After sucessful conclusion of first stage of Operation Compass (British offensive operation in Egypt) and British Commonwealth forces crossed into Libya and captured first Italian outposts in Capusso , they besieged Bardia , main Italian base and harbour in eastern end of Cyreneica. After that some organisati,onal changes made in Western Desert Force commanded by General O’Connor. 4th Indian Division was pulled out of line and sent to Sudan for campaign against Italian East Africa. Instead 6th and 7th Australian Divisions were brought in from Egypt for further operations in Libya and North Africa. Australian troops had a somewhat notorious dicipline especially for likes of unflexible British officers ( once Aussies were given free time in Palastine and Egypt they made somewhat a huge ruckus in Tel Aviv , Jerusalem , Cairo and Alexandria when they partied , made drinking contests in bars , frequent visitors of brothels in Red Light Districts , get into fights with troops from other Commonwealth nations and military/civilian law enforcement , sightseeing drunk on donkeys signing loudly in early morning , climbing over tramcars etc. But at frontline these rowdy Australians would prove themselves first class soldiers )

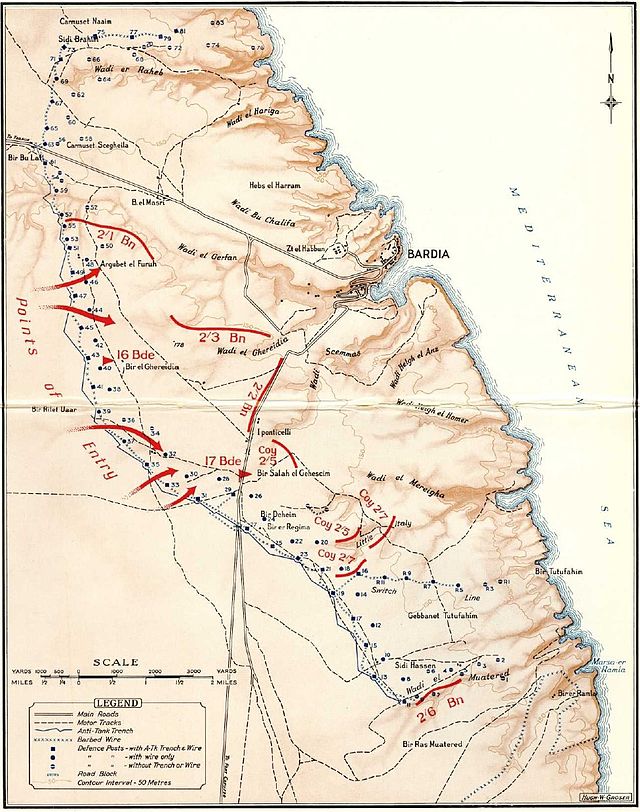

Next target for British Mediterranean Theater HQ in Cairo was Bardia and its besieged Italian garrison , entrenched behind several defensive belts (garrison was 45.000 man strong , made from five different Italian divisions remants of 10th Italian Army after Operation Compass plus original garrison and naval detachments , supported by 450 artillery pieces ) Mussolini had heavily fortified Bardia, though it was of dubious strategic value, as one of two key fortresses guarding Cyrenaica, the other being Tobruk. A small harbour town close to the Egyptian border, Bardia was enclosed by an 18-mile arc of outer defences, comprising an anti-tank ditch, minefields, barbed wire and eighty individual defensive posts. Impressive in scope, the defences were nevertheless flawed. However several Italian defensive belts in perimeter there were around Bardia , Italian defensive outposts were spread out such a way that could not support each other mutually and easy to take out from rear. Bardia, a small harbour town on the Mediterranean coast of Libya, is about 30 kilometres from the Egyptian border. It was developed as a military outpost during Italy’s colonisation of Libya at the beginning of the 20th Century and the Italians had fortified both the harbour and the town before World War II. Mussolini was confident that garrison commander General Annibale Bergenzoli would halt British advance before Bardia. This was a misplaced confidence. Italian garrison was static and morale was weak. On 27 December 6th Australian Division began to invest the town and permeter. Nocturnal patrols, in the proud tradition of their forebears on the Western Front, reconnoitred the enemy defences boldly at night. Compass in hand, the men would disappear into the darkness. When they reached the enemy lines, patrols would carefully record the amount of barbed wire present, the dimensions of the anti-tank ditch and the exact positions of the perimeter posts. Though quick to open fire on the intruding parties, the Italian defenders were also loath to venture out beyond their own lines. That meant no-man’s-land belonged to the Australians. The information assembled on Bardia’s defences convinced Mackay to begin his initial attack along a section of the western perimeter, at a site 2½ miles south of the road to Tobruk, along a gentle rise that would favour the use of the available tanks and artillery.

On January 2nd and 3rd , Royal Navy Mediterranean Fleet (battleships HMS Warspite , HMS Valiant , HMS Barham and monitor HMS Terror , gunboats HMS Ladybird and HMS Aphis) sailed from Alexandria and bombarded the town and its defences from seaward , causing massive damage among defenders and lowering already gloomy Italian morale further. Added to that was constant RAF bomber raids over perimeter. On 2nd January , under Royal Navy naval bombartment , a ravine overlooking the Bardia and its defences fell down over the town , causing heavy casaulties among defenders and destroying a number of Italian gun positions. Since Bardia was also blockaded both from sea and land , no supplies or reinforcements neither air support for defenders was incoming and Italian garrison morale was getting lower and lower. Under these conditions General O’Connor and 6th Australian Division commander General Iven Mackay decided to make an all out attack to breach Italian defensive perimeter in a junction point between two Italian defensive sectors at west by using Australian infantry and Matilda II tanks from 7th British Armored Division following short but intense artillery bombartment.

On 3 January 1941, the 2nd AIF (Australian Imperial Force) took part in the first major Australian battle of World War II at Bardia, Libya, when battalions of the 6th Australian Division penetrated the defences of the Italian stronghold. Despite some heavy resistance the town fell to the Australians just two days later. The Australians captured countless Italian war materiel as well as thousands of Italian prisoners of war (POWs), many of whom were shipped to prison camps in Australia.

The allied attack was launched at 5.30 am on 3 January 1941. The assault troops rose early on 3 January 1941, ate a meal and drank a tot of rum. The leading companies began moving to the start line at 0416. The artillery opened fire at 0530.

The troops wore their greatcoats to keep out the intense cold of the desert at early morning , drunk a tot of fighting rum and entered the fight singing and shouting. After the engineers blowing holes through wire obstacles with Bangalore torpedoes and opened up gaps in Italian minefields under fire, the infantry captured a number of enemy posts within half an hour – thus establishing a breach in the perimeter. After filling anti tank ditch , Australian infantry attack forces with support of British Matilda tanks and artillery fire began advance and penetrate enemy defences then began to veer left and right to take out Italian defence posts , bunkers and trenches with considerable speed and sucess.

The fighting continued on until 5 January when the Italian position in whole Bardia had been cut almost into two by Australian infantry advance with support of Bren gun carriers and Matilda tanks from 7th Armored Division. Italian defence was mixed , some Italian positions and bunkers held till last man (or last bullet before giving up) , several though surrendered after first encounter with Australian infantry and British Matilda tanks. Australian troops learned a healthy respect against Italian artillery which caused several casaulties in 17th Australian Brigade which was conducting a diversionary attack on south of defensive perimeter. At the other hand British Matilda tanks with three inch armor were specifically designed to support infantry (I tank) and Italians lacked anti tank guns and their field artillery were inefficient against Matilda tanks due to lack of armor piercing rounds , Italian shells bouncing off their armor.

An Australian soldier wounded in the first day of fighting later described the capture of one of the perimeter posts and Italian POWs captured there: “[They] started to came up from below with their hands up and we searched them and sent then back to the rear. I found a grenade in the pocket of one of them and when I took it from his pocket he snatched it back, saying something in his own language. Thinking he was going to blow us both up, and the safety catch on the rifle being on, I was just resigned to having to use the bayonet on him when the grenade came apart, it was full of cigarettes instead of explosives much to my relief. The next [Italian] was only about 17. He was shaking with fear and white as a ghost and had been wounded on the hand. I felt sorry for him and gave him a smoke, tried to tell him that he would be alright and there would be no more war for him.”

By 5th January after reaching out of the town 16th Australian Brigade and 19th Australian Brigade which were conducting main attack , turned left and right to take out Italian defensive bunkers and trenches in north and south sectors from rear. That was when the garrison began to surrender en masse. The allies took more than 43,000 Italian prisoners (in addition 1.000 killed Italians) and considerable amounts of enemy weapons, supplies and equipment. The battle for Bardia cost 130 Australian lives with 320 men wounded. Italian garrison commander General Bergenzoli (nicknamed “Electric Whiskers” by British) bugged out of town along with his staff and a few hundred troops from a gap in Australian lines at coastal road just before the town surrendered. Having been defeated by a smaller force, the humiliated Italian general put it about that he had been attacked by four Australian divisions with 1000 tanks, and Mussolini himself broadcast on radio that Bardia had gone down gallantly against a force of 250,000.

Italian POWs captured in Bardia.

The victory at Bardia enabled the Allied forces to continue their advance into Libya and capture almost all of Cyrenaica. As the first battle of the war to be commanded by an Australian general, planned by an Australian staff and fought mostly by Australian troops, Bardia was of great interest to the Australian public; congratulatory messages poured in and AIF (Australian Imperial Force) recruitment surged. John Hetherington, a war correspondent, reported that,

Men who since childhood had read and heard of the exploits in battle of the First AIF, who had enlisted and trained under the shadow of their fathers’ reputation as soldiers, had come through their ordeal of fire and built a reputation of their own.

— Hetherington

In the United States, newspapers praised the 6th Australian Division. Favourable articles appeared in The New York Times and the Washington Times-Herald , which ran the headline “Hardy Wild-Eyed Aussies Called World’s Finest Troops”. An article in the Chicago Daily News told its readers that Australians “in their realistic attitude towards power politics, prefer to send their boys to fight far overseas rather than fighting a battle in the suburbs of Sydney”. During the battle, Wavell had received a cable from Imperial Chief of Staff General Sir John Dill stressing the political importance of such victories in the United States, where President Franklin D. Roosevelt was attempting to get the Lend-Lease Act enacted; it became law in March 1941.

Mackay wrote in a diary note on 6 January that the “Germans cannot possibly keep out of Africa now.” In Germany, Adolf Hitler , was unconcerned by the military implications of the loss of Libya but deeply troubled by the prospect of a political reverse that could lead to the fall of Mussolini. On 9 January 1941, he revealed his intention to senior members of the Wehrmacht to send German troops to North Africa, in Unternehmen Sonnenblume ; henceforth, German troops played an important role in the fighting in North Africa.