The Pittsburgh Press (April 4, 1943)

Allied forces must retake the Burma Road and rebuild the Burma-China railway in order to come to grips with the Japanese on a great scale. The Allies have blasted part of the Burma Road – and it may take a year to rebuild it when – and if – it is retaken.

Reconquest of Burma a tough job

By A. T. Steele

Almost a year before Pearl Harbor, Arch Steele, of the Chicago Daily News foreign staff, took a trip into Japan and dug up startling facts about Tokyo’s plans against the United States. Then, to avoid censorship, he slipped back into China, and filed his now-famous series on “Japan Takes Aim.”

Since then, Mr. Steele’s accurate and uninterrupted war coverage has carried him into many battle zones – including Russia’s. And now – back in the United States for the first time in four years – he has written a fact-filled series on the task that faces us before we can come to final grips with Japan. The following is the first article in the series.

It’s no secret – but it’s a fact few Americans seem to realize – that a grim, heartbreaking phase of preparation still lies ahead of us before we can take the offensive on a major scale against the continental strongholds of the Japanese Army in Burma and China.

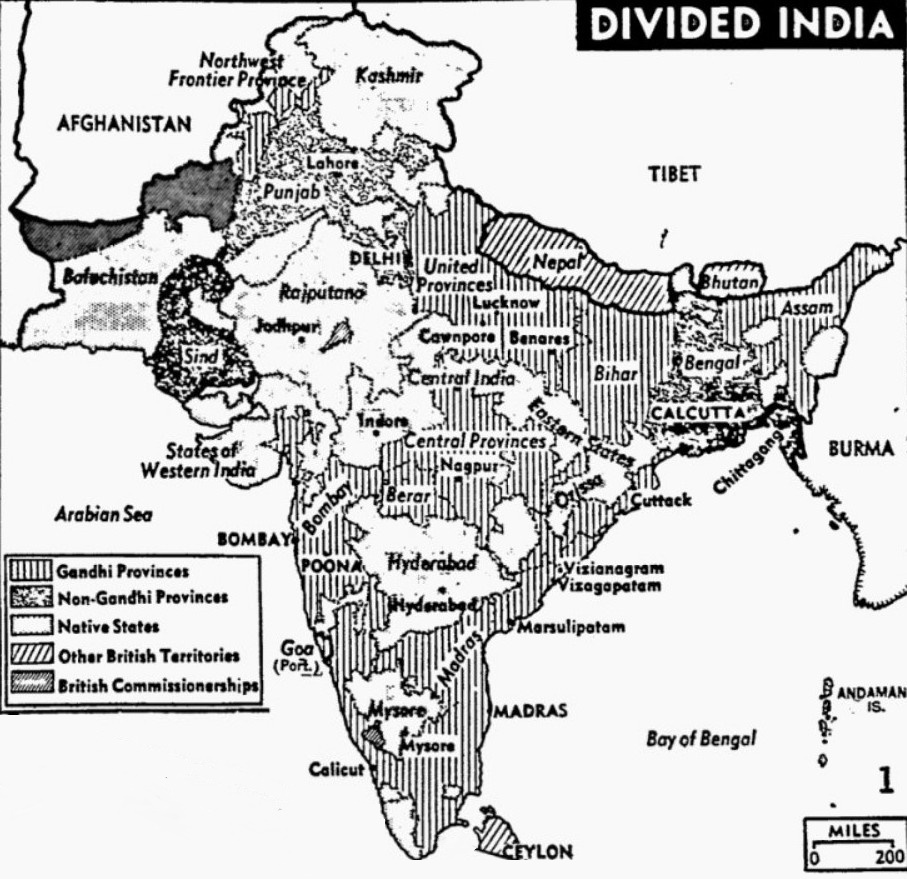

The difficulties our Anglo-Indian allies have run into in this drive against the Burmese port of Akyab – a pinpoint on the map of Asia – show what I mean. That action is, in effect, a laboratory experiment preliminary to the much bigger operation of the future. It has already taught us valuable, if painful, lessons.

The seesaw Akyab battle has demonstrated that the reconquest of Burma, which is the only key to the relief of blockaded China, will be more difficult than some Allied observers had thought.

It has shown that the Japanese are powerfully entrenched, that they cannot be rooted out without smashing superiority in armament, and that they have no intention of giving up any of the invaded territory without a struggle.

Snipers everywhere

The British-Indian force started the Akyab push with marked superiority of numbers but this advantage was quickly nullified by atrocious problems of transportation and supply through dense jungles and mazes of interlocking waterways. Snipers were everywhere – at front, side and rear.

The advance slowed up to a standstill when heavy Japanese reinforcements were brought in and began counterattacking. The British have, however, attained one important end. They have neutralized Akyab as an advance base for Japanese raids on Calcutta and other important centers in eastern India. Japanese bombers must fly farther to reach these bases, and with less protection.

The big show in Burma will require more planes, more shipping and more heavy arms than are now available for that theater. Allied military men in Asia are impatiently awaiting the successful completion of Allied offensive operations in Africa. They are hopeful, but by no means certain, that the expulsion of the Axis from Africa will release enough shipping and enough material to make an all-out offensive in Burma practical.

Helped Egypt

They are, at least, sure that once the African problem is solved, the flow of materials to Asia will increase. Africa has cost us heavily in Asia. It is well known that on various occasions in the past, military supplies en route to Burma and China have been diverted to Egypt and Libya to meet critical emergencies. Sidetracked American airplanes earmarked for India helped, for instance, to save Cairo, and participated in the subsequent drive on Tripoli.

But don’t think for a minute that Allied generals in India and China are just sitting out there twiddling their thumbs. In India, recruits for the Indian Army are still being enlisted at the rate of more than 60,000 monthly. Better than one million Indians are under arms.

Great numbers of the more-experienced Indian troops are stationed in the Middle East and Africa, where they have proved their mettle. Much is expected of the hundreds of thousands of raw soldiers and officers taken into the Indian Army since Pearl Harbor. But as a large proportion of them have been drawn from the non-martial races, and as they have yet to be tested in the fire of battle, it is not possible, now, to assess their fighting qualities.

Highway built

Besides recruiting and intensive training of Indian troops in jungle warfare, other important preparatory steps are being taken in India for the big push. Military highways are being built through the buffer or roadless forests and mountains on the Burma-India frontier, behind which the Japanese have established their forward defenses. This means that when the order is given to march, it will be possible for the Allies to move up troops and supplies swiftly to the line, at least, of the present front. Moreover, the network of new airdromes in eastern India is being constantly improved, enlarged and added to.

Of course, Burma is still 1,000 miles from the main force of the Japanese Army, far to the North, in China and Manchuria. But it is an outer gateway we will probably have to crash if we are to come to grips with the Japanese enemy on his home grounds and if we are to give China the effective material help she had earned and desperately needs.

There is only one other better avenue of attack against the Japanese Army, and that is through Siberia. If, after Hitler’s downfall, the Russians join us in the Far Eastern conflict, the smashing of Japanese military power will be greatly accelerated. We could then strike Japan at the seat of her strength. We could invade Manchuria. Without Manchuria – continental base for the Japanese Army and source of most of Japan’s basic raw materials – Japan could not go on.

Russia uncertain

But who can be certain that the Soviet Union will enter the Pacific War, even when Germany collapses? We can hope, but we cannot be sure. Our strategy cannot be based on possibilities. It has to be founded on certainties.

There is an element among Allied military men which refuses to take China very seriously. This group feels that the reconquest of Burma is not an urgent problem and that our help to China need only be of a token nature until the main job of crushing Hitlerism is completed. This is not, incidentally, the view of Lt. Gen. Joseph W. Stilwell, commander of U.S. Army forces in China, Burma and India. Gen. Stilwell is itching to get on with the job of recapturing Burma as soon as it is practical to attempt it.

The dry season in Burma is nearing its end, and the chances for any effective action in the short period remaining are very slim indeed. The monsoon rains will then probably paralyze the Burma front until October, when another dry season will set in.

Just a beginning

The reconquest of Burma will only be the beginning of the solution of the problem of striking at the Japanese arm. The task of repairing and restoring traffic on the Burma Road will itself be a formidable one. Parts of the road, blasted away to impede the Japanese advance, will have to be rebuilt. Big bridges will have to be reconstructed. This will all take time.

And the opening of the Burma Road alone will not solve China’s supply problem. It will be necessary to complete the Burma-China railway, which was 40% finished when the Japanese invaded Burma. This will take six months to a year – perhaps more. The Burma Road and Railway, together, would greatly relieve the strain on China and would make it possible for us greatly to intensify our aerial and military pressure on the Japanese Army, but they would not carry sufficient tonnage, for the final knockout offensive.

Before that is possible, the Allies will be obliged to open other channels of supply into China. However, the restoration of the Burma Road will facilitate enormously the recapture of Indochina and perhaps a port or two in South China, which could be used as subsidiary lines of entry.

Then, and not until then, will we be ready for the real big show, to deliver a truly decisive blow.