A series of posts I will make regarding the service of Canadians in other theatres of the Second World War. My sources include:

Reader’s Digest: The Canadians at War 1939/1945, Volumes 1 & 2.

Great Canadian Battles

Great Canadian Battles: Heroism And Courage Through The Years

Everyday Heroes: Inspirational stories from Men and Women in the Canadian Armed Forces.

Hopelessly outnumbered and ill-prepared, two Canadian battalions go down fighting the Japanese at Hong Kong

For two years the army had been marshalling the bulk of its strength in Britain. For two years there had been rumours that Canadian soldiers were going into action in France, then Norway, the Middle East, in invasion for the liberation of Europe, almost anywhere but where action finally came.

When it came, briefly, in December 1941, it involved neither the liberation of Europe nor the four divisions mustered in Britain for that ultimate purpose. It involved the defense of an Asiatic outpost of the British Empire that belonged to no division at all. Hong Kong was a disaster. Ian Adams in Maclean’s, compared it to the Charge of the Light Brigade, “an act of stupidity and folly” that sent inadequately trained and ill-equipped men to defend an island that was indefensible. Britain requested the two infantry battalions in September 1941. This reinforcement of the Hong Kong garrison, said the British government, would “reassure Chiang Kai-shek as to our intention to hold the colony and have a great moral effect throughout the Far East.”

Unmentioned was the view Winston Churchill had dictated to his Chief of Staff on January 7th, when such a possibility was first broached:

“…This is all wrong. If Japan goes to war there is not the slightest chance of holding Hong Kong or relieving it. It is most unwise to increase the loss we shall suffer there. Instead of increasing the garrison, it ought to be reduced to a symbolic scale. We must avoid frittering away our resources on untenable positions. Japan will think long before declaring war on the British Empire, and whether there are two or six battalions at Hong Kong will make no difference to her choice. I wish we had fewer troops there, but to move any would be noticeable and dangerous.”

Churchill was accurate in his appraisal of what would happen in the event of attack. And by late 1941, with Britain’s fortunes at a low ebb, Japan was nearing the end of her long thinking. She had been ravaging China for years; she had made no secret of her dreams of advancing further into Asia. She had joined Germany and Italy in the Triple Alliance. Her plans for conquering Hong Kong had in fact been laid as early as July 1940. The codeword for attack was “Hana-Saku, Hana-Saku,” literally “flowers abloom, flowers abloom.” The three divisions that would answer it were massed within thirty miles of Hong Kong when the Canadians sailed.

Only nine days before the Canadian force did sail, Gen. Hideki Tojo became Prime Minister of Japan. Lord Halifax, British Ambassador in Washington, promptly warned London and Ottawa that this made war inevitable and that it would be absurd to commit more men to Hong Kong. He suggested Ottawa re-examine its policy. According to his war histories, Winston Churchill himself, in approving the request for Canadian troops had “allowed myself to be drawn from” his position in January. But he had called for “a further assessment before the battalions sail.” A day before departure, London told Ottawa war in the Far East was “unlikely at present.”

Ottawa stuck with its decision. Lt. Gen. Maurice Pope, then Assistant Chief of the General Staff, says in Soldiers and Politicians:

“I heard a member of the government say they had been actuated by solely by two ideas: A, that it was unthinkable that Canada should seek to fill only the comfortable roles and, B, that Britain was in a difficult spot and frankly seeking a helping hand. In these circumstances, any thought of refusing the request had never occurred to them.”

It was hoped the Canadians would see only garrison duty. But the directives to their commanding officer also said they would “participate to the limit of your strength in the defense of the colony should the occasion arise.” The need for secrecy and speed was considered so vital that the entire expedition was whipped together in little more than two weeks. Its core was the two infantry battalions, both classified by army headquarters as “in need of refresher training or insufficiently trained and not recommended for operations.”

(Infantrymen of “C” Company, Royal Rifles of Canada, disembarking from HMCS Prince David (AMC), November 16th, 1941.)

One of the battalions was Quebec’s Royal Rifles of Canada under Lt. Col. W.J. Home; it was just back from garrison duty in Newfoundland. The other was the Winnipeg Grenadiers under Lt. Col. J.L.R. Sutcliffe; it was just back from garrison duty in the West Indies. In addition, there was a brigade HQ with a signals section and other specialists. The entire force of 1975 men was under Brig. J.K.Lawson.

They sailed from Vancouver the night of October 27th, in the converted passenger ship Awatea and the Armed Merchant Cruiser Prince David. Their departure was secret. Her destination was unknown to most of those aboard. Her fate was to deliver the Canadians into one of the most tragic episodes of the country’s war. One of the Canadians aboard was a signalman named William Allister. He would write a novel after the war about the Canadians at Hong Kong titled, A Handful of Rice. The following is his account of the expedition and battle, based on his own diary, on interviews he made for CBC broadcasts, and on material from official records.

"…As a member of the HQ signals section, I was among the hundreds who had assembled in Ottawa in an atmosphere of tense speculation. My diary reads: “Left home for the last time. Couldn’t tell them it was embarkation leave. Goodbye’s were hasty, which is best. Mom is sure I’ll be back weekends. The notice said: ‘You are wanted for special duties overseas.’ Sounds important and frightening. But what the hell, anything official is always ominous. All kinds of rumours were flying. Startling and exciting. Then we’re told to pack and issued summer uniforms. We are going in a day or so, and to a hot climate. Africa? jamaica? could be. More probably China, and I’ve never been farther west than Winnipeg. It’s too fantastic! The depot’s jumping, crowds pouring in and all hush-hush.”

Within a few days we were speeding across the country When we got aboard the Awatea in Vancouver, things began to go awry. Our vehicles were late; they came on another ship and never did reach us. (The vehicles were being transported to Hong Kong aboard the US Merchant Vessel San Jose. At the outbreak of war in the Pacific, she was diverted to Manila by request of the US government.) There was immense confusion and no fanfare. The soldiers unwittingly began to echo Churchill’s prophetic words that this was “all wrong.” A sense of doom seemed to creep through our ranks. Resentments flared. Awatea zigzagged across the Pacific to avoid submarines. It was anything but pleasant; nauseating conditions for the men, rumors of submarines, doubts of what lay ahead. Our lone escort, The Prince David, often fell so far behind she was out of sight.

A few days out of Hong Kong we were told of our destination and that we should be ready for anything, even fighting our way ashore. A corporal: "I guess they felt Tojo’s hoopla about conquering the world was grounds for suspicion. When I watched the briefing I said, ‘My God, another Dunkirk!’ And someone answered, ‘No fella, at Dunkirk they had somewhere to go.’ "

My diary: “Before we landed on November 16th our brains were addled with precautions about everything from sexual diseases to the customs of Indian soldiers who would train with us. But how could anyone prepare green Canadian kids for the impact of the Orient? Our first shocker was seeing crowds following the ship in sampans, eating garbage we threw overboard. The waterfront stench made it almost impossible to breath. It was an odour you could practically taste.”

“On landing, we found that our main positions were on the island of Hong Kong but our barracks was on the mainland nearby. We route-marched through Hong Kong’s sister city of Kowloon to our barracks at Sham Shui Po. All the pomp and ceremony made us feel like an army of occupation amid the teeming Chinese. The filth, poverty and verminous atmosphere hung over us like a pall. I wanted to pull on gloves and a gas mask when I thought of the cholera, dysentery, malaria, typhoid, venereal disease around me. Barefooted old women bent low under huge loads while coolie bosses bellowed behind them. We saw filthy shops and meat black with flies; harmless beggars, their diseased legs half eaten away; white men in Panama hats riding rickshaws right out of a Hollywood movie. Neon in Chinese. Nothing connected. Time seems to be motionless, A weird sensation.”

“Slept under mosquito netting like Clark Gable in China Seas, nearly eaten alive by bedbugs the first night. Hired a valet for 28 cents a week. He shines our shoes and buttons, presses our uniforms, gets an amah to do our laundry, makes our beds, runs errands, serves tea in bed. US cigarettes are ten cents a deck. Beer ten cents a bottles. Bills stick out of our pockets. The beggars mob us, to the point where its hard to walk. We get shaved in our sleep, for five cents a week! What a time! Gals galore. Thousands of refugees fleeing ahead of the Japanese at Canton. Prostitution seems to be a national sport. But the girls are often just nice kids sold by their parents for about $200 just to keep the family alive.”

Everything was dirt cheap. Servants waited on us hand-and-foot. There was a kind of hysteria in the air. Who could believe there were 50,000 to 60,000 seasoned Japanese troops only 30 miles away? That spies might be all around us in this colony of 1,500,000 people? Posing as barbers, tailors, dentist, these Japanese spies and a Chinese fifth column were everywhere, even inside our barracks. Warehouses were leased by fifth columnists and used to construct foundations for heavy artillery. The popular barbershop in the Hong Kong Hotel was their intelligence HQ and the top brass in the colony were among its clientele.

We did some training and got to know a bit about the countryside, but the three weeks we had were tragically inadequate for what lay ahead. The island of Hong Kong we had to defend was 29 square miles in area, a rugged, confusing mass of mountains, hills and valleys with almost no flat ground. It was only a half mile across to the mainland peninsula of Kowloon. Beyond that to the north lay more mountainous land called the New Territories, which stretched 30 miles up to the border with China. Information on the defenses was not reassuring. There were 36 guns, but the mobile artillery had none of the latest models. There were 20 early model AA guns but no radar equipment. There were five old-fashioned RAF planes (Two Supermarine Walrus amphibious aircraft and three Vickers Vildebeest torpedo-reconnaissance bombers) but no hope of more. Most naval units had withdrawn, leaving only a few small vessels.

We stood alone. Still the Governor, Sir Mark Young, and the military commander, Maj. Gen. C.M. Maltby, appeared to believe that Hong Kong could be defended. There was good for 130 days. The total defense force added up to fewer than 14,000, including nurses and civilian volunteers. Besides the Canadians, there were three regiments of the Royal Artillery containing many Indian troops, one Indian regiment with British officers from the Hong Kong and Singapore Artillery, two engineer companies, one British Infantry battalion (Royal Scots), one British Machine-gun battalion (Middlesex Regiment), two Indian infantry battalions (7th Rajput Regiment and the 14th Punjab Regiment) and the Hong Kong Volunteer Defense Corps, a militia outfit.

My diary: “We were camping out in tents at Waterloo Road, setting up signal offices, exploring the Chinese mansions, singing, laughing. We drive north into the New Territories and saw lots of pillboxes and gun emplacements, nice and solid looking. It looked like a cinch that Japan wouldn’t dare start a fight; she had her hands full with China. The boys were on a tourist spree, brining back kimonos, dressing gowns, pajamas. Steaks at Jingles were two inches thick and a foot and a half long. all for two bucks. What a life.”

“Nothing to worry about,” I wrote home. “Those poor guys in England getting bombed and living on rations, and us living like kings. You can rest easy, Mother me dear, the war is thousands of miles from your darlin’ boy.” The letter went off on the China Clipper on December 7th, and was shot down by the Japanese. Time had run out.

On the morning of December 8th, Hong Kong time, (December 7th in North America) some of us were shaving when we heard the air-raid sirens. We paid no attention. “The usual rehearsal,” my diary says. "We heard this booming and figured it was artillery practice. Jenkins went out on the balcony to look at the harbour and saw aircraft swooping down. He came in very surprised “They’re dropping bombs,’ he said. We just laughed. We nearly died laughing. The windows were blown in and we hit the deck. They were aiming at our building, they seemed to know where everything important was. We beat it out of the building. Ronny and Fairley were hit. Shrapnel was flying and Rutledge hollered for us to lie flat. We saw a Chinese coolie get his head blown off. At the camp gates there were about 50 Chinese bodies piled up. We had the distinct impression that there was a war on.”

The news of war filled the airwaves. Sneak attack on Pearl Harbour, Much of the US Pacific fleet taken out of action. Emergency sessions of Parliament. Declarations of war by the United States, Canada, Britain. But we were in Hong Kong, isolated and far from home. Our two infantry battalions were already in their positions on the islands and our signals section with the defenders of Kowloon Peninsula and the New Territories.

The closer we looked the more impossible the situation seemed. The useless aircraft were destroyed on the ground, giving the Japanese a carte blanche in the air. And their planes could fly too low for AA guns to take aim. The garrison was vastly outnumbered and outgunned. There was no hope of reinforcement. Britain’s two great battleships, Prince of Wales and Repulse, were sunk by aircraft off Malaya within a few days. The US fleet was crippled; the Chinese armies could offer no help. We found ourselves pawns in a huge power play, caught in the center of a hopeless, suicidal frontline position.

The enemy we faced was made up of hardened veterans seasoned by years of war in China. Our Canadian force was deemed adequate only for garrison duty. You couldn’t compare us to the trained Canadian divisions in England, they at least had spent years preparing for an invasion. Neither of our battalions had trained in anticipation of battle and to make matters worse, amny reinforcements ent to the infantry units were raw recruits or little better. One private had had exactly 30 days of training, during which he had learned how to left turn, right turn, and salute. Didn’t fire a shot until Hong Kong. Another man, a corporal, taught one fellow how to load and fire his rifle behind battalion HQ in the hills. A lieutenant remembers how some of his ‘soldiers’ were just too damn young. “I remember coming upon a man who was wounded, and discovered he was a boy, barely 17.” One private remembers, embarrassingly and tragically, some Canadians throwing their grenades at the Japanese without pulling the pins, they did not know how to use them.

Here I will move away from the story of William Allister, as I wish to give a broader view of the Battle for Hong Kong. As Mr Allister mentioned regarding the refugees in the city, on the 21st of October 1938, the Japanese had invaded Canton (Guangzhou), thus surrounding Hong Kong. According to the history manual of the United States Military Academy: “Japanese control of Canton, Hainan Island, French Indochina, and Formosa virtually sealed the fate of Hong Kong well before the firing of the first shot”. British military in Hong Kong grossly underestimated the capabilities of the Japanese forces and downplayed the Japanese threat as ‘unpatriotic’ and ‘insubordinate’. US Consul Robert Ward, the highest ranking US official posted to Hong Kong in the period preceding the outbreak of hostilities, offered a first-hand explanation for the rapid collapse of defenses in Hong Kong by saying that the local British community had insufficiently prepared itself or the Chinese populace for war besides highlighting the prejudiced attitudes held by those governing the Crown Colony of Hong Kong:“several of them (the British rulers) said frankly that they would rather turn the island over to the Japanese rather than to turn it over to the Chinese, by which they meant rather than employ Chinese to defend the colony they would surrender it to the Japanese.”

According to US Consul Robert Ward, “when the real fighting came it was the British soldiery that broke and ran. The Eurasians fought well and so did the Indians but the Kowloon line broke when the Royal Scots gave way. The same thing happened on the mainland.”

On the morning of the 8th of December just after 8:00 AM and only four hours after the Pearl Harbour attack, the Japanese attacked Kai Tak airport, destroying the few RAF aircraft present, and also taking out the few civil aircraft used by the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps (HKVDC). Two of the RN’s three remaining destroyers were ordered to head for Singapore. Only HMS Thracian, and a small flotilla of gunboats and torpedo boats remained. On the 8th, 9th and 10th of December, 8 American pilots the CNAC (Chinese National Aircraft Corporation) and their crews flew 16 sorties between Kai Tak airport and landing fields in Namyung and Chungking, the wartime capital of the Republic of China. 275 people (government officials and their families) were evacuated.

The Commonwealth forces decided against attempting to hold against the Japanese at the Sham Chun River and instead the three forward battalions fell back to the Gin Drinkers Line. These were the Royal Scots, and the two Indian infantry battalions; the 7th Rajputs and 14th Punjab. The line was built by the British to protect the colony from the Japanese, and had sometimes been called the “Oriental Maginot Line”. It was a series of pillboxes and concrete defences stretching across the isthmus about five miles north of Kowloon. The Canadian Signals Sections was attached to them, the first Canadian Army troops to see combat in the Second World War. The Japanese 38th infantry division under Major General Takaishi Sakai quickly forded the river over temporary bridges. Early on December 10th, the 228th Infantry Regiment under Colonel Teihichi of the 38th Division attacked the Commonwealth defenses at the Shing Mun Redoubt defended by the A Company of 2nd Battalion Royal Scots under Lieutenant Colonel S. White. The defenders were surprised to find that the World War 1 tactic of holding one long line outmoded, surprised that the propaganda stereotype of the Japanese as myopic barbarians who couldn’t see in the dark was fatally wrong. The proved to be quite adept night fighters.

Here I return to the diaries of William Allister, as his friend “Wallie” was attached to Signals Section, and told his friends what he had seen at the front lines:

“Wallie had to ride back and forth to the front lines. Said its bloodcurdling to hear the Japs battlecries. They came charging right into the machine guns. Our men used their machine guns, Lewis, the Bren, old Vickers guns. Fired until the barrels were red hot. The Japanese went down like wheat and still they kept coming, climbing over bodies to get at us. The pillboxes turned out to be death traps, too easy to get grenades inside them. The Japanese would just throw until they got one in the air vents. The men just set up on the roofs of the pillboxes instead, doctrine be damned. The Indians were loving every minute of it. They’d hold their fingers down on the triggers and never stop, yelling war cries back at the Japs. They looked depressed when they were ordered to retreat.”

The line was breached in five hours and later that day the Royal Scots also withdrew from Golden Hill until D company of the Royal Scots counter-attacked and re-captured the hill. By 10:00 the hill was again taken by the Japanese.This made the situation on the New Territories and Kowloon untenable and the evacuation to Hong Kong Island started on 11 December, under aerial bombardment and artillery fire. D Company of the Winnipeg Grenadiers went across from the island to help and saw action briefly on the same day. By that point the Royal Scots and Indians fighting the rearguard were fighting on nerve alone. D company was ordered to cover the withdrawal that night, while the 7th Rajputs were left to hold Devil’s Peak peninsula, a last mainland defense. All this sounded great on paper, but the withdrawal had to be organized alongside the chaos of half a million Kowloon citizens scrambling to escape across the half-mile of water. Panic and hysteria swept through the waterfront. Fifth columnists fired at soldiers and civilians alike. Boats, sampans, junks, ferries, jammed with terrified refugees, poured over the water towards the islands. Sometimes they took hits intended for the soldiers. The aerial bombardment and artillery never let up. Mobs looted warehouses, Police fired into crowds, Soldiers destroyed vehicles and ammunition. Last-minute demolition crews tried to destroy any harbour or military facility that might be of value to the Japanese. The Canadian signals section were kept at their posts until the 12th, then ordered to get away as best they could.

From William Allisters diary:

"We got our equipment on two trucks and went roaring through the streets, rifles pointed upwards in fear of snipers. Riotous confusion everywhere. The civilians had no weapons. Families were split, An old lady stretched out a hand for help as we passed. We couldn’t help. They all had to be left behind. Rounds falling everywhere. One blew a crater right in front of us. We backed up and took a side street. People running everywhere. At the dock we had to carry the signal sets (they felt like pianos) through the mobs and load them on a boat. Ha, what boat? Bedlam. Everyone trying to get a boat, prices through the roof. Every floating board up for hire. One drunken police sergeant, laughing happily, shooting at anyone, looter or not, as long as he was a coolie. Good clean fun to him. One guard at a warehouse was letting looters inside, then gunning them down.

“We took a ferry at gunpoint but its engine kept stalling. Just as we got into the water, Japanese aircraft came in on a dive-bombing run. The shore was lined with people with no way to cross. A munitions ship took a hit further out and lit the entire city up with the blast. We had no life belts and I couldn’t swim.”

“We finally made it across and got a truck to Victoria barracks, just in time to run into the worst shelling ever. We were near a munitions depot they were trying to hit. We lay along the cement passage and each time I heard the split-second hiss I flung my hands over my helmet on reflex. One shell blew my helmet off and through the smoke I saw Blackie waving it on the end of his bayonet where it had landed.”

“We all lay down to sleep exhausted. But I couldn’t sleep. We sat up and smoked and talked in low voices. Finally the question was asked: ‘do you think we’ll get out of here alive?’ Penny said, ‘I dont think so.’ And there was silence.” By the 13th of December, the 7th Rajputs of the Indian Army under Lieutenant Colonel R. Cadogan-Rawlinson, the last Commonwealth troops on the mainland, had retreated to Hong Kong Island. The same day, the Japanese hoisted their flag over Kowloon. A demand for surrender was made and rejected.

(Japanese Artillery firing from the hills at Hong Kong)

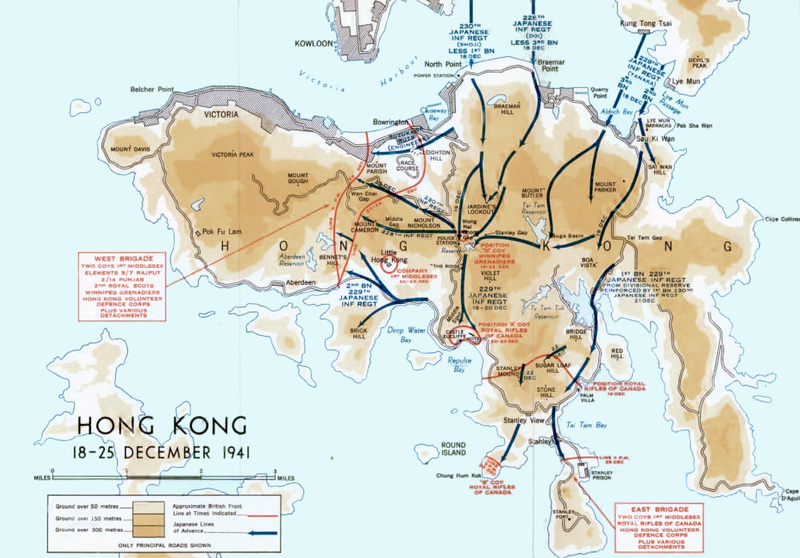

Maltby organized the defence of the island, splitting it between an East brigade and a West brigade. The Royal Rifles went into the East Brigade with the Rajputs, under Brigadier Wallis; the Grenadiers, with signals, the Punjabs and Royal Scot, into the West Brigade under Brigadier Lawson with HQ at Wong Nei Chong Gap. The Middlesex machine guns were to cover the coast from pillboxes. Morale was high among those who had not met the enemy. On the 15th of December the Japanese began bombardment of the island’s north shore and made their first attempt to gain a foothold. They were beaten off, with a Royal Rifles platoon getting in the first shots. The Japanese were actually behind schedule, and getting impatient. On the 17th demands for surrender were made again, and went unanswered. On the 18th the Japanese fired another barrage, point-blank across the harbour, targeting the area leading up to the Wong Nei Chong Gap. 7500 Japanese troops crossed the water not long after and landed on the island’s north-east side where the barrage had been directed. They came across in boats of all shapes and sizes, makeshift rafts, some apparently swam across. This time they held their foothold, although the force put ashore was unable to advance far due to a lack of effective leadership, their casualties were relatively light. The Rajputs and Middlesex manning the pillboxes on the beaches at least did as much damage as could be expected before they were overrun.

(Canadian troops on Hong Kong Island, manning a Bren gun position)

A Winnipeg Grenadier described the assault for Williams book:

“They came running ashore firing from the hip. The waves were about 30 or 40 men each, and there was nothing we could do to stop them. All our machine gun fire and limited artillery seemed to do was speed them up.”

Pre-war tactical doctrine fouled things up even more than was necessary. In the conviction that any attack must come from the south, from the sea, most of the island’s guns were facing the wrong direction. Was this merely a feint to cover a landing from the south? Wait till daybreak, some advised, then we’ll clear them out. The Japanese weren’t waiting for the sun to come up. In noiseless rubber shoes, they fanned out east, west, and south. To try to plug a gap around Jardine’s Lookout, a company of the Winnipeg Grenadiers was thrown in. Its platoons were split up. One, under a Lieutenant Brikett, was to cover the front from the Lookout’s summit. Of theri wild night in rain and darkness, Sgt. Tom Marsh recorded:

“We had been told to stay where we were for the night and report at Wong Nei Chong Gap in the morning. We had settled down when orders came to occupy the Lookout, about a mile away. Lieutenant Brikett had a Volunteer, a militiaman, as a guide. Although we were unaware of it, the Japs had already passed our destination and we were walking right into the middle of them. We reached a pillbox occupied by Hong Kong Volunteers. They tried to dissuade Birkett from going on because the enemy were all around, but he decided to carry out orders.”

They came under enemy fire, and became pinned down not long after continuing forward. The unit responded with Bren and tommy gun fire. Trying to supress the Japanese enough to fall back or move anywhere other than where they were. Mortar fire soon followed; chips of rock and bullets flying through the air. Confusion was intensified by the darkness. Patrols criss-crossed each other. Lieutenant Corrigan and his men ran flush into the enemy. By the light one bursting flash, Corrigan suddenly saw a Japanese officer rushing at him, waving a sword. he caught the blow with one hand and with the other grabbed the sword, wrestled the officer to the ground, and killed him.

Meanwhile, to the east, the Royal Rifles were strung out along a 15-mile line from Lye Mun Passage south to the Stanley Peninsula. They were already exhausted from a round-the-clock alert.As the Japanese struck through the Rajputs, virtually wiping them out, they ran into the Rifles’ C Company, sent in to defend Sai Wan Hill under Maj. W.A. Bishop. The company drove the enemy off the slopes but could not take the crest. For three hours a seesaw battle raged till the Canadians wred ordered back to avoid encirclement. At the same time, other Rifles were trying to prevent the Japanese from seizing 1700-foot Mount Parker or to evict them positions they had reached. One entire Rifles platoon and two sections were trapped and either killed, wounded, or captured.

When dawn came, the Japanese were on the summit of Mount Parker. The Rifles and what else was left of the East Brigade were ordered to withdraw south to occupy a line across the Stanley Peninsula in the vicinity of Stanley Mound, to concentrate for counterattacks. The Japanese soon cut them off from the Grenadiers and the rest of West Brigade. William Allister had spent part of his first night at West Brigade HQ at the Wong Nei Chong Gap.

My diary: “Our captain knew we’d be trapped. He left four men to keep communications going then told the rest of us to start hoofing it. Where to? Anywhere, anyway. At first we took the radio sets but later gave up and smashed them. We stumbled through the dark and rain, challenged by nervous sentries, and got lost in the hills. Ended up in a wrecked car trying to sleep until dawn. A the first gray light firing started all around us. Couldn’t find any Canadians so we joined up with an English officer. Killed my first Japanese in that firefight. Three of them. Often wondered about how I would feel about killing men. Felt nothing, just numb with fright and exhaustion. We were encircled and had to run in front of their machine guns to get away. I’ve never known such terror.”

“Everything got mixed up. You’d find yourself under a different officer. We didn’t know where anyone was. We didn’t know D Company was supporting Brigade HQ from our left and when fire came from there we returned it. We were actually engaging our own men.”

(Map of the Battle of Hong Kong)

Other Grenadiers were fighting desperately around the Lookout and Mount Butler. A platoon under Lieutenant French had stormed Mount Butler but had been driven back, its officer wounded and later killed. Then A company, under Maj, A.B. Gresham, was ordered to clear the two hills. It was split up and those under 42-year old CCSM. John R. OSborn reached Mount Butler and took it at bayonet point. They held for three hours. At last they were driven back toward Wong Nei Chong and, along with other elements of A company, were encircled. No amount of personal bravery could save this hopeless situation. They were soon overrun. In the other group from A company Gresham and others were killed, the rest wounded or taken prisoners. The enemy began pouring through the Gap. Brigadier Lawson’s HQ was cut off and he was trapped. An attempt to relieve him proved fruitless. As the enemy lobbed grenades down the air vents, bodies piled higher and higher on the pillboxes. One group of 12 decided to attempt a break out. Seven were cut down, but the other five reached cover and held off the enemy until nightfall. Then they crept through enemy lines and rejoined their own forces. At 10 AM Brigadier Lawson telephoned General Maltby that his HQ was surrounded and he was going outside to fight it out. He was killed not long after that.