The New York Times (June 7, 1944)

HITLER’S SEA WALL IS BREACHED, INVADERS FIGHTING WAY INLAND; NEW ALLIED LANDINGS ARE MADE

All landings win; Our men are reported in Caen and at points on Cherbourg Peninsula

Big air armada aids; 10,000 tons of bombs clear the way – poor weather a worry

By Drew Middleton

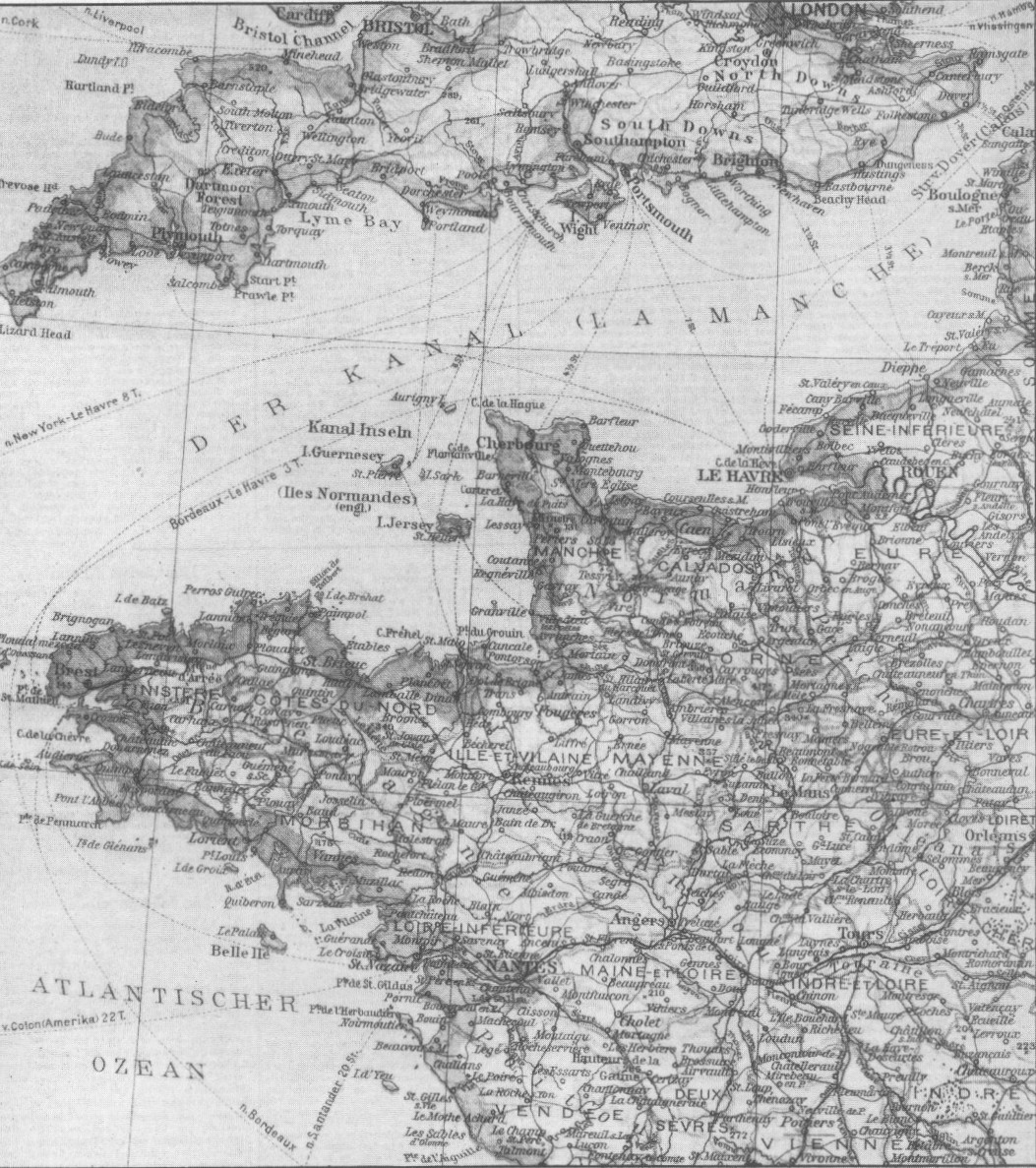

Allied troops make good their landings in northern France

After parachutists had descended at Barfleur (1), according to enemy sources, amphibious forces converged on Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue, just to the south, and are said to have straddled the Valognes-Carentan road (2). More airborne landings were reported made around Isigny (3), at the mouth of the Vire River, and troops went ashore near Arromanches (4). Allied forces, beating inland, fought in Caen (5). They captured Honfleur (6), said Berlin, and then fanned out south and east toward Pont-l’Évêque, Beuzeville and Pont-Audemer. The Paris radio spoke of fighting north of Rouen (7). In addition to the invasion of the mainland, the Allies were reported by the enemy to have landed in force on the Channel Islands of Guernsey (8) and Jersey (9).

SHAEF, England –

The German Atlantic Wall has been breached.

Thousands of U.S., Canadian and British soldiers, under cover of the greatest air and sea bombardment of history, have broken through the “impregnable” perimeter of Germany’s “European fortress” in the first phase of the invasion and liberation of the continent.

Communiqué No. 2, issued at the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, before last midnight, reported that all initial landings, which had earlier been located on the coast of Normandy, in northern France, had “succeeded.” The Germans told of heavy fighting with Allied airborne troops in Caen, road and railroad junction eight and a half miles inland from the Seine Bay coast, and the enemy said there was heavy fighting at several points in a crescent-shaped front reaching from Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue, on the west, to Le Havre, on the east.

The German Transocean News Agency said early Wednesday that the Allies had made “further landings at the mouth of the Orne under cover of naval artillery,” according to the Associated Press. The agency said “heavy fighting” was raging.

A British broadcast, recorded by Blue Network monitors, said Wednesday that “another airborne landing south of Cherbourg has been reported.” Another British broadcast said that Allied bulldozers were busy “carving out the first RAF airfield on the coast of France.”

At last midnight, just over 24 hours after the beginning of the operation, these were the salient points in the military situation:

-

Despite underwater obstacles and beach defenses, which in some areas extended for more than 1,000 yards inland, the Atlantic Wall has been breached by Allied infantry.

-

The largest airborne force ever launched by the allies has been successfully dropped behind the Atlantic Wall and has attacked a second echelon of German defenses vigorously. The Germans estimate this force at not less than four divisions, two American and two British, of paratroops and airborne infantry.

-

Most of the German coastal batteries in the invasion area have been silenced by 10,000 tons of bombs and by shelling from 640 naval ships. The shelling was so intense that a British destroyer, HMS Tanatside, had exhausted all her ammunition by 8:00 yesterday morning.

-

Against 7,500 sorties flows from Monday midnight to 8:00 a.m. Tuesday, by the Allied Air Forces during the first day of the invasion, the Luftwaffe has flown 50, and the main weight of the enemy air force in the west (estimated at 1,750 aircraft) has not entered the battle.

-

The first enemy naval assault on the Allied invasion armada was beaten off with the loss of one enemy trawler and severe damage to another.

There is reasonable optimism at this headquarters now, but there is no effort to disguise concern over several factors, among them weather and the shape of the first major German counterblow.

Navies 100% effective

Adm. Sir Bertram Ramsay, Allied naval commander-in-chief, declared the Allied navies had “in effect” been 100% successful in the task of landing the invasion troops in France. These troops have now become the most important of the fighting services involved in the invasion, for there are indications that the enemy to some extent is withholding reserve formations for a general counterattack once he is certain yesterday’s landings constitute the main threat in Northwestern Europe.

The heaviest fighting in a 100-mile battle area appeared to revolve around Caen, according to the German news agency DNB. The enemy also admitted the establishment of an Allied bridgehead on both sides of the Orne estuary, and another in the area northwest of Bayeux, and the Germans said an Allied paratroop formation had a firm grip on both sides of the Cherbourg-Valognes road.

A group of light Allied tanks and armored scout cars was placed northeast of Bayeux by the enemy (Bayeux is about six miles inland from the southwest shore of the Seine Bay). Earlier, Allied tanks had been reported fighting in the area of Arromanches on the south coast of the Seine Bay. This group was attempting to join the main beachhead forces northwest of Bayeux, the enemy said.

A German military spokesman reported 15 cruisers and 50-60 destroyers were operating west of Le Havre last night covering a large number of Allied landing craft. The two naval task forces that led the invasion were commanded by RAdm. Sir Philip Vian, who won fame while commanding the destroyer HMS Cossack early in the war, and RAdm. Alan Goodrich Kirk of the U.S. Navy. The two naval forces plus a third force, which came from the north, included one 15-inch gun battleship (the HMS Warspite), an American battleship (the USS Nevada, a veteran of Pearl Harbor), the cruisers USS Augusta and USS Tuscaloosa and the British cruisers HMS Mauritius, HMS Belfast, HMS Black Prince and HMS Orion, and shoals of destroyers flying the Stars and Stripes and the White Ensign.

Steaming through the English Channel, swept by 200 British minesweepers, the men o’ war escorted thousands of landing craft, transports and assault craft bearing Gen. Sir Bernard L. Montgomery’s landing forces to the beaches.

Shortly before the first soldiers “hit the beach,” three German torpedo boats and an undisclosed number of armed trawlers attacked. They were driven off with withering fire. One trawler was sunk and another severely damaged.

Then the destroyers turned their guns on enemy defenses, while the ships engaged enemy batteries already battered by high explosives dropped from the air.

The large airborne forces that were dropped and landed in the night were already assembling behind the Atlantic Wall as the first troops scrambled up the beaches. Dawn was the climax of the first phase of the invasion. Wave after wave of U.S. bombers – at least 31,000 Allied airmen were in the air between Monday midnight breakfast Tuesday – took up the task of flattening the German defenses and silencing guns. Fighters circled over the beachheads on defensive patrol, while fighter-bombers darted inland to attack German troops moving up to attack the airborne and seaborne invaders.

So feeble was the German Air Force opposition that one fighter force swept 75 miles inland without meeting opposition. In one of the few clashes, 300 Marauders ran into 20 Fw 190s, destroying a single enemy plane without loss. A great fleet of more than 1,000 planes, including gliders and towplanes, went almost unmolested when it carried the airborne force to its objectives, while some Flying Fortress groups reported neither fighter interference nor flak fire.

All day the weather forced medium and light bombers to attack at low level, 300 Marauders bombing from 3,000 feet during yesterday afternoon. Havocs on a similar attack jumped and halted a column of eight German armored cars. Road junctions and railway yards behind enemy lines were bombed repeatedly.

Allied integration of arms

Yesterday’s operations, the greatest yet undertaken by the Western powers, were marked by a complete integration of all striking arms. Tens of thousands of bombs and shells tore at the German defenses as air force and navy gave maximum support to the infantrymen struggling ashore or the airborne forces attacking the “Atlantic Wall” from the rear.

The Bomber Command of the Royal Air Force, the first Allied forces to strike at the heart of Germany in this war, had the honor of opening the assault. At 11:30 Monday night, the first of ten waves of Lancasters and Halifaxes swept in from the sea to begin bombardment of the German batteries along the French coast.

There were more than a hundred bombers in this and subsequent waves, and the total number of “heavies” involved was more than 1,300. Since on such a trip each of these heavies can carry at least five tons of bombs, the batteries were hit by around 7,000 tons of bombs before the sun rose to reveal the great invasion fleet gently rolling on the choppy waters of the English Channel.

The batteries attacked were of two types, with two different functions. There were long-range rifles – mostly 155mm and 177mm weapons – to engage shipping far out at sea. Equally important to the success of the landing were batteries of heavy howitzers sited on beaches or on areas just off the beaches where landing craft might congregate. Both types of batteries were strongly protected, with most of the 155s in casemates of reinforced concrete. The howitzers were in sandbagged emplacements or newly-constructed casemates.

The preliminary air attacks appear to have been successful, for reports from the front stressed the failure of German batteries to maintain determined fire. Many of the casemates were blown apart, while some of the howitzers were knocked over by the blasts and their gun pits were smothered with dirt torn up by the bombs.

This destruction was well underway by dawn yesterday, when more than 1,000 Flying Fortresses and Liberators of the U.S. 8th Air Force roared out from Britain to maintain the bombing. At the same time, far out at sea, gunfire flickered along the decks of battleships, monitors, cruisers and destroyers as they engaged not only gun batteries but strongpoints and blockhouses along the Normandy beaches.

By this time, troop carriers and gliders of the U.S. 9th Army Air Force and the RAF had flown paratroops and airborne infantry to their objectives and the two-sided battle of the so-called Atlantic Wall had begun on the ground as well as in the air and at sea.

All day the big guns roared from the sea to shore and from the shore to sea. All day Liberators, Fortresses, Marauders, Mitchells, Typhoons, Havocs and Thunderbolts of the Allied Air Forces bombed the German coastal defenses and troop concentrations sheltered in the lush orchards of Normandy.

All day Allied fighters patrolled the battle area and spread an air umbrella above the invasion fleet.

Air Chief Trafford Leigh-Mallory, Gen. Eisenhower’s deputy commander for air, was so proud of the work done by yesterday morning while the battle was still developing, he congratulated his forces on the “magnificent work… done in preparing for the invasion.”

As this order was flashed to the far-flung squadrons of the RAF and USAAF, the battle on the ground, where it will eventually be fought and won, was beginning with the first airborne landings. According to enemy radio reports, these were made “in great depth” in the area of the Seine Bay. British airborne units were dropped in the Le Havre area, while Americans floated to earth in the Normandy district.

The enemy has already identified the British 1st and 60th Airborne Divisions and the U.S. 82nd and the 101st Airborne Divisions, according to Axis broadcasts. Airborne troops landed at Barfleur, east of Cherbourg; Carentan, five miles from the Seine Bay on the Cherbourg Peninsula, and northeast of Caen between the estuaries of the Seine and Orne, the Germans said.

Air and naval losses for the first day were considered remarkably low at this headquarters, although it was emphasized the enemy had not attacked strongly in either element. One U.S. battleship, risking unswept mines and shore torpedo tubes, moved in to short range in order to silence a troublesome battery that was holding up operations with its fire.

The Allied seaborne landings began to develop along the coast of Normandy at the same time. The Germans placed the first attacks between the mouths of the Seine and the Vire, a stretch of coast about 75 miles long, beginning in the east at Trouville and Deauville, once filled with holiday crowds from all over Europe, and reaching to the Bay of Isigny in the west. The stretch of coast is the nearest to Paris and is connected with the capital by good rail and highway communications.

U.S. tanks poured ashore in the area of Arromanches, a small fishing village about 15 miles northwest of Caen, and Asnelles, in the middle of the Seine Bay south coast, the Germans said, adding that 35 tanks had been destroyed in the fighting around Asnelles. What the Germans described as “particularly extensive landings” were also made at the small coastal village of Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue, close to the tip of the Cherbourg Peninsula. The enemy also claimed the Allies had landed on Guernsey and Jersey in the Channel Islands, the last bit of the British Empire held by Germany. As the infantry scrambled over the beach obstacles from the sea, airborne invaders were fighting a hot battle in the district of Caen, according to the enemy reports. Caen lies on the main railroad line running from Cherbourg to Rouen, Évreux and Paris and is a junction of nine highways. Other large airborne concentrations were around Le Havre and Cherbourg, and the enemy claimed they had been made in order to seize those ports for the invasion fleet.

The enemy claimed a battleship had been badly damaged and a cruiser and large transport sunk during a duel between shore batteries and the Allied naval escort. The enemy put the escort at six battleships and 20 destroyers, with well over 2,000 landing craft (some of them of 3,000 tons) participating in the landings along the Seine Bay.

Enemy claims hits

President Roosevelt said at his Tuesday press conference that Gen. Eisenhower had reported the loss of two U.S. destroyers and one LST, a tank-carrying landing ship.

Seaborne landings overcame intricate and elaborate German obstructions, mainly because Gen. Eisenhower took a chance and landed his forces at low tide when naval engineers’ parties could deal with underwater obstacles. These included mines moored below the low-water line, beach mines and hundreds of obstacles. The latter included a section of braced fences, concrete pyramids, and wood and steel “hedgehogs.”

All these obstacles were extensively mined, either with Teller mines or specially prepared artillery projectiles. But before the invasion armada could reach these defenses some 200 Allied minesweepers manned by 10,000 officers and men had to sweep a passage through extensive minefields with which the enemy had masked the approaches to the beaches.

It was officially called the biggest and probably the most difficult, certainly the most concentrated, minesweeping operation ever carried out. The most delicate and dangerous work was done at night in a cross-tide of two knots.

When dawn came, the landing craft moved slowly toward the beaches through the swept channels, and the minesweepers, were sweeping new areas.

It was through this sort of sea defenses that the invasion ships had to make their way before they grated on continental beaches.

Ashore the engineers and infantry found a variety of new obstacles. The entire beaches were guarded by bolts of wire. The exits from the beaches were blocked by an adaption of existing seawalls to become anti-tank walls, and steel obstacles were set up. Anti-tank ditches 50-60 feet wide were extensively employed and minefields had been laid up to a depth of more than 1,000 yards from shore, while inundations were employed wherever the ground was suitable.