The Pittsburgh Press (April 28, 1945)

Rebellion in Munich

Two U.S. armies near Bavarian city as rebels ask help

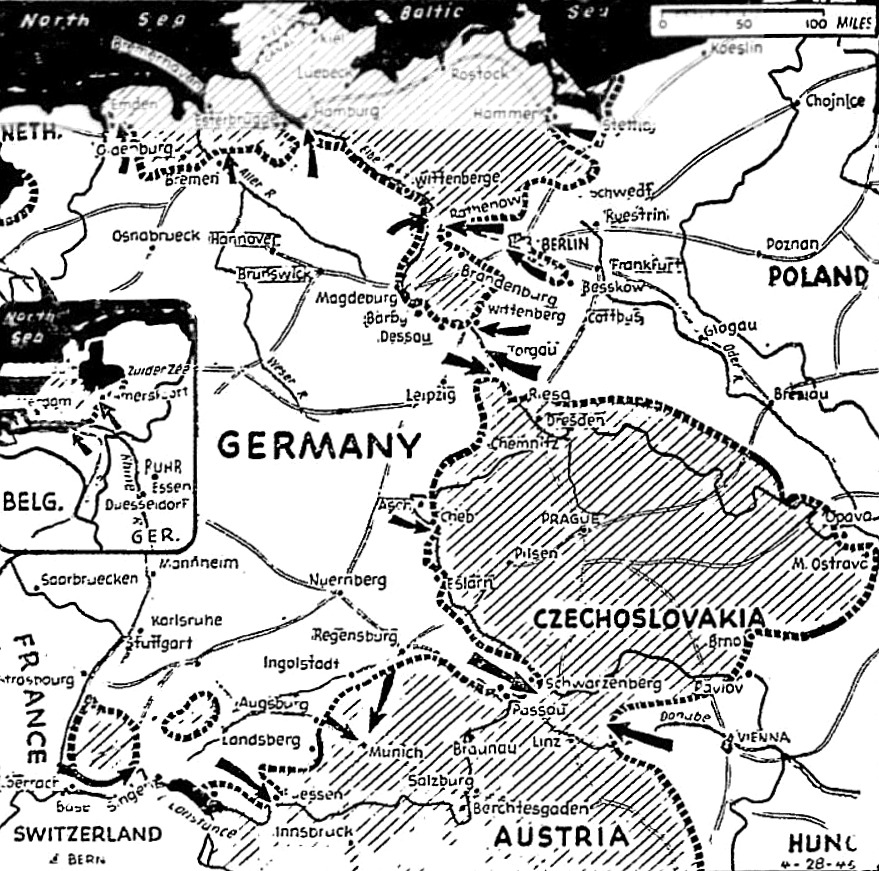

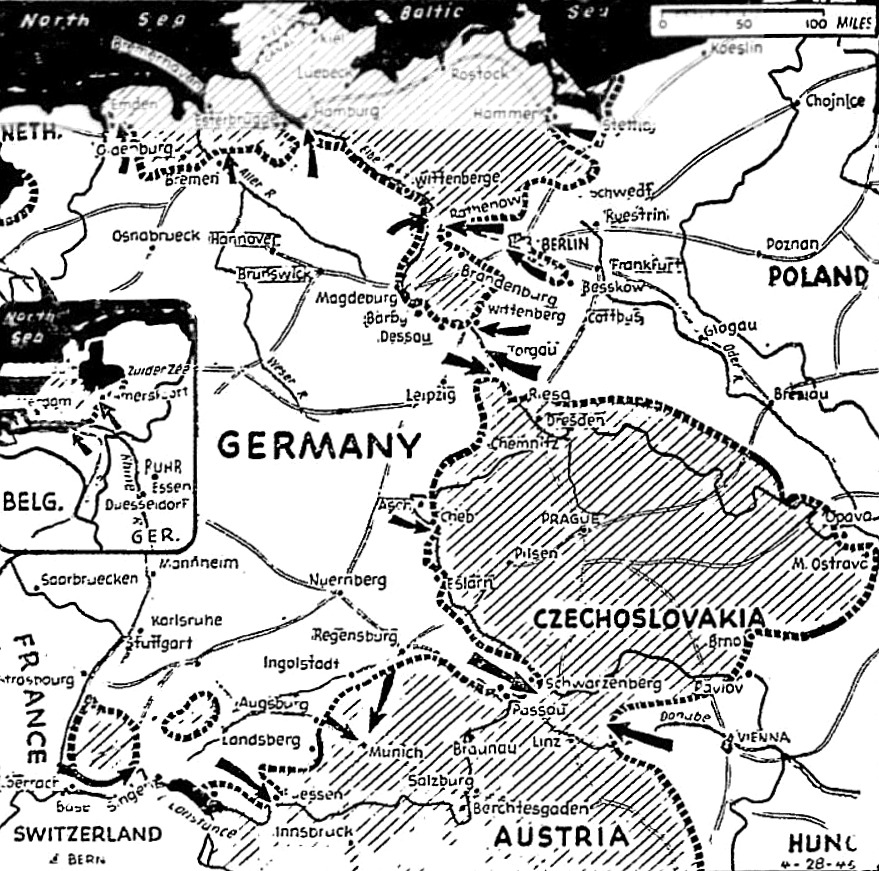

Slashing ahead in the south, the U.S. Third and Seventh Armies were running riot over the defenses of the Nazi redoubt. An anti-Nazi revolution was raging in Munich. The Seventh Army reached the Austrian border at Fuessen. The Third Army, across the border to the east, was driving for a junction with the Second Ukrainian Army west of Vienna. To the north, the First Ukrainian Army reached the Elbe River and another junction with the U.S. First Army at Wittenberg.

PARIS, France (UP) – Revolutionists seized control in Munich today and radioed an urgent appeal for American help in overthrowing the Nazis.

At midday, however, a broadcast purporting to come from the Nazi gauleiter in the city claimed the uprising had been suppressed.

From confused radio broadcasts and censored front dispatches, one clear fact emerged – the fires of revolution had been lighted in Bavaria, once the strongest citadel of Nazidom.

And two U.S. armies were racing in on Munich from positions less than 30 miles to the west and north in answer to a desperate appeal from the rebels for immediate help.

The Nazi gauleiter called on Bavaria to continue what obviously was a hopeless fight against the converging American armies and declared that the Munich “traitors” had been dealt with ruthlessly.

There was no confirmation of the Nazi claim which in itself was the first enemy admission that the dreaded peace revolution had begun, just as it did in 1918 in the final hours of World War I.

‘Hour of freedom has struck’

Field dispatches from the Third Army front identified the rebel leader as Gen. Franz Ritter von Epp, last reported as a member of the Hitler government and one of the first Nazis elected to the Reichstag.

A rebel broadcast to the people of Munich and apparently also to French slave workers in Bavaria quoted von Epp as announcing that Germany’s capitulation was “imminent” and that “the hour of freedom has struck.”

Von Epp, or a spokesman, declared that he had decided to break off the fighting against the Americans.

He said:

In this hour, there is but one thing that matters, namely calmly and with faith in the new leadership to see to it that the bloodshed be discontinued and that the calamity which has befallen the German people be not aggravated by a fight between Germans and Germans.

Preserve calm and order, thereby making it possible for the new leaders to restore normal life as quickly as possible.

Later, a speaker claiming to be Paul Giesler, Nazi gauleiter of Munich and Upper Bavaria, broadcast over the same wavelength a claim that the Nazis had regained control of the situation.

He admitted that some of the rebels still were at large, although he contended the uprising was staged by a “handful” of traitors led by an obscure German Army captain.

Appeals to Bavarians to back Nazis

Without naming von Epp, the Nazi spokesman charged the rebels with the false use of high Nazi names as a “front” for their movement.

He said in an appeal to the people of Bavaria to stand by the Nazi regime:

By mentioning the names of high officers, this captain, who speaks over a treasonable transmitter, is deceiving the population.

Apart from his small band, a mere handful of men, nobody has the slightest intention of making an end of the struggle in this fight for our homeland.

Do not let yourselves be turned in treason. Nobody will follow a man who sells Germany. He will not escape his punishment… Wherever individual traitors appear they must be dealt with on the spot.”

Von Epp appealed to the Americans to bomb Field Marshal Albert Kesselring’s headquarters at Pullach, six miles south of Munich.

United Press writer Robert Richards reported from the Third Army Front that the spokesman announced formation of a “Free Action of Bavaria” group and warned that any Germans remaining loyal to the Nazis would be treated as war criminals.

Confirmation of the Munich revolution came on the Swiss border from a high diplomat who arrived in Switzerland with a story of disorder and anti-Nazi violence throughout the Reich.

The diplomat said Hitler and Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels had been shot three days ago.

Regensburg and Augsburg, twin outer citadels of Munich 60 and 30 miles to the north and northwest, were in American hands and German troops were surrendering by the thousands all around the city’s approaches.

At the same time, U.S. Seventh Army troops raced down to the Austrian border at Fuessen, 55 miles southwest of Munich, in an apparent bid to envelop the former Nazi citadel and choke off any possible reinforcement through the Brenner Pass from Italy.

At Fuessen, the Yanks were only 38 miles from Innsbruck, northern gate to the Brenner Pass.

Gen. George S. Patton’s U.S. Third Army was closing on Munich from the north after capturing Regensburg, and his armored task forces were plunging into Austria 60-odd miles farther east in a drive that threatened to envelop Hitler’s Alpine hideout at Berchtesgaden.

Gen. Patton’s troops were in direct radio contact with Russian troops in Austria and field dispatches said the two armies were on the verge of linking up for a joint assault on Berchtesgaden.

Coming on the heels of the American-Russian juncture in the north that cut Germany in two and split the enemy’s surviving divisions into isolated islands of resistance, the American hammer blows in the south plainly were beating Hitler’s Reich to its knees.

55,000 surrender

On the northern and western roads to Munich, the U.S. Third and Seventh Armies were running roughshod over the wreckage of what had been the mightiest military machine m history.

An estimated 55,000 crack Nazi troops surrendered to the Americans in the area yesterday: 32,000 taken by Gen. Patton’s troops and 23,000 by Lt. Gen. Alexander M. Patch’s Seventh Army.

The survivors of the Bavarian host that Hitler had gathered to hold the ramparts of his southern redoubt were scattering in wild confusion through the mountain passes south and southeast of Munich.

Capture Landsberg

Units of Gen. Patch’s 10th Armored Division struck down to Fuessen and the Austrian border and sent a strong column to take Landsberg, midway between Augsburg and Fuessen and 28 miles due west of Munich.

Gen. Patton’s troops on the Seventh Army’s left flank were spilling across the Danube on a broad front east and west of Regensburg.

With that city firmly in their hands, the Third Army troops raced more than 10 miles southward in a half-dozen columns last night to reach positions less than 40 miles from Munich.

All organized resistance appeared to have broken in their path and it seemed likely that they would be at the gates of Munich with the Seventh Army in a matter of hours.

German resistance was also beginning to fall apart in the northwestern coastal pocket, where British Second Army troops cleared the last diehard Nazi fanatics from the wrecked docks of Bremen.

Other British troops and units of the Canadian First Army converged on the Wilhelmshaven-Emden coastal area with increasing speed, and front dispatches said the remaining Germans there were believed fleeing by sea to Norway and Denmark.