The Longest Siege - Robert Lyman

Tobruk , Peter Fitzsimmons

en.wikipedia

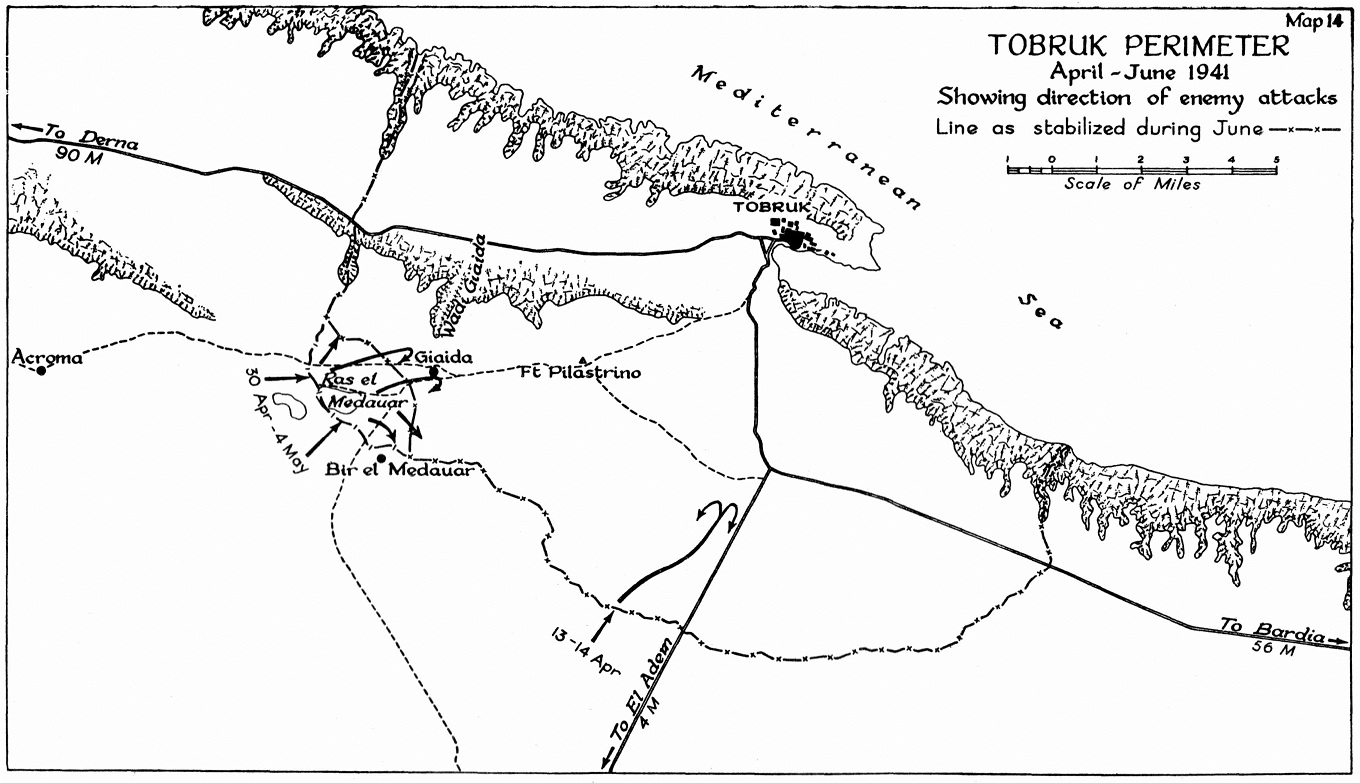

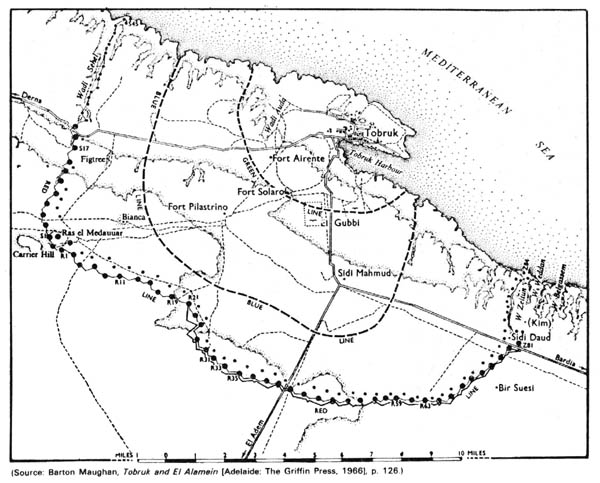

By the end of April 1941 , It was clear from the continued pressure against the perimeter and from aerial reconnaissance that Rommel was preparing another attack on Ras el Medawar to pierce defensive perimeter from southwest and capture Tobruk. Frantic efforts were made by the Australians in the western sector to re-sow minefields, replace broken barbed wire and restock with ammunition for the coming onslaught as the Luftwaffe daily pounded the forward areas between Point 209 and Fort Pilastrino. Despite the setbacks in mid-April Rommel was still confident of a rapid victory – if he had sufficient German troops. Writing to his wife Lucie on the 23rd he recorded, ‘Once Tobruk has fallen, which I hope will be in ten days or a fortnight, the situation here will be secure. Then there’ll have to be a few weeks’ pause before we take on anything new.’ But two days later Rommel admitted his nervousness: ‘I shan’t be sorry to see more troops arrive, for we’re still very thin on the long fortress front. I’ve seldom had such worries – militarily speaking – as in the last few days.’ However, Axis troops and equipment were now rapidly concentrating behind Acroma, and by the end of April Rommel had 120 tanks available to launch what he was certain would be the final, decisive attack on Tobruk.

The British likewise rushed reinforcements forward during April -by sea. Private Jack Senior of the Royal Signals arrived with a group of fellow signallers in an ex-North Sea trawler in the days before Pritt-witz’s first attack on the perimeter. On the voyage from Alexandria he manned a Bren gun in case of attack by enemy aircraft despite complaining that he had never been trained on the Bren. ‘Now is the time to learn,’ came the response. As they arrived off Tobruk and entered the harbour they passed floating bodies, some face up staring lifelessly into the sky. A beached Italian cruise ship – the Marco Polo – belched black smoke. The trawler dodged around other wrecks in the harbour before disembarking the signallers, who then travelled by truck to a wadi on the west of the town. Settling down for the night on the rocky ground, they lay on their backs watching a high-level bombing attack on the harbour they had just left before falling fitfully asleep.

As the day dawned they were woken by shouts and a number of shots. A voice bellowed to them to report to a bell tent on the beach and to take with them what water and food they could grab. With no idea where either the beach or the tent were, they nevertheless stumbled after some others and found where they had been told to report. A Coldstream Guards sergeant major met them, issued them each with a bandolier of fifty rounds, shook hands and wished them the best of luck. They were dumbfounded. Finding his voice, Jack stammered out that they were Royal Signals personnel and had been sent to Tobruk for a ‘special job’. ‘Yes, that’s right,’ replied the Guards NCO. ‘You are now Royal Signals Infantry and your special job is to stop the Germans from breaking into Tobruk.’ A few minutes later their transport arrived: one weather-beaten Bren carrier belching smoke and a battered Italian ambulance. After thirty minutes bouncing across the rocky ground they reached El Adem beyond the southern perimeter, joining a number of Guardsmen in a wide antitank trench acting as a forward lookout post for a German column, which was expected at any moment. Their instructions were simple. ‘When you see us running like hell, try to overtake us and get back inside the perimeter.’ Fortunately for the dazed signallers, they were withdrawn well before any Germans appeared.

On 19 April 1941 Lieutenant Alexander McGinlay, reconnaissance troop commander of D Squadron, 7th RTR, was part of one of the first tank crews to be taken into Tobruk on one of the new and secret tank landing craft – known as A Lighters to disguise their purpose. They were flat-bottomed, and discharged their cargo via a bow ramp lowered onto the beach. Loading up at Mersa Matruh, each A Lighter conveyed three or four Matildas to Tobruk:

“We went in line ahead, and the first one ran foul of one of the many wrecks in the harbour. As number two in line, and having a fair idea of a good spot to beach, which was just under a huge crane, I helped guide our tank landing craft in, and we were off like a flash, headed up the three escarpments, guided into our leaguer positions [near Pilastrino] by members of the 6th RTR who had been there some weeks. We were shelled but not damaged, and soon settled in. We could not dig in, being on a very rocky ridge. We camouflaged our tanks as best we could and scraped shallow holes for ourselves. Many were the varied hideouts over the months which we thought up. Bits of wood laid across rocks, canvas sheeting over them, rocks on top of that, and there we were, completely hidden from the air.”

They only had days to familiarize themselves with the battlefield. In the late afternoon of 30 April Rommel’s expected onslaught against the western defences at Ras el Medawar began with an hour-long aerial bombardment of forward posts by two separate waves of twenty-five Stukas, followed by the heaviest artillery barrage the Australians had yet experienced. Four miles of this part of the perimeter were held by a single Australian battalion, the 2/24th, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Allan Spowers. Morshead had a second battalion in reserve for counter-attacks, together with the support of three artillery regiments (51st Field, 1st RHA and the South Notts Hussars) as well as the Tobruk Tanks with a mixture of cruisers, newly arrived Matildas and armoured cars. Morshead’s greatest problem was that he did not know whether this was the sole assault or if another penetration was to be attempted at El Adem. As the Stuka and artillery barrage came down, blotting out the late-afternoon sun with clouds of dust and debris, German troops of the newly arrived 2nd Machine-Gun Battalion, 115th Artillery Regiment, 104th Rifle Regiment and 33rd Engineer Battalion advanced to the perimeter, clearing lanes through the minefield and directing such heavy fire against the forward Australian positions that within forty-five minutes of the initial attack a successful breach had been achieved. Under cover of the bombardment small groups of German soldiers rushed through, crouching in the distinctive way troops do when they advance into the unknown, weapons clutched in clammy hands, stomachs knotted, faces scanning the ground ahead through the dust and smoke for their first sight of the enemy, ears attuned to the final screaming seconds of an incoming mortar or artillery shell. Behind the front waves, through the cleared lanes in the minefield (the Australians called the process of clearing a minefield delousing), rumbled the menacing panzers.

Back in Tobruk Major John Devine recalled in his diary, ‘A day of great anxiety and alarms. All roads were blocked, and all military police issued with Molotov cocktails, made out of old Recoaro mineral-water bottles filled with petrol. Even the air raid siren was stopped so as not to reveal the position of the town. All day the artillery thundered, and as I write now in the evening everything shakes to a distant rumble.’ In the docks Private Parish described the atmosphere around the harbour as a ‘flat spin’. All the dock personnel were given rifles and organized into infantry sections for the defence of the harbour. Air attacks continued without let-up against the harbour, artillery and anti-aircraft positions, an anti-personnel bomb falling on 1 May between John Kelly’s trench and his tent, riddling his greatcoat with shrapnel.

The 104th Rifles, part of the 15th Panzer Division, had arrived by air at Benghazi over the previous week. They had left their barracks in Baumholder in the Rhineland Palatinate in a thick snowstorm only days before, exchanging blinding snow for choking sand. Setting off on foot from the dusty ruins of Acroma, the troops of the 115th Infantry Regiment marched, heavily laden with machine-gun ammunition and grenades, towards the clouds in the distance thrown up by the artillery bombardment. Paul Carell described the attack: “They passed the first smashed barbed-wire entanglements and saw the first traces of tank tracks. The noise of the battle grew louder. Ahead of them clouds of dust thrown up by the shell bursts. A wall of dust marked the front line . . . They saw the first dead British [sic] soldiers in this theatre of war; their faces had been swollen out of all recognition by the heat. The corpses were in such an advanced state of decomposition that the uniforms had burst. Three or four Australians lay close together. They must have been killed by a machine-gun burst.”

“Soon they met the first German soldiers returning from the front line, covered with filth and mud. A sergeant major staggered past. He was bleeding from the shoulder. The first shells fell close to them. Take cover! In short sharp rushes they made their way forward. The battlefield was covered with dead. They could not have been lying there very long for the bodies had not yet begun to swell.”

New to the Tobruk battlefield, as they advanced into the Australian fire the German soldiers looked in vain for signs of entrenchments and pillboxes of the sort they had seen in France. They did not realize until they fell in or went past them that the Tobruk defences had been blasted deep into the rock and were flush with the ground. The concrete-reinforced positions were extremely difficult to locate let alone overcome, and had been constructed by the Italians for all-round defence. At the breach the German infantry and combat engineers peeled off north and south and started to work their way along the perimeter, attacking each sunken Australian post as they came to it.

The 1st Battalion of the 104th Rifle Regiment began their attacks around Point 209 at 2 a.m on 1 May. The battalion’s combat engineers were ordered to take R6. Crawling forward on their bellies as quietly as possible the men badly cut their knees and elbows on the rocks. The plan was that when Lieutenant Friedl Schmidt fired a white signal flare, a barrage from 88s, field guns captured from the French months before and a huge 21-centimetre mortar would fall on R6. However, when Schmidt fired his flare, watching it soar into the air before slowly falling away into the darkness, he provoked not the German bombardment he was expecting but a fusillade from the Australian defenders only yards to his front. Bullets ripped through the night and grenades exploded around the engineers in a blitz of light and sound, the Germans afraid even to lift their heads. The diminutive and popular Private Sigrist was shot through the throat; amazingly the bullet exited his neck without doing any more damage than making a hole, and the young sapper was back on duty a week later. But that night they could make no headway against R6, and before first light, under cover of a thick dawn fog, they crawled back the way they had come, pulling their wounded behind them, Australian shots directed at the slightest sound.

German losses that night were heavy. Lieutenant Cirener, winner of the Knight’s Cross in France a few months before and a company commander in the 33rd Engineer Battalion, was killed. The 104th Rifle Regiment suffered 50 per cent casualties. The CO of the 1st Battalion, Major Faltenbacher, was mortally wounded in the stomach, and the commanders of the battalion’s four rifle companies were also wounded, one mortally. The Australians had refused to be intimidated by the force of the German assault, and doggedly held their ground. But German infiltration tactics meant that each Australian post had quickly found itself cut off from its neighbours and as the fighting continued throughout the night neither side had a clear idea of the overall situation.

During the night Spowers counter-attacked in an attempt to regain control of Point 209 and make contact with any of his troops still on the now cut-off rise. The darkness, smoke and confusion made it difficult to know precisely where the enemy were, preventing the British artillery from providing accurate counter-fire. Consequently the infantry counter-attacks made little progress. The breaking dawn and lifting fog on 1 May revealed at least sixty Axis tanks on Point 209. Seven Australian posts around the rise had been overwhelmed during the night and a German salient a mile and a half wide established. The Axis were now pouring in reinforcements and supplies from Acroma to enable them to punch through the remaining defences into Tobruk. That at least was the plan.

At first light at least forty of these German and Italian tanks began to roll eastwards in the direction of Tobruk along the Acroma road in a repeat of the Italian attack of 15 April. In their path was a thin minefield located forward of the rearmost Australian company guarding the crossroads at Bianca, hastily laid on Morshead’s instructions following the Italian breach two weeks before. In addition there were the twelve First World War 18-pounders of the 51st Field Regiment and the twenty-four 25-pounders of the 1st and 107th RHA, which had been firing all night, the gunners exhausted and the guns hot from incessant use. A few Australian 2-pounder anti-tank guns in the north and some belonging to 3rd RHA in the south were the only purely anti-tank units in the threatened area. Around Pilastrino were grouped the Tobruk Tanks: the cruisers of 1st RTR and the 3rd Hussars, the few Matildas of 7th RTR brought up by sea and the ancient armoured cars of the King’s Dragoon Guards.

Setting off from Acroma at 4.30 a.m. Lieutenant Joachim Schorm, leading his troop of four Mark IVs of 6 Company of the panzer battalion commanded by Major Hohmann, drove through a barrage of artillery fire at the perimeter breach. With the other tank companies detailed to deal with continuing Australian resistance on both Point 209 and the perimeter posts to the south, Schorm’s company continued east as the vanguard of the advance into Tobruk. Soon afterwards he heard over the radio that his company commander’s tank had struck a mine. Then an explosion rocked his tank, and ‘things happened suddenly. Artillery shell hit? No? It must be a mine. Immediately send a radio message: “Commander Schorm on a mine. See if you can turn around in your own tracks.” Five metres back. New explosion – mine underneath and to the left.’ The entire company had struck Morshead’s hastily laid minefield. Leaving his disabled panzer, Schorm climbed aboard another. ‘Back through the artillery fire for 100 metres. Wireless order: “Panzers are to retire behind ridge.” The men of the mined tank are all right. Enemy is attacking with tanks, but must be put to flight. Retire carefully . . . Nine Mark IIIs and three Mark II tanks of the company have had to abandon the fight owing to mines. Of course the enemy goes on shooting at us for some time. I move back through the gap with a salvaged tank in tow.’

Captain Peter Gebhardt, commanding the rearmost Australian company of the 2/24th Battalion overlooking the minefield, watched with relief as the twelve German tanks of 6 Company – together with four from another – were brought to a shattering halt. Relief was immediately tinged with frustration as those tanks not destroyed were recovered by the Germans and dragged to the rear. The only weapons Gebhardt had to counter this activity – at a range of about 500 yards -were his Lee Enfields and a single ineffective Boys anti-tank rifle. Not having anti-tank guns covering the landmines was a serious mistake. Nevertheless the minefield, combined with British artillery, had by 9 a.m. destroyed or disabled some twenty tanks across the German salient and decisively thwarted Rommel’s attempt to smash his way into Tobruk. As during the El Adem battles two weeks before, the German tank men were astounded by their Australian opponents. They had expected them to run when confronted by tanks and were thoroughly disconcerted when the Diggers fought back with grenades and bayonets. Their tenacity had a significant effect on Rommel’s plans as, instead of concentrating to break through en masse, the German tank crews time and again peeled off to deal with the widely scattered pockets of resistance across the salient. This dissipated the panzer effort, negating its supreme virtue – concentration of force.

In the meantime the remainder of Major Hohmann’s panzer battalion was busy fighting through the Australian posts to the south of Point 209. Groups of four or five tanks attacked each in turn. The tanks were followed by parties of forty or fifty German infantrymen, who would make the final rush on a trench with sub-machine guns, bayonets and grenades. The first to fall was R1, which Major Hohmann reported was occupied by twenty-four Australians. ‘In the course of this operation,’ he wrote, ‘Obergefreiter Schaefer displayed conspicuous courage by leaping into the fortified position with hand grenades and taking several prisoners.’ The fighting was fierce. When unsupported by tanks the German infantry were cut down in their scores by well-hidden Australian rifles and machine guns. The ground was too hard to dig slit trenches to shelter from the artillery fire, which fell like rain, and whenever heads were raised above the rocks behind which the attackers found shelter, they were shot at by the Australians. To the Germans’ discomfort the Australians were extraordinarily good shots. During the day the men were forced to lie still in whatever shallow protection they could find for fear of taking a bullet, eating and carrying out all other necessary activities only when darkness fell.

Over the following three days the battle degenerated into a struggle by small groups of desperate men for isolated pockets of rocky desert. Few of the defenders knew what was going on elsewhere on the battlefield but fought on resolutely, counter-attacking fiercely when the enemy managed to take all or part of a bunker, refusing to give in. Signaller Frank Harrison spoke to a Digger on 5 May. Of course he had been scared, the Australian replied when asked, ‘scared to bloody death, mate’. His strongest memory was of not knowing ‘what the 'ell was going on and who the 'ell was doing it’.

At R4 Corporal Bob McLeish and his colleagues in the 2/24th were forced to defend themselves as best they could. As the Germans drew closer the Diggers opened fire, which forced the infantry to go to ground but did not stop the advance of four tanks:

“Their machine guns kept our heads down and their cannon blasted away our sandbag parapets. The sand got into our MGs and we spent as much time cleaning them as we did firing them, but we sniped at the infantry whenever we got the chance. Our anti-tank rifle put one light tank out of action, but it couldn’t check the heavier ones, which came right up to the post. We threw hand grenades at them but these bounced off, and the best we could do was to keep the infantry from getting closer than a hundred yards.”

Likewise, at R8 Sergeant Ernest Thurman and his shrinking band of men were able to keep up the unequal struggle because two German Mark IVs – having destroyed the 2-pounder anti-tank guns of the 3rd RHA – refused to advance across a non-existent minefield fifty yards in front of the post. ‘They raked the top of the post with machine guns and cannon, and the crews even stood up in the turrets and threw stick bombs into our communication trench. But we still kept firing at both tanks and infantry. We’d take a few pot shots and then duck before their machine-gun bullets thudded into our sandbags.’

The defenders were not averse to taking on the panzers with little more than their bare hands. Trooper Bob Sykes of 6th RTR found himself a temporary infantryman and honorary Australian in the Tobruk defences. He was awoken just before dawn on 1 May with the news that German tanks had broken through:

“I staggered out to our Morris truck while in the darkness figures were loading up: petrol, bombs, grenades, guns, ammo, the lot. After travelling a long way we came to a barbed-wire barricade – a section was slid apart and we went through. In the distance a small war was going on. Tanks were moving away from us and we went after one that seemed to be behind. It was a German tank and some of the Aussies raced off behind it and jammed steel rods [metal fence pickets] between the tracks. Petrol bombs lit up the tank; grenades and shots rang out. We swung the truck close to the tank, which was well alight, and the raiding crowd jumped aboard. We had very minor casualties but tension remained very high.”

Fighting continued south of Point 209 during the afternoon and evening. The Luftwaffe mounted heavy raids in an attempt to silence the devastatingly effective British artillery. In his diary Schorm reported, ‘Dive-bombers and twin-engine fighters have been attacking the enemy constantly. Despite this, the British repeatedly counterattack with tanks. As soon as the planes have gone, the artillery opens up furiously. It is beginning to get dark. Who is friend and who is foe? Shots are being fired all over the place, often on our troops and on panzers in front which are falling back.’ It seemed to the Germans that the Allies had so much ammunition that individual soldiers were sniped at with artillery. When Lieutenant Friedl Schmidt went to visit Lieutenant Wettengel in a neighbouring position he came under fire from a lone gun. Moving in short rushes, he dived to the ground as the whine of an incoming shell warned him that it was nearly on him. During his journey he came across a slit trench. It was occupied. Crawling over the lip he was greeted by an overpowering stench. Eyes staring skywards, the lifeless body of the regimental doctor lay crumpled at the bottom, rapidly decomposing in the desert heat.

Small groups of British tanks helped to respond to local threats, the Matildas acting as mobile pillboxes and attracting the attentions of the Stukas and Messerschmidt fighters that roamed above the battlefield. Major George Hynes of B Squadron 1st RTR narrowly escaped death when a bomb dropped by a Stuka struck the ground next to his cruiser without exploding. In the late afternoon a fierce battle near R6 took place between panzers and the Tobruk Tanks. A mixed force of five Matildas of 7th RTR and a handful of cruisers of 1st RTR, nosing forward to ascertain what positions had been captured by the enemy and what continued to be held by the Australians, came under attack first from fifteen panzers to the front. Then, responding to the radio calls of their comrades, eight more panzers emerged from the direction of the wire to the left and shortly thereafter another fourteen appeared from the north-east. ‘Jerry tanks seemed to attack us from all sides,’ recalled Sergeant Stockley of 1st RTR, pleased he was in a Matilda rather than a cruiser. ‘One cruiser was disabled and the other, because of its light armour, had to withdraw leaving us four to fight it out . . . We were hit many times, but our heavier armour saved us and we kept the Jerry tanks off until it became hard to tell theirs from ours in the half light.’ During the battle Alexander McGinlay, commanding his Matilda, felt a hard knock on his right leg:

“I thought it was my loader/operator, and yelled at him to ‘mind his bloody feet’. I should have noticed that at the same time the two cupola lids had flown open. It wasn’t until after the action, as we were rallying, that I looked down and saw sunlight streaming in on the floor of the turret. Now sunlight is the last thing one expects to see there. What had happened was that we had received a direct hit from an enemy 105-millimetre gun at very short range. The whole of the thick armour all along the side of the tank had sprung open, about three or four inches. That shows how tough these Matildas were. All we noticed was a kick on the leg from a 2-pounder shell dislodged from its rack and a puff of wind.”

This tank engagement was a victory for the Germans, but they failed to exploit it. Unaware of the devastation wrought on the British and that the 1st and 7th RTR tanks were entirely out of ammunition, the Germans broke off the engagement at last light, withdrawing back through the breach to replenish and refuel at Acroma. They could have continued on to Tobruk unopposed, had they continued their advance. But Rommel’s armour had also suffered that day. German and Italian tank losses were severe: the 5th Panzer Regiment had gone into action with eighty-one tanks on the morning of 1 May and ended 2 May with only thirty-five; most had been destroyed or disabled by mines. Many, however, were recovered from the battlefield, repaired and pressed back into service.