A series of posts I will make regarding the service of Canadians in other theatres of the Second World War. My sources include:

Reader’s Digest: The Canadians at War 1939/1945, Volumes 1 & 2.

Great Canadian Battles

Great Canadian Battles: Heroism And Courage Through The Years

Everyday Heroes: Inspirational stories from Men and Women in the Canadian Armed Forces.

Hopelessly outnumbered and ill-prepared, two Canadian battalions go down fighting the Japanese at Hong Kong

Meanwhile, the exhausted Rifles to the east were now the core of the force in the Stanley Peninsula. Only a few detachments of Middlesex and Volunteers were left to help them. In the days that followed, the Rifles fought under every conceivable disadvantage. The astonishing fact is that they not only clung to their positions so long, inflicting losses and delaying the Japanese, but actually were able to mount numerous counter-attacks.

(Japanese aircraft during an air raid over Hong Kong, exact date unknown.)

For the Rifles, each desperate battle meant more irreplaceable losses. Yet somehow they held on day after day. Food and water were cut off. Sub-units were broken up, killed captured. Nor was it any better where the Grenadiers fought. The Royal Scots had tried an unsuccessful counter attack on the 19th with heavy losses. Still there was no thought of surrender. The Grenadiers’ D company was led by Captain Bowman who, someone said, “was so exhausted he was talking gibberish.” Ordered to attack a Japanese strongpoint on Mount Houston, Bowman was last seen charging forward with a tommy gun in hand. Two more officers were wounded and two platoons almost annihilated before the third managed to seize ground vitally needed by the enemy. Its men commanded the one north-south road across the island and stopped the enemy advance till December 22nd when their shelter was finally smashed by artillery. The survivors were taken prisoner. When the Japanese officer heard how few men had held them off, it is said he slapped the Canadian officer for lying.

While that was going on, HQ Company, with parts of C company, had obtained a foothold at the Gap, fighting under Maj. E. Hodkinson, who was wounded. B company under Major Hook joined C company on the 20th, and that night in heavy rain and fog attacked Mount Nicholson. They were driven off, leaving 20 men and two officers on the slope. They renewed the attack at dawn. The casualties included all the officers, seven NCOs and 29 men. As the fighting raged on, those who were taken prisoner were marched off, shot or left in exposed positions to be blown up by their owns fire. The wounded were generally bayoneted.

Everywhere now the defenders were fighting with their backs to the wall, in shrinking positions. The colony rejected a third surrender demand even though 25,000 enemy troops were pouring across the island, and more stood behind them. The exhausted Allies tried to hold a last desperate line to the west to protect the towns of Victoria and Aberdeen with their civilians. Hospitals crammed with wounded threw themselves on the mercy of the invaders.

In the south, shortly before 6:00 Christmas morning, about 150 to 200 Japanese soldiers broke into the emergency hospital at St. Stephen’s College and started to bayonet the wounded in their beds. Two doctors who tried to stop them were shot, then bayoneted for good measure. Before the massacre ended 56 patients had been stabbed to death; three British nurses were killed, and the Chinese nurses were raped. Similar situations repeated themselves across the island. Many prisoners were either executed on the spot or killed shortly thereafter. Capt. James Barnett, a padre, recalls a force of Japanese soldiers herding him and around 90 others into a room, taking anything of value they had on them (Jewelry, watches, wallets, cash), throwing cartridges in their faces, and executing two riflemen who were singled out and taken away from the rest.

It was over not long after that. At 3:15 PM Christmas Day, General Maltby ordered a ceasefire. There was no point in continuing. Mobs were rioting in the towns. There was no water. Communications had broken down. A few pockets of resistance continued, but for the rest the silence of defeat settled over the hills. We lay down our arms, some shocked, some relieved, some fearful of being tortured and executed.

A Grenadier recalls: “We watched the Union Jack come down and the Rising SUn go up. It was a very empty feeling.”

The battle had lasted 17 and a half days. The Japanese admitted around 3000 casualties, roughly 1000 more than the defenders. The Canadians counted 290 men dead, 493 wounded. But for those of us who had survived, the worst was yet to come. We were packed into a Chinese refugee encampment on the island and later into barracks on the mainland. For months there were no accurate casualty lists for anxious families in Canada. For three years and eight months the indescribable ordeal of imprisonment continued, full of death, disease, beri-beri, epidemics, starvation, brutality. Dragging our sick bodies to labour in the tropic heat at bayonet point. Of the 1975 Canadians who sailed from Vancouver, 555 never returned. Nearly half of this number died in prison camps.

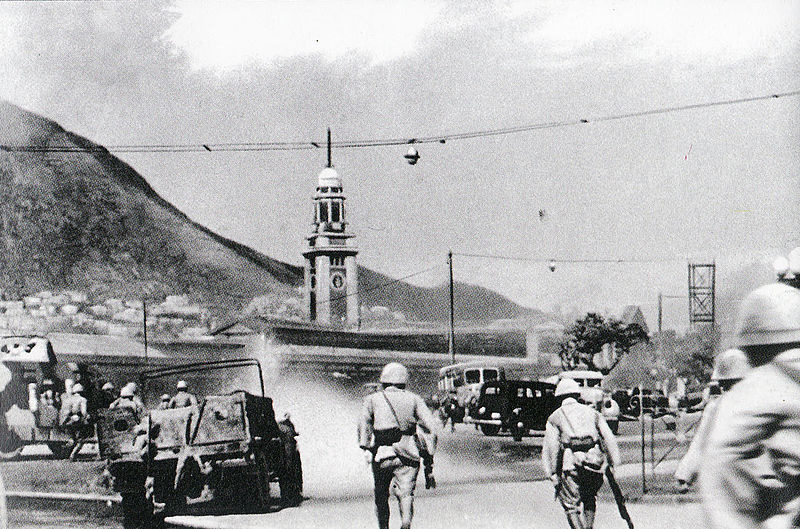

(Japanese troops in Kowloon sometime after taking the city.)

At home, controversy raged over the Hong Kong affair. George Drew, Ontario Conservative leader, charged that the whole expedition was mismanaged and ill-prepared. A Royal Commission study by Chief Justice Sir Lyman Duff found a number of things to criticize but “no dereliction of duty on the part of the government or its military advisers.” This was branded “whitewash” by the Opposition in Parliament and by others.

I find myself with some final notes on the subject. Somethings I consider worthy of remembrance.

A squad of Free French soldiers were also present under Captain Jacques Egal. They fought with the HKVDC at North Point Power Station. They are reported to have acquitted themselves well. They and the HKVDC they fought with at the Power Station were all World War One veterans.

Around 40 Royal Marines were present (attached to HMS Tamar). They fought alongside HKVDC and Royal Engineers at Magazine Gap.

The Chinese Military Mission to Hong Kong, initiated in 1938, was headed by Rear Admiral Chan Chak and his aide Lieutenant Commander Henry Hsu; it had the objective of coordinating Chinese war aims with the British in Hong Kong. Working with the British police, Chak organized pro-British agents among the population and rooted out triad factions sympathetic to the Japanese. On Christmas morning, Young informed Chak of his intent to surrender. Chak intended to break out and was given command of the five remaining Motor Torpedo Boats; 68 men, including Chak, Hsu, and David Mercer MacDougall were successfully evacuated to Mirs Bay where they contacted Communist guerrillas and were escorted to Huizhou. For this feat Chak was made an honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire

Hong Kong and Singapore Royal Artillery, which was raised with troops recruited from Undivided India, also suffered heavy casualties during the Battle of Hong Kong and are commemorated with names inscribed on panels at the entrance to Sai Wan War Cemetery: 144 killed, 45 missing and 103 wounded.

(Canadian and British prisoners-of-war awaiting liberation by the boarding party of HMCS Prince Robert, August 30th, 1945.)