Eisenhower had visited Monty for the first time in North Africa on 31 March and had ‘a most interesting time’ being given a tour of the Mareth Line before all the debris of battle had been towed away. He was not much taken with the Eighth Army commander, however. ‘He (Montgomery) is unquestionably very able, but very conceited,’ Ike wrote to Marshall. ‘He is so proud of his successes to date that he will never willingly make a single move until he is absolutely certain of success.’ This was true. Although he had very good reasons for assuringf success before starting any operation , like rigid order based operational mentaility of British Commonwealth forces and dimishing manpower and replacements , Monty had been also irascible and had rubbed people up the wrong way long before he ever reached North Africa, but if his ego had reached new levels after Alamein, it was now out of control in the wake of his Mareth victory. His belief in his own pre-eminence was total. ‘I like Eisenhower,’ he told Alex. ‘But I could not stand him about the place for long; his high-pitched accent, and loud talking, would drive me mad. I should say he was good probably on the political line; but he obviously knows nothing about fighting.’ Ike did not speak with a high-pitched accent; his voice was strong and quite deep. Monty, however, did, and was notorious for it. Nor was he in any real position to make judgements about Ike’s capabilities; rather, his assessment was suspiciously similar to Brooke’s.

In his letters and notes, Monty wrote as though his authority was absolute, no matter to whom he was writing. Eighth Army was always ‘his’. References were always made to ‘my’ artillery, ‘my’ tanks; ‘I’ have given Rommel a bloody nose. His notes to Alex were frequently bossy and dictatorial in tone. ‘It is vital to keep the Americans on their side of the agreed boundary,’ he wrote on 8 April. ‘Please impress this on the Americans, French, and everyone else. Keep clear of my area.’ Alex was used to this. He knew Monty would never change and he took no notice of his tone. If he agreed with Monty, he acted upon his suggestions; if he did not, he ignored them.

Alex could do this because he was Monty’s commanding officer. But his corps commanders could not. Lumsden had ‘bellyached’ (disagreed with him) and had been sacked after Alamein. Horrocks and Leese were his lieutenants, men who carried out his wishes without question. This was fine so long as any plan was Monty’s and so long as he kept firm control and command at all times. The problem during the drive through the Tebaga Gap had been that Monty had not been commanding the left hook of the battle. He had been some way from the main action and had left the drive through to El Hamma to Horrocks, and Horrocks lacked the confidence and strength of character to take potentially risky or costly decisions. Monty’s mantra of proceeding only when victory was guaranteed had rubbed off too strongly; his autocratic style of command hindered initiative.

The same was now true at Wadi Akarit. Monty had left the running of the battle largely to Leese and Horrocks, and once again Horrocks dithered. Not until 1 p.m. did the first tanks of 8th Armoured Brigade start nosing across the 4th Indians’ anti-tank ditch, some four and a quarter hours after Tuker had told Horrocks the coast was clear. The Sherwood Rangers had been formed up and ready to move much earlier in the morning, when they were bombed by their own side – though casualties were light. Stanley Christopherson was told that they were being held up by strong anti-tank fire at the end of the pass. This was true. German anti-tank guns were lurking at the far end of the valley behind the Djebel Roumana, but, as Tuker was quick to point out, these were comparatively few in number and no match for the hundreds of tanks and guns available to 10th Corps and the New Zealanders, who had been placed temporarily under 10th Corp’s command. At 9.20 a.m. Tuker had even sent his trucks over the anti-tank ditch to resupply his forward infantry – and they had done so without so much as a scratch. At regular intervals, Tuker sent through increasingly ‘peevish’ enquiries as to why on earth 10th Corps wasn’t pushing through, until, at 4 p.m., he was told 10th Corps was now going to wait until dawn the following morning, moving behind another massive air bombardment and barrage. Tuker was appalled. His men had done all the hard work and 10th Corps had been handed the battle on a plate. That Horrocks was prepared to squander it so feebly beggared belief.

Meanwhile, to the right, the Highlanders were facing vicious counter-attacks. Bitter fighting continued all day and into the evening along the ridge and the wadis below it, fighting that could have been largely avoided had 10th Corps pushed through. Johnny Bain had remained in his hole for much of the day, occasionally seeing figures moving about in stick-like clusters. As usual, no one along their line was really sure what was going on. Johnny watched and waited in a state of trance-like indifference, something he’d noticed would come over him whenever he was close to the action. By nightfall, the fighting seemed to die down.

Throughout the afternoon, Nainabahadur Pun and the men of 1/2nd Gurkhas had fought off repeated efforts by the Germans to retake the Fatnassa Hills; they were now holding a 3000-yard mountainous front. The enemy had made no progress, however, and at the end of the day the entire division had lost only around 400 men. Whilst this had been going on, the Axis commanders had been discussing their options. Messe believed they could hang on, but von Arnim was more pessimistic. In the end, it was the commanders of the 15th Panzer and 90th German Light Divisions who had the casting vote, and they believed they should retreat overnight or face annihilation. “That was NOT a good battle for us” commanted Messe.

During the early hours, the air and artillery bombardment began, but on empty Axis positions. At 7 a.m. on 7 April, 10th Corps finally passed through 4th Indian’s and 50th Division’s fronts. Once again, Eighth Army had won the battle but failed to finish the job. ‘Here, in this spot,’ wrote Tuker, ‘the whole of Rommel’s army should have been destroyed and Tunis should have been ours for the taking. Again the final opportunity and the fruits of our victory have been lost.’ But Tuker despite all his brilliance , overstates his version. The past engagements when British armor charged enemy anti tank screen rarely ended well for Britisk armor and even when suceeded overwhelming enmy gun screens , the tank casaulties had been devestating. No one in 10th Corps wished to participate another Supercharge style unsupported tank charge like happened in Tel El Aquaqir and Rahman track and be one of the last casaulties when the end of victorious campaign had been in sight. So in that sense Horrock’s decision had been the correct one. Eventually it was the Germans and Italians who blinked the first and retreated to Enfidaville after Eighth Army captured Wadi Akarit heights and repulsed all Axis counter attacks to recapture them.

That morning, Johnny Bain and the Gordon Highlanders had crept up over the Djebel Roumana, unsure at that stage whether the enemy was still there or not. The dead were scattered across the hillside. Johnny stumbled by a lifeless Seaforth Highlander. ‘There’s one poor bastard’s finished with fuckin’-an’-fightin’,’ said his friend. ‘Already the flesh of the dead soldiers, British and enemy, was assuming a waxy theatrical look,’ wrote Johnny, ‘transformed by the maquillage of dust and sand and the sly beginnings of decay.’ Then men in his own section started bending over the bodies, turning them over with their boots and taking watches, rings and any other valuables they could find.

Johnny watched this for a moment, then simply turned away and began walking back down the hill. No one stopped him, and he later picked up a ride all the way back to Tripoli. On the Djebel Roumana, Johnny had realized he’d had enough of fighting. And so he deserted. (later he was pardoned and joined Normandy Campaign in 51st Highland Division in 1944)

Alan Moorehead had been having a busy time, flitting from one part of the front to the other, but on 7 April he was near Medjez el Bab, where 78th British Division was beginning another assault. He had noticed that in the past couple of weeks the efforts of the Luftwaffe had been considerably on the wane; he’d barely seen a Stuka for days. But as he and a fellow reporter drove towards Testour, ten miles south-west of Medjez, yellow tracer bullets suddenly began spitting either side of them. The driver immediately slammed on the brakes, skidded to a halt, and they all leapt out as a Grman Me 109 fighter roared past only twenty feet over their heads. At the same time, a nearby Bofors crew opened fire, hitting the Messerschmitt on its underside. Alan watched as it flew on, rose slightly, then banked, before belly-landing in a field of wild flowers.

They rushed towards the aircraft, but the Arabs had got there first. The pilot had made an attempt to get away and hide, but was quickly found and marched back to his machine with his hands behind his head and a pistol pressed into his back. ‘He was a strikingly good-looking boy,’ wrote Alan, ‘not more than twenty-three or four, with fair hair and clear blue eyes.’ He was searched and his pistol taken from him then everyone stood back. The pilot looked suddenly alarmed. ‘He stiffened and the hand holding the cigarette was tensed and shivering,’ noted Alan, who had realized that the pilot thought he was about to be shot. ‘Little globes of sweat came out in a line on his forehead and he looked straight ahead.’

But he was not executed of course, nor was he ever going to be. Someone moved towards him, and motioned the pilot to come with him. The relief on his face was unmistakable. But for Alan it had been an illuminating experience. ‘This actual physical contact with the pilot,’ he wrote, ‘his shock and fear, suddenly made one conscious that we were fighting human beings and not just machines and hilltops and guns … But now, having captured a human being from that dark continent which was the enemy’s line, one wanted to talk to the pilot and argue with him and tell him he was wrong.’

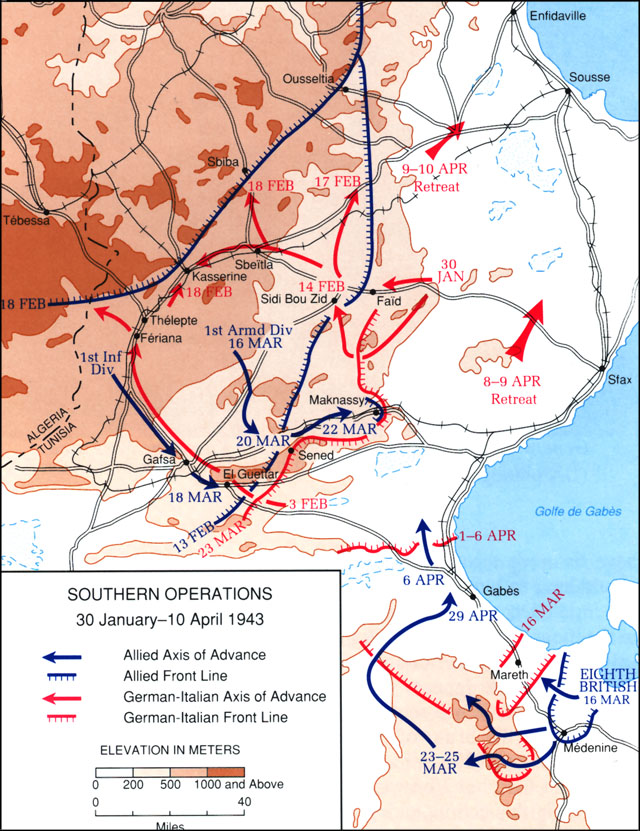

Air reconnaissance and intelligence soon showed that the Axis were pulling out of the El Guettar massif and Maknassy areas as well. That same day, 7 April, 2nd US Corps finally linked up with Eighth Army on the Gafsa-Gabès road. Alex had anticipated such a retreat and on 4 April had ordered another attack through the Fondouk Pass. He now had General Crocker’s British 9th Corps in Tunisia, and since the 34th US Red Bull Division was already to the west of the pass it made sense to use both forces together, with Ryder’s men temporarily under Crocker’s command.

Crocker’s background was with tanks rather than infantry: the 6th Armoured Division – of which the Guards Brigade was the mobile infantry – was the backbone of his corps. Doc Ryder’s men had had the least combat experience of all 2nd US Corps forces, while the British 128th Brigade that was loaned to Crocker had to be brought out of training at 18th Army Group’s battle school early, but Alex hoped that overwhelming strength would see them through. Unfortunately, however, Crocker’s plan was faulty, largely because he ignored Tuker’s tenet that the highest ground needs to be captured first. The attack was actually to be made through two passes: the Pichon north of the Djebel Rhorab, the Fondouk to the south. This high ground in the centre thus dominated the position, but although it was to be shelled, it was not on Crocker’s list of objectives. General Ryder, whose men were to pass to the south of the Djebel Rhorab, was not happy about this, and so gained permission to start his attack early in the morning of 8 April, and under the cover of darkness.Sergeant Bucky Walters in 1st Battalion, 135th Infantry, was once again in reserve, following on behind the 3rd Battalion, who were to lead the assault against the high ground to the south of the Fondouk Pass. To their right was the 133rd Battalion, but from the outset their attack was mired in confusion. Rather than begin their attack at 3 a.m., as planned, they finally got going some two hours later. At 6.30 a.m., the leading troops gave the signal that the artillery barrage should start. A number of the shells fell short, hitting their own men, but the Red Bulls pressed on. By now the Axis troops in the hills above them were fully awake to the attack and began finding their range on the advancing troops with ease. At 7.30 a.m., the American advance was halted entirely; an air bombardment was due to start half an hour later and the infantry was concerned not to be within the 2000-yard bomb line previously agreed. Unbeknown to them, however, corps HQ had already cancelled the air attack precisely because it was worried the Red Bulls had already advanced too far.

All this time, the poor infantry were milling around, wondering what was going on and offering themselves as sitting ducks. Another artillery barrage began at 9.30 a.m., but by this time it was too late. It was now broad daylight, and the Americans were coming under heavy attack. Bucky had not been far behind the assault troops. ‘Our advance was delayed once, then twice then three times,’ he says. ‘We could feel that somebody who was issuing orders wasn’t doing their job properly.’ All he could see was a number of hillocks from which enemy fire was pouring down among them. ‘We were right in front of them in open skirmish order. It was like World War I.’ Then they reached the enemy minefields. Bucky’s lieutenant trod on a mine nearby. ‘I saw him go,’ says Bucky, who by now hadn’t the faintest idea what they should be doing and what the hell was going on. The advance ground to a halt and the Red Bulls began hastily digging foxholes. ‘It was pretty flat as we advanced,’ says Bucky. ‘We’d have been entirely wiped out if we’d gone any further. It was murderous and a terrible, terrible piece of strategy.’

However, 128th British Brigade had had an easier time. Their advance had begun on time and their objectives, against weak opposition, had been taken. By late afternoon they had turned south with a view to taking Djebel Rhorab. But with the Red Bulls’ attack grinding to a halt, Crocker ordered his tanks of the 6th Armoured Brigade to go and help the Americans. They arrived just as 34th US Division’s own armour was renewing their attack. More confusion followed, but later the Red Bulls’ armour made another attempt at an advance. Reaching the foot of the massif ahead of them, they were shot to pieces by 88s. They were short of leadership, not courage.

Overnight, Alex ordered Crocker to send in 6th British Armoured Division in force and to smash through the pass whatever the cost. The Americans also launched another attack, and this time Bucky Walters was in the main assault, accompanied by a tank-destroyer battalion. ‘Men were getting hit by small arms and shrapnel,’ says Bucky. ‘The enemy was firing air bursts – they were terrible.’ Time and again, Bucky and his men hit the dirt, before eventually crawling to a hillock and finding some disused foxholes. There he watched one tank after another get hit. ‘They were coffins,’ says Bucky. ‘The 88s were devastating.’ At one point he looked down into his foxhole and saw an ant and wished he could be the same size.

The Djebel Rhorab was eventually taken at great cost by the Welsh Guards later that afternoon. Watching them from the high ground facing the pass was Captain Nigel Nicolson, who was amazed to see them advance in long lines over open ground, crouching down as they ran forward. ‘In the closing stages of the infantry attack, I suddenly observed fifty of the enemy rise from their trenches, throw down their arms, and advance down the hill with their hands up, led by their officer,’ he later wrote to his parents. Meanwhile, to the south, 6th British Armoured Division had launched their assault. Many of the tank crews had assumed it would be their last day – the odds of surviving the enemy guns seemed so slim. But they’d set off all the same, their spearhead led by a young squadron leader of the 16/15th Lancers. Moving in a wide, open formation they pushed forward, shellfire soon whistling around them. ‘There’s a hell of a minefield in front,’ reported the squadron leader. ‘It looks about three hundred yards deep. Shall I go on?’

‘Go on,’ came the reply. ‘Go on at all costs.’

They did so, losing twenty-seven tanks in the process. The squadron leader was killed, but it could have been very much worse. As darkness fell, however, they stopped, because word had arrived that 10th and 15th Panzer Divisions were moving up. This was not the case; what had been spotted was the flank guard protecting the Panzer divisions as they continued their escape northwards. The following morning, 6th Armoured Division pushed through into the plains, and the Red Bulls finally captured the high ground to the south of the pass. But by then, the Axis had largely evaded the Allies once again.

Bucky Walters felt deeply dispirited. The division had lost nearly 800 men, but he felt they’d performed badly and let everyone down. ‘We had some good officers, and some good men,’ he says, ‘but at that time we weren’t that battle-wise and our chain of command had broken down somewhere … Our officers were brave men, but they didn’t have the experience to keep us moving.’ In contrast with Colonel John Forst, Bucky also felt that they suffered by not feeling any hatred towards the enemy. ‘We didn’t hate them because before Fondouk we hadn’t seen too many of our men being mangled and killed by them. Now, when you see your buddies being killed, a sense of anger develops, and anger gives you a kind of impetus to start hating the enemy, and once you have that you start becoming a better soldier.’

This was a sentiment that Alex certainly agreed with, as did Patton, but although the Red Bulls’ failure at Fondouk was as much to do with Crocker as it was Ryder, this joint operation caused Patton to explode with indignation, especially when word reached him that the British press had been particularly critical of Doc Ryder’s men. ‘God damn all British and all so-called Americans who have their legs pulled by them,’ he wrote, then confided to his diary: ‘I feel all the time that there must be a showdown [with the British] and that I may be one of their victims. Ike is more British than the British and is putty in their hands.’

This was written in private and when his blood was up: Patton was always a highly emotional man. Like most people, he resented criticism of his own people; but, despite this, his view of much of 2nd US Corps was extremely similar to that of Alex. The problem was that Alex tended to tar them all with the same brush, which was harsh on the Rangers, who were now a class act, and also the Big Red One, which was developing into a fine infantry outfit. Nonetheless, both agreed that all too often the Americans had lacked ‘drive’. In his report on 2nd US Corps’ recent operations, Alex concluded: ‘34 Div would have captured the high ground south of Fondouk if they had gone all out at the first attempt.’

This was a criticism Patton frequently directed at 1st US Armored Division. ‘I have little confidence in Ward or in the 1st Armored Division,’ he noted on 28 March. ‘The division has lost its nerve and is jumpy.’ The very next day, Alex echoed these sentiments in a letter to Monty. ‘The trouble, as I have said, is with the troops on the ground who are mentally and physically rather soft and very green. It’s the old story again – lack of proper training allied to no experience of war.’

Two days after that, with 2nd US Corps unable to force a breakthrough along the El Guettar massif, Patton recorded: ‘Our people, especially the 1st Armored Division, don’t want to fight – it is disgusting.’ Alex’s report also concluded that there was ‘at present a lack of confidence in their officers by the ORs because they feel they don’t know their job. This, of course, affects discipline.’ Again, this was a concern Patton felt too. Larry Kuter had met up with Patton just after Fondouk. ‘He said that he had lost 286 junior officers because most of them had to do the work that sergeants and corporals should have been trained to do,’ recorded Larry. ‘He concluded tearfully, “I still couldn’t make the sons of bitches fight.”’

On 2 April, Alex had written to Patton suggesting Ward be replaced. Although Patton did not know it at the time, Alex had done so only at Eisenhower’s insistence. Patton was in agreement, although resented Alex’s involvement. ‘I should have relieved him on the 22nd or 23rd [March],’ noted Patton, ‘but did not do so because I hate to change leaders in battle, but a new leader is better than a timid one.’ By now, however, Patton was already in a thoroughly bad mood, frustrated by British interference and annoyed that Eighth Army was getting all the glory while his 2nd US Corps had been given little thanks for holding off 10th Panzer Division that would otherwise have been confronting Monty’s men.

He was particularly annoyed that Eighth Army seemed to be getting the lion’s share of the air support available. Matters came to a head on 1 April, when some German aircraft attacked one of Patton’s observation posts, killing three men, including his ADC, of whom he was particularly fond. As Patton later admitted, this radio post had not been regularly moved (US Armyt wireless security remained very klax till the end of war) , enabling the Germans to get a fix on it. But that evening, through grief, anger and mounting frustration, he added to his daily sitrep, ‘Forward troops have been continuously bombed all morning. Total lack of air cover for our units has allowed German air forces to operate almost at will,’ and then sent it off with a much wider distribution than normal.

Larry Kuter saw the sitrep that night at Ain Beida, but thought little of it, thinking it so obviously exaggerated and emotional that no one would pay it the slightest bit of attention. The following morning, however, he got another surprise. Mary Coningham had read Patton’s complaint, had become increasingly incensed, had written a detailed response and had sent it to everyone who received the original message :

"Total enemy effort over 2 CORPS GUETTAR Front. 0730 unspecified number of fighters. 0950. 12 Ju87s. 1000. 5 Ju88s and 12 ME 109s of which some bombed. Total casualties four killed, very small number wounded. Our effort up to 1200 hours. 92 Fighters over 2 CORPS front. 96 Fighters and Bombers on enemy aerodromes concerned. On SFAX, 90 Bombers at 0900. For full day, 362 Fighters, of which 260 over 2 CORPS.

Mary then finished by adding, ‘12th AIR SUPPORT COMMAND have been instructed not to allow their brilliant and conscientious air support of 2 CORPS to be affected by this false cry of “Wolf”.’

These were potentially serious allegations from both camps. Kuter met both Tedder and Spaatz at Thelepte on 3 April to discuss Patton’s claims. Tedder, particularly, was furious with Mary and was insisting that he apologize. They then drove on to Gafsa to meet Patton, whom Larry thought seemed belligerent and unrepentant. ‘Patton appeared to me to act like a small boy who had done wrong, but thought that he would get away with it,’ Larry noted. Alex phoned while they were there and told Patton that he’d read Mary’s message and that the 2nd US Corps commander had asked for it. Spaatz also sided with Mary, telling Ike a couple of days later that ‘Coningham’s trouble was all caused by Patton’s distribution of his sitrep of April 1st, and that in view of its accusation notice had to be taken of it.’

On Tedder’s insistence, Mary later withdrew his signal and the following day visited Patton to apologize in person. Patton was initially wary, but Mary seemed sincere and they eventually shook hands and then lunched together. ‘We parted friends,’ noted Patton. But both Ike and Tedder had been angered by the whole episode. Tedder had felt it could have led to ‘a major crisis in Anglo-American relations’, as did Ike.

But this wasn’t about Anglo-US relations: Mary had been defending the US 12th Air Support Command. Rather, it was an argument over doctrine: air versus army. It was Ike and Tedder who turned it into a nationality spat instead. Once again, Ike felt he had to rebuke Patton, reminding him of the importance of maintaining Anglo-US unity and appealing to him to strike a sensible balance: yes, he expected Patton to show complete loyalty to Alex, but this did not mean he should not express his views and concerns to his commanding officer whenever he felt it was necessary. To a hothead like Patton, however, such a rebuke merely underlined his belief that Ike had sold out to the British.

But even the considerably calmer and more rational General Omar Bradley had been hurt by British criticism and had been deeply upset when, on 19 March, Alex’s COS, Dick McCreery, unveiled plans for the final conquest of Tunisia which were based on the assumption that once the Axis were squeezed out of the Gabès Gap, they would rapidly retreat to the next obvious defensive line at Enfidaville in the north, only forty miles south of Tunis. Since Eighth Army would already be in the plains and was by some margin the most experienced force within 18th Army Group, it was logical that it should be the hammer against this line of defence. First Army was already in the north, so Alex thought to use them in conjunction with Eighth Army in a strike from the west: 2nd US Corps, in the south, would play no role. It was one occasion where Alex’s diplomacy skills faltered. Bradley, especially, was outraged, because he knew that, by then, he would be 2nd US Corps commander. For the next few days, he seethed with anger every time he thought about Alex’s plan.

The Anglophobia and anti-Americanism should not be overplayed, however. Any group of commanders can rub each other up the wrong way and make decisions others feel angry and frustrated about. There were as many tensions among American commanders as there were directed towards the British, and vice versa. Of course, national pride played a large part, but then so did pride in one’s service, or division, regiment or squadron. And below command level, such feelings were less apparent. Among most American troops, Anglophobia was almost non-existent; and while many in Eighth Army undoubtedly felt they were superior to the Americans, they also believed they were a cut above those in First Army too. Alan Moorehead recorded an incident where a First Army soldier had gone up to an Eighth Army sergeant and said,

‘Hullo! Pleased to see you. I am from the First Army.’

‘Well, you can go home now,’ came the reply. ‘The Eighth Army’s here.’

But Eighth’s Army’s superiority complex was rather like that of a supporter of a football club at the top of the league when meeting a fan from a club at the bottom, and, with regard to the Americans, should not be confused with anti-Americanism. Bucky Walters felt that criticism of the 34th US Division was, in some ways, justified, and yet he never heard any British soldier grumble about them. ‘They didn’t criticize,’ he says. ‘They did whatever they could for us.’ As Guards Brigade intelligence officer, Nigel Nicolson, for example, found little evidence of any ill feeling between American and British troops. He felt that after Sidi Bou Zid, they had rallied well. ‘There is no bitter feeling left behind,’ he noted. ‘Nothing like a German-Italian relationship.’ He told his parents that ‘one of the most enjoyable half hours I have spent’ had been with an American officer as they had travelled together back through the Kasserine Pass.