8th August 1942

Atlantic Ocean : Battle of Slow Convoy SC-94 continues. German submarines U-379 and U-176 intercepted and attacked Allied convoy SC-94 485 miles southeast of the southern tip of Greenland in the afternoon; at 1325 hours. Under night attack the convoy ranks fell into chaos , some merchant ship crews prematurely abandoned their ships then reboarded them , U-379 torpedoed and fatally damaged British merchant ship Anneberg (that sank later in the day) and sank US merchant ship Kaimoku (50 survived); at 1518 hours, U-176 torpedoed and sank British merchant ship Kelso (3 were killed, 40 survived), sank British merchant ship Trehata (23 were killed, 25 survived), and disabled Greek merchant ship Mount Kassion which sank next day (47 survived).

In exchange Royal Navy corvette HMS Dianthus counterattacked U-379 by ramming and depth charges, sinking the German submarine; 40 were killed, 5 survived.

Later that afternoon, a masthead lookout on the Royal Navy corvette HMS Dianthus, commanded by C. E. Bridgeman, spotted two German submarines about six miles away. Bridgeman immediately fired twelve rounds from his main 4″ battery, but none hit and both submarines dived. Combing the area for several hours, HMS Dianthus finally regained contact with German submarine U-379 and fired off eight star shells. U-379 dived instantly, but her evasion was inept and HMS Dianthus blew him back to the surface with five well-aimed depth charges. When U-379 popped up, HMS Dianthus fixed the boat in her searchlight, dropped five more depth charges, and slewed about to ram, with all guns blazing. Firing snowflakes to illuminate the scene, HMS Dianthus crashed into the forward deck of U-379, rode over the U-boat, and dropped five more shallow-set depth charges. These explosions forced crew of U-379 to scuttle and abandon ship. As German crew were leaping into the sea, Bridgeman pumped another seven rounds of 4″ shells into the U-379, raked her with machine-gun fire, and rammed her three more times. After midnight on August 9, German submarine finally upended and sank , only five of her crew survived and picked up by HMS Dianthus.

German submarine U-98 mined waters off Jacksonville, Florida, United States.

Bay of Biscay : Italian submarine Morosini became missing with all hands due to unknown reasons in the Bay of Biscay west of France.

Cairo , Egypt : General Claude Auchinleck officially relieved from Commander in Chief Middle East. Churchill’s military secretary, Colonel Ian Jacob, was sent with a letter from Churchill informing Auchinleck of the decision and demanding a reply whether he would accept the new Iraq-Iran Command being offered. Jacob, carrying the fatal letter, felt “as if I were just going to murder an unsuspecting friend.” Jacob was deeply impressed with the calm manner with which Auchinleck received the news that ended his military career as a field commander. But both Churchill and Brooke had lost faith in Auchinleck, and the New Zealand official history records that “there is no record of a single voice being raised on [Auchinleck’s] behalf.

El-Alamein , Egypt : Rommel calculated that he had the resources for one ‘last‐chance’ attack on Auchinleck’s line at El Alamein. It had to succeed because after that the 1400 tons of fuel captured in Tobruk would be gone and there was insufficient coming down his extended supply line to sustain any further action. If he could break through the Eighth Army he could take Cairo and the port of Alexandria, his supply problems would be eased and the Suez Canal would be within reach. He told Lucie that ‘I must make best use of the next few weeks to prepare for it.’ He would attack on 30 August. ‘If this blow succeeds it could in part decide the whole course of the war.’

German–Italian partnership was about to take another big dip in North Africa. Following his failure to break through the Alamein Line, on 12 July Rommel wrote a report to the Army Operations Department and referred to ‘alarming symptoms of deteriorating morale’ in the Italian ranks. The Italian Pavia and Brescia Divisions had been all but wiped out in the recent fighting and Rommel claimed that ‘several times lately’ the Italians had deserted their positions. As a result, Rommel was pleading for more German troops.

When the Italians learned about this report it went down very badly indeed, not least with the newly promoted Maresciallo Ettore Bastico, the senior Italian commander in North Africa, and with Mussolini, who had given up waiting to march into Cairo on his charger and had gone back to Italy. During his three weeks in Libya, Rommel had not called on him once – justifiably, since he’d been in the thick of battle, but such excuses didn’t really wash with Mussolini. ‘Naturally,’ noted Count Ciano, ‘Mussolini has been absorbing the anti-Rommel spirit of the Italian commander in Libya, and he lashes out on the German marshal.’ The attitude of German troops was also, apparently, obnoxious. ‘The tone of the Duce’s conversation,’ noted Ciano a few days later, ‘is increasingly anti-German.’

Mediterranean Sea : Royal Navy submarine HMS Turbulent torpedoed , shelled and destroyed the hulk of Italian destroyer Strale, which had run aground intentionally on 21 Jun 1942, after being attacked by RAF torpedo bombers, to prevent sinking.

Royal Navy submarine HMS Proteus sank German manned Greek sailing vessel Firesia with her deck gun in the Aegean Sea south of Naxos island, Greece.

Gibraltar : On Saturday night, August 8, there were seven ships from Operation Pedestal refueling in Gibraltar, enough that Admiral Burrough called a midnight meeting of their captains. In the nearby neutral Spanish town of Algeciras, two Royal Navy officers finished their late dinner and on their way out passed a German sitting at a table.“Today we see you,” the German told the officers with a knowing smile. “You sail out and you sail back, you sail out and you sail back. Then you will sail out and don’t come back. Then we go out and get you.”

Voronezh Front , Russia : The Soviet Army launched a counter-offensive of Voronezh under Marshal Timoshenko.

Kalach , Don River , Russia : Sixth German Army captured Surovikino , slowly destroying Soviet 62nd Army by severing its rear to Don river.

Caucasian Front , Russia : German panzers from First Panzer Army drive into Piatigorsk, and fight it out with Soviet political police and a women’s signal detachment. German troops short on fuel stumble into a convoy of Soviet American- made trucks loaded with gasoline, and keep on going.

Norwegian Sea : Soviet submarine M-173 was lost in Norwegian Sea for unknown reasons

Vichy France : The Vichy French make the possession of explosives a death- penalty offense.

London , UK : General Dwight Eisenhower established his headquarters in England, United Kingdom.

On 7 August, Ike lunched in his flat with General Harold Alexander, recently back from leading the British retreat from Burma, and designated as Mediterranean and Middle East Commander in Chief; General Patton had been pencilled in to lead the US forces. Ike’s aide Harry Butcher believed this was an important lunch for Ike. Alexander had about as much battlefield experience as any soldier in the British Army, while Ike was not only junior in rank but had no combat experience at all, let alone any battlefield command. ‘There was,’ commented Butch, ‘the touchy question of how accessible Ike might be to Alexander.’ He needn’t have worried; the two got on well and as the British general left, he told Ike that he thought he had got off to a ‘good start’. Eisenhower also impressed with Alexander suave , cool , confident and diplomatic behavior , later taking him as one of his role models as Supreme Commander.

A telephone call from the War Office on 8 August ordered General Bernard Montgomery to proceed immediately to Egypt to take command of Eighth Army at El Alamein. A B-24 Liberator bomber was standing by to fly him and one ADC out that evening, first to Gibraltar, then on to Cairo. Monty arranged for his stepson to stay with Major Reynolds and his wife. He warned them that ‘David’s grandmother will want him to go and stay for his holidays. On no account is he to go. She is a menace with the young.’

Bombay , India : The Bombay session of the All India Congress Committee passed the Quite India resolution, and Mahatma Gandhi gave the Quit India speech at Gowalia Tank park in central Bombay.

Kokoda Track , Papua New Guinea : At Papua, New Guinea , three companies of Australian 39th Battalion departed Deniki separately shortly after dawn to attack the Kokoda village.

A brief lull in the fighting along the track followed before the second engagement around Kokoda took place over the period 8 to 10 August 1942. In the wake of the first engagement, both the Japanese and Australians had paused to bring up reinforcements. After sending the surviving members of ‘B’ Company back to Eora Creek, Major (later Lieutenant Colonel) Allan Cameron – the brigade major of the 30th Brigade – took command of the 39th Infantry Battalion and advanced from Deniki on 8 August with around 430 men, intent on recapturing Kokoda to re-open the airfield. At the same time, the Japanese force, which had grown to around 660 men with the arrival of the remainder of Hatsuo Tsukamoto’s 1st Battalion, 144th Infantry Regiment and supporting elements, began their advance on Deniki.

The two sides subsequently clashed along the main Kokoda Track around Pitoki, near Faiwani Creek, in an encounter battle. A see-sawing action followed over the next couple of days, in which the main Australian force, consisting largely of Captain Arthur Dean’s ‘C’ Company, was pushed back along the track to the battalion’s headquarters around Deniki. Dean was amongst those killed in the fighting and as the pursuers followed ‘C’ Company back to Deniki, Cameron hastily organised the defence of his headquarters, which had to fight off an attack over several hours. Elsewhere, ‘D’ Company, under Captain Maxwell Bidstrup, took Pirivi to the east of Eora Creek, thus placing pressure on the Japanese rear, while another Australian company – Captain Noel Symington’s ‘A’ Company – retook Kokoda, finding it practically undefended.

Guadalcanal , Tulagi , South West Pacific : US Marines captured the unfinished Japanese Lunga Point Airfield at Guadalcanal at 1600 hours without meeting any resistance (most Japanese troops and construction personnel ran to south and west of island , leaving behind food, supplies, intact construction equipment and vehicles, and 13 dead. 1st US Marine Dşivision would put these captured supplies in good use during incoming weeks) , which would later renamed Henderson Field by the Americans. The Marines are amazed to find intact three AA batteries, ammo dumps, radio stations, a refrigerating plant, an air compressor plant, vehicles, stacks of supplies - most of it intact. The Japanese have left behind their personal gear, cups and bowls of rice, meat stew and prunes at their mess tables. Marines find some beds neatly made, some dishevelled. The most important discoveries are a copy of the current version of the Japanese naval code – JN-25C – and an early Japanese radar set. Turner has this loaded on a transport for further study.

So far the Marine have done their job, seizing their objectives, but have run into trouble with command, coordination, poor maps, worse radios, and a lack of manpower to unload supplies on Red Beach

The US Marines also captured Tulagi (307 Japanese killed, 3 Japanese captured, 45 Americans killed) cleaned out remaining Japanese defenders from Tulagi, Gavutu, and Tanambogo (476 Japanese killed, 20 Japanese and Koreans captured, 70 Americans killed) islands in the afternoon. In Tulagi , during the night, the Japanese attacked the Marine lines five times, beginning at 22:30. The attacks consisted of frontal charges along with individual and small group infiltration efforts towards Edson’s command post, which at times resulted in hand to hand combat with the Marines. The Japanese temporarily broke through the Marine lines and captured a machine gun, but were quickly thrown back. After taking a few more casualties, the Marine lines held throughout the rest of the night. The Japanese suffered heavy losses in the attacks. During the night, one Marine—Edward H. Ahrens—killed 13 Japanese who assaulted his position before he was killed. Describing the Japanese attacks that night, eyewitness raider Marine Pete Sparacino said:

“… full darkness set in. There was movement to the front … you could hear them jabbering. Then, the enemy found a gap and began running through the opening. The gap was (sealed) when another squad closed the gate. Some Japanese had crawled within 20 yards of (Frank) Guidone’s squad. Frank began throwing grenades from a prone position. His grenades were going off 15 yards from our position (and) we had to duck as they exploded. The enemy was all around. It was brutal and deadly. We had to be careful not to kill our comrades. We were tired but had to stay awake or be dead.”

At daybreak on 8 August, six Japanese infiltrators hiding under the porch of the former British colonial headquarters shot and killed three Marines. Within five minutes, other Marines killed the six Japanese with grenades. Later that morning, the Marines, after landing reinforcements in the form of the 2nd Battalion, 2nd Marines (2/2), surrounded Hill 281 and the ravine, pounded both locations with mortar fire throughout the morning, and then assaulted the two positions, using improvised explosive charges to kill the Japanese defenders taking cover in the many caves and fighting positions throughout the hill and ravine. The individual Japanese fighting positions were destroyed with these improvised explosives. Significant Japanese resistance ended by the afternoon, although a few stragglers were found and killed over the next several days. In the battle for Tulagi, 307 Japanese and 45 U.S. troops died. Three Japanese soldiers were taken prisoner.

Most of the 240 Japanese defenders on Tanambogo were aircrew and maintenance personnel from the Yokohama Air Group. Many of these were aircraft maintenance personnel and construction units not equipped for combat. One of the few Japanese soldiers captured recounts fighting armed with only hand sickles and poles. Rupertus detached one company of Marines from the 1st Battalion, 2nd Marine Regiment on Florida Island to assist in assaulting Tanambogo, in spite of advice from his staff that one company was not enough. Incorrectly believing Tanambogo to be only lightly defended, this company attempted an amphibious assault directly on Tanambogo shortly after dark on 7 August. Illuminated by fires started during a U.S. naval bombardment of the islet, the five landing craft carrying the Marines were hit by heavy fire as they approached the shore, with many of the US Navy boatcrews being killed or wounded, as well as heavily damaging three of the boats. Realizing the position was untenable, the Marine company commander ordered the remaining boats to depart with the wounded marines, and he and 12 men who had already landed sprinted across the causeway to cover on Gavutu. The Japanese on Tanambogo suffered 10 killed in the day’s fighting.

Throughout the night, as the Japanese staged isolated attacks on the marines on Gavutu under the concealment of heavy thunderstorms, Vandegrift prepared to send reinforcements to assist with the assault on Tanambogo. The 3rd Battalion 2nd Marines , still embarked on ships off Guadalcanal, was notified to prepare to assault Tanambogo on 8 August.

The 3rd Battalion US Marines began landing on Gavutu at 10:00 on 8 August and assisted in destroying the remaining Japanese defenses on that islet, which was completed by 12:00. Then the 3rd Battalion prepared to assault Tanambogo. The Marines on Gavutu provided covering fire for the attack. In preparation for the assault, U.S. carrier-based dive bombers and naval gunfire bombardment were requested. After the carrier aircraft twice accidentally dropped bombs on the U.S. Marines on Gavutu, killing four of them, further carrier aircraft support was canceled. US light cruiser USS San Juan, however, placed its shells on the correct island and shelled Tanambogo for 30 minutes. The Marine assault began at 16:15, both by landing craft and from across the causeway, and, with assistance from two Marine Stuart light tanks, began making headway against the Japanese defenses. One of the tanks got stuck on a stump. Isolated from its infantry support, it was surrounded by a group of about 50 Japanese airmen. The Japanese set fire to the tank, killing two of its crew and severely beat the other two crewmembers before most of them were killed by Marine rifle fire. The Marines later counted 42 Japanese bodies around the burned-out hulk of the tank, including the corpses of the Yokohama executive officer and several of the seaplane pilots. One of the Japanese survivors of the attack on the tank reported, “I recall seeing my officer, Lieutenant Commander Saburo Katsuta of the Yokohama Air Group, on top of the tank. This was the last time I saw him”. The overall commander of troops on Tanambogo was Captain (naval rank) Miyazaki-san who blew himself up inside his dugout on the late afternoon of 8 August.

Throughout the day, US Marines methodically dynamited the caves, destroying most of them by 21:00. The few surviving Japanese conducted isolated attacks throughout the night, with hand to hand engagements occurring. By noon on 9 August, all Japanese resistance on Tanambogo ended. In the battle for Gavutu and Tanambogo, 476 Japanese defenders and 70 U.S. Marines or naval personnel died. Of the 20 Japanese prisoners taken during the battle, most were not actually Japanese combatants but Korean laborers belonging to the Japanese construction unit.

Once again, the tenacity of the Japanese defenders shocked those who had to overcome it. ‘I have never heard or read of this kind of fighting’, 1st Marine Divisiıon commander Major-General Alexander A. Vandegrift wrote to the Marine Commandant in Washington, and he went on to explain: ‘These people refuse to surrender. The wounded will wait till men come up to examine them, and blow themselves and the other fellow to death with a hand grenade.’

On Rabaul at 8 a.m., the Japanese hurl 27 Betty bombers and 15 Zero fighters from Rabaul against US Task Force at Guadalcanal. The aircraft pass over Aravia, a small mountain village in northern Bougainville, where Coastwatcher Jack Read is huddled over his teleradio.

Read, 36, has been in New Guinea public service for 12 years, and Bougainville since November. He is glued to his set, fascinated with the American carrier jargon, when he hears the Japanese bombers fly over. He flashes “45 bombers now going southeast” to Turner, who gets the message at 10:40 a.m., and sounds general quarters.

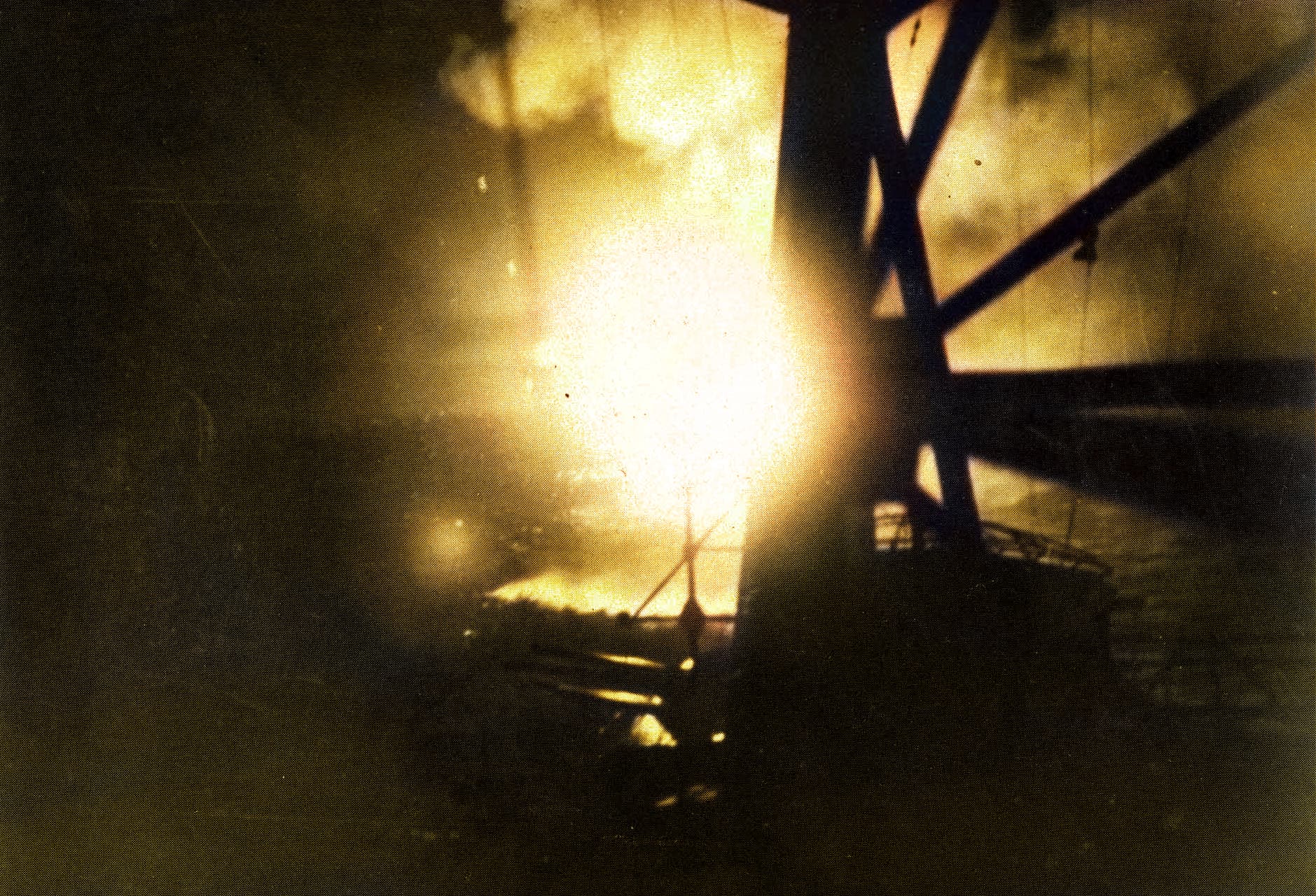

The Japanese avoid American F4Fs by a wide sing to the north and then a diving turn to emerge at treetop level over Florida island. 23 Bettys roar in, but heavy flak splashes one Zero and three Bettys. The bombers, following Organization No. 5, swoop in at 20 to 40 feet off the deck, fine against inaccurate Dutch anti-aircraft guns of January, but dangerous against radar- controlled 20mm guns of August. (HMS Prince of Wales had only seven when she was sunk, each transport at Guadalcanal alone has 12). Japanese planes, lacking armor and self-sealing fuel tanks, do flaming pinwheels into the sea. One Betty torpedoes US Navy destroyer USS Jarvis, killing 15, and another crashes into the transport George F. Elliot at 12:03. The transport erupts into flame, and the crew abandons ship. At least 17 die. The destroyer USS Ellet scuttles the transport later, but the burning hulk acts as a torch all day and all night. Only five of 23 Bettys stagger back to Rabaul. Two Zeros also fail to return. American air losses are nil.

Guadalcanal , South West Pacific : In the morning, seven Japanese cruisers and one Japanese destroyer under Admiral Gunichi Mikawa departed Kavieng, New Ireland and Rabaul, New Britain, sailing south without being detected; after sundown, the force caught the Allied warships by surprise off Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands; the Battle of Savo Island would result in the sinking of three US cruisers, one Australian cruiser, and one US destroyer , one of worst defeats in US Navy history.

Unprepared for the Allied landing operation at Guadalcanal, the initial Japanese response included airstrikes and an attempted reinforcement. Admiral Mikawa, commander of the newly formed Japanese Eighth Fleet headquartered at Rabaul, loaded 519 naval troops on two transports and sent them towards Guadalcanal on August 7. When the Japanese learned that Allied forces at Guadalcanal were stronger than originally reported, the transports were recalled.

Mikawa also assembled all the available warships in the area to attack the Allied forces at Guadalcanal. At Rabaul were the heavy cruiser Chōkai (Mikawa’s flagship), the light cruisers Tenryū and Yūbari and the destroyer Yūnagi. En route from Kavieng were four heavy cruisers of Cruiser Division 6 under Rear Admiral Aritomo Goto: Aoba, Furutaka, Kako, and Kinugasa.

The Japanese Navy had trained extensively in night-fighting tactics before the war, a fact of which the Allies were unaware. Mikawa hoped to engage the Allied naval forces off Guadalcanal and Tulagi on the night of August 8 and 9, when he could employ his night-battle expertise while avoiding attacks from Allied aircraft, which could not operate effectively at night. Mikawa’s warships rendezvoused at sea near Cape St. George in the evening of August 7 and then headed east-southeast.

The Japanese fleet was in fact sighted in St George Channel, where their column almost ran into American submarine USS S-38, lying in ambush. She was too close to fire torpedoes, but her captain, Lt Commander H.G. Munson, radioed: “Two destroyers and three larger ships of unknown type heading one four zero true at high speed eight miles west of Cape St George”: Once at Bougainville, Mikawa spread his ships out over a wide area to mask the composition of his force and launched four floatplanes from his cruisers to scout for Allied ships in the southern Solomons. At 10:20 and 11:10, his ships were spotted by Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Hudson recon aircraft based at Milne Bay in New Guinea. The first Hudson misidentified them as “three cruisers, three destroyers, and two seaplane tenders”. Some accounts state that the first Hudson’s crew identified the enemy ships correctly, but the composition of enemy forces was changed from the aircraft crews’ report by intelligence officers in Milne Bay.

The Hudson’s crew tried to report the sighting to the Allied radio station at Fall River, New Guinea. Receiving no acknowledgment, they returned to Milne Bay at 12:42 to ensure that the report was received as soon as possible. The second Hudson also failed to report its sighting by radio, but completed its patrol and landed at Milne Bay at 15:00. It reported sighting “two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and one unknown type”. For unknown reasons, these reports were not relayed to the Allied fleet off Guadalcanal until 18:45 and 21:30, respectively, on August 8.

Mikawa’s floatplanes returned around 12:00 and reported two groups of Allied ships, one off Guadalcanal and the other off Tulagi. By 13:00, he reassembled his warships and headed south through Bougainville Strait at 24 knots. At 13:45, the cruiser force was near Choiseul south-east of Bougainville. At that time, several surviving Japanese aircraft from the noon torpedo raid on the Allied ships off the coast of Guadalcanal flew over the cruisers on the way back to Rabaul and gave them waves of encouragement. Mikawa entered New Georgia Sound (later dubbed as “the Slot”) by 16:00 and began his run towards Guadalcanal. He communicated the following battle plan to his warships: “On the rush-in we will go from (south) of Savo Island and torpedo the enemy main force in front of Guadalcanal anchorage; after which we will turn toward the Tulagi forward area to shell and torpedo the enemy. We will then withdraw north of Savo Island.”

Mikawa heads on south. Aoba’s plane returns and reports two split Allied groups, north and south of Savo Island. At 16:42, Mikawa signals his battle plan. His force will penetrate the passage south of Savo in single line, torpedo the enemy units off Guadalcanal, sweep toward Tulagi to attack with gunfire and torpedoes, and withdraw by the passage north of Savo. Japanese task force will attack at 1:30 a.m. Banzai. At 6:30, all ships jettison topside flammables. 12 minutes later, Mikawa blinkers his ships, “In the finest tradition of the Imperial Navy we shall engage the enemy in night battle. Every man is expected to do his utmost.”

Mikawa’s run down the Slot was not detected by Allied forces. Admiral Kelly Turner commander of US Task Force and Landing Operations off Guadalcanal had requested that U.S. Admiral John S. McCain Sr., commander of Allied air forces for the South Pacific area, conduct extra reconnaissance missions over the Slot in the afternoon of August 8. But, for unexplained reasons, McCain did not order the missions, nor did he tell Turner that they were not carried out. Thus, Turner mistakenly believed that the Slot was under Allied observation throughout the day. However, McCain cannot totally bear fault, as his patrol craft were few in number, and operated over a vast area at the extreme limit of their endurance. Turner had fifteen scouting planes of the cruiser force, which were never used that afternoon and remained on the decks of their cruisers, filled with gasoline and serving as an explosive hazard to the cruisers.

To protect the unloading transports during the night, Australian admiral John Crutchley , commander of cruisers and other surface warships in Task Force , divided the Allied warship forces into three groups. A “southern” group, consisting of the Australian cruisers HMAS Australia and HMAS Canberra, cruiser USS Chicago, and destroyers USS Patterson and USS Bagley, patrolled between Lunga Point and Savo Island to block the entrance between Savo Island and Cape Esperance on Guadalcanal. A “northern” group, consisting of the cruisers USS Vincennes, USS Astoria and USS Quincy, and destroyers USS Helm and USS Wilson, conducted a box-shaped patrol between the Tulagi anchorage and Savo Island to defend the passage between Savo and Florida Islands. An “eastern” group consisting of the cruisers USS San Juan and HMAS Hobart and two U.S. destroyers guarded the eastern entrances to the sound between Florida and Guadalcanal Islands. Crutchley placed two radar-equipped U.S. destroyers to the west of Savo Island to provide early warning for any approaching Japanese ships. The destroyer USS Ralph Talbot patrolled the northern passage and the destroyer USS Blue patrolled the southern passage, with a gap of 7.5 - 12 miles between their uncoordinated patrol patterns. At this time, the Allies were unaware of all of the limitations of their primitive ship-borne radars, such as the effectiveness of the radar could be greatly degraded by the presence of nearby landmasses. USS Chicago’s Captain Bode ordered his ship’s radar to be used only intermittently due to the concern it would reveal his position, a decision that conformed with general navy radar usage guidelines, but which may have been incorrect in this specific circumstance. He allowed a single sweep every half hour with the fire control radar, but the timing of the last pre-engagement sweep was too early to detect the approaching Japanese cruisers. Wary of the potential threat from Japanese submarines to the transport ships, Crutchley placed his remaining seven destroyers as close-in protection around the two transport anchorages.

The crews of the Allied ships were fatigued after two days of constant alert and action in supporting the landings. Also, the weather was extremely hot and humid, inducing further fatigue and, inviting weary sailors to slackness. In response, most of Crutchley’s warships went to Condition II the night of August 8, which meant that half the crews were on duty while the other half rested, either in their bunks or near their battle stations.

In the evening, Admiral Turner called a conference on his command ship off Guadalcanal with Admiral Crutchley and Marine division commander Major General Alexander A. Vandegrift to discuss the departure of Admiral Fletcher’s carriers (Fletcher was anxious to pull his cariers from shalllow shore of Solomons which was way close to Japanese air and naval bases in New Britain and his carriers were low on fuel on 8th August. As a result of the loss of carrier-based air cover, Turner decided to withdraw his ships from Guadalcanal, even though less than half of the supplies and heavy equipment needed by the troops ashore had been unloaded. Turner planned, however, to unload as many supplies as possible on Guadalcanal and Tulagi throughout the night of 8 August and then depart with his ships early on 9 August) and the resulting withdrawal schedule for the transport ships. At 20:55, Crutchley left the southern group in light cruiser HMAS Australia to attend the conference, leaving Captain Howard Bode of USS Chicago in charge of the southern group. Crutchley did not inform the commanders of the other cruiser groups of his absence, contributing further to the dissolution of command arrangements. Bode, awakened from sleep in his cabin, decided not to place his ship in the lead of the southern group of ships, the customary place for the senior ship and went back to sleep. At the conference, Turner, Crutchley, and Vandegrift discussed the reports of the “seaplane tender” force reported by the Australian Hudson crew earlier that day. They decided it would not be a threat that night, because seaplane tenders did not normally engage in a surface action. Vandegrift said that he would need to inspect the transport unloading situation at Tulagi before recommending a withdrawal time for the transport ships, and he departed at midnight to conduct the inspection. Crutchley elected not to return with HMAS Australia to the southern force but instead stationed his ship just outside the Guadalcanal transport anchorage, without informing the other Allied ship commanders of his intentions or location.

As Mikawa’s force neared the Guadalcanal area, the Japanese ships launched three floatplanes for one final reconnaissance of the Allied ships, and to provide illumination by dropping flares during the upcoming battle. Although several of the Allied ships heard and/or observed one or more of these floatplanes, starting at 23:45 on August 8, none of them interpreted the presence of unknown aircraft in the area as an actionable threat, and no one reported the sightings to Crutchley or Turner.

Mikawa’s force approached in a single 3-kilometer (1.9 mi) column led by Chōkai, with Aoba, Kako, Kinugasa, Furutaka, Tenryū, Yūbari, and Yūnagi following. Sometime between 00:44 and 00:54 on August 9, lookouts in Mikawa’s ships spotted Blue about 9 kilometers (5.6 mi) ahead of the Japanese column.

South West Pacific : American submarine USS S-38 torpedoed and sank Japanese troop transport Meiyo Maru (which was bringing reinforcements but turned back after scale of US landings bwcame clear to Japanese) 14 miles west of Cape Saint George, New Ireland at 2000 hours; 353 Japanese naval troops aboard were killed.

Pacific Ocean : American submarine USS Silversides torpedoed and sank Japanese freighter Nikkei Maru off southern Honshu island, Japan.

American submarine USS Narhwal torpedoed and sank Japanese cargo ship Bifuku Maru off Kuril Islands