Summary of Robert Gerwarth’s The Vanquished: Why the First World War Failed to End, 1917–1923 . Epilogue: The “Post-War” and Europe’s Mid-Century Crisis. Penguin Random House. 2016. ISBN 9781846148118.

“ On March 23, 1919, we raised the black flag of the fascist revolution, the precursor of the European renewal. Veterans of the trenches and young men rallied around the flag creating groups willing to fight against coward governments and fatal eastern ideologies, to liberate the peoples from the negative influence of 1789. Thousand comrades have fallen around this flag fighting as heroes, with the most substantial meaning of the Roman word, on the streets and the plazas, in Africa and in Spain. Their memory is always alive and present in our hearts. Maybe some have forgotten the hardships of the post-war years [a guy from the crowd shouts “ Nobody! ”] , but the squadristi did not forgot them, they can’t forget them [a guy from the crowd shouts “ Never! ”].

Mussolini’s speech in 1939, for the 20th anniversary of the foundation of the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento.

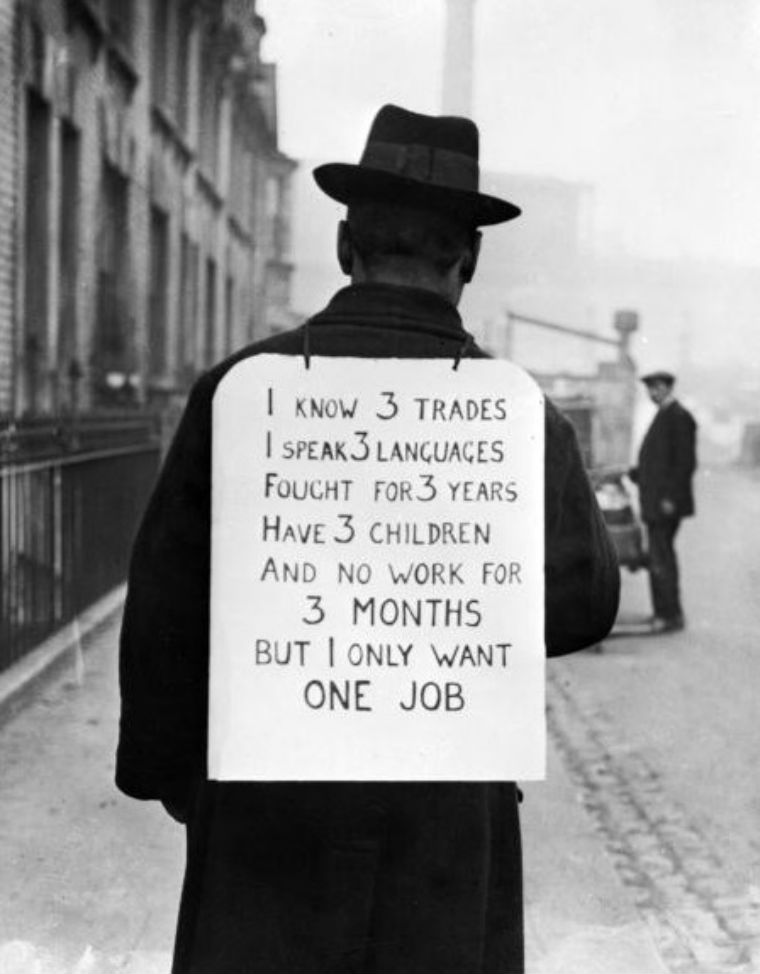

Fascism wasn’t created by the Great Depression, but it was strengthened by it. Fascism was conceived amidst the violence of World War I and was born during the tumultuous time immediately after the Armistice. The peoples lost their faith in Democracy and economic liberalism, as both proved unable to solve their problems, mainly the unemployment, and turned to the extreme political spectrum, Right and Left. At this time, it seemed fitting to many conservatives, just as in Italian case in 1922, that the Nazis were an alternative against the communists.

Before 1914, the European states were proud of themselves about the level of security they provided to their citizens, and even during WW1 they kept the monopoly of violence. The violent legacy of the Great War’s aftermath, was that the states lost that monopoly, starting from the October Revolution. Soon enough, the “internal enemies” were not portrayed as humans, and thus they did not deserved mercy. The majority of the killed during inter-war were civilians. The Right believed that only the removal, by every mean, of all “foreign elements” or all who “were preventing the balance in society”, would create a strong and ethnic “pure” nation. Hitler believed that the German Empire failed to “civilize” and subjugate Eastern Europe because she didn’t used enough means before and during WW1. This goal could succeed only with a total war, against the “internal enemies” as well, not just the external ones. On the other side, the extreme Left believed in class struggle, in the armed revolution and not the parliament, and the elimination of class enemies. Events like the Nazi purges, the Stalinist purges, and the coining of terms like “The 5th Column” were realizing this particular spirit.

From the end of WW1, a culture of violence as a mean to the political ends was established in most parts of Europe. From the Freikorps in Germany to the SA, the Hungarian Arrow Cross, the Austrian Heimwehr, the Croatian Ustashe and the Patriotic Guards in the Baltics, the Lithuanian Riflemens’ Union, the Latvian Aizargi and the Estonian Kaitseliit, all devoted themselves against the spread of communism, in general, and the paramilitary units of the European communist parties in particular, guided by the Comintern and aiming the international revolution. In Bulgaria, the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (active since 1893), which aimed the creation of a Bulgarian autonomous state in the region of Macedonia, was strengthened after its role in the 1923 coup and murder against prime minister Aleksandar Stamboliyski, it became a state within the state and, until 1934, carried out over 460 armed operations in Yugoslavian territory (assassinations, kidnappings etc.). IMRO actions in Greek territory resulted in a short Greco-Bulgarian war in 1925.

In Portugal, the Ditadura National was established by a coup in 1926, and the country remained under dictatorial regime until 1974. In Spain, the coup of general Miguel Primo de Rivera established a fascist-inspired dictatorship, with the support of the king, from 1923 until 1930. His inept leadership and his regime discredited the monarchy and alienated the armed forces, so the king called for elections in 1931, and when the republicans won, the king abdicated, and a republic was proclaimed. The new republic was hit by the Great Depression and the high tensions between the Republicans and the Right, both of them radicalized. Especially the new Constitution which instituted secularization along with anti-clerical violence of extreme Leftists, pushed the conservatives to hardline political views. In response, the Left, seeing that the landowners and the armed forces challenged the new regime, moved to more extreme views as well. In 1936, when the Popular Front (the coalition between Socialists and Communists) narrowly won the elections and subsequently formed a minority government, the armed forces responded by a coup which immediately evolved into a full-scale civil war.

Almost every prominent figure in the new regimes of the 30’s recognized his “political awakening” in the period of 1918-1923, and most of them took part in the violent events. Later, when they rose to power, they believed that it was time to settle the old scores. Men like Himmler, Reinhard Heydrich, Rudolf Höss, Robert Ritter von Greim, Hans Albin Rauter were members of Freikorps units. The White Terror in Hungary during 1920-21, apart antisemitic pogroms, produced the leaders of the Hungarian National Fascist Party in 1932 and the same men in 1944 fought the Soviets in Budapest along the Nazis, like Pál Prónay and Ferenc Szálasi. The traditional Austrian antisemitism ant Slavophobia was further enhanced by the mass migration of Jews from the former Austro-Hungarian provinces to Vienna, after the war and resurfaced after the Great Depression.

The Treaty of Lausanne, the reversal of a WW1 treaty, the conversion of a defeated side to a victorious one, the expulsion of minorities and the creation of a new homogeneous, secular nation, impressed Mussolini and Hitler, who found a role model on Mustafa Kemal’s successful military action against the Entente. In Hungary and Bulgaria, where the loss of territory and population from the Great War’s peace treaties was grave, the revision of the post-war status quo was still very popular. Japan, deeply insulted by the USA and the British dominions, which blocked the stipulation about racial equality in the Covenant of the League of Nations, and pressed by Japanese military and industrial circles (the latter known as “zaibatsu”), which demanded an imperial expansion to acquire raw materials that Japan lacked, became an ultra-nationalist totalitarian state, that shared many commons with the fascist states, such as the hatred towards communism and liberal economy.

In many countries, the anticapitalistic and anti-parliamentary spirit was realized in authoritarian and ultra-Right regimes, in the pretext of re-establishing “stability” and “order”. In Bulgaria, Zveno, a political/military organization, having links to the coup that overthrew and killed prime minister Aleksandar Stamboliyski in 1923, came to power after a successful coup in 1934, dissolved all political parties and trade unions and introduced a corporatism similar to that of fascist Italy. In less than a year, they were overthrown by a coup organized from king Boris III, who established his own regime, despite the presence of Parliament and political parties. In neighboring Yugoslavia, struggling between the centralization of the government, the Serbian supremacy, and the desire of the constituent nations for more autonomy, king Alexander suspended the constitution and established his dictatorship in 1929, after the assassination of five Croats MPs. Eventually he was assassinated in Marseille by the joint effort of Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization, and the Ustashe, an organization aiming the creation of an independent Croatia. In Poland, General Józef Piłsudski, carried out a successful coup in 1926 and stayed in power until his death in 1935. Although Poland never became a fascist/dictatorial country, the new regime was far more authoritarian than before 1926. A similar path was followed by Estonia and Latvia in 1934.

In Austria, prime minister Engelbert Dollfuss, in a midst of an economic crisis, the closing of Creditanstalt Bank (the largest bank of Austria) and clashes between the paramilitary organizations of the political parties, shut down the Parliament, persecuted socialists and Austrian Nazis and established himself as a fascist dictator. In 1934 he was assassinated in a failed coup attempt by the Nazis and his successor, Kurt Schuschnigg, continued to rule Austria by degrees until the Anschluss.