Resources

-Memoirs - Field Marshall Montgomery

-The Battle of North Africa , El Alamein , Turning Point of World War II - Glyn Harper

-Pendelum of War , Three Battles of Alamein - Niall Barr

-The World Arms (Readers Digest)

-Eighth Army’s Greatest Victories - Adrian Turner

-Britain’s War in Desert - David Braddock

-Howard Kippenberger , Dauntless Spirit - Denis Mclean

-Foxes of Desert - Paul Carell

-Rommel Papers - Lidell Hart

-Montgomery , Master of Battle 1942-1944 - Nigel Hamilton

-The Alexander Memoirs - Field Marshal Alexander

18 October 1942

In the Egyptian desert, the British 8th Army is preparing for its massive counterattack. A massive deception goes on at the south end of the British line, masterminded by stage magician Jasper Maskelyne and his “Magic Gang.” This group of illusionists has created a massive array of supply dumps, armor, and artillery - all of it fake. The army of wooden guns, cardboard tanks, and phony dumps is backed by specious radio traffic. Royal Engineers add to the sorcery by building a dummy water pipeline in the south, that cannot possibly be finished until a week or two after the actual attack. Rommel has fallen for this deception. The 21st Panzer Division and Italian Ariete Division are in the south, along with the Italian Folgore Parachute Division.

The Germans are worn out from dysentery, fatigue, poor rations, and supply shortages. Some of their best officers, like Gen. Frederick Von Mellenthin, have gone back to Europe - in his case due to dysentery - because of wounds or illness. The Italians are in worse shape, unwilling to undertake deep patrols. The Axis plant more and more minefields.

On the British side of the line, preparations for offensive are in full swing. 1st Ammunition Company of 2nd New Zealand Division sends 76 lorries loaded with 160 rounds a gun for the 25-pounders. Supply Company provides trucks equipped with beaters similar to drum and chain arrangements to rumble around the desert, creating tank tracks, as if a massive armored column is to roll southward.

At 22nd Battalion, General Bernard Montgomery decorates Sgt. Keith Elliott with the Victoria Cross. He tells the battalion, “A magnificent spectacle. I’ve seen you in action and on parade you’re equally good. You’ve killed Germans before and you’ll kill them again.”

19 October 1942

At Gibraltar, a two-star general of the US Army clambers aboard the British submarine HMS Seraph to embark on a schoolboy adventure. Maj. Gen. Mark W. Clark, followed by Brig. Gen. Lyman Lemnitzer and Col. Julius Holmes, joined by another Army colonel and a Navy captain, squeeze themselves and their pigskin luggage aboard the submarine, which is also jammed with a party from Britain’s Special Boat Service. Their destination is Algeria, where Clark is to make contact with Vichy French generals, and help clear the way for the Allied invasion of French North Africa.

Under its skipper, Lt. Bill Jewell, Seraph heads out at 8 p.m., and makes a surface cruise at top speed.

Montgomery addresses his officers down to lieutenant colonel in his three corps, explaining the upcoming battle and his plan. The British objective is to “kill Germans. Even the padres, one per weekday and twice on Sundays.”

Howard Kippenberger inspects 23rd New Zealand Battalion, and tells them “This is the turn of the war and the greatest moment of your lives.” 23rd Battalion is to lead the New Zealand attack. The troops cheer.

20 October 1942

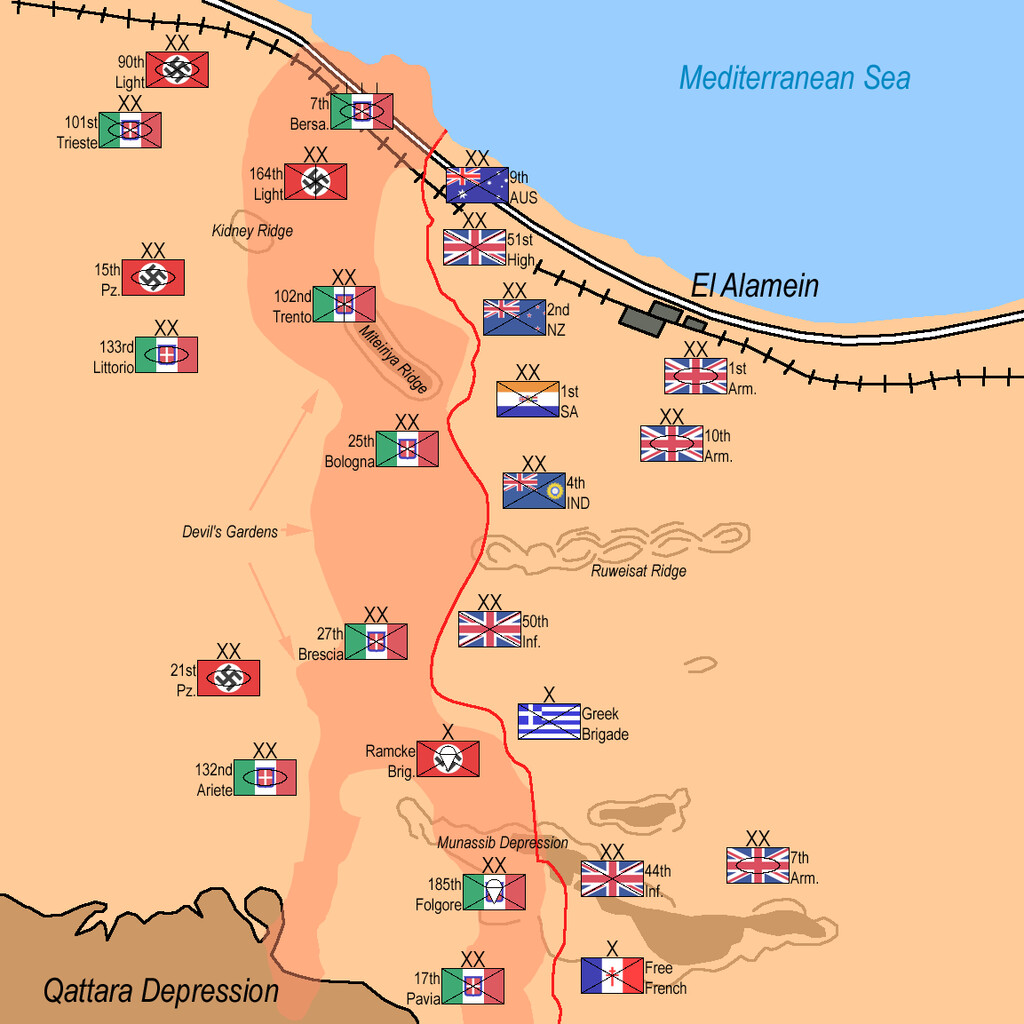

Monty continues to brief his officers on the big push at Alamein. Under his plan, the main attack is by the 30th Corps, under Lt. Gen. Oliver Leese. He commands some of the toughest outfits in the 8th Army - 51st Highland Division, 4th Indian Division, 9th Australian Division, 2nd New Zealand Division, and 1st South African Division. All are the first team. Their divisions are to take Miteiriya Ridge, codenamed “Oxalic,” and grind two corridors through the minefields. Through these corridors, the 1st and 10th British Armoured Divisions (British 10th Corps) will drive. South of that, 13th Corps, under Lt. Gen. Brian Horrocks, will attack in the south, primarily to draw off the Axis forces. Horrocks has the 7th Armoured Division - the famed “Desert Rats” - and two British Divisions, the 50th and 44th, along with two French brigades and the 1st Greek Brigade.

Monty’s plan is a reverse of all tactical thinking. In previous battles, the British have tried to defeat the Axis armor, then the infantry. Montgomery plans to destroy the Axis infantry, thus leaving the armor unsupported.

The British forces are eager to fight. The men have seen the vast caravans of supplies and artillery coming up to the front. They have heard the aggressive words of Montgomery inspiring them. And they are eager to avenge hateful defeats and humiliations. The South Africans want to avenge their countrymen’s surrender at Tobruk. 51st Highland Division has been reconstituted after its predecessor’s surrender at St. Valery in France in 1940. 9th Australian and 2nd New Zealand carry their nation’s honor on their sleeves. Up until now, Rommel has seemed invincible. Now Montgomery is determined to end that permanently.

21 October 1942

At 4 a.m., in the Mediterranean, HMS Seraph arrives at its appointed spot, five miles off the African coast, near the port of Cherchel. The sub then dives for the day. Capt. Dicky Livingstone of the Special Boat Service breaks out his canoes at 9 p.m. amid brilliant moonlight. Livingstone shares his boat with Holmes, Clark with Capt. G.B. Courtney, and Lemnitzer with Lt. Jimmy Foot. However, one boat is damaged, so Clark goes in with Captain Wright. The young Britons paddle slowly to ease the strain on the flag officers.

When the boats come ashore, they are immediately greeted by the US Consul in Algiers, Robert Murphy, who says, "Welcome to North Africa." He leads Clark - the deputy commander of the Allied invasion - up a stony path to a red-roofed villa of white stone. All hands are to stay at the villa. Clark tells Seraph he is doing so, and confirms his identity by referring to obscure and discreditable incidents in the past history of the submarine’s crew.

All across Egypt, British and Commonwealth troops attend briefings in the field on their upcoming battle, finally getting the full picture. The attack is to be launched on the evening of the 23rd, during the full moon.

The Axis are entering the battle with 108,000 men, 50,000 German, the rest Italian. They have 253 German tanks: 85 Mark IIIs, 108 Mark IIIJs (with 50mm guns), eight Mark IVs, and 32 Mark IV specials and 20 Mark II light tanks. The Italians have 368 tanks, mostly M13/40s, inferior to the British armor but still armor against British infantry. The Axis have 475 Field and Medium guns. 270 of those are German (Many of the German field artillery pieces are previously captured British guns) , the rest Italian. The Axis has 749 anti-tank guns, 448 of them German, 89 of them the feared 88mm gun. 68 are captured Russian 76.2mm guns, 290 50mm guns, 300 Italian guns , 93 of them are Italian 90 mm guns similar to German 88 mm guns in tank killing capacity. The Luftwaffe has 275 aircraft on hand, 150 of them serviceable, while the Italians have 400 aircraft, 200 of them serviceable.

Against this, the Eighth Army field 195,000 men, and 1,029 tanks. Of the tanks, 170 are M3 Grants, 252 M4 Shermans, 216 Crusader 2-pdrs., 78 Crusader 6-pdrs., 119 M3 Stuarts, and 194 Valentine infantry support tanks. British have 2,311 artillery pieces that includes 908 field and medium guns, 1,403 anti-tank guns. Of those, 554 are the outdated 2-pdr., but 849 are the modern 6-pdr. 57mm gun. The RAF has 1.280 aircraft on hand, 780 of them serviceable. For the first time the RAF has deployed Spitfires to Egypt, superior to the German Me 109s and Italian Macchi 200s.

However, the Germans have a gigantic minefield defense line, and know the attack is coming - Panzer Army Afrika’s intelligence team, from listening to British radio transmissions , but do not know exect date , timing or location.

22 October 1942

112 Lancaster bombers of RAF Bomber Command 5 Group and Pathfinders are sent to bomb Genoa, to coincide with the opening of the 3rd Battle of El Alamein. The RAF hits the Italian city on a perfectly clear moonlight night and delivers “prompt and accurate” bombing, with only 180 tons of bombs. No Lancasters are lost. Heavy damage is done in the city center and eastern districts. Many old buildings, including the Ducal Palace, several museums and churches, are destroyed. Casualties are reported at 39 dead and 200 injured. The attack damages the fragile Italian morale in Genoa.

At 3 a.m., in Cherchel, Algeria, the Anglo-American team under Mark Clark stumbles into a Moorish villa, owned by a Frenchman named Teissier. Teissier is risking his life with his hospitality. Clark will later reward Teissierby making him the French liaison officer to Clark’s US 5th Army. Livingstone and his commandos go to sleep.

At 5 a.m., Maj. Gen. Charles Mast, commanding the Vichy French Algerian Division, drives up to meet with Mark Clark. Clark tells Mast that an Anglo-American force is coming to invade French North Africa - but doesn’t say when. Mast tells Clark the Amercians must move quickly to grab Tunisia, as the Germans can send troops there by air in 36 hours. He also suggests the Americans send troops to Southern France, in case the Nazis invade the Unoccupied Zone. He also agrees to assist the Americans when they land, saying that the French will obey the orders of General Henri Giraud.

Clark and Murphy agree the Allies should send Giraud a letter giving their intentions if he should be brought from France by an American submarine. The Americans agree that France should be restored to her 1939 boundaries, be considered an ally, and gain supreme command in North Africa at the appropriate time. Mast agrees and heads back his HQ before reveille. He leaves staff officers behind to brief the Americans on the location of French forces and supplies in Algeria.

These talks drag on all day, as the French give Clark and Murphy a comprehensive briefing, down to assessments on which French forces (mostly the Navy) will resist the landings. The British commandos spend the day admiring the coastline.

The Americans plan to leave in the evening, and tell the commandos to get the boats ready at 8 p.m. As they do, Murphy’s caretaker, a “nervous little Frenchman in horn-rimmed spectacles” dashes up to say the police are arriving. Clark, his party, and the commandos head into the basement. Livingstone plans to bribe his way out - he has 5 and 10-dollar gold coins sewn into his pants, along with 1,000 franc notes - “enough to bribe every policeman in North Africa.”

The flics find the American Consul in Algiers, his vice-consul, and some French friends having a few drinks, and singing loud songs. While they pad around, Clark sits in the basement, amid dusty champagne bottles, fiddling with his carbine, muttering “How does this thing work?” One of the commandos forgets rank and barks, “For heaven’s sake, put it down!”

After two hours, the gendarmes decide to head back to town for more gendarmes. Murphy tells his guests to get moving.

The commandos and generals head down to the beach and try to paddle back to HMS Seraph. But the surf is too fierce, and flips the boats in the undertow. At one point, Clark and paddle are hurled out of a canoe, and someone yells, “Never mind the general, for heaven’s sake, get the paddles!”

Clark and his team cannot return to HMS Seraph. They look for another point from which to row out.

If an aerial observer was to look down at the deployments of the British 8th Army at El Alamein, he would see a vast concentration of food, ammunition, and petrol in the southern part of the line, with tracks leading from the rail lines to the staging areas. In the north, he would see a few empty tracks. An attack may be possible in a few days.

In reality, the ammunition dumps and pipelines are nothing but stick, string, tin, and canvas, and the vast power of the 8th Army is hiding under sunshields. And all leave is cancelled.

At 2nd New Zealand Division, the artillerymen take the day off, after putting the finishing touches on an extremely complicated fire plan. However, artillery commander Col. Steve Weir and Lt. Gen. Bernard Freyberg, 2nd NZ Division’s CO, tour the positions. So do Howard Kippenberger and 13th Corps commander General Brian Horrocks.

23 October 1942

RAF Bomber Command strikes again on Genoa, with 122 aircraft - 53 Halifaxes, 51 Stirlings, 18 Wellingtons from 3 and 4 Groups. Three RAF bombers are lost. Genoa is cloud-covered, and the RAF loses its way in the muck, dumping its bombs on the town of Savona, 30 miles from Genoa.

At 4 a.m., the surf at Cherchel, Algeria, is not much better. But Livingstone is determined to return to Seraph. He and his team dump all their gear - coats, mess tins, rations, clothes, kit, gold-laden trousers, $20,000 in gold, and three bottles of champagne. All hands struggle through in the dark, battling the surf. Two of the boats fill with water and have to be dragged onto the beach and emptied of water. But finally they spot HMS Seraph’s conning tower, and pull alongside. All wearily fling themselves onto the sub’s deck, and abandon the boats.

While Clark’s team stumble below, the gendarmes return to the villa and interrogate Murphy. He insists that he and his host have been having a loud, raucous party, and the cops believe the story.

HMS Seraph pulls out, with Lemnitzer worrying about the lost money - it’s later found - and Clark grateful to Jewell. "Doesn’t the Royal Navy have rum aboard?" Clark asks the submarine’s skipper.

“Yes, sir, but only for emergencies.”

“Well, I think this is one. How about a double rum ration for all hands?”

“Yes, sir, but someone of rank will have to sign the order.”

“Will I do?” Clark asks.

He will. He signs the order, and the crew splices the main-brace.

German agents in Spain, their binoculars trained on Gibraltar, report massive Allied naval and air concentrations there.

At Hampton Roads, Virginia, elements of the US 3rd Infantry Division embark for North Africa. It is the only invasion of the war to be loaded in the United States.

Geoffrey Barkas finds he has nothing to do at his dummy supply depots, so he drives into Alexandria to wage the paper war. The weather is beautiful. Towards sunset, he decides to camp for the night beside the trail, on a “golden evening, serene and still.”

Barkas and his crew, exhausted from their creation of phony forces, lie down amid the reddish sand, watching the sun set. Barkas thinks about his days in the trenches.

While the British camofleurs relax, the British 8th Army makes its final preparations. Brig. Howard Kippenberger walks through his men, seeing them make their final preparations. As the sun sets, 5th New Zealand Brigade’s first-line vehicles and anti-tank guns are deployed. Brig. John Currie’s 9th Armoured Brigade rumbles up to support the New Zealanders, and everyone stands around, constantly looking at their watches.

Montgomery puts out an order to his officers, with his “General Conduct of the Battle” orders: “Methodical progress; destroy enemy part by part, slowly and surely. Shoot tanks and shoot Germans. He cannot last a long battle; we can.” His personal message to the 8th Army is tougher: "The battle which is now to begin will be one of the decisive battles of history. It will be the turning point of the war. The eyes of the whole world will be on us, watching anxiously which way the battle will swing. We can give them their answer at once, ‘it will swing our way.’

"We have first-class equipment; good tanks; good anti-tank guns; plenty of artillery and plenty of ammunition; and we are backed up by the finest air striking force in the world.

“All that is necessary is that each one of us, every officer and man, should enter this battle with the determination to see it through - to fight and to kill - and finally, to win. If we all do this there can be only one result - together we will hit the enemy for ‘six,’ right out of North Africa. Let us all pray that ‘the Lord mighty in battle’ will give us victory.”

He briefs the press in the morning, and heads over to his Tac HQ in the evening, reads a book, and goes to sleep.

At 9 p.m., the British troops move to their start-lines, which are marked by the usual white tape. Kippenberger joins the 23rd Battalion, which advances single file, 50 yards apart, saying, “Good luck, boys.” The men respond, “We’ll do it, sir. We won’t let you down, sir.” Battalion CO Col. Reg Romans blows his whistle, and the lead battalion moves off to its startline. Kippenberger walks back to his command vehicle.

All across the frontline, German and Italian troops climb out of their trenches as night falls, stretch, eat their Alte Mann, and relax.

At 9:38 p.m., New Zealand artillery gunners give the order, “Lay on Serial One, HE Charge Three. Angle of Sight zero. Two minutes to go.”

In a bunker of the 164th German Light Infantry Division, Colonel Markert is sipping tea at 9:40 p.m. He says to his staff, “Tomorrow is full moon,” and thinks, “Monty does not appear to be ready; this would be the most favorable time for an offensive.”

At that moment, (9:40 p.m.), 882 British field and medium guns open fire with a roar that shakes the desert floor that is heard and felt miles away. They are joined by 125 Wellington bombers, all pounding the Axis artillery.

The eastern sky turns pink from the barrage, and the sky is criscrossed with the whistle, scream, and roar of thousands of shells. British machine-gunners fire tracer to help their spotters locate enemy positions in the dark. Bofors AA guns and searchlights do the same. Maj. Gen. Francis de Guingand, Monty’s chief of staff, watches German gun positions explode from 30 Corps HQ.

At his command vehicle, Kippenberger watches the bombardment, awed and fascinated, joined by Freyberg. “If ever there was a just cause,” Freyberg says, before departing.

“Hell was let loose,” says a 23rd New Zealad Battalion infantryman. “The sky behind us was a blaze of fire. Every man of every unit on the Alamein line will never forget till his dying day the great bombardment on the night of the 23rd. It was beyond description, the air was filled with screaming shells and the ground fairly shook under us.”

The inferno of shellfire tears apart German and Italian artillery positions and communications lines. For 20 minutes, the British guns roar. They cease fire at 9:55, the Axis artillery silenced.

For five minutes, silence hangs over the battlefield. De Guingand hops into a jeep to report to 8th Army’s Tac HQ and catch an hour or two’s sleep.

At 10 p.m., the guns speak again. This time they blast Rommel’s minefield, exploding them in bunches, creating huge gaps in the carefully-laid Axis defenses. The drumfire goes on for 10 minutes. At 10:20 the British infantry goes in - 23rd Battalion attacks at 10:23 - with bayonets fixed at high port.

The British advance on two thrusts, 13th Corps in the south and 30th Corps in the north. 30th Corps’ objective is a line called “Oxalic.” They must create two corridors for the armor to advance.

As usual, the Australians lead the attack, the 9th Australian Division under command of General Leslie “Ming the Merciless” Morsehead moving along the coastal sector north of the railway line with a diversionary raid at 9 p.m. 20th and 26th Australian Brigades make the main attack, supported by British Valentine tanks of 40th Royal Tank Regiment. The Valentines run into mines, and struggle to keep up with the Australians.

South of 9th Australian Division , 51st Highland Division attacks in its first battle, under Gen. Douglas Wimberley. The Highlanders don’t wear kilts, but every man wears a St. Andrew’s Cross of white scrim on the back for identification, and pipers accompany each platoon officer. The skirl of bagpipes, playing familiar tunes, exhilarates the Scots and frightens the enemy, piercing the din of shellfire. 51st’s objective points are given Scottish names that are home to the attackers. The Gordons and Black Watch attack Arbroath, Montrose, and Forfar, for example, while the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders will storm Paisley and Renfrew, Greenock and Striling.

“Platoon by platoon they filed past” Wimberley writes later," heavily laden with pick and shovel, sandbag and grenades - the officer at the head, his piper by his side. There was nothing more I could do now to prepare them for the battle, it was only possible to pray for their success, and that the Highland Division would live up to its name and the names of those very famous regiments of which it was composed."

Backed by 50th Royal Tank Regiment’s Valentines, the Scots advance. An officer wires, “Through the din we made out other sounds - the whine of shells overhead, the clatter of machine-guns…and eventually the pipes. Then we saw a sight that will live for ever in our memories - line upon line of steel-helmeted figures with rifles at the high port, bayonets catching the moonlight, and over all the wailing of the pipes…As they passed they gave us the thumbs-up sign, and we watched them plod on towards the enemy lines, which by this time were shrouded in smoke. Our final sight of them was just as they entered the smoke, with the enemy’s defensive fire falling among them.”

The Highlanders achieve thunderclap surprise, scooping up baffled Italians of the Trento Infantry Division, even an officer in pajamas. But the Italians recover, and take aim at the bagpipes - Piper Duncan McIntyre is hit three times. When his body is brought in, his fingers are still on the chanter. He is 19 years old.

South of the Highlanders, 5th New Zealand Brigade advances through dust and smoke, battling machine-gun fire and communications breakdowns. 23rd NZ Battalion clears its gap, and the tanks move forward. Sgt. Ray Minson takes over his platoon when his platoon leader is killed, and knocks out all enemy resistance in the Italian network of trenches and dugouts. 23rd Battalion’s objective is a crashed aircraft near a ridge. When the battalion finds a crashed plane, they assume it’s the objective. “Surely there are any number of crashed aircraft in the desert,” says an officer. Col. Romans stops the discussion by pointing at Miteiriya ridge ahead of them. “You see that rise ahead of you. That is your objective. Take it! We haven’t done any real fighting yet - let’s get cracking!”

Below the Kiwis, the South Africans from 1st SA Division advance. The Natal Mounted Rifles and Cape Town Highlanders run smack into machine gun fire and are pinned down. The Frontier Force Battalion has even worse luck, hitting an uncharted minefield that turns out to be actually a strongpoint of the German 164th Light Division. A and B companies of the Frontier Force are slaughtered by boobytraps, mines, mortars, and machine gun fire. Only 50 men are left effective. The Natal Mounted Rifles joins the attack, bringing in mortars and machine guns, overcoming the defenders. The Natal Mounted Rifles lose 189 men and capture 36 Germans.

The South African left flank consists of the 1st Rand Light Infantry, the Royal Durban Light Infantry, and the Imperial Light Horse. They also run into the 164th German Light Division, and use Bangalore torpedoes to rip apart the German barbed wire.

At the southern end of the British line, 13th Corps under Brian Horrocks, led by the 7th Armoured Division - the famed “Desert Rats” - faces the equally tough Italian Folgore Parachute Division and the German Ramcke Parachute Brigade, both hoping for action after wasting all summer, waiting uselessly to assault Malta. 7th Armoured is joined by another determined force, the 1st Free French Brigade, veterans of Bir Hakim, and 44th Home Counties Division, a new outfit.

7th Armoured’s lead force, 22nd Armoured Brigade, joined by 1st/7th Queens of 44th British Infantry Division 131st Brigade, is in position when the barrage begins. “It was a shattering fantastic sound,” writes a British officer, “drowning the subdued whispering of boots in the sand and the occasional clink of a rifle or bayonet as the infantry moved up. The din of nearly 1,000 field guns firing along the front was like gigantic drum-beats merging into one great blast of noise. As we went forward we could hear the sighing whistle of the shells overhead and the flicker of their bursts on the dark horizon and beyond…Bofors guns on fixed lines were lobbing tracers shells in a lazy curve towards the enemy lines ahead of us, to help the Queen’s Brigade maintain the correct axis of advance.”

However, the Germans are ready, and the British guns fire short. Three officers of 1st/7th Queens are killed instantly, and the Axis paratroopers kill many attackers. The tanks run into soft sand and mines. The battle rages on as clocks turn over at midnight.

24 October 1942

The RAF sends 88 Lancasters on a daylight raid on Milan, flying independently across France under cloud cover to a rendezvous at Lake Annecy. The formation crosses the Alps and hits Milan by broad daylight. Italian AA guns and air defense are both week.

Milan is completely surprised by the raid. The bombs explode before the air raid sirens go off, and the city takes 135 tons of bombs in 18 minutes. One Lanc reportedly swoops down to rooftop level and strafes the streets, which would be amazing, if true. The bombs start 30 large fires and destroy or damage 441 houses.

The Italian government admits damage to the university, the prison, the offices of the local Fascist Party, two churches, two schools, and a maternity hospital. RAF reconnaissance photographs, however, note that a number of commercial and industrial buildings are also hit, including the Caproni aircraft factory, where workers are becoming increasingly restive under war, low rations, Fascist rule, and pay caps. At least 171 people are killed. The RAF loses three Lancs.

That evening the RAF sends 71 more aircraft to Milan, losing six. This force runs into storms and flies over Switzerland, where Swiss AA gunners defend their neutrality. Only 39 aircraft hit Milan, causing little further damage.