Old minstrels used cigar boxes, tin cans to make instruments

By Douglas Gilbert, Scripps-Howard staff writer

Second of a series.

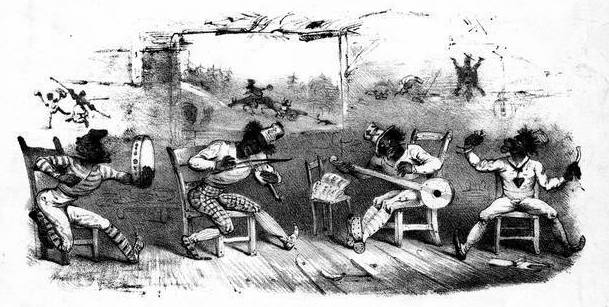

A panel from a minstrel song cover (“Going Ober de Mountain”) dated 1843, the inauguration year of minstrelsy in America. It probably caricatures an act from the Virginia Minstrels, the first organized troupe. The song cover is a superb lithograph and a collector’s item.

Who devised the peculiar formation of the minstrel show’s first part, as the opening was called – the semi-circular arrangement with the performers (“40-Count-‘Em-40”) banked in tiers – is not known. Doubtless it was a gradual development. Certainly, it was a logical grouping, for the stages of the ‘70s, ‘80s and ‘90s, the decades when the minstrel show was most popular, were small and poorly lighted.

The late Brander Matthews, one-time professor of dramatic literature in Columbia University, offered an interesting theory as to the origins of Bones and Tambo, the end men, and the pompous interlocutor, or middleman.

For his originals, Mr. Matthews went back to 16th-century Paris and the dialogue between Mondor, the quack, and his comic foil, Tabarin, buskers of the period, or, in the true sense of the word, minstrels.

Setting up a pitch in the marketplace, Tabarin would inquire of the doltish quack:

Master, tell me which is the more generous, man or woman?

Mondor replied:

Ah, Tabarin, that is a question often debated by the philosophers of antiquity and they have been unable to decide which is truly the more generous, man or woman.

Tabarin said, briskly:

Never mind the old philosophers. I can tell you.

What, Tabarin, do you mean to say you can tell us which is the more generous, a man or a woman?

Certainly.

“Pray do so then,” said Mondor.

The judgement? Shush

Then Tabarin would announce his judgment which, unfortunately, is too ribald to be printed today but which, in picklock Paris of the 16th century, was greeted with guffaws by the unsqueamish crowd about the quack doctor’s platform.

Although this smacks a bit of the medicine show, Matthews’ analogy is not too farfetched. The minstrel interlocutor was as fatuous as Mondor, and the end men as glib, if not as bawdy, as his Tabarin.

“You ask me, Mr. Bones, why did the chicken cross the road. And now, I ask you, why did the chicken cross the road?” Thus, the minstrel interlocutor. Eventually he was answered and the laugh (and the audiences really laughed at this) was on the pompous interlocutor.

Personal jokes

Sometimes the comedy was personal, even to the use of the performers’ real names. And sometimes either one of the end men, instead of the interlocutor, was the butt of the joke.

The San Francisco Minstrels, one of about 50-odd minstrel troupes in the late ‘80s, was headed by Billy Birch, Dave Wambold, Charlie Backus and Ad Ryman. The latter was the interlocutor; Birch and Backus were end men.

During the First Part (this designation was always capitalized), Birch would tell Ad Ryman of how Backus tried vainly to impress a pretty girl at a party.

Birch would say:

And do you know, Ad, she turned to him and said, “Mr. Backus, is that your real mouth or do you use glove stretchers?”

Backus had a mouth like a cavern.

Two ran for 40 years

This bucolic flavor was essentially minstrel and its greatest exponents were Carncross & Dixey’s Minstrels. In a bandbox theater in 11th Street below Market in Philadelphia, they established an unusual reputation – for 40 years they prospered.

Prospered, that is, in the same place and with the same organization. J. L. Carncross, the interlocutor, had a light tenor voice splendidly adapted to plaintive ballads – “The Low-Backed Car”, for example, or “When the Corn Is Waving.”

E. F. Dixey, his partner, was the bone end and his forte was “bone” solos played with two clappers of bone of ebony in each hand. He imitated barbers, woodchoppers and shoemakers and closed with a rousing interpretation of the race between Dexter and Goldsmith Maid, two famous trotters of the period.

Refinement of art

Dixey’s bone solos were a refinement of the art. The earliest end men used the jawbone of a horse. They rattled a rib bone between its forks to produce rolls and single and double clacks. Often, they accompanied an ancient bit of doggerel recalled by Jack Murphy, old-time vaudeville star:

Jawbone walk, jawbone talk,

Ain’t goin’ to work no more.

Jawbone eat with a knife and fork,

Ain’t goin’ to work no more.

Rain little, snow little,

Ain’t goin’ to work no more.

Hailstorm! Blind hawg,

Ain’t goin’ to work no more.

The bone solo was virtually a Carnegie Hall interlude for the minstrel show. Performers used many freak instruments, mainly of their own devising. Murphy & Mackin, an outstanding team, perpetuated the greatest novelty of minstrel times. They played a reel on the ribs of a human skeleton, and rigged it so the skeleton danced the last few bars.

Cigar boxes used

Fiddles and banjos made of cigar boxes were common. But a performer named Dilks played a tune on a tomato can. This also was a feat. He attached a string to the can, held the can between his feet and vibrated the string by scratching it with a rosined stick. He accomplished the musical scale by changing the tension of the string.

Then a team named Huber and Glidden developed the idea. They make a fiddle and banjo out of oyster cans. In those days, oysters were packed in tins about the size of a two-pound candy box. The team was so successful they billed themselves as the “Oyster Can Mokes.”

For contrast, Glidden would then play a real banjo. But Huber kept to his freak role. As Glidden strummed in orthodox manner, Huber played a whisk broom obligato all over Glidden, all over his banjo and all over the chair Glidden sat in.

Minstrel comedy musical acts ran the gamut, stopped nowhere. Performers made “musical” instruments out of crockery, bottles, flowerpots. One team even used top hats for tonal effects by stiffening them with shellac and spanking them with a paddle.

Johnny Saunders devised an act with eight beer kegs which he tapped for tunes with a bungstarter. He tuned the kegs with water, exactly as musical glasses. Fields & Hoey played “The Last Rose of Summer” on eight cowbells. And Jack Keating, of Keating & Sands, actually played a tune of his face. He played the “Carnival of Venice” by forcing the wind across his lips with a bellows. It sounded like a far-off steamboat whistle.

Tops in freak minstrel music, though, was Swain Buckley. He billed himself as “The One-Man Band,” and it was no understatement. Buckley tied a brass drum to his back, held cymbals between his knees, fastened bells to his head and ankles, fixed a harmonica on racks close to his mouth, held an accordion in his hands and strapped a snare drum about his waist.

Playing the accordion and using every joint and muscle in his body, he managed to play a march and several popular melodies of the day.