‘BIG ARMY’ MEETING TESTS OF INVASION

U.S. replacement plan seen proved at Cherbourg for blows that are coming

Loss of men held down; timing of Russian offensive a cheering factor – Goebbels’ tactics again warned of

By Sidney Shalett

Washington – (June 27)

Allied strategy in pressing the invasion of Europe consistently will follow a pattern of striking sharp, overwhelming blows in which we will expect and accept considerable losses, but avoiding, insofar as possible, any costly stalemates in which huge forces are locked with the enemy while the attrition mounts up on both sides.

It is possible today, on the basis of the latest military information received here from the battlefronts, to make the above statement authoritatively and also to evaluate some of the significant developments on the European fronts.

Allied strategists are aiming at a knockout as speedily and as economically as possible. They have no delusions that it will be a quick or easy job to defeat the Germans in the west, but they do not want the task to cost more lives or time than necessary.

Therefore, they are determined to employ the principle of genuine “lightning war,” combined with overwhelming force, against the Germans. The landings in Normandy, first of a series of expected blows, were an example of this. We landed quickly, with an element of surprise, and in sufficient force to achieve our objectives.

Our losses in France so far have been considerable, but still they have been a good deal less than the Allied High Command expected for the job.

System of rapid replacement

One of America’s “secret weapons” in both France and Italy – and this has been stressed by Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson – has been the extraordinarily effective system of immediate replacement of casualties and battle-weary troops. It worked well in Italy – Mr. Stimson gave it a great deal of credit for cracking German resistance south of Rome – and it is now working effectively against the Germans in France.

The theory is simple, but the accomplishment requires tremendous reserves and organization. What happens is this: Every 24 hours or as close to that schedule as practicable, U.S. casualties in combat division, and, to as great extent as possible, battle-fatigued troops, are replaced by fresh men.

Thus, the Germans, who have no such reserves in France, are constantly faced by an efficient, up-to-strength, offensive-minded force.

According to the best authoritative information here, the constant pressure is proving demoralizing to the Germans.

Another factor, involving the Germans’ attitude, is not helping the enemy. He knows that many of our divisions that are defeating him are in battle for the first time. Yet these “green” troops, because of the realistic and rigorous conditioning they have had, are outfighting Nazi veterans.

Germans are fighting well

Current advices indicate that the purely German units are fighting extremely stubbornly. Cherbourg proved that, although it demonstrated once again that the defeated “superman” can be consistently beaten by his betters. Where German units are mixed with foreign soldiers pressed into Nazi service, the results are not particularly happy for the foe.

So far as can be learned, the U.S. Army is in a position to carry on its replacement system throughout the Battle of Europe, provided that the flow of young, tough replacements – the under-26 group for which our military chiefs have pleaded – keeps coming into the Army. A table of expected losses has been worked out, and our chiefs think they can handle the replacement problem.

The success of the replacement system in Italy and France is viewed by some here as vindication of the “Big Army” pleas made by our chiefs at a time when there was considerable controversy over why we needed a force as large as they asked for.

The Germans have been far from infallible in divining either our potentialities or our intentions. They never dreamed we would be able to pout in so many men and so much matériel in so short a time on what they regarded as mere beaches in Normandy.

The fact that we did, is a tribute to the careful and skillful planning of our invasion leaders.

The Allied air situation over Europe at present is regarded as quite satisfactory. Our superiority over France seems to be operating as effectively as the superiority we have held in the skies over Italy. The question, “Where is the Luftwaffe?” is more than a sarcastic taunt at the moment. Our commanders really would like to throw what they can do to engage and smash the German fighter force.

There is satisfaction in official circles over the Russian military offensive. It is learned that plans were made some time ago as to what the Russians would do when we opened up in the west. The Russians have fulfilled their part of the plans.

Informed circles here predict that Reich Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels will make further frantic efforts to split the Allies before the tottering Nazi castle collapses.

They gravely and sincerely hope that no Americans will fall for this enemy line. Allied unity, it is stressed, is of utmost importance, both in Europe and in the Pacific.

Baldwin: No. 1 strategic triumph

Fall of Cherbourg judged beginning of the end for German war machine

By Hanson W. Baldwin

London, England – (June 27)

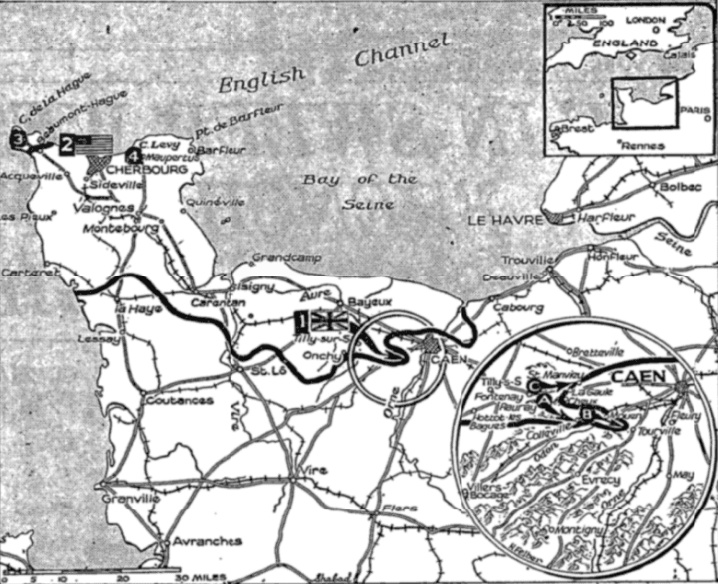

The capture of Cherbourg three weeks after the first landing in Normandy represents the greatest Allied strategic triumph of the war.

It may well be written by future historians as a decisive victory, for Cherbourg’s loss probably means the beginning of the end for the Germans. If anything can be forecast in war, it seems to mean – unless the enemy has “secret weapons” of undreamed-of potentialities – that the Germans have lost their last chance for victory or even for averting defeat.

This is not to say that the enemy has “thrown in the sponge” or that he is likely to do so soon. In one sense, the bitter, week-long defense of Cherbourg by second-rate troops and the hard, slow fighting in Normandy are disappointing. Tactically we can expect only more of the same; just as Cherbourg’s capture took somewhat longer than we had hoped and expected, so future battles in France are likely to be protracted and difficult.

Nevertheless, June 27 must go down as a red-letter day for the Allies, for Cherbourg’s fall means the bankruptcy of German strategy.

Single hope fading

For more than a year, German strategy has been plain. Adolf Hitler has made every possible effort to strengthen his forces in the west, some of his best generals and his best troops were assigned to France and the Low Countries; the German strength in these countries was increased from about 32 to more than 60 divisions, partly at the expense of other areas, since Stalingrad, Germany has been pinning her hopes for a limited victory upon one event and one alone: the repulse of the Allied invasion of the West.

Hitler hoped to make our repulse so bloody and so definite that he would win a great moral and psychological victory as well as a military one. His western flank thus freed of threat, he then undoubtedly planned to concentrate all his strength against Russia and force a negotiated peace.

There was never much doubt that when the Allies attempted the invasion of Western Europe, they could get ashore. But there was some doubt about our ability to hold a foothold; despite the German boasts about the impregnability of the Atlantic Wall, it is known that Field Marshal Gens. Gerd von Rundstedt and Erwin Rommel counted chiefly upon a counterattack to repulse the Allied invasion. Our quick penetration of the Atlantic Wall at considerably less cost than anticipated has now been followed by the capture of a port.

The German defense of the West has been based upon the defense of ports, for they knew, as we knew, that if the Allies were to retain their foothold in France, they had to have a port. If there was ever any doubt of this, the heavy storm of a week ago dispelled it.

Gale hampered unloading

It has now been revealed that a 75-mile gale from the northeast blew squarely on the invasion beaches in the Bay of the Seine and almost halted unloading for three and a half days. This gale was part of the freakish June weather – the most unusual in 25 years – which has hampered our unloading of supplies and reinforcements and air activities. So far most of the weather “breaks” have been against us.

It was for these reasons that the capture of Cherbourg this morning was hailed with relief by our supply experts. It is realized that German demolitions and the bombings and bombardments to which the port had to be subjected before German resistance was stamped out will probably delay full use of the port for some time.

But Cdre. William Sullivan, USN, the salvage expert who helped raise the Normandie and who was in charge of clearing North African and Italian harbors, is already at work in Cherbourg, together with Army engineers and British experts.

Nothing the Germans were able to do can prevent us from using the sheltered anchorages inside the Cherbourg breakwaters. A great granite breakwater 650 feet wide on a rubble base and 20 feet wide at the top protects the outer roads; smaller breakwaters give added protection in the inner harbor. The measurements of the entrances to the outer breakwater are one and a half miles by three-quarters; the outer harbor was not and probably could not be blocked completely.

The docks and unloading facilities may be wrecked, but they are of far less importance than the breakwater, for a sheltered anchorage for our ships and relatively smooth water for our small craft are what the Allies need, as last week’s gale proved.

Gateway to France

We now have that anchorage. That is to say, we shall shortly have a gateway into France through which supplies and reinforcements can be sent continuously in greater and greater quantity regardless of the weather. In addition to the facilities of Cherbourg, we have our landing beaches, over which so far, a truly phenomenal number of men and tons of equipment have been landed, and the small but important facilities of a dozen little ports between Cherbourg and the Orne River.

All this means that our foothold in France is now absolutely secure. Regardless of enemy counterattacks that may yet develop the Germans can no longer hope to throw us into the sea.

It was not possible to make such certain statements until Cherbourg was captured. Even a more protracted defense of that port by the enemy, if coupled with more bad weather, might have proved embarrassing to us.

Now we are certainly in France to stay. The Germans will try – and may be able – to contain our beachheads and to bottle us up in the Cotentin Peninsula in a sort of second Anzio, but they cannot expel us. That in itself is a great, probably a mortal, blow to German strategy.

The capture of Cherbourg means, therefore, in my opinion, the beginning of the end in Europe. It does not mean the end; a battle has been won, not the campaign. But the French, Russian and Italian offensives and our air bombardments are great hammer blows toward that end.

The enemy will try to prolong the agony of war. But after Cherbourg, the knowledge of the bankruptcy of German strategy must become more and more evidence to the German people.