The bombers had also returned believing they had successfully hit their target. One ship was seen to have been hit, while bomb blasts were also observed around the harbour installations. Even so, the Axis was managing to unload between forty and fifty thousand tons of supplies every month at Tunis and Bizerte. Since their goal was 60,000 tons per month at these two ports, the Allies were clearly not taking a great enough toll. In fact, overall, 75 per cent of Axis shipping was getting through, a figure that Ike knew was too high.

As ULTRA revealed, the combination of short shipping and air routes from Italy meant that the Axis was able to continue building up strength. Promised divisions from the Eastern Front had not been forthcoming; but by 13 February, von Arnim’s Fifth Panzer Army had 105,000 troops and over two hundred tanks, including eleven Tigers. Even so, the intelligence staffs at AFHQ in Algiers concluded that the current Axis supply situation allowed for only limited objectives and that a large-scale attack was unlikely. This was a fairly reasonable conclusion and one that was broadly accurate – on 7 February, for example, von Arnim warned the German High Command that his army was unfit for major offensive operations.

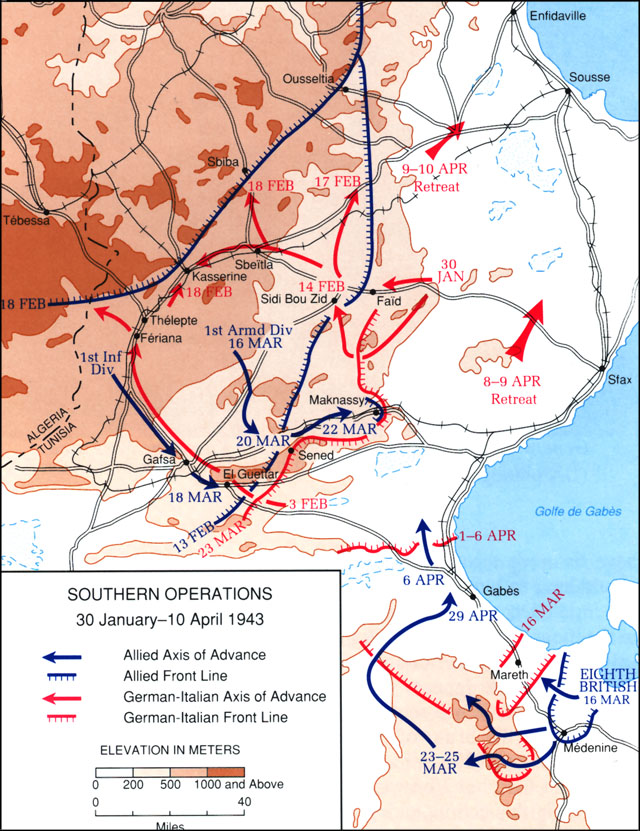

Enigma traffic was not as clear at the beginning of February as it had been, but in any case the intelligence staffs dealing with ULTRA decrypts still had to tally them with other intelligence gathered by a combination of aerial reconnaissance, POW interrogation, reports from agents, and ground observation. The process of marshalling this information was not helped by the muddled nature of the Allied command; even so, it was clear the Axis were planning something for the middle of February, and from ULTRA decrypts of 1 February this appeared to be an attack involving von Arnim’s 10th Panzer Division and Rommel’s 21st through the Fondouk–Ousseltia area.

Rommel’s star had waned considerably in recent months, however, and there is no doubt that he was held in far higher esteem by the Allies than by the German and Italian High Commands. Even Hitler was disillusioned with his former favourite. At the end of November, Rommel had visited Hitler and told him that if the supply situation was not radically improved, North Africa would have to be abandoned. This did not go down at all well, and Rommel was treated to a full-blown tirade, with Hitler reminding him that a sizeable bridgehead had to be maintained ‘for political reasons’.

However, to the methodical, solid wall of Monty’s Eighth Army, Rommel simply had no answer. Successive defensive positions were abandoned, leaving Eighth Army to untangle the latest web of mines and booby traps: El Agheila, then the Buyarat Line, then Tripoli itself. For some time, Rommel had been pressing for a retreat into Tunisia, where his German–Italian Panzer Army could link with Fifth Panzer Army. The Italians, to whom Rommel had always been answerable – on paper at any rate – did not see the military sense in this, only the disappearance of their last African conquest. ‘Resist [in Tripoli] to the last,’ Mussolini had told him. ‘I repeat: resist to the last.’

Eighth Army had reached just short of Tripoli by 19 January, and Monty began preparing an encircling manoeuvre, the tactic he adopted whenever the Panzer Army halted. Rommel again felt that the best option was to retreat into Tunisia and so called a summit with Kesselring and the Commando Supremo, demanding a definite ruling on whether he could abandon Tripoli. The Italians would not give him one – they needed to check with Il Duce first. Mussolini’s answer the following day was predictable: they must stay and fight. But two days later, with Eighth Army’s encircling movement already underway, Rommel decided to make his own decision and ordered Tripoli to be abandoned, telling Cavallero, the Italian Chief of Staff, ‘You can either hold on to Tripoli a few more days and lose the army, or lose Tripoli a few days earlier and save the army for Tunis. Make up your mind.’

Anything that could not be taken with them was, as far as possible, destroyed. The port installations were also mined and blown up, and the usual box of booby-trap tricks left for the new incumbents. And by leaving Tripoli, Rommel had given himself a breather. Monty needed to reorganize and regroup once more, to bring the long trail of his forces up together, and to clear and reopen the port.

Nonetheless, Rommel paid the price for disobeying his superiors. He’d been ill for some time. The violent headaches and ‘nervous exhaustion’ were taking their toll. At 5.59 a.m. on 26 January, he left Libya for the last time and crossed into Tunisia. Six hours later, he received a message from the Commando Supremo informing him that he was to be relieved of his command due to his ongoing sickness. The only caveat was that he could decide the timing of his departure.

Why Rommel failed to leave immediately is not entirely clear, but it appears that the chance for an all-out attack on the Americans and the opportunity to leave Africa with his reputation bolstered, if not restored, was too good a chance to miss, and so he began suggesting that his own Panzer army, as well as von Arnim’s, should launch a combined attack on Gafsa. If they hit the Americans sufficiently hard, then the Axis might be able to deal with Eighth Army along the Mareth Line without interference. This idea had been rejected, but on 8 February a more limited attack on Gafsa was proposed. The following day, however, Rommel met with both von Arnim and Kesselring. The Axis had their own personality issues: von Arnim and Rommel loathed one another; but at this meeting they did manage to agree on a policy for attack, one that was readily encouraged by the ever-optimistic Kesselring.

The last word from ULTRA related to the decisions of 2 February, but a week later those plans were completely out of date. Between them, Rommel and von Arnim had decided on a joint attack after all, although both would maintain their separate commands. The aim was to cripple the Americans, enabling Rommel to then deal with Eighth Army without interference. Despite Kesselring’s belief that they could push the Allies back as far as Tunisia, neither Rommel nor von Arnim shared this view. Operation Frühlingswind was to be a limited action after all.

The 48th Evacuation Hospital operated a leapfrogging system not dissimilar to the one used by Tommy Elmhirst for the Desert Air Force. The idea was that one unit went forward and took in the wounded closest to the action, then, when it was full, it would begin to evacuate the patients while the other unit leapfrogged and began the process all over again. Now, however, both units were in the front line: the 1st Unit at Thala, and the 2nd at Feriana.

The 2nd Unit had moved on 27 January into an old French barracks block, one storey high and with holes in the roof and windows that had long ago forgotten what it was like to be filled with tiles or glass. The corpsmen attached to the unit had filled in the holes with canvas and bits of cardboard, but with the weather as it was, any kind of building, whatever the state of disrepair, was preferable to operating out of a tent.

The nurses, as ever, had to live in pup tents outside, but Margaret Hornback was getting used to this new kind of lifestyle. They were now as near to the front line as they’d ever been and uncomfortably close to the airfield at Thelepte, a magnet for enemy air attacks. With this in mind, they decided they should make themselves a giant cross that they could then place on the ground to show that they were a hospital.

Painstakingly, the nurses sewed together fifty-four white sheets into a giant cross and then laid it out three hundred yards in front of the barrack block. In no time an American air force officer had hurried over and demanded to know what the hell they thought they were playing at. The nurses explained.

‘That flag there you’re bragging about,’ snarled the officer, ‘is not a Red Cross flag. When a white flag is put out on the ground like that it means the surrounding area is an airfield under construction.’

The nurses soon had this confirmed, but to make the kind of flag they needed would require another forty sheets and a hundred yards of unbleached muslin, and once again it would all have to be sewed by hand, at night, and whenever there was a lull. They stuck to their task, however, everyone pitching in, and it was soon finished. The corpsmen painted on a large red cross and then they laid it out and prayed it would not blow away. ‘If anything happens to that cross,’ one of the nurses commented, ‘I’ll take a chance on the bombs before I help make another.’

Margaret was still working as a nurse in the operating room and they soon found themselves pretty busy. The hospital could hold a maximum of two hundred patients. Those not too badly wounded were debrided – any infected tissue was removed – then were hurriedly shipped to an evacuation hospital further back, while the surgical team dealt with the most serious cases. These included an Italian soldier with a gangrenous leg – their first such case. Shortly after, another case arrived, this time a GI. Because of the risk of contamination to the operating room, both amputations had to be carried out in specially pitched tents outside the barracks.

The weather continued to be miserable. ‘We had a tiny fall of snow today – our first,’ wrote Margaret on 6 February. ‘The wind seems awfully cold.’ Not only that, it sent flurries of sand swirling around the hospital. ‘There’s always an inch of sand over everything, even if you’ve just cleaned,’ noted Margaret. One night there was a particularly bad storm, and the wind howled so strongly that the cook tent blew away and the wards were filled with sand that had been blown through gaps in the roof and walls. The amputees’ tents stood firm, however, but while the Italian was recovering well, the GI was losing his battle. Hour by hour the stench got worse, until it became almost unbearable. The nurses did what they could, but the day after the storm the American boy died.

Harry Butcher accompanied Ike to his meeting with Anderson on 1 February, which was held around the bonnet of a car on a windy day at Tulergma airfield, near Constantine. Anderson pointed out that their line was becoming worryingly thin now that the French had been all but pulled out. They were supposed to be preparing for an offensive in the north, but instead were struggling just to hold the line and respond to Axis thrusts. So Anderson suggested they should make Fredendall call a halt to his Maknassy drive and bring 2nd US Corps back into a mobile reserve.

Ike agreed – clearly there was no point frittering away American forces with futile aggressive operations that seemed to cost them dear and gain little. ‘Hereafter,’ noted Butch the following day, ‘they are to hit only when they know that they have heavy superiority.’

At varying times, both Anderson and Ike had talked of the need to pull back to the Grande Dorsale. This would have shortened the length of the front, brought them closer to their airfields and supply lines, and given them the passes through the mountains to form strong defensive positions. Here, they could have built up their strength with far greater ease. Neither, however, seems to have quite had the courage of his convictions, presumably fearing the loss of face and confidence this might cause. Instead, Ike ordered Anderson ‘not to leave the French unsupported in isolated positions and to concentrate his mobile forces in the south so that he may counter any enemy move immediately’. The problem was that Anderson couldn’t really support the French and keep his forces concentrated, and so 1st US Armored remained divided into the four different Combat Commands, and, for the most part, in the plains. Anderson was facing the same quandary as Neil Ritchie at Gazala in May 1942, and responding in exactly the same way: trying to cover the entire front, and in so doing splitting his forces into more and more penny packets – penny packets that could all too easily be gobbled up one by one by a more concentrated Axis force.

Among those now bivouacked in pup tents outside Gafsa were the US Army Rangers. Since the opening few days of the invasion, the Rangers had found themselves left behind in Algeria – where they had carried out further training and guarded Arzew. Since they were undoubtedly the best-trained US infantry unit in the invasion force, the decision to keep them in reserve was a somewhat odd one, but Fredendall certainly had plans for them now. Despite orders to go on the defensive, 2nd US Corps commander could not shake off his obsession with Sened, which was now back in Italian hands, and so on 9 February Fredendall told Colonel Darby that he wanted the Rangers to raid the outpost, with the aim of causing as much havoc and destruction as possible and capturing some prisoners.

At midnight on 10 February, three Companies, ‘E’, ‘F’ and Bing Evans’s ‘A’, with the headquarters mortar company in support, loaded onto trucks and began the winding journey up into the jagged mountains to the south of Sened Station. Twelve miles from Sened, the trucks came to a halt and the men clambered out. The plan was to walk cross country to within about four miles of the Italian outpost, lie up for the day, then attack under the cover of darkness.

The Rangers had practised this exact kind of operation time and time again. Bing Evans felt apprehensive, yet confident. Each man carried nothing other than his rifle, grenades, ammunition, first aid, and a small amount of rations, whilst on the back of each man’s helmet was a strip of white tape to make it easier for the man behind to see the one in front in the dark. Reaching their lying-up position without any difficulty, they spent the following day carefully watching the outpost. It lay on a long ridge, overlooking the railway station. There was a barracks block and various gun positions, but no gates or perimeter wire. The Rangers would be able to walk straight on in.

As darkness fell, they blackened their faces, checked their rifles, and then at around 11 p.m., as the moon dropped, moved a mile further forward then out into position, each company spreading out in a long line abreast so that they could attack simultaneously and give the impression of being in far greater numbers than the 180-man force they really were. ‘A’ Company was on the left of the line. Bing Evans had ditched his helmet in favour of his light wool cap. Underfoot, the ground was stony – each step had to be taken carefully – and the smell of sage wood wafted strongly on the cold night air.

The orders were not to fire until they were right in among them; they did not want to give the game away, and even if the Italians did open fire, in the darkness they knew their aim would almost certainly be high. Sure enough, when they were around a hundred yards from the outpost, an Italian sentry began to fire – and fire high. Moments later, the Rangers were upon them. One group of Rangers ran straight into the barracks block, where sleepy disorientated Italians were just beginning to wake up. With their commando knives, the Rangers cut the Italians’ throats.

Outside, flares were arcing into the sky. Suddenly, the place was lit up and Bing Evans turned and saw an Italian emerge from the shadows and rush towards him. ‘He was intent on killing me,’ says Bing, ‘and I looked into his eyes and saw they were big and frightened and bewildered and I just couldn’t pull the trigger on my .45. I froze.’ Then a shot was fired and the Italian slumped in front of him. Bing turned and saw Tommy Sullivan. He’d saved his life.

The mayhem continued, then, under cover of their mortars, they slipped away again into the darkness. One Ranger had been decapitated by a shell, but the rest managed to get away, including twenty wounded. With them were eleven prisoners. The damage they’d inflicted on the Italians was considerable: at least seventy-five dead, several guns destroyed, and long-lasting psychological harm. ‘Our job was to make the enemy uneasy and wary,’ says Bing. ‘There’s a difference fighting a cocky enemy and one that’s apprehensive.’

It was now about two in the morning and it was essential they got back to their positions before daybreak. Their task was made harder by the need to carry many of the wounded; but as Bing points out, adrenalin and the thought of being caught out in the cold drove them on. ‘We didn’t think about being tired,’ he says.

They all made it safely back. On finally reaching their bivouac, Bing suddenly felt exhausted and drained of emotion. They’d had two nights without sleep, had walked twenty-four miles over rough terrain, and been involved in an intense hand-to-hand action with the enemy. But the Rangers had proved that among 2nd US Corps there were some troops who were now not only well trained but combat experienced too.

Headquarters of the 1st US Armored Division was now in a large prickly-pear cactus patch just west of Sbeitla, a town still dominated by the ruins of the ancient Roman city. ‘This was not quite as undignified and impracticable as it sounds,’ commented Hamilton Howze. ‘The plants were some ten feet high, providing considerable cover in the bare, flat terrain.’ They even offered some protection against aerial attacks. Axis domination of the air had come as something of a shock to Hamilton, and his confidence had not been improved when he’d visited the 33rd Fighter Group at Thelepte. On the bulletin wall in the mess was a brightly coloured advert for an American aircraft manufacturer that had been cut out from a magazine. The strapline ran: ‘Who’s Afaid of the Big Bad Focke Wulf?’ Someone had written ‘Sign Below’. Every pilot had added his name.

Hamilton could understand why the new boys had found coming under aerial attack so alarming. He’d been frightened himself the first time, desperately flinging himself flat into a tyre rut, even though it was only an inch or two deep. But he had also realized that, in most cases, the damage caused by Stukas, in particular, seemed far worse than it actually was. The British had produced a booklet called How To Be Bombed, which whilst never denying the terrifying effect of bombing and strafing, listed many statistics to reassure the reader that the odds of surviving an aerial attack were actually pretty good. ‘In my job as G-3,’ noted Hamilton, ‘I took pains to get one of those booklets for issue to each man in the division.’

He was well aware that the division was not sufficiently trained and that they had not performed well in the recent fighting, but he also had great faith in Ward and felt that with encouragement and the opportunity to command his men properly, his boss would soon turn things around. And at least their men had now been blooded. Fredendall did not share Hamilton’s faith in Ward, however. Relations between the two had further broken down. Any suggestion Ward made, Fredendall immediately dismissed: when Ward asked for some aerial reconnaissance, the II Corps commander told him to mind his own business. ‘He is a spherical SOB, no doubt,’ noted Ward. ‘Two faced at that.’

‘Fredendall’s judgement was made on very infrequent visits of his staff officers to the forward area, and no visits at all by himself,’ noted Hamilton Howze. Instead, Fredendall continued to stay put in his command post at Speedy Valley, situated deep in a narrow gorge in the rock that could only be accessed by a single-lane track. Not content with the natural cover this offered, the II Corps commander had organized over two hundred engineers to excavate two tunnels deep into the walls of the ravine. For several weeks, his staff worked to the accompaniment of pneumatic drills as his underground headquarters painstakingly took shape. Speedy Valley was eighty miles from the front and only very rarely visited by enemy aircraft. That such a bunker was taking precautions to ridiculous extremes, or that the engineer battalion employed to build it might have been better used elsewhere, does not appear to have entered Frendendall’s increasingly wayward mind.

Pinky Ward’s frustration increased. Combat Command ‘B’ remained attached to the British with CCD in reserve, while Fredendall’s tight control over the rest of the division continued. He did eventually visit Ward at the command post near Sbeitla on 10 February, but this appears to have had little impact on his decision-making. On 2 February, Anderson had ordered Fredendall to keep a ‘small force’ in the Faid area to back up the remaining French – another half-hearted measure, but one that was based on Anderson’s belief that any future Axis attack through the pass would be merely a diversionary, small-scale thrust. But rather than leave Ward, as divisional commander, to make his own dispositions, Fredendall gave him a directive for the use of CCA and CCC that was so specific and so rigid as to make Ward almost irrelevant; he had become a supernumerary. In particular, Fredendall singled out two hills either side of the Faid Pass as the key features for the defence of the area to the west of the pass. On the Djebel Ksaira he placed one battalion of infantry, while on the Djebel Lessouda he positioned a further infantry battalion as well as a single battery of artillery and a few tanks. The two hills were ten miles apart, too far to be mutually supporting. As a result, the forces placed on them could not avoid operating in isolation of one another. A mobile reserve was also to be kept in the vicinity of Sidi Bou Zid, but this was now of insufficient size to be able to offer much resistance. Combat Command ‘C’, meanwhile, was to remain deployed further north, protecting the Fondouk area. Even a small Axis force of all arms would have little difficulty picking off these penny packets one by one.

Hamilton Howze was outraged, as was Ward, seeing this directive as not only deliberately insulting, but military madness, revealing just how little Fredendall knew about mobile warfare or understood about the terrain in which he expected them to fight. By contrast, Fredendall completely ignored the French forces of the Constantine Division, which came under his command. Also hopelessly split up, they were scattered throughout the area: some occupied positions near Sbeitla, another group was at Fondouk, while others were still stationed at Gafsa and Feriana. General Welvert, the French commander, tried to make suggestions, pointing out that, should they need to withdraw, his troops would need transportation. But such concerns appear to have fallen on deaf ears.

Ike also failed to show the courage of his convictions over Fredendall, who was by now a complete liability, as the Allied C-in-C was well aware. He’d already sent a warning note to Fredendall telling him not to stay in his command post. ‘Speed in execution, particularly when we are reacting to any move of the enemy’s, is of transcendent importance,’ he wrote. ‘Ability to move rapidly is largely dependent upon an intimate knowledge of the ground and conditions along the front.’ Then came the warning, echoing Marshall’s words to him a week before: ‘Generals are expendable just as is any other item in the army.’ There was no need for a warning, however. Fredendall should have been fired without one. This letter appears to have stirred Fredendall into visiting Ward’s Cactus Patch, but little more, as Ike discovered during his visit to the front on 13 February.

These had been strange and trying times for the Allied commander. He was desperate to get at the enemy, to launch the offensive and snatch Tunis, but what could he do? ‘I don’t suppose people at home can understand why things aren’t moving quicker,’ Lieutenant David Brown had written in a letter to his wife. ‘But if they were here, and realized conditions generally, among them the very big transport difficulties, they would appreciate the situation.’ He was echoing Ike’s thoughts exactly, but few in American or Britain did understand. The Daily Oklahoman had claimed that ‘Mud is a silly alibi.’ In England there were reports that there was increasing bitterness between British and American troops. Elsewhere in the press there was much speculation that Ike was about to be fired. Furthermore, his initial relief about the new command structure agreed at Casablanca had been dampened by a directive from the Combined Chiefs that specified the duties expected of Alex and Tedder when they took on their new roles. Ike saw this directive as a direct challenge to his authority. As Supreme Commander (as he was about to become), he and he alone, he believed, should be issuing his subordinates with their orders.

Then on 12 February he’d arrived back at the villa in Algiers only for Harry Butcher to offer him his congratulations.

‘What for?’ he asked.

‘On being a full general,’ Butch replied. He then explained how he’d heard the news on the grapevine. Following up the story, he had discovered it was true. ‘Goddammit,’ said Ike, ‘that’s a hell of a way to treat a fellow. I’m made a full general, the tops of my profession, and I’m not told officially!’ Shortly after, his wife Mamie phoned. It was true – Marshall had told her himself.

Now, on Saturday, 13 February, he was back near the front as a four-star general, and approaching 2nd US Corps HQ for the first time. He heard the din of hammers and drills coming from Fredendall’s command post long before his car actually reached the entrance. Truscott had warned his boss, but the sheer scale of the complex and the amount of time being wasted on its construction shocked Ike deeply. Approaching a young engineer, Ike asked if he’d helped prepare the front-line defences first before working on these bunkers. ‘Oh, the divisions have their engineers for that!’ came the reply. With a sinking heart, Ike then continued with an all-night inspection of the front lines. He found minefields that hadn’t been planted, forward positions inadequately prepared, and 1st US Armored Division still spread out in small groups. Worse was to come. Robinett, the CCB commander, was visiting Ward at the Cactus Patch when Ike arrived. Robinett told him that his reconnaissance parties had repeatedly ventured through the Fondouk area and found no evidence of any Axis military build-up. He had, he told Ike, reported this several times to his British superiors.

Ike left the Cactus Patch and drove on with Pinky Ward to Sidi Bou Zid to see the CCA command post. Just before midnight, he got out and strode off into the dark on his own, then paused a moment in the cold, still night. The biting winds and snow flurries of the previous few days had died down. Above him, the sky was clear and twinkling with stars, while the light from the moon outlined the shadows of the Djebel Lessouda to his left and the Djebel Ksaira to his right. Up ahead loomed the Faid Pass, that vital link to the plains beyond – the plains that held the key to victory in Tunisia.

Ike’s small inspection party began heading back before dawn. There had been little to cheer the Allied C-in-C and he determined to get changes made without delay. After being held up Sbeitla, and again when his driver fell asleep at the wheel and ran them into a ditch, they eventually managed to get going again and reach Speedy Valley. But by the time they arrived, Ike learned that the Axis had already begun their attack through the Faid Pass. For the moment, it was too late to make any changes.