26 October 1942

In London, an intelligence planning group headed by Cdr. Ewen Montagu, a King’s Counsel and leading member of the bar, discusses a highly unusual development. A British flying boat going from Lisbon to Gibraltar crashed in September, washing up bodies of passengers and crew on a Spanish beach. Among the bodies is that of Lt. J.H… Turner, a Royal Navy postmaster, carrying a letter from Gen. Walter Bedell Smith to Gen. Sir Henry Mason-MacFarlane, Governor of Gibraltar, regarding Ike’s future headquarters there. The letter has been returned, still sealed in the coat pocket. The Spaniards claim the water opened the envelope’s four seals. The writing is clearly still legible. Nobody is sure if the Germans have been given access to the letter, and if so, whether security has been breached.

Someone points out that when the British unbuttoned Turner’s jacket, sand had fallen out of the buttonhole. It had apparently been rubbed into the buttonhole while the body lay on the beach. No agent would replace the sand when re-buttoning the jacket. The secrets must be safe.

Montagu makes a suggestion. What if the British deliberately send a body ashore to Spain in a uniform, carrying faked documents? That could send the German high command into a tizzy that could, in turn, divert German troops from a major invasion. Montagu’s suggestion goes up the chain of command. It will become Operation Mincemeat, better known to the public as “The Man Who Never Was.”

The Germans don’t know it, but they have missed a major chance to determine the Allies’ next move. Indeed, the are overwhelmed with information. Many German intelligence officers believe the Allies will invade Dakar, using Brazil, the newest addition to the Allies, as a base. From there the Allies would then move overland into Morocco. This belief is supported by reports from the Portuguese ambassador to Brazil on large quantities of American troops and equipment in Brazil. This material is actually for the Takoradi air supply route to Egypt.

Another report comes from a source known for its excellent intelligence system: the Vatican City. Catholic officials in the Vatican who sympathize with Germany tell Nazi and Italian agents that the Allies are heading for Dakar.

Other clues come from German spies, who gain their information from junior Allied soldiers and civilians, or from reading newspaper articles by armchair strategists. German spies buff up these questionable reports by attributing the results to “observers” or “well-informed circles here.”

The Germans are also fooled by Allied intelligence, which has control of nearly every Axis spy in Britain. The “Double Cross System” feeds the Germans endless lies and spurious rumors, suggesting that the Americans and British will soon invade Norway. Or Denmark. Or Holland. Or France. Or all of the above.

To keep the Germans believing this rubbish, the “Double Cross” controllers add real, but minor information to the “carillon.” These tidbits include the 28th Infantry Division having a keystone as a symbol, or that a clock in Tidworth is two minutes slow. The Germans turn this information over to their propaganda broadcasters, like “Axis Sally” and “Lord Haw-haw,” who use them in their diatribes. Allied soldiers, listening to these broadcasts, are amazed at how the Germans can have such accurate information, and see “spies” everywhere. The Allied soldiers don’t realize the broadcasts are just part of greater deceptions.

Meanwhile, the Germans manage to work through the vast array of lies to learn some truths. The Abwehr reports the Allies readying convoys in Britain, then putting to sea.

The only Axis intelligence people who figure out the truth are the maligned Italians. They believe the Allies will invade Morocco.

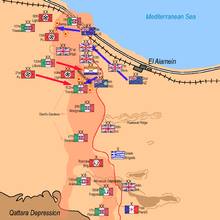

At midnight, the Australian 9th Division opens up with 16,000 rounds of 25-lbr. ammunition on the German 125th Regiment. The 2nd/48th Australian Battalion heads out at midnight - one company in Bren gun carriers - and arrives at Point 29 dead on time. They find the defenders stunned and exhausted from the artillery bombardment. The Australians take the hill in two minutes.

The rest of the Australian attack does not go as well, as the German defense is as tenacious as ever. But the Australians gain ground and take 300 German prisoners and count at least that many German dead lying on battlefield.

South of the Australians, the 51st Highland Division struggles on, supported by Valentine tanks. Heavy bombardment demolishes three German 88mm guns, and the 5th Black Watch finally takes the Oxalic Line.

7th Armoured Division and 51st Highland Division argue over attack routes in the same sector. The tankers claim to be further west than they actually are. The two division staffs bicker over maps, forcing Montgomery to order the troops to fire flares at a specific time during the day. His surveyors will use the flares to establish cross-bearings. The results embarrass 7th Armoured.

Meanwhile, 10th Armoured Division finally moves out of 2nd New Zealand Division area just after midnight, swinging into the 1st Armoured Div. area. 10th Armoured Division men go without sleep for the third straight night.

13th Corps’ infantry attacks as well. Two battalions of 69th Brigade move fowrard. The 6th Green Howards take 45 Italian paratroopers of the Folgore Division POW and their objective. But 5th East Yorks come under heavy shellfire, lose 100 men, and have to withdraw to their start line.

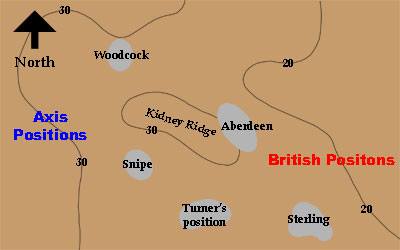

At 5 a.m., Rommel hops into his command car to personally lead the Axis defense. He learns that the British have hurled 500 artillery rounds at him for every shot his guns have sent over. He drives to the front, where 15th Panzer and Italian Littorio Division tanks have attempted counterattacks on Kidney Ridge, only to be slaughtered by well-placed British anti-tank guns , losing 26 panzers and five Italian tanks. Rommel summons the 90th Light Division and Luftwaffe 88mm AA guns to help. It takes the German 90th Light Division all morning to move up and get in position.

Meanwhile, the Australian advance continues, backed by two brigades of British tanks. The Highlanders consolidate on Oxalic Line, while the South Africans and Indians anchor 30th Corps.

In the 13th Corps sector, the fighting dies down as the Germans withdraw 21st Panzer Division and Ariete ArmoredDivision to head north into the main battle. (they finally realisedon thirds day of batle that , British movements in south were deceptions to divert their reserves. The success of Operation BERTRAM is appearent)

All day long, the British maintain heavy shelling of the Axis positions, while squadrons of fighters and bombers hammer the Afrika Korps. The Germans are almost unable to shoot back. When the Italians counterattack, they send in the old - M13 tanks - and the new - Semovente self-propelled guns - against the 2nd/13th Australians. The Australians call down heavy shelling that turns the Italians away.

The Italians regroup and try again, and the Australians call in RAF A- 20 bombers, which pulverize the enemy with 500-lb. high-explosive bombs.

Other British units find the same. 51st Highland Division and 2nd New Zealand Division spend the day under random shelling. 24th Armoured Brigade’s tank crews even get some sleep.

Rommel sends 90th German Light Division forward against Kidney Ridge personally at 3 p.m., and comes under heavy fire. The bombardment reminds Rommel of the Western Front in 1917. The 90th Light’s men dig in wherever they can, their assault stopped, in an inferno of noise and smoke however under heavy British shelling their casaulties are high .

The British put their advantage of having broken the German Enigma coding system to good advantage. The British read the German communications, and send air strikes to disperse Axis forces as they concentrate, disrupting counterattacks.

Italian and German dive-bombers (including Italian-manned Ju 87 Stukas) try to interdict the Allied supply line. The famous Stukas are intercepted by something new in the desert, Spitfires. More than 60 of them sweep into the Luftwaffe formations, scattering the Stukas. Italian bombers jettison their loads over their own lines and scurry home. Surviving Germans struggle to the target and fly into a wall of AA fire. 24 Axis aircraft were shot down.

Horrified by the destruction, Rommel returns to headquarters. He orders 21st Panzer Division and Ariete to head north and seal off the northward drives. Rommel’s chief of staff, Gen. Siegfried Westphal, points out that this move will consume much fuel. However, the Italian tanker Proserpina is due in Tobruk the following day with 2,500 tons of petrol, followed by the Tergesta, with another 1,000 tons of fuel and 1,000 tons of ammunition.

These ships’ loads will give Rommel an extra six days supply of fuel. Rommel notes that British armor is still poor at fighting mobile battles, but British infantry, artillery, and airpower, are doing a superb job.

That evening, Rommel radios Hitler to request more supplies, saying his army’s survival is in the balance. “We shall lose this battle unless the supply situation improves at once,” he says. But Rommel writes his wife Lucie to say that he is not despairing.

After sunset, 21st Panzer Division moves north, harassed by British night bombers. They cause very few casualties, but slow the panzers’ advance.

The British 7th Motor Brigade moves to its startline near Kidney Ridge, and stars moving 11:30 p.m.

2nd New Zealand Division and 1st South African complete the occupation of the final objective on the forward slope of Miteiriya Ridge. The South Africans take over the Kiwi front, and 2nd NZ Division withdraws to Alamel Onsol, a few kilometers in the British rear, to recuperate for the next phase of the battle. Under its charter from Wellington, 2nd NZ Division cannot be wasted in static defense. It is designated as an assault force.

On the British side of the line, de Guingand reports the casualty bill to Monty. 30th Corps has lost 4,643 men, 10th Corps 455, and 13th Corps 1,037. The price is not exorbitant, and most of the losses are the hard-working infantry. The Australians have lost about 1,000 men, the New Zealanders the same, and the Scots 2,000. Some New Zealand companies are down to 50 or 60 men. Enemy casualties are estimated at 61,000 men, 530 tanks, and 340 field guns. Montgomery says those numbers are extremely inflated.

The situation is critical. German forces are short of fuel, British tank losses are heavy (though mostly theser knocked out British tanks can be recovered , repaired and get back to battle), and men on both sides are exhausted. But Montgomery still has vast supplies of ammunition and 800 tanks. Artillery duels continue into the night.

Eisenhower drives to London with Mark Clark to brief Churchill on Clark’s journey. Churchill, a veteran of similar harum-scarum escapades in the Boer War, enjoys the story.

In the Clyde, the fast convoy of ships headed for North Africa sets sail. The slow convoy has already departed on the 22nd. 39 vessels with 12 escorts make up the fast force, while the slow group has 46 cargo vessels and 18 escorts. Among the ships in the slow convoy are three Lake Maracaibo (Venezuela) oil tankers modified to land vehicles through their bows. These are the first landing ship tanks, but they can only land M3 Stuart light tanks. Shermans and Grants are just too big to clear the openings.

As the Allied convoys move, German and Italian intelligence goes to work to figure out the Anglo-American moves. The Germans guess that the Allies are headed to relieve Malta or invade Dakar. The Italians, more realistic, suspect a threat to French North Africa, and alert their troops around Tripoli to be ready to move into Tunisia.