The Pittsburgh Press (February 8, 1944)

Old-time minstrel show prospered for 60 years then faded out entirely

By Douglas Gilbert, Scripps-Howard staff writer

First of three articles.

This is the centenary of the minstrel show, and where is there one troupe to celebrate it? It is amazing that so vast an expression, which beguiled millions of Americans from 1843 to the turn of the century, should have left its mark nowhere in the contemporary theater.

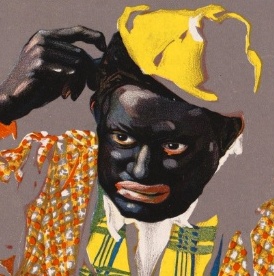

Vaudeville still prevails, sometimes in revival, and in our nightclub floorshows, where a semblance of the old two-a-day theater exists. The circus still heralds New York’s spring. But no ghost in blackface haunts our stage. Nothing is left of the minstrel technique.

Minstrelsy, the only theatrical entertainment indigenous to the United States, has been dead for years. George M. Cohan rattled its bones in the season 1908-09 with the Cohan & Harris Minstrels. He took the troupe on tour and Charlie Washburn, his drumbeater, says it cost Cohan $100,000. In 1930, Kilpatrick’s Old-Time Minstrels played briefly at the Royale Theater. No producer brave, or stupid, enough has attempted a revival since.

Some phases of minstrelsy are surprising. Its entire presentation was based on blackface and the Negro’s folkways and songs. Yet the Negro had little or nothing to do with its form. It originated with and was developed by white performers.

Dixie is sole survivor

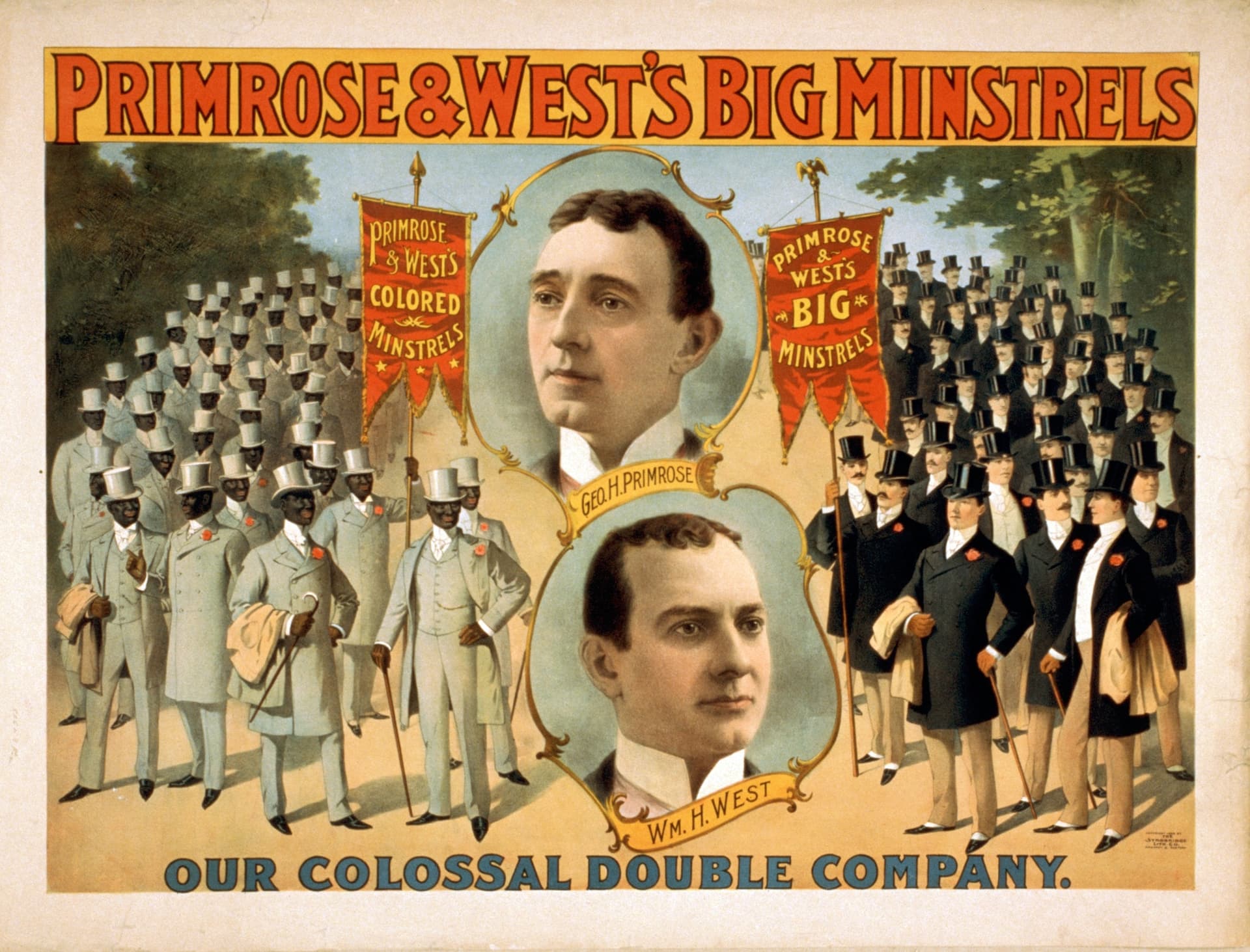

The late George H. Primrose, a blackface star for 50 years, said that the first production of a minstrel show was given at the Bowery Amphion, Feb. 6, 1843. The performers were Dan Emmett, Frank Brower, Billy Whitlock and Dick Pelham.

Only Emmett is remembered – through his song, “Dixie.” Even “Dixie” had nothing to do with the South except through the allusion in its lyric. Emmett wrote it in New York on a blustering winter’s day and he really meant the line, “I wish I was in the land of cotton.” He wrote the song for a “walkaround,” the invariable finale to the minstrel show’s first part.

Dan was 80 and had long lived in retirement on a small farm near Mount Vernon, Ohio, when Al G. Fields, a popular minstrel manager and performer, induced Dan to travel with his show in 1895. Dan rode in the street parade in an open barouche with banners on its side proclaiming, “Dan Emmett – Composer of Dixie.”

He was introduced to the audience after the first party walkaround, then the band played “Dixie” with the inevitable response while Dan bowed feebly. He was a good draw, but troublesome to care for on the road, and Fields only took him out that one season.

Fields evades New York

Fields was an interesting fellow, seemingly took delight in proving his amusing quirks. One of them was that he would never play New York. He always felt that New York audiences wouldn’t care for his style of playing, and he was right.

One season in the late ‘90s, he was persuaded against his better judgment to fill an engagement at the Grand Opera House. The attendance was miserable and on the last night, Primrose, Billy West, Lew Dockstader and several other prominent minstrels took a stage box to cheer him up. Before the final curtain, Fields stepped to the footlights and said:

Ladies and gentlemen, take a good look at me because you are not ever going to see me again.

They never did, in New York.

Neil O’Brien

Neil O’Brien, who at 75 is probably the oldest living minstrel, confirms Primrose’s statement that the first minstrel show was given in 1843 by Emmett, Whitlock, Brower and Pelham. He says they met at a boarding house and fixed up a musical act with songs and funny sayings and then worked the pubs for throw money. They were successful and the engagement at the Amphion followed.

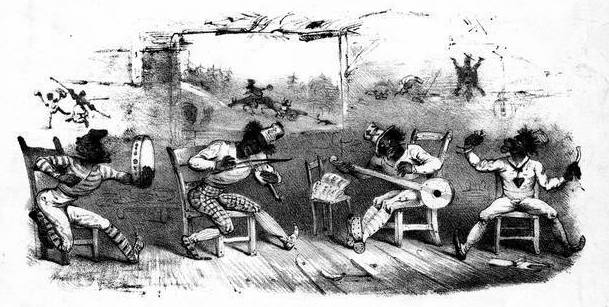

Emmett was a fiddler, the others played bones, tambourine and banjo. Throughout its years of public presentation, the banjo has always been the musical symbol of minstrelsy – another curious phase of the entertainment.

That the banjo was the instrument of the Southern Negro – and thus the proper heritage of minstrelsy – has been disputed, and with authority.

Banjo idea disputed

I have seen the Negro at work and I have seen him at play. I have attended his cornhuskings, his dances and his frolics. I have heard him give the wonderful melody of his songs to the winds… I have heard him scrape jubilantly on the fiddle. I have seen him blow wildly on the bugle and beat enthusiastically in the triangle. But I have never heard him play on the banjo.

The words are those of Joel Chandler Harris.

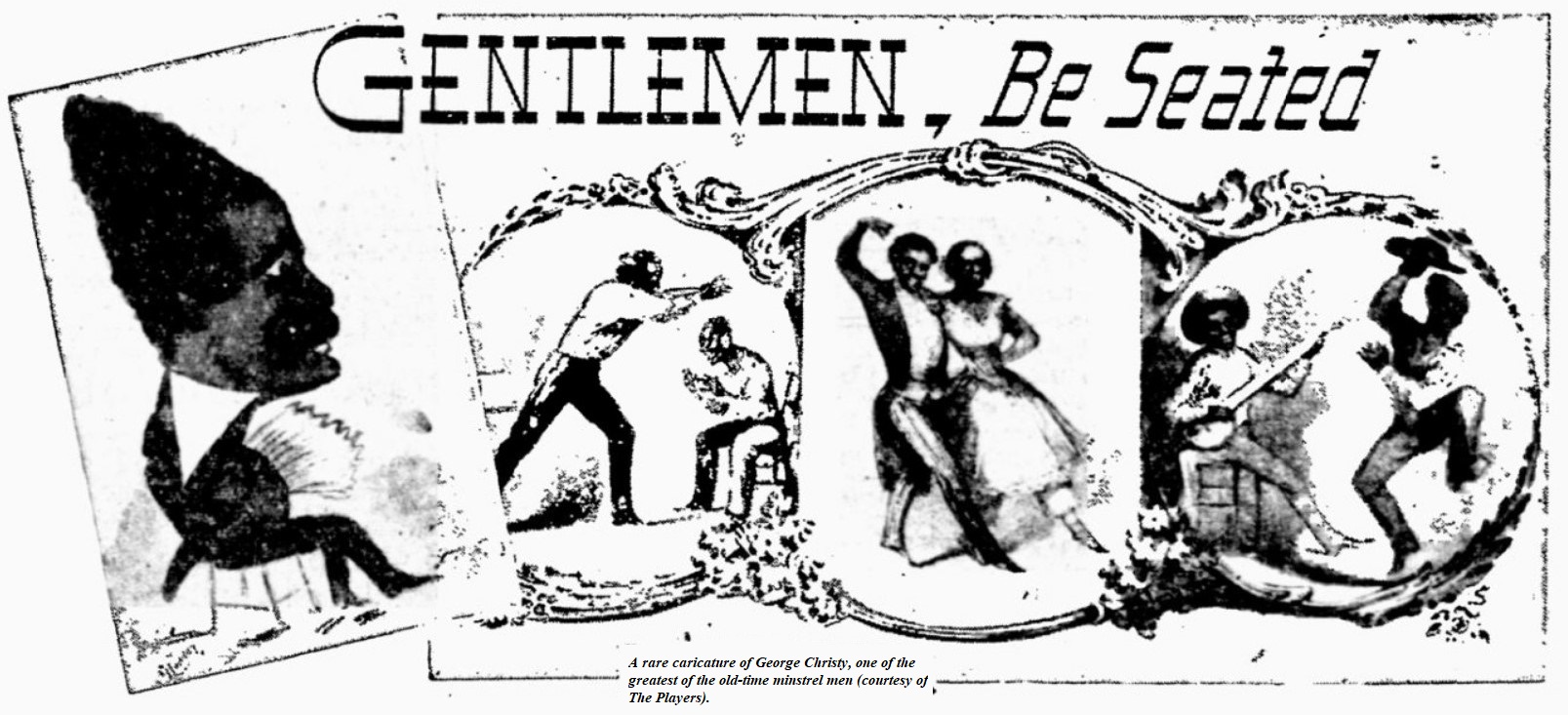

One of the great and most popular shows in the history of minstrelsy, George Christy’s Minstrels, featured the banjo. Christy, a pioneer, lasted for years and made much money. His was the first minstrel troupe to invade England. The British took to the entertainment at once and minstrel shows were a pronounced success in England for years.

It is too easy, across the years, to disparage the minstrel show. Against the speed and sophistication of our own revues and musicals, it was a doddering, awkward entertainment with silly grimaces and sillier jokes.

But its bombast was good-natured, its jubilation sincere. Throughout its 80-odd years of life, it was a family show. Indeed, its performers accented its appeal to children with gawdy uniforms, the blare of brass in the time-honored 11:45 a.m. parade, and with nursery jokes of the why-did-the-chicken-cross-the-road type.

Shady jokes rare

Its entertainment was couched, not to the morals of its times, which were no better than ours, but to the mores, which were vastly different. A respectable woman of the ‘70s, ‘80s and ‘90s publicly exposed two anatomical parts – her hands and her face. In the legitimate theater, allusions to the female form were sparse and guarded.

In the minstrel show, they scarcely existed beyond the mention of “a pretty girl.” No women appeared in the strict form of the minstrel show, it was masculine nonsense solely. Moreover, minstrels, playing to a mixed audience that included children, were forced to keep it clean. Eventually this became the tradition. A “blue” joke or sexy double entendre in a blackface show was rare.

Because of its crazy quilt hit-or-miss pattern, the minstrel show developed an amazing assrtoment of curious characters, some of whom could do nothing else but clown in blackface. Charlie Reynolds was unique.

Reynolds, who worked for Simmons & Slocum Minstrels, could neither sing nor dance and he was tone deaf. He could never learn more than a few words of any song. He could handle neither tambourines nor bones, and when telling a story, he collapsed helplessly before reaching its point.

Arresting personality

But he had an arresting personality and an irresistible humor and his sway over an audience was complete. His dialogue, method and style, as old-timers recall them, were infantile, sometimes insane. But he was a popular performer. He died in Vineland, New Jersey, 40 years ago in the poorhouse.

Lew Simmons was one of the friendliest and best-liked men in the profession. It may surprise most baseball fans that Lew, not Connie Mack, was the first manager of the Philadelphia Athletics. The fact is commemorated in an old song by H. Angelo called “The Baseball Fever,” which was published in 1867.

The humor of any situation was the first thing Lew saw, even if the joke was on him. He was born in Reading, Pennsylvania, and there he died on a visit – struck down and killed by a beer truck. Doubtless Lew drew a celestial chuckle out of that. He was a great guzzler.