demanded; the plan was simple but it was too ambitious. If I was not careful, divisions and units would be given tasks which might end in failure because of the inadequate standard of training. The Eighth Army had suffered some 80,000 casualties since it was formed, and little time had been spent in training the replacements.

The moment I saw what might happen I took a quick decision. On the 6th October, just over two weeks before the battle was to begin, I changed the plan. My initial plan had been based on destroying Rommel’s armour; the remainder of his army, the un-armoured portion, could then be dealt with at leisure. This was in accordance with the accepted military thinking of the day. I decided to reverse the process and thus alter the whole conception of how the battle was to be fought. My modified plan now was to hold off, or contain, the enemy armour while we carried out a methodical destruction of the infantry divisions holding the defensive system. These un-armoured divisions would be destroyed by means of a “crumbling” process, the enemy being attacked from the flank and rear and cut off from their supplies. These operations would be carefully organised from a series of firm bases and would be within the capabilities of my troops. I did not think it likely that the enemy armour would remain inactive and watch the gradual destruction of all the unarmoured divisions; it would be launched in heavy counter-attacks. This would suit us very well, since the best way to destroy the enemy armour was to entice it to attack our armour in position. I aimed to get my armour beyond the area of the “crumbling” “crumbling” operations. I would then turn the enemy minefields to our advantage by using them to prevent the enemy armour from interfering with our operations; this would be done by-closing the approaches through the minefields with our tanks, and we would then be able to proceed relentlessly with our plans. The success of the whole operation would depend largely on whether 30th Corps could succeed in the “break-in” battle and establish the corridors through which the armoured divisions of 10th Corps must pass. I was certain that if we could get the leading armoured brigades through the corridors without too great delay, then we would win the battle. Could we do this? In order to make sure, I planned to launch the armoured divisions of 10th Corps into the corridors immediately behind the leading infantry divisions of 30th Corps and before I knew the corridors were clear. Furthermore, I ordered that if the corridors were not completely clear on the morning of D+1, the 24th October, the armoured divisions would fight their own way out into the open beyond the western limit of the minefields. This order was not popular with the armoured units but I was determined to see that it was carried out to the letter.

It will be seen later how infirmity of purpose on the part of certain senior commanders in carrying out this order nearly lost us the battle.

I mentioned in Chapter 8 that there was a Major Williams on my intelligence staff who appeared to me to be of outstanding ability. To all who served with me in the war he was known always as Bill Williams. In a conversation one day about this time, he pointed out to me that the enemy German and Italian troops were what he called “corsetted”; that is, Rommel had so deployed his German infantry and parachute troops that they were positioned between, and in some places behind, his Italian troops all along the front, the latter being unreliable when it came to hard fighting. Bill Williams’s idea was that if we could separate the two we would be very well placed, as we could smash through a purely Italian front without any great difficulty. This very brilliant analysis and idea was to be a major feature of the master plan for the “crumbling” operations, and it paved the way to final victory at Alamein.

THE DECEPTION PLAN

The object of the deception plan was twofold:

(a) To conceal from the enemy as long as possible our intention to take the offensive.

(b) When this could no longer be concealed, to mislead him about both the date and the sector in which our main thrust was to be made.

This was done by the concealment of real intentions and real moves in the north, and by advertising false signs of activity in the south.

The whole deception was organised on an “army” basis; tremendous attention to detail was necessary throughout, since carelessness in any one area might have compromised the whole scheme. To carry out such a gigantic bluff in the time available required detailed planning, considerable quantities of labour and transport, mass production of deception devices at the base, a large camouflage store with trained staff, and the co-ordinated movement of many hundreds of vehicles into selected areas. Because all these essentials were provided the scheme was entirely successful, and great credit is due to the camouflage organisation in the Middle East at the time.

A feature of the “visual deception” was the creation and continued preservation of the layout and density of vehicles required for the assault in 30 Corps sector in the north; this was achieved by the 1st October by the placing in position of the necessary dummy lorries, guns, ammunition limbers, etc. During the concentration of attacking divisions just before the day of the attack, the dummies were replaced at night by the actual operational vehicles. The rear areas, whence the attacking divisions and units came, were maintained at their full visual vehicle density by the erection of dummies as the real vehicles moved out. The reason for all this visual deception was that enemy air photographs should continue to reveal the same story. The coordinating brain behind this part of the plan was Charles Richardson, a very able officer in the planning staff of Eighth Army H.Q. (now Major-General C. L. Richardson, recently Commandant of the Military College of Science).

In preparation for the offensive, dumps had to be made in the northern sector. For example, a large dump was created near the station of Alamein. This was to contain 600 tons of supplies, 2000 tons of P.O.L. (petrol, oil, lubricants), and 420 tons of engineer stores. It was of the utmost importance that the existence of these dumps should not become known to the enemy. The site was open and featureless except for occasional pits and trenches. Disguise provided the most satisfactory method of hiding the dumps, and the whole endeavour was a triumph for the camouflage organisation.

Another example I will quote was the dummy pipeline in the south to cause the enemy to believe the main blow would be delivered on that flank. It was started late in September and progress in the work was timed to indicate its completion early in November. The dummy pipeline was laid for a length of about 20 miles, from a point just south of the real water point at Bir Sadi to a point 4 miles east of Samaket Gaballa. The pipe-trench was excavated in the normal way. Five miles of dummy railway track, made from petrol cans, were used for piping. The “piping” was strung out alongside the open trench. When each 5-mile section of the trench was filled in, the “piping” was collected and laid out alongside the next section. Dummy pump houses were erected at three points; water points and overhead storage reservoirs were made at two of these points. Work began on the 26th September and ceased on the 22nd October; it was carried out by one section of 578 Army Troops Company.

There were of course other measures such as the careful planting of false information for the enemy’s benefit, but I have confined this outline account to visual deception in which camouflage played the major part. The whole plan was given the code name BERTRAM and those responsible for it deserve the highest praise: for it succeeded.

The RAF was to play a tremendous part in this battle. Desert Air Force aimed to gain gradual ascendancy over the enemy fighters, and to have that ascendancy complete by the 23rd October. On that day the RAF was to carry out blitz attacks against enemy airfields in order to finish off the opposing air forces, and particularly to prevent air reconnaissance. At zero hour the whole bomber effort was to be directed against the enemy artillery, and shortly before daylight on the 24th October I hoped the whole of the air effort would be available to co-operate intimately in the land battle, as our fighter ascendancy by that time would be almost absolute.

I issued very strict orders about morale, fitness, and determined leadership, as follows:

ORDERS ABOUT MORALE: ISSUED ON THE 14TH SEPTEMBER

“This battle for which we are preparing will be a real rough house and will involve a very great deal of hard fighting. If we are successful it will mean the end of the war in North Africa, apart from general ‘clearing-up’ operations; it will be the turning point of the whole war. Therefore we can take no chances. Morale is the big thing in war. We must raise the morale of our soldiery to the highest pitch; they must be made enthusiastic, and must enter this battle with their tails high in the air and with the will to win. There must in fact be no weak links in our mental fitness. But mental fitness will not stand up to the stress and strain of battle unless troops are also physically fit. This battle may go on for many days and the final issue may well depend on which side can best last out and stand up to the buffeting, the ups and downs, and the continuous strain of hard battle fighting.

I am not convinced that our soldiery are really tough and hard. They are sunburnt and brown, and look very well; but they seldom move anywhere anywhere on foot and they have led a static life for many weeks. During the next months, therefore, it is essential to make our officers and men really fit; ordinary fitness is not enough, they must be made tough and hard.”

ORDERS ABOUT LEADERSHIP: ISSUED ON THE 6TH OCTOBER

“This battle will involve hard and prolonged fighting. Our troops must not think that, because we have a good tank and very powerful artillery support, the enemy will all surrender. The enemy will not surrender, and there will be bitter fighting. The infantry must be prepared to fight and kill, and to continue doing so over a prolonged period. It is essential to impress on all officers that determined leadership will be very vital in this battle, as in any battle. There have been far too many unwoundcd prisoners taken in this war. We must impress on our officers, n.c.o.s and men that when they are cut off or surrounded, and there appears to be no hope of survival, they must organise themselves into a defensive locality and hold out where they are. By doing so they will add enormously to the enemy’s difficulties; they will greatly assist the development of our own operations; and they will save themselves from spending the rest of the war in a prison camp. Nothing is ever hopeless so long as troops have stout hearts, and have weapons and ammunition. These points must be got across now at once to all officers and men, as being applicable to all fighting.”

ORDERS REGARDING SECRECY

It was clear to me that we could not inform the troops about our offensive intentions until we stopped all leave and kept them out in the desert. I did not want to create excitement in Alexandria and Cairo by stopping leave with an official announcement. I therefore ordered as outlined below. Officers and men were to be brought fully into the operational picture as follows:

On the 21st October a definite stop was to be put to all journeys by officers or men to Alexandria, or other towns, for shopping or other reasons.

On the 21 st October unit commanders were to stop all leave, quietly and without publishing any written orders. They were to give as the reason that there were signs the enemy might attack in the full-moon period, and that we must have all officers and men present.

What it amounted to was that by the 21st October everyone, including the soldiers, would be fully in the operational picture; no one could leave the desert after that.

There was one exception. I ordered that troops in the foremost positions who might be raided by the enemy and captured, and all troops who might be on patrol in no-man’s-land, were not to be told anything about the attack till the morning of the 23 rd October: which was D-Day.

GROUPING FOR THE BATTLE This was the grouping of divisions opf Eighth Army for the beginning of the battle:

10th Corps (commanded by General Lumdsen in reserve) : 1st Armd Division , 10th Armd Division

13th Corps (commanded by General Horrocks in southern flank of Alamein line) : 44th Home Countries Division , 50th Northumberland Infantry Division , 7th Armd Division , 1st Free French Brigade and 1st Free Greek Brigade

30th Corps (commanded by General Leese on northern flank that would launch main attack LIGHTFOOT) : 51st Highland Division , 9th Australian Division , 2 New Zealand Division , 1st South African Division , 4th Indian Division , 23rd Armored Brigade (with Valentine tanks)

FINAL ADDRESS TO SENIOR OFFICERS

This was to be an “Army” battle, fought on an Army plan, and controlled carefully from Army H.Q. Therefore every commander down to the Lieut.-Colonel level must know the details of my plan, how I proposed to conduct the fight, and how his part fitted in to the master plan. Only in this way could perfect co-operation be assured. I therefore assembled these commanders and addressed them on the following dates:

30th Corps 19 October

13th Corps 19 October

10th Corps 20 October

I still have the notes I used for the three addresses: written in pencil in my own handwriting. I reproduce them here. I took a risk in saying “Whole affair about 12 days.” It will be seen that I originally wrote 10 days, and then erased the 10 and wrote 12. 12 was the better guess. It will also be seen in para. 2 that I couldn’t spell “Rommel” properly. Rough notes used by me for my address to all senior officers before the Battle of Alamein (code name “Lightfoot”)

ADDRESS TO OFFICERS—“LIGHTFOOT”

- Back history since August. The Mandate; my plans to carry it out; the creation of 10 Corps.Leadership—equipment—training.

- Interference by Rommell on 31 Aug.

- The basic framework of the Army plan for Lightfoot as issued on 14 Sep. To destroy enemy armour. 4. Situation in early October. Untrained Army.Gradually realised that I must recast the plan so as to be within the capabilities of the troops.

The new plan; the “crumbling” operations.A reversal of accepted methods. - Key points in the Army plan. Three phases The dog-fight, and “crumbling” operations.The final “break” of the enemy.

30th Corps - break in (fighting for position and tactical advantage)

10th Corps - break out

13th Corps - break in (fighting for position and tactical advantage) - The enemy : His sickness among troops ; low unit strengths; small stocks of petrol

Morale is good, except possibly Italians. - Ourselves

Immense superiority in guns, tanks, men. Can fight a prolonged battle, morale top of the line - General conduct of the battle : Methodical progress; destroy enemy part by part, slowly and surely.

Shoot tanks and shoot Germans.,

He cannot last a long battle; we can.

We must therefore keep at it hard; no unit commander must relax the pressure; Organise ahead for a “dog-fight” of a week. Whole affair about 10-12 days. —Don’t expect spectacular results too soon.

-

Operate from Firm Bases

Quick Re Organisation at the Objectives

Keep Balanced

Maintain Offensive Eagerness

Keep Up PressureIf we do all of these above , victory is certain

-

Morale—measures to get it. Addresses. Every soldier in the Army a fighting soldier. No non-fighting man. All trained to kill Germans. My message to the troops.

-

The issues at stake.

-

The troops to remember what to say if they are captured. Rank, name, serial number.

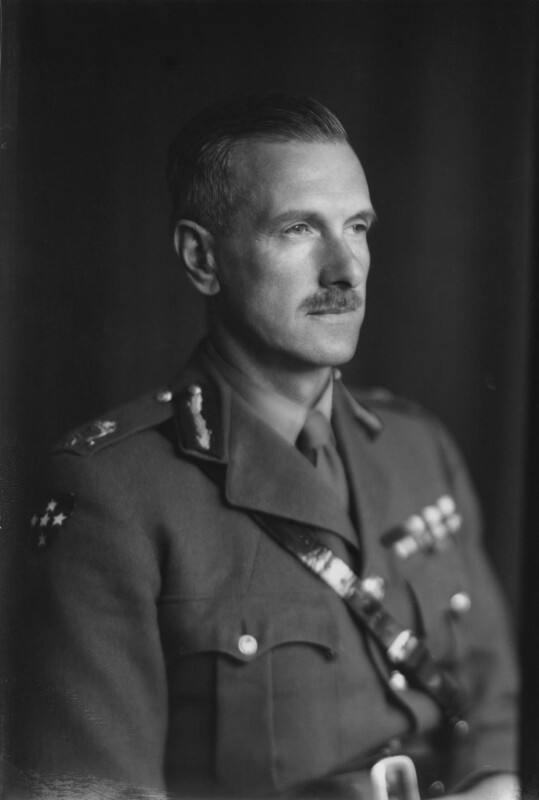

Bernard Law Montgomery