The Pittsburgh Press (April 19, 1945)

Writer to be buried in Army cemetery

By Mac R. Johnson, United Press staff writer

From the last two paragraphs of Here Is Your War, by Ernie Pyle, written after the African campaign.

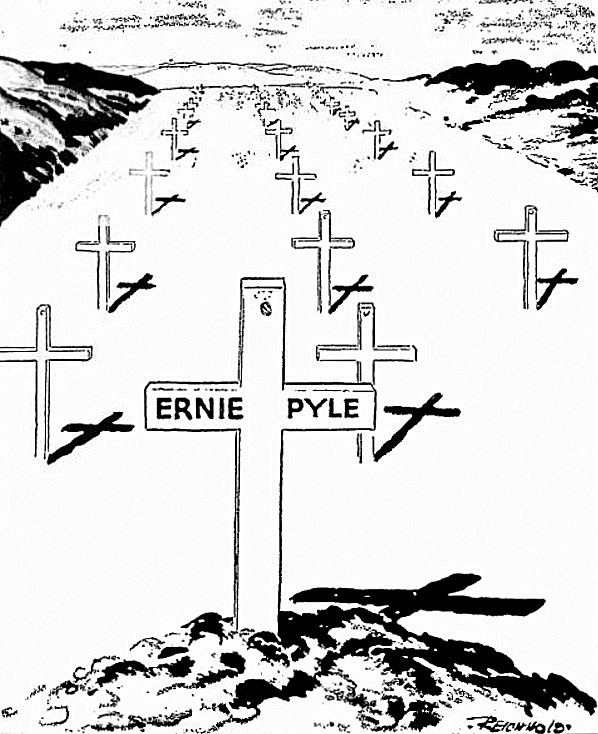

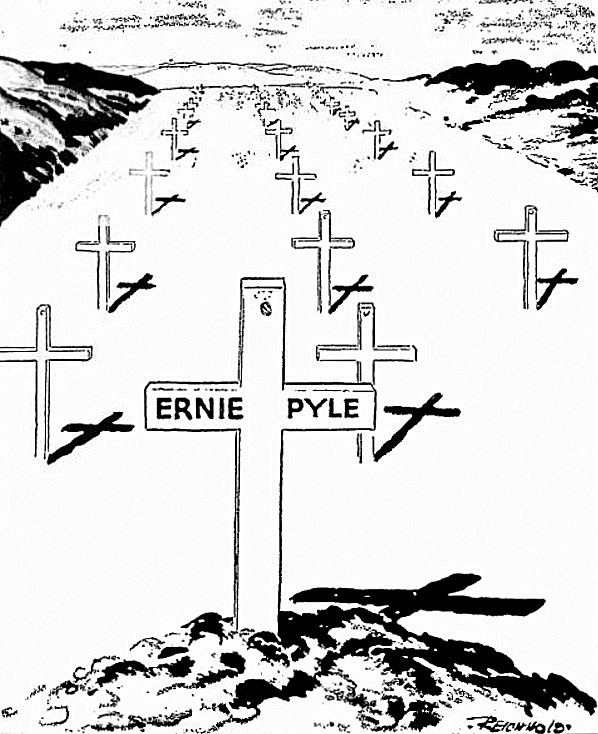

On the day of final peace, the last stroke of what we call the “Big Picture” will be drawn. I haven’t written anything about the “Big Picture,” because I don’t know anything about it. I only know what we see from our worm’s-eye view, and our segment of the picture consists only of tired and dirty soldiers who are alive and don’t want to die; of Jong darkened convoys in the middle of the night; of shocked silent men wandering back down the hill from battle; of chow lines and atabrine tablets and foxholes and burning tanks… and the rustle of high-flown shells; of jeeps and petrol dumps and smelly bedding rolls and C rations and cactus patches and blown ridges and dead mules and hospital tents and shirt collars greasy-black from months of wearing; and of laughter, too, and anger and wine and lovely flowers and constant cussing. All these it is composed of; and of graves and graves and graves.

That is our war, and we will carry it with us as we go on from one battleground to another until it is all over, leaving some of us behind on every beach, in every field… I don’t know whether it was their good fortune or their misfortune to get out of it so early in the game. I guess it doesn’t make any difference, once a man has gone. Medals and speeches and victories are nothing to them anymore. They died and others lived and nobody knows why it is so. They died and thereby the rest of us can go on and on. When we leave here for the next shore, there is nothing we can do for the ones beneath the wooden crosses, except perhaps to pause and murmur, “Thanks, pal.”

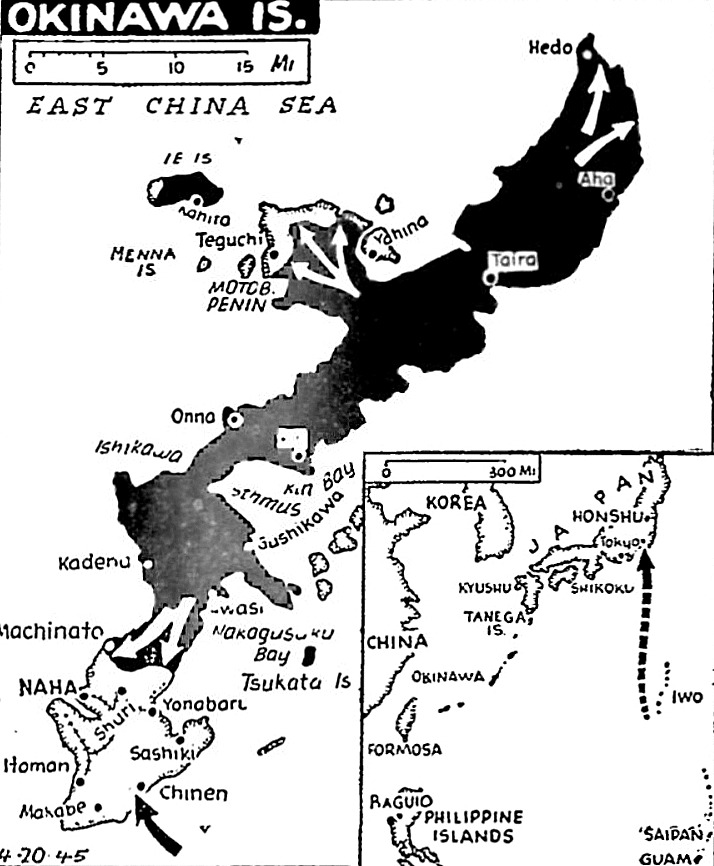

OKINAWA – Ernie Pyle will be buried among the soldiers he immortalized.

The beloved little war correspondent killed by a Jap machine-gunner yesterday probably will be laid to rest in an Army cemetery here in the Ryukyus where he covered his last campaign.

The soldiers he loved brought him back from the battlefield back to where the noise of the guns is distant and dull. They lifted his pint-sized frame from the ditch where he fell, victim of a sneak machine-gun ambush.

They put him on a litter, and crossed his arms, and then carried him back to the rear.

Jap jealous of prize

It wasn’t easy. That Jap machine-gunner seemed jealous of his prized victim. It was four hours after Ernie was killed before anybody could get to his body.

Cpl. Alexander Roberts, Army photographer from New York City, tried to get in to take pictures. He said every time anybody would try to enter the clearing where Ernie had been killed the gunner would open up.

Finally, Cpl. Roberts crawled into the clearing on his belly, pushing his camera ahead of him.

“Ernie’s face was not twisted in pain or agony,” he said. “He looked pleasant and peaceful. If there hadn’t been a thin line of blood at the corner of his mouth, you might have thought he was sleeping.”

Said he would get it

Ernie always said he would get it, that he had used up his chances. He said it again just before he landed with the assault troops on Okinawa. He told a public relations officer that he had a premonition about the campaign. And he said to another officer that he thought he would go back to the States “right after this one.”

Instead, he went from Okinawa to Ie Island because, as he told a friend, his premonition was “pretty silly as I’ve run into nothing hot yet.”

So he went on

So he went on – as he had gone from Ireland to North Africa, to Sicily, Italy, France and the Pacific – to get more stories about his beloved G.I.’s. He wanted to write about the Marines.

Erie was an old dough from the word go. He sweated and suffered with the doughfeet, shared their hopes, fears, and thrills – their lives. Today he shared death with them and it was believed he would be put to rest with them, in a G.I. Army cemetery.

Ernie would have liked that.

Ernie Pyle spent his last hours doing the job he had always done – gathering notes from G.I.’s for his columns, James MacLean, United Press correspondent, reported.

Detained by cold

A two-day-old cold had confined him to the sick bay of a transport and prevented him from landing with other correspondents in the assault waves on Ie until Tuesday. He spent that day interviewing soldiers and officers on the battlefield.

Wherever he went he was surrounded by G.I.’s who swarmed around him, forgetting the battle in progress. They tried to get him to autograph captured Jap money, American bills or invasion bills until their officers ordered the men back into position.

Milton Chase, 33, a correspondent for Radio Station WLW in Cincinnati, and a former staff member for United Press in Shanghai, said Ernie walked very carefully on Ie, because of his fear of landmines.

Mr. Chase said:

He told me that the weapon he hated worst – more than machine guns, shells or anything else – was “stumbling blindly into minefields because they explode before you can duck or take cover.”