Brooklyn Eagle (September 9, 1942)

U.S. TRANSPORT SWEPT BY FIRE; 1,590 SAVED

Ex-luxury liner’s hulk is towed in

Warships rescue women, children on the Wakefield – crewmen burned

By Walter Cronkite, United Press Atlantic Fleet correspondent

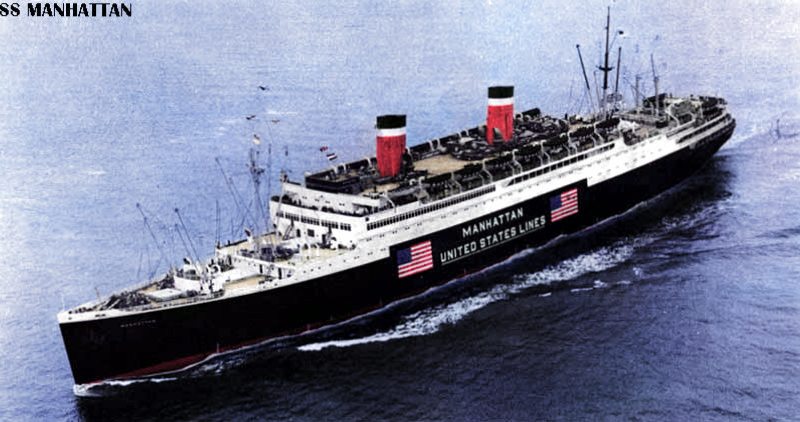

The 24,289-ton liner Manhattan. Renamed the Wakefield and taken over by the Navy as a transport, she caught fire while on way to East Coast port with 1,600 passengers, including women and children stranded ion British Isles and Éire. All were saved unharmed, but several crew members were seriously burned.

Aboard a U.S. warship on Atlantic convoy – (Sept. 3, delayed)

The 24,289-ton U.S. Navy transport Wakefield, formerly the American luxury liner Manhattan, burned within sight of this ship tonight and was abandoned on the Atlantic after her crew and 840 passengers were rescued by escort vessels.

A few hours later, the Wakefield was reboarded by a skeleton crew and the hulk was towed into an American East Coast port.

The Wakefield ’s passengers included American women and children who had been stranded in the British Isles and Éire since war began, construction workers who had been building American Army facilities in Britain and some United States Army officers returning to the United States for advanced technical training or to act as instructors.

None of the passengers was injured but several of the 750 crew members were burned, two seriously.

I could see the rescue vessels crowd so close to the burning ship that their paint was scorched and their hulls bruised as they bounced against the Wakefield to take off the passengers by means of rope ladders and improvised gangways.

Flames were discovered pouring from a passenger’s cabin shortly after 6 p.m. and soon were racing down the corridors of B deck. They defied control and two hours to the minute later, the skipper, Cdr. Harold G. Bradbury, United States Coast Guard, ordered her abandonment by the crew members who had risked entrapment to stay aboard and fight the flames.

Cause of the fire either was not determined immediately or could not be disclosed pending official investigation. Preliminary reports indicated that a passenger’s carelessness, perhaps in the handling of a cigarette, was to blame.

The Wakefield and her sister ship, the former Washington, were the second largest passenger ships in the American Merchant Marine and among the newest. The Wakefield was launched in 1932. Of American-built ships, only the America – now named the West Point – was larger.

Was in troop convoy

The Wakefield was in this convoy returning to the United States after a successful and uneventful crossing with the largest number of troops ever ferried over the Atlantic in a single operation.

Had she been alone and unescorted, the flames might have taken a heavy toll of lives. But a cruiser and two destroyers of the convoy escort were alongside the Wakefield within 10 minutes after she broke radio silence to message:

Am on fire.

The rescue operation also was favored by a glassy sea and a clear sky.

Favored by calm sea

Capt. C. F. Bryant, commander of the convoy escort, said:

If it had been a bad night with a rough sea, we couldn’t have taken off one-tenth of those people, not one-tenth.

Taken aboard one destroyer were 228 persons and most of the remainder were taken into the cruiser. The rescued so crowded the fighting ships that they were forced to sleep on deck under the few blankets and extra clothes available. Few of the rescued were able to save their luggage and possessions.

Reluctant to give up ship

Commanders of the rescue vessels pleaded with Bradbury to abandon his ship for an hour before he finally admitted that the fire couldn’t be controlled. Those of his crew who desired were rescued early, but most of them chose to remain with the captain in the losing fight.

Disaster struck quickly as this convoy neared the port from which it had departed a month ago and as the officers and members of the crew were congratulating themselves on a crossing with perfect weather and a complete absence of enemy interference.

It struck in full view of returning American nationals on other ships of the convoy.

Reporter views blaze

Through the binoculars from this ship, just 1,000 yards away, could be seen the Wakefield crew running forward to their fire stations.

Within ten minutes, the Wakefield was shrouded in smoke.

The first message of important from one of the destroyers came:

Have taken off all except those of the crew that wish to keep aboard.

It was followed later by another:

There is a nucleus of a crew still aboard. The engines are still okay and they think they can bring her [the Wakefield] on in.

Fifteen minutes later, still reflecting Bradbury’s confidence that he could save his ship, came a message from the cruiser:

The captain has asked us to push off. I estimate that 300 to 400 crew members are still on board manning the hoses. The captain hopes to be able to get the ship into port.

But 10 minutes later, her captain was back on the radio. He said:

The fire seems to have broken out with new intensity. We had better stand by again.

One of the destroyers has shoved off but we are still alongside. We are riding easily but losing a little of our paintwork.

At 7:55 p.m., the cruiser commander messaged:

The fire apparently is out of control.

There followed a long silence until at 8:20 the cruiser captain was back with:

They are now abandoning ship and coming aboard.

Crew stands by

Many of the crew members stayed aboard until it no longer was possible for the rescue ships to maneuver alongside.

Later, when the intensity of the fire had abated somewhat, Bradbury led a special firefighting party back aboard the Wakefield and they then succeeded in getting the flames under control, the Navy said.

Tugs and salvage craft were summoned and they safely towed the bulk of the ship to an Atlantic port.