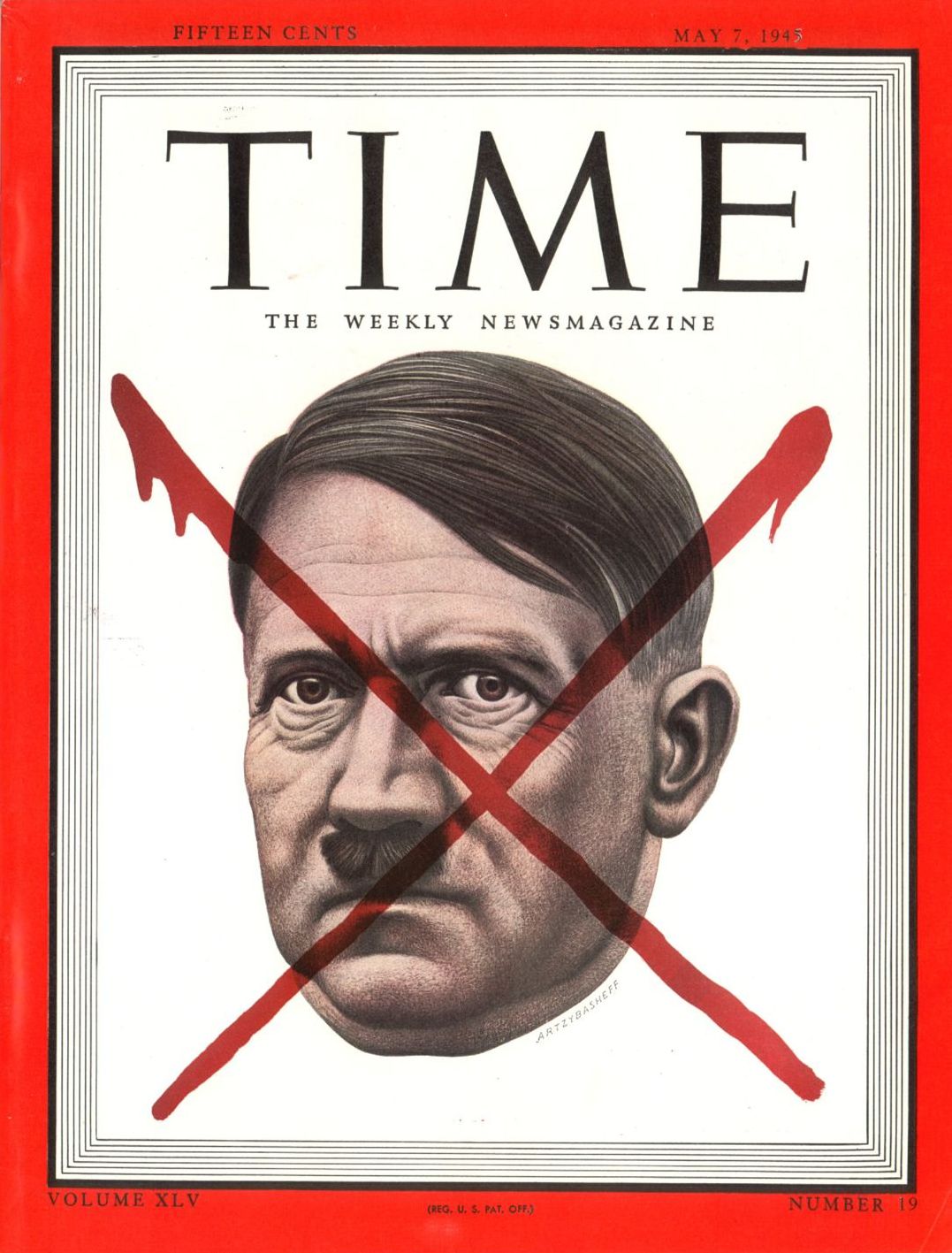

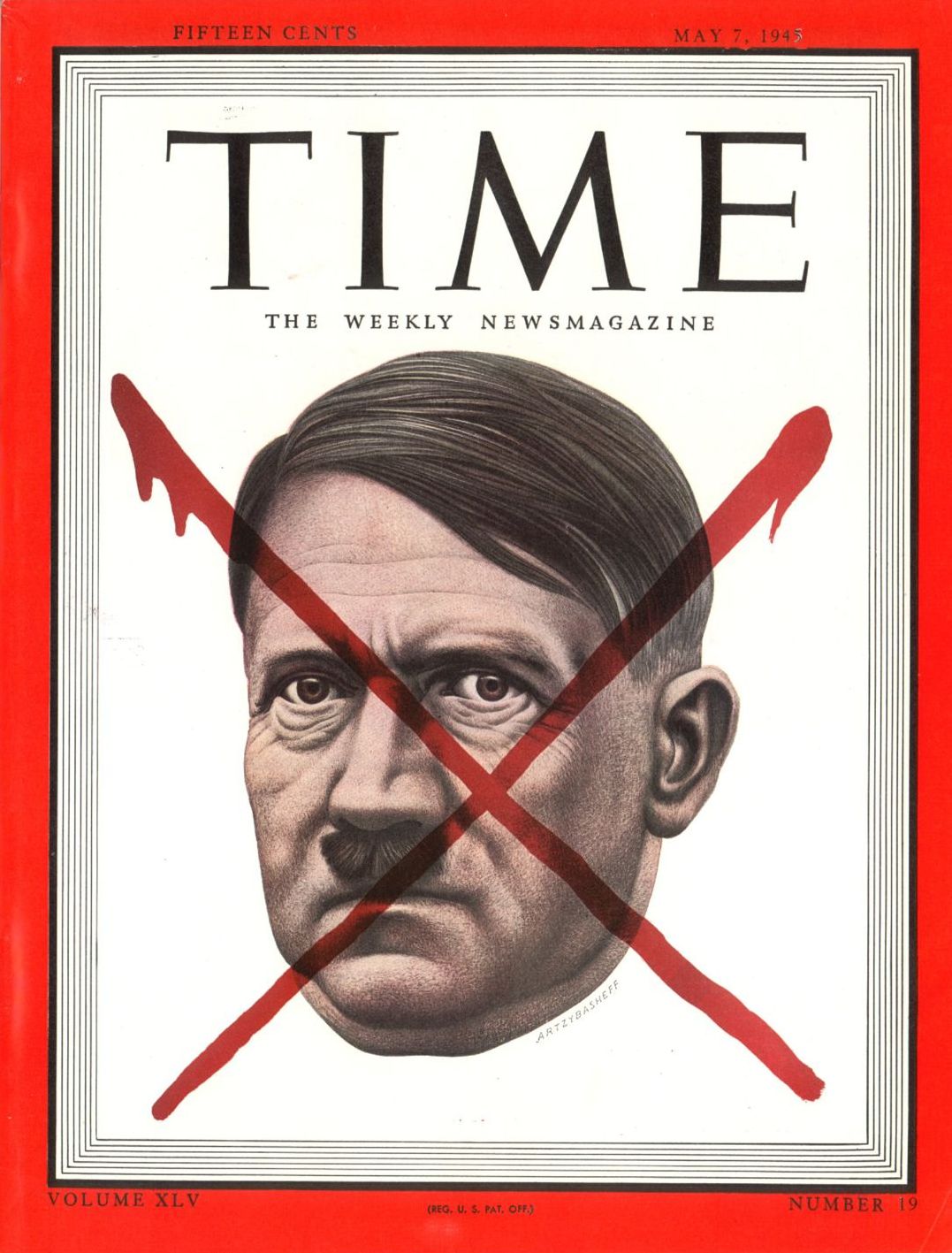

GERMANY: The Betrayer

Monday, May 07, 1945

THE VOICE OF DESTRUCTION: ‘You may have begun man, but I, Adolf Hitler, will finish him.’

Fate knocked at the door last week for Europe’s two fascist dictators. Mussolini, shot in the back and through the head by his partisan executioners, lay dead in Milan. Adolf Hitler had been buried, dead or alive, in the rubble of his collapsing Third Reich. Whether or not he had suffered a cerebral hemorrhage (as reported from Stockholm), or had “fallen in his command post at the Reich chancellery” (as reported by the Hamburg radio, which said that he had been succeeded as Führer by Grand Admiral Karl Doenitz), or was a prisoner of Gestapo Chief Heinrich Himmler, Adolf Hitler as a political force had been expunged. If he were indeed dead, the hope of most of mankind had been realized. For seldom had so many millions of people hoped so implacably for the death of one man.

If they had been as malign as he in their vengefulness, they might better have hoped that he would live on yet a little while. For no death they could devise for him could be as cruel as must have been Hitler’s eleventh-hour thoughts on the completeness of his failure. His total war against non-German mankind was ending in total defeat. Around him, the Third Reich, which was to last 1,000 years, sank to embers as the flames fused over its gutted cities. The historic crash of what had been Europe’s most formidable state was audible in the shrieks of dying men and the point-blank artillery fire against its buckling buildings.

All that was certain to remain after 1,000 years was the all but incredible story of the demonic little man who rose through the grating of a gutter to make himself absolute master of-most of Europe and to change the history of the world more decisively than any other 20th-century man but Lenin. Seldom in human history, never in modern times, had a man so insignificantly monstrous become the absolute head of a great nation. It was impossible to dismiss him as a mountebank, a paper hanger. The suffering and desolation that he wrought was beyond human power or fortitude to compute. The bodies of his victims were heaped across Europe from Stalingrad to London. The ruin in terms of human lives was forever incalculable. It had required a coalition of the whole world to destroy the power his political inspiration had contrived. How had it happened? If it was necessary to exterminate Hitler and his works, it was equally necessary to try to understand him.

Clearly so absurd a character, so warped and inadequate a mind, despite its coldblooded political discernment, could not in so short a time have worked such universal havoc if it had not embodied forces of evil in the world far greater than itself.

Everything – backward environment, shabby heredity, dingy ambitions, neurotic sensitivity – prepared Hitler for his future role. But the beginnings of the future scourge of mankind were bucolic, even idyllic. Hitler was born (1889) at Braunau in Austria-Hungary, among the blue foothills of the Tirolean redoubt.

From his mother, the 20-year-old third wife of his 53-year-old father, Hitler inherited his psychotic blue-green eyes, and probably his tendency to tantrums and his anemic artistic talent. From his father, who had risen by a lifetime’s effort from a peasant to a petty customs inspector, Hitler probably inherited a toughness of character that was not so much strength as a persistent stubbornness in overcoming weakness.

He was a somewhat strident boy, who early tried out the Führerprinzip (leader principle) by bossing his schoolmates (“I became a little ringleader at that time”). One day he discovered an account of the Franco-Prussian War in two old popular magazines. “Before long that great heroic campaign had become my greatest spiritual experience.”

The Führerprinzip had no effect on Hitler’s father, who wanted his son to become a petty official. Hitler wanted to become an artist. The long struggle between them was ended only by the death of his father. Then his mother sent him to art school. Two years later she died. Young Hitler packed his few clothes in a suitcase and struck out for Vienna.

It was a momentous trip for mankind. For in gay, cosmopolitan, highly civilized Vienna the young German nationalist from the Alps suffered for the first time three new urban experiences that profoundly influenced his future: the slum proletariat, Social Democratic trade unions, Jews.

His political education kept pace with his human observations. Hitler learned to know trade unions when he got a job as a bricklayer. “When I was told I had to join, I refused." The radical talk of his fellow workers disgusted him.

Adolf tried to reason with his fellow bricklayers. “I argued till finally one day they applied the one means that wins the easiest victory over reason: terror and force." He was learning fast. Hitler was given the choice of quitting the job or being tossed off the scaffold. He quit. He also took to reading Socialist literature and attending Socialist meetings to find out what it was all about. His researches led him to a conclusion that was to blossom later into the horrors of concentration camps like Maidanek, Buchenwald and Dachau.

Soon Hitler was reaching equally luminous conclusions about the Jews. He began to read the publications of Vienna’s violently anti-Semitic Mayor Doktor Karl Lueger and his Christian Socialist Party. “One day when I was walking through the inner city, I suddenly came upon a being clad in a long caftan, with black curls. Is this also a Jew? was my first thought… But the longer I stared at this strange face and scrutinized one feature after the other, the more my mind reshaped the first question into another form: Is this also a German?"

Soon young Hitler’s researches had revealed to him that the Jew is the enemy of all mankind, but by special malice, the peculiar enemy of the Germans.

In 1912 Hitler moved from racially impure Vienna to Munich. There he continued to live a slum existence, eking out a bare living by peddling his watercolor paintings. There in June 1914, the news reached him that a Serbian nationalist had shot and killed the Archduke Franz Ferdinand at Sarajevo.

When Germany declared war and even the Social Democrats voted the war credits, Hitler was transported. Since he was an Austrian, he asked for and received permission to join a Bavarian regiment. The war was wonderful. The army was more wonderful. Hitler was made a corporal, received an Iron Cross, was wounded, and later gassed. While he was recuperating in a hospital near Berlin, news came of the German Revolution of 1918, and of the Armistice that was to save Germany from Allied invasion. Hitler buried his face in his pillow and wept. Then he decided to give up art and architecture for a new profession: “I, however, resolved now to become a politician.”

One more step was necessary: the newly minted politician must find a political party. Hitler found it in the German Workers’ Party, a tiny group which the Bavarian Reichswehr officers had sent him to observe. He became member No. 7 of the little party which was later to become the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Nazis). He found an impressionistic economic program in the scrambled economic theories of another member, Gottfried Feder. And he found something much more important – his voice. One night a visitor said some friendly words about Jews. Without thinking twice, Hitler burst forth in speech. He had become an orator.

Then Hitler made one of the most valuable mistakes of his life: he and his handful of Party comrades decided to seize the Bavarian Government. Hitler had promised to kill himself if the attempt failed. Instead he went to jail in the Landsberg prison in a cozy cell (compliments of friendly officials).

In Landsberg, with the help of Rudolf Hess, he wrote Mein Kampf (My Struggle). Seldom has a plotter set forth his purposes in plainer language or more explicit detail. The book was badly organized, but in it were the plans for Hitler’s aggression against Germany and the rest of the world. The intellectuals contented themselves with laughing at Hitler’s ideas and correcting his literary style.

Hitler had been sentenced to jail for five years. He was out in nine months.

His prestige had increased. One by one the perverse paladins of the Nazi inner circle gathered around him:

-

Hermann Goring, the former flyer and drug addict.

-

Dr. Paul Joseph Goebbels, the unsuccessful novelist who became the Nazi Party’s satirically clever propagandist.

-

Joachim von Ribbentrop, the champagne salesman who became No. 1 Nazi diplomat.

-

Julius Streicher, the obscene and sadistic Jew-baiter who became Gauleiter of Franconia.

-

Captain Ernst Rohm, the homosexual organizer of the Brown Shirts, who was shot in the Blood Purge.

Slowly the Party extended its connections among financiers, industrialists and Government men. For Hitler had learned one lesson from the Beer Hall Putsch: legal, not violent, revolution was the strategy for Germany.

The education of Adolf Hitler was all but completed. The terrible education of the world was about to begin.

It began with Germany. To Germany Hitler and his Party offered to sell protection against Marxism.

It was a purpose that most non-Communist Germans could understand. For in the election that was to carry the Nazis to power the German Communist Party polled 5,970,833 votes. The Nazis fought Communism with the weapons of Communism. To oppose the Communist troops (Red Front Fighters), the Nazis used the Brown Shirts. In place of the dictatorship of the proletariat, the Nazis offered the dictatorship of the Nazi Party. In place of Bolshevism’s scapegoat, the bourgeois, the Nazis offered the Jew. In place of internationalism, the Nazis offered fanatical German nationalism. In place of one dominating class (the proletariat), the Nazis offered the people (Volk).

In place of unemployment, the Nazis offered an economy geared to war production, with jobs for all. In foreign affairs the Nazis clamored for a revision of the Versailles Treaty.

The scheme worked. How well, time quickly told:

-

In 1928 the Nazis won twelve Reich stag seats; in 1930 they won 107; in 1932, 230.

-

In January 1933, senescent President Paul von Hindenburg appointed Hitler Chancellor.

-

In June 1934, Hitler carried through the Blood Purge and became absolute Führer of the Nazi Party. In August Hitler became absolute head of the German state.

-

In 1935 the Saar returned to Germany.

-

In 1936 Germany reoccupied the Rhineland and signed the anti-Comintern pact with Japan.

The same strategy that had succeeded in Germany was transferred to foreign affairs; only, this time the Nazis sold protection against Russia.

In March 1938 Hitler seized Austria.

In September, he enticed Britain’s aging, fatuous Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain to Munich. There the Sudetenland was ceded to Germany as the price of “peace in our time."

In March 1939, Hitler occupied the rest of Czechoslovakia. A few days later, he took Memel from Lithuania. In April he made territorial demands on Poland. Britain threatened war. On August 23, Germany and Russia agreed to sign a non-aggression pact. A week after it was initialed, the Wehrmacht overran Poland. World War II had begun.

Last week, with their country four-fifths conquered by the Allies, Nazi fanatics were still forcing the Germans to fight on. There was little left to fight for or with.

From Germany TIME Correspondent Percival Knauth cabled:

If Hitler is today lying dead on a street in Berlin, like Benito Mussolini on a sidewalk in Milan, there will be few people in Germany who will be mourning his passing. The few will be the Nazi Party’s fanatic core who still believe in Nazism, and for that belief and for the sake of their own lives fight on. A growing majority of Germans, however, are looking on Adolf Hitler today with bitterness and angry despair as the man who gambled them and their lives away.

This realization is dawning on Germans as they come out of the trance-like state in which they fought the war until the Allied armies crossed the Rhine. It is not the realization of their own measure of responsibility for what has happened to them; if that comes to them it might be their salvation. It is an awakening which is expressing itself in the old cry heard after the last world war: “Wir sind belogen und betrogen warden” – “We have been lied to and betrayed.”

I heard that cry in Leipzig last week expressed in just those words. The janitor of an apartment house which stood alone in a street of utter wreckage buttonholed me, shook his fist in my face and cried: “You must tell your people how we’ve been lied to and betrayed! Every day we see it more and more! Every day we have more and more proof of how those men have ruined us! And they’re still fighting, letting us be killed – they’d drag our whole country down to death with them if they could!"

And someone else in Leipzig said to me, a young girl whom I had known before the war who has a two-and-a-half-year-old son now and a husband somewhere down in Austria: they gambled everything away, everything. We are lost as a nation. If I had known when I was in school that this was going to happen, I would have committed suicide.

It is the same picture in all parts of occupied Germany which I have seen and where I have talked to Germany’s little people. When the Nazis left their towns and villages a world came to an end for them. Leaderless, helpless, they watched the Americans come in. As a mass they did not know what to do. Without newspapers, without radio, without all the thousand and one accustomed details with which the Nazis had organized their daily lives and influenced their daily thought, they slowly began to realize the full scope of the catastrophe which had befallen them, how thoroughly they had been cut off from and ostracized by the outside world which was now bursting in upon them with such cataclysmic power.

It is what they have lost that is haunting the Germans now. As long as the Nazis were still there, exhorting them, promising them victory and restoration, most of them did not fully realize how complete their loss actually was. It is a material loss measurable in homes destroyed, industries bombed into ruins, fortunes burned up in incendiary bombs. It is a moral loss felt in the loss of national honor, independence and dignity. It is the loss of every foundation of their lives, and many Germans already and probably many more to come see only one way out: suicide.

In that respect it seems that even the war has not changed the German character. It has not infused new political strength into these people who can not only be led, hypnotized, to their own destruction, but can actually be made to participate in it. In all the various emotions which the Germans are feeling now – fear, anger, hopelessness, bitterness, shame, servility and helplessness – there is one which you will rarely find and that is a sense of guilt, the sense of being responsible personally and as a nation for what has happened.

Most Germans realize now or profess to realize that this war was unnecessary and wrong. But they still don’t go beyond that to the salient realization that Nazism and everything that went with it was wrong. The main reason the war seems wrong to them is because they lost it. They place the blame on Hitler because he got them into it; if he had won the war few people in Germany today would be concerned with the question of whether the war was right or wrong.

Judging by present appearances, it does not seem likely that Adolf Hitler will go down in German history as a martyred leader. All last week the radio was propagandizing him as the nation’s military and spiritual leader fighting at the head of his troops in Berlin. Nobody I met was in any way impressed. But when rumors circulated that the Führer had been killed in Berlin, Germans began to stop Allied soldiers on the streets to ask them if it was true. What they were concerned about, however, was not whether Hitler was alive or dead. What they said was: “If it is true, then finally perhaps the war will end.”

For the German people, as for the rest of the world, the end of World War II would bring – had already brought – one tremendous, if negative, good: the end of the monstrous historical lie embodied in Nazism and its perverted practices. Hitler, if he were still able to wonder what his historical function had been as everything crumbled, might say with Mephistopheles in Goethe’s Faust: I am

Ein Teil von jener Kraft,

Die stets das Böse will

und stets das Gute schafft.

(Part of that force,

That is forever willing evil,

continually produces good.)