25 DIE WHEN PLANE CRASHES IN STORM

…

Sen. Lundeen Among Dead as Transport Plunges Into Field

…

Lovettsville, Va., Aug. 31 (UP) –

U.S. Sen. Ernest Lundeen of Minnesota and 24 other persons were killed today when a shiny new Pennsylvania Central Airlines transport crashed and exploded during a severe thunderstorm.

Some witnesses reported having seen indications of fire aboard the plane before it drove into a muddy field and burst into countless scattered pieces.

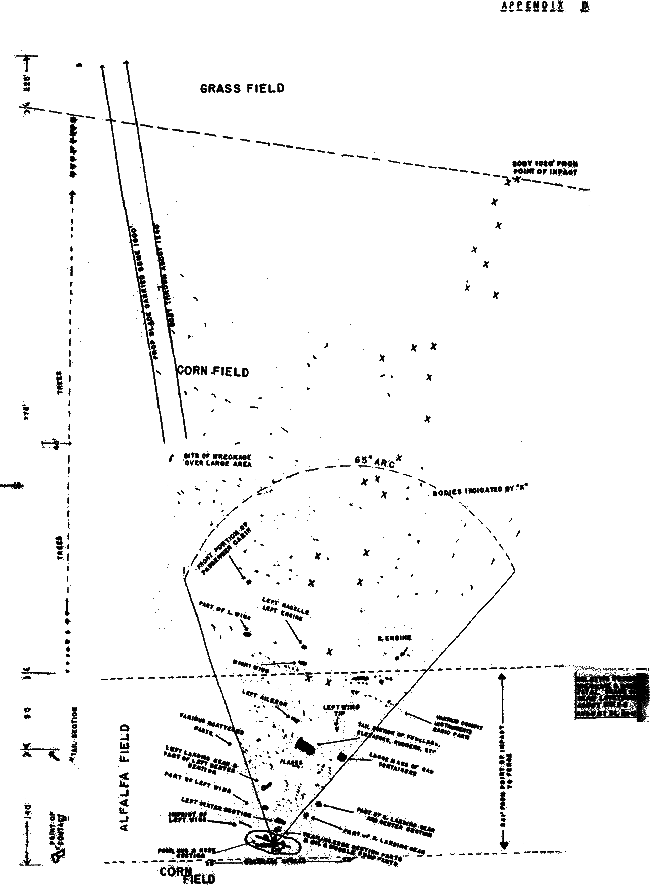

Several agreed that the impact brought an explosion and a burst of flame that lighted up the cloud-darkened countryside. Part of one body was hurled 2,000 feet from the wreckage.

It was the worst airplane accident in this country’s experience, the next worst one having killed 19 persons. It ended a no-fatality record by domestic airlines that lasted one year, five months and five days. It was the first fatal accident in PCA’s 13 years of operation.

Loaded to Capacity

The plane was loaded to capacity with passengers from Washington, D.C. It was bound for Pittsburgh, Akron, Cleveland and Detroit.

In addition to Senator Lundeen, a Farmer-Laborite who was one of the Senate’s most vigorous and outspoken members, there were many other government officers aboard. They included William Garbose, an attorney in the Justice Department’s Criminal Division; Joseph J. Pesci, a special agent of the Federal Bureau of Investigation; Miss Margaret Turner, a secretary in the FBI, and two Internal Revenue bureau men.

Federal investigators, headed by Chairman Harllee Branch of the Civil Aeronautics Board, speeded here from Washington, only about 50 miles away.

Hit Slight Knoll

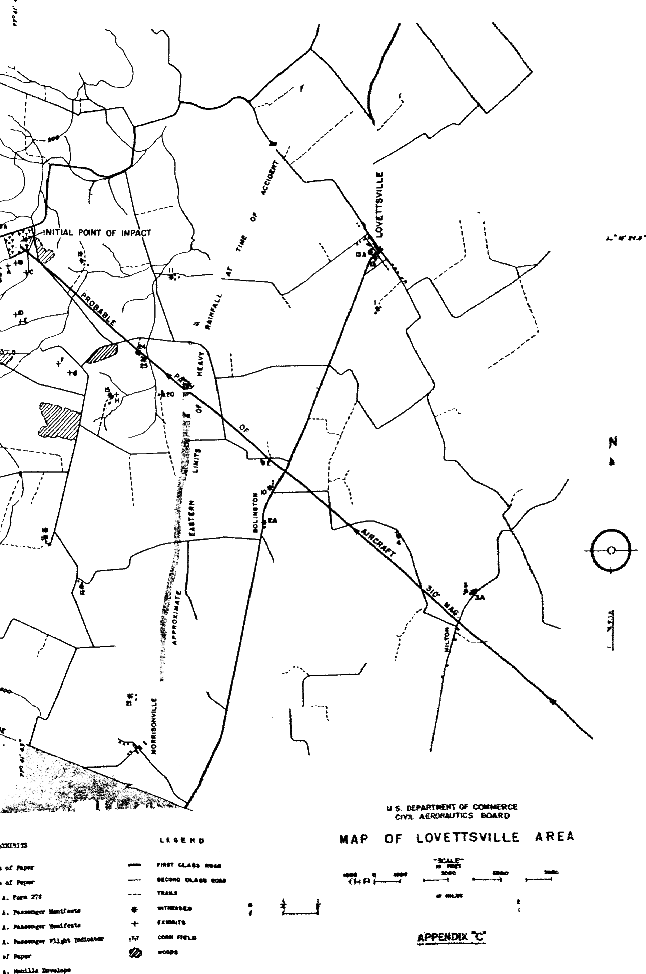

The plane left Washington at 3:18 p.m. (EDT). In little more than half an hour, it crashed on a gentle knoll in an alfalfa patch on the farm of Walter Bishop. The members of the Bishop family gave a graphic description of what they heard and saw during the seconds preceding the crash.

Mrs. Clarence Bishop said:

My husband was out on the front porch with the children watching the storm. All of a sudden there was a roar and a big crash. which lighted up the whole inside of the house with a bright flash. My husband pushed the children inside because we thought something was going to hit us. I never saw the plane.

Clarence Bishop said he thought that the pilot might have seen Short Hill Mountain up ahead of him and gunned the motors to circle and get over it.

Pilot Gunned Motors

William Insling, a dairyman living four miles from the scene of the crash, said:

Seems like this thing blasted out all at once. The pilot seemed to have given her the gun and then – Bang!.

Ernest Graham, who with other threshers had taken refuge, beside their machine during the storm, reported the mysterious evidence of fire preceding the crash. He was about half a mile from the point of crash.

As the plane swooped down over us we saw a piece of paper coming down and it was on fire. The rain was fierce then and it was out before it hit the ground.

Graham retrieved the charred paper and found it was a partially burned Pennsylvania Central Airlines form, carrying at the top in small letters “Form of PCA No. 252.” Beneath this heading was “Pennsylvania Central Airline Corp., Allegheny County Airport, Pittsburgh.” The remainder of the form was not legible.

No one actually saw the plane strike the ground, but the Bishop family and others near the scene agreed that there was an explosion. The fragments of the wreckage tended to conform this.

The plane crashed about 400 yards from the Bishop house. Fragments of the motor were blown over the house. A part of one body was 2,000 feet from where the motors were imbedded in the mud. The motors were mostly buried in mud, but pieces of pistons were found hundreds of feet away. One propeller was imbedded so deeply that two men could not budge it.

Bodies Widely Scattered

The bodies were scattered chiefly over a radius of 500 yards. Dr. John Gibson, Loudon County coroner, took charge of the almost impossible task of identification.

When investigators reached the scene tonight, oil flares illuminated the alfalfa field, which was roped off and placed under guard at orders of CAB inspectors.

Access to the scene was difficult. The storm, of cloudburst proportions, was called the worst this extreme northern part of Virginia has seen in 10 years. Many roads were blocked off due to washouts. Flickering oil flares marked great chasms in the roads.

M. Q. Crowder, a PCA traffic official, supervised collection of the plane’s mail cargo. It was placed in a heap near the wreckage, awaiting arrival of inspectors.

Federal inspectors will try to determine whether the storm or some trouble in the new Douglas DC-3 transport, a deluxe model the PCA recently put into service, was responsible. It was the worst since October 17, 1937, when a United Airlines plane carried 19 to death against the jagged Wasatch Peaks near Salt Lake City, Utah.

Donald Duff, PCA Washington traffic manager, said:

We don’t know what caused the accident. It is a mystery that may not be cleared up for months.

Battled Severe Storm

Apparently the plane went through a veritable maelstrom. Mrs. Bishop said that lightning flashed continually, the wind blew in gusts, and rain drove down in swirling clouds when she heard the roar of motors over her house like the sound of “a hundred fire engines.” Aviators speculated whether the plane might have been struck by lightning or smashed down to the earth by one of the great downdrafts that occur in thunderheads.

At the controls was one of the country’s veteran airline pilots, Capt. Lowell Scroggins, with 20 years of air transport flying to his credit and was known as a “1,000,000-mile pilot.”

Time of the crash was set at 3:40 p.m. (EDT). The big plane had been scheduled to leave Washington at 2:50 p.m. (EDT), but it delayed its departure to pick up a passenger from another plane. 20 minutes later, Captain Scroggins radioed from over Leesburg that all was well at 3,000 feet with the ground visible. Five minutes later, he would have been over Martinsburg, W. Va., and made a similar report. That report was never sent.

Frank Caldwell, chief of the investigation division of the CAB safety bureau, said that the pilot was on his course at the time of the accident. Caldwell said that he could not tell from a preliminary inspection what caused the accident.

Storm Knocks Out Plane

When the plane crashed at 3:40 p.m. (EDT), it took residents some hours to send word of the accident, due to the violence of the storm. Farmers who heard the crash made their way to the scene and then sought to use the telephone at John Kolb’s home. The storm had rendered it useless.

Bryce Winters, who was the first to reach the alfalfa patch, drove back over the slick, one-lane clay road to Leesburg and telephoned Washington that an airplane had crashed, but he could not tell anyone what kind of a plane and how many persons might have been killed.

Maryland State Police across the Potomac River investigated and informed Virginia Highway Patrolmen. This was a tedious process, because each trip to the field, requiring more than a mile of plodding through ankle-deep mud, took more than an hour.

E. J. Kyle and L. W. Hicks, postal inspectors, took charge of the mail tonight. They said it was intact.

No attempt was made to remove the bodies tonight. The rain had subsided at 11:00 p.m. (EDT), but it was too difficult to assemble the remains by the light of flares and flashlights.

List of Passengers

Pennsylvania Central Airlines reported tonight the following as the official passenger list of the Washington-Pittsburgh flight that crashed near Lovettsville, Va., today, killing 25 persons:

- Senator Ernest Lundeen (FLR-MN), Chevy Chase, Md.

- Mr. W. M. Burleson, 57 Look Lone Road, Richmond, Va.

- Dr. Charles D. Cole, 5305 41st St., N. W., Washington, D. C.

- E. J. Tarr, 1722 19th St., N. W., Washington, D. C.

- Miss M. Turner, Huddleston, Va.

- Miss C. Post, 1739 Kilburn Place, N. W., Washington, D. C.

- William Garbose, Department of Justice, Washington, D. C.

- Miss Evelyn Goldsmith, 1200 Euclid St., N. W., Washington, D. C.

- Miss Dorothy Boer, Foster Travel Service, Washington, D. C.

- Arthur Hollaway, Interstate Commerce Commission, Washington, D. C.

- E. G. Bowler, Department of Internal Revenue, Washington, D. C.

- Joseph J. Pesci, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Washington, D. C.

- Miss Naomi Colpo, 3621 Newark Street, N. W., Washington, D. C.

- A. E. Elliot, 3757 McKinley Street, N. W., Washington, D. C.

- Mrs. Ralph M. Hale, of Charlottesville, Va.

- Miss Mildred Chesser, 1739 M St., N. W., Washington, D. C.

- D. P. James, Interstate Commerce Commission, Des Moines, Iowa.

- H. J. Hofferth, Chicago, Illinois.

- E. W. Chambers, 17 Craighead Road, Pittsburgh.

- M. P. Mahan, Department of Internal Revenue, 1788 Lanier Place, Washington, D. C.

- A. Nook, Department of Internal Revenue, 1788 Lanier Place, Washington, D. C.

Members of the crew were:

- Capt. Lowell Scroggins, pilot, Washington, D. C.

- J.P. Moore, co-pilot, Washington, D. C.

- Margaret Carson, hostess, Pittsburgh.

- Donald Staire, PCA observer, Washington, D. C.

Townsend Rally Speaker

Minneapolis, Minn., Aug. 31 (UP) –

Sen. Ernest Lundeen (FLR-MN), one of 25 killed in the PCA plane crash near Lovettsville, Va., today, was scheduled to speak at an all-state picnic of Townsend clubs at an amusement park near here Sunday.

The Pittsburgh Press (September 1, 1940)

Crash Sounded Like Lightning

By Mrs. Viola Thompson (As Told to the United Press)

…

Lovettsville, Va., Aug. 31 –

I was upstairs in my room when I heard the noise of a plane going over. Ordinarily, I don’t pay much attention to them, because they are going over all the time.

This one, though, struck me funny. The noise seemed much too low and much too loud. As it got louder, I ran to the window and looked out.

It was blinding rain, so I couldn’t see much. Suddenly, right over there in the field, was a blinding flash. I can’t describe it any better than to say it was like 10 sheets of lightning rolled into one.

The next moment was a terrific explosion that nearly deafened me. For one moment, the thought “bomb” came into my mind. Then I knew it must have been the plane that had crashed.

There was only one explosion. I don’t know what could have happened. The engine had sounded all right, not backfiring or missing or anything – just loud.

I don’t know what I did then. I guess I just sat there and screamed and screamed and screamed.

TEXT OF P.C.A. OFFICIALS’ STATEMENT ON CRASH

At midnight Saturday, Pennsylvania Central Airlines officials issued this formal statement on the crash of its luxury liner in the Virginia Mountains in which 25 persons lost their lives:

At approximately 3:50 (EDT) this afternoon, one of our planes flying on schedule between Washington and Pittsburgh made contact with the ground with terrific force four miles north of Hillsboro, Va., resulting in instantaneous death of 25 persons including 21 passengers, two pilots, an air hostess and one other company employee.

The probable cause of the accident has not yet been determined. Officials of the company are now at the scene directing relief activities and co-operating with officials of the Civil Aeronautics Board to determine the cause.

Electrical storms were present in the area at the time of the accident.

Captain Scroggins, the pilot, was proceeding on a regular course at the time of impact and was approximately 42 miles northwest of Washington. Wreckage being recovered over an area of two acres is being carefully studied tonight. All remains are being removed to Leesburg, Va. The plane was demolished.

AIR BOARD TRANSFER BLAMED FOR CRASH

Washington, Aug. 31 (UP) –

Senator Pat McCarran (D-NV) tonight blamed the airplane accident in which Senator Ernest Lundeen (FLR-MN) and 24 others were killed on the “chaos and confusion existing in the Civil Aeronautics Board.”

Mr. McCarran declared that “this awful condition” has existed since President Roosevelt transferred the agency this spring from its independent status and placed it in the Commerce Department. The Nevada Senator led an unsuccessful fight in the Senate against the approval of the President’s reorganization order.

Mr. McCarran declared that:

There will be other and more disastrous wrecks unless the CAB is again put back in its independent status so that efficiency may prevail.

AIRLINES’ SAFETY RECORD STRESSED

Chicago, Aug. 31 (UP) –

Colonel Edgar S. Gorrell, president of the Air Transport Association of America, tonight issued the following statement regarding the crash of the Pennsylvania Central Airlines plane at Lovettsville, Va., today:

Up until five days ago, airlines of the United States flew 1,300,000,000 passenger miles without a fatality or injury to any persons. In this period, the airlines carried 3,100,000 passengers.

LUNDEEN KNOWN AS ISOLATIONIST

…

Peace Advocate Voted Against Conscription Bill

…

Washington, Aug. 31 –

Tall, broad shouldered and bald Senator Ernest Lundeen of Minnesota, killed in a Pennsylvania Central Airliner crash today, was one of the foremost isolationists and ardent peace advocates through long service in the House of Representatives and in the Senate.

Only a few days ago, he was among the Senatorial minority which voted against approval of the Burke-Wadsworth bill to conscript American youth for peacetime military training.

Mr. Lundeen urged the settlement of the British World War debt through the taking over by this country of British possessions in the West Indies.

Seizure Urged

Soon after he came to the Senate in 1936, he began advocating seizure of Bermuda and other British territory as a means of settling the debt.

Senate colleagues listened politely but smiled inwardly at the suggestion. But they changed their attitude when President Roosevelt recently entered into negotiations to lease British bases in the Western Hemisphere as ports for the United States Navy and Air Corps. Mr. Lundeen contended that he was responsible for the program.

In 1918, a Minnesota crowd ran Mr. Lundeen out of town because, as a Congressman, he had voted against United States’ entry in the World War. In 1936, Minnesotans elected Mr. Lundeen to the Senate on the Farmer-Labor ticket.

Because he voted to keep his country out of the war, he lost his seat in Congress in 1918. Although he felt himself partially vindicated by being invited by the G.A.R. to deliver the Memorial Day address at Arlington National Cemetery in 1919, he was unable to win his way back to Congress until 1932.

Then in 1936, a Democratic coalition with the Farmer-Labor Party swept him into the Senate. Curiously, Mr. Lundeen balked at a similar coalition in 1930 – that time he was asked to withdraw from the Senate race in favor of a Democrat, but he refused.

Although beneficiary of Democratic support in 1936, Mr. Lundeen accepted the policies of the Roosevelt Administration with reservations. He urged his own social security program in which unemployment compensation would be paid entirely by the Federal Government.

Mr. Lundeen was born in Beresford, South Dakota, Aug. 4, 1878, the son of a Swedish-born missionary preacher and farmer. He graduated from Carleton College, Northfield, Minn., in 1907, and served two years on the law faculty of the University of Minnesota. He served from 1910 to 1914 in the Minnesota House of Representatives and from 1917 to 1919 in Congress.

Spanish War Veteran

From 1920 to 1932, fidelity to his liberal views helped bring defeat in races for Senator, Representative, Governor and Chief Justice of the Minnesota Supreme Court. At one time, he edited and published a monthly magazine called Uncle Sam.

Mr. Lundeen saw service in the Spanish-American War, was commissioned in the Minnesota National Guard and fought for the soldiers bonus. But he was a foe of war. In 1935, he urged slashing naval appropriations in half.

All we need is to defend our own soil.

He was of sturdy build and had blue eyes. In public speech, his delivery was choppy. His passions were peace and social security. His chief delights – conversation and the outdoors.