Always an apostle of the underdog –

Ernie Pyle ignores success, feels he must keep going

Life Magazine reviews his career – He’s not the type his readers imagine

Sunday, April 1, 1945

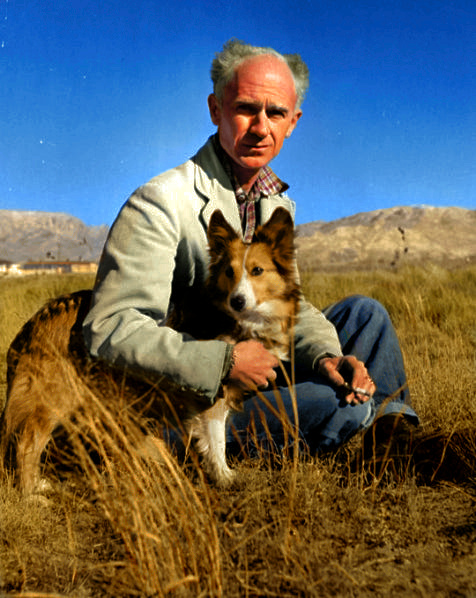

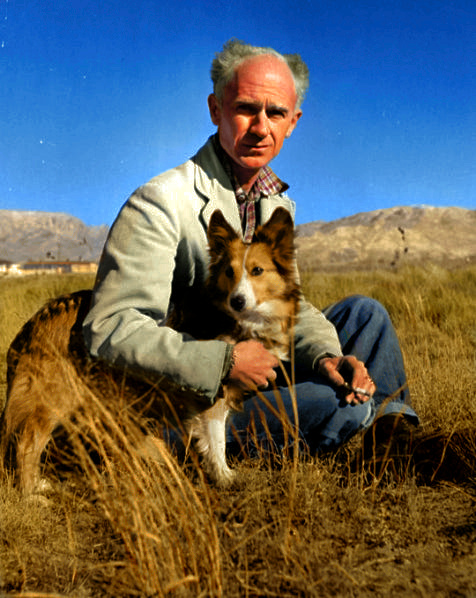

Ernie Pyle and friend ‘Cheetah’ enjoying the sun whole Ernie was home from the wars. (Photo by Bob Landry)

Success thrust itself upon him… he cares nothing for the money it has brought, and is embarrassed by the fame… but he keeps going because he feels that he must.

That’s Ernie Pyle, columnist of The Pittsburgh Press and 676 other newspapers, as he is described by Lincoln Barnett in this week’s issue of Life Magazine.

Life devotes parts of nine pages to Ernie, reviewing his career, appraising his success, and adding considerably to the general fund of knowledge about this self-effacing, individual who has become the outstanding war correspondent of World War II.

Not saintly or sad

“By his articulate admirers,” says Mr. Barnett, “Ernie has come to be envisaged as a frail old poet. a kind of St. Francis of Assisi wandering sadly among the foxholes, playing beautiful tunes on his typewriter.

“Actually,” “Mr. Barnett continues, “he is neither elderly, little, saintly nor sad.”

He is 44, stands 5 feet 8 inches tall; weighs 112 pounds, and although he appears fragile, he is a tough, wiry man who gets along nicely without much food or sleep.

His sense of humor… assumes a robust earthy color in conversation. His laugh is full-bellied. His profanity is strictly G.I.

Likes to just sit

Although Pyle is America’s No. 1 professional wander, he is fundamentally a sedentary person who likes nothing better than to sit in an overheated room with a few good friends. Sometimes he appears to find conversation less pleasurable than the simple circumstance of being seated.

His apparent agoraphobia is a byproduct neither of war nerves nor a swelled head. He has always been self-effacing, and he finds himself uncomfortable in his current eminence as the nation’s favorite war reporter, Pulitzer Prize winner and author of two bestsellers.

He has been called shy, but he is not timid. His reticence is marked by quiet dignity.

He likes people as individuals and writes only nice things about those he mentions by name in his column. “But there are a lot of heels in the world,” he says. “I can’t like them.”

Apostle of underdog

The Life article points out that Ernie has always been an apostle of the underdog. Seven years ago, after visiting a leper colony, he wrote that “I experienced an acute feeling of spiritual need to be no better off than the leper.”

“And so in war,” says Mr. Barnette, “Pyle has felt a spiritual need to be no better off than the coldest, wettest, unhappiest of all soldiers.”

The article relates that when Ernie gave his consent to the making of the movie, The Story of G.I. Joe, he stipulated that (1) the hero of the picture must be the Infantry and not Pyle; (2) that no attempt be made to glorify him, and (3) that other correspondents be included in the story.

The movie, in which Capt. Burgess Meredith plays Ernie, will be seen by troops overseas in June and be released to the civilian public in July.

Huge earnings

In spite of his refusal to capitalize on his fame when he returned from the European fronts, Ernie has made close to half a million dollars in the past two years, Mr. Barnett estimates.

While he was home, he wore one suit, which he bought for $41.16 when he landed in New York. His home is a modest house in Albuquerque, which cost about $5,000. He puts his money into war bonds and, according to Mr. Barnett, “quietly bestows substantial sums upon friends, relatives, G.I.’s and anybody else he likes.”

“Although Pyle disdains his affluence,” the article continues, “he is keenly appreciative of the aureole of national esteem and affection that now envelopes him.”

Hundreds pray for him

The emotions Pyle evokes in his public go beyond detached admiration. He is probably the only newspaper columnist for whom any notable proportion of readers have fervently prayed. The volume of prayer put forth for him each night can only be estimated by the hundreds of letters he receives from mothers and wives who declare they include him in their bedtime supplications.

For some time after D-Day, 90 percent of all reader queries that came into Scripps-Howard offices were: “Did Ernie get in safe?”

His success has been achieved without much push on Ernie’s part, the article maintains.

It declares that he took journalism at the University of Indiana because someone told him it would be an easy course.

He quit college a few months before he would have graduated, and went to work on a small newspaper in Indiana. Four months later, he went to the Scripps-Howard Washington Daily News as a copyreader.

Married ‘that girl’

“He was an excellent headline writer,” says Mr. Barnett, “but so mousey-mild his associates never dreamed he would ever be more than a pencil slave on the rim of the desk.”

Two years after going to Washington, he married Geraldine Siebolds, an attractive girl from Minnesota who had a job with the Civil Service Commission, Later, when he became a roving reporter, she was known to mullions as “that girl.”

He became managing editor of The News in 1932, but declared that he “hated the damn job.” Three years later, convalescing from influenza, he and Jerry took a motor trip to the Southwest. When they returned, Ernie turned in some articles about his trip and asked for an assignment as roving reporter.

Gets his wish

“They had a sort of Mark Twain quality and they knocked my eyes right out,” the Scripps-Howard editor-in-chief declared afterward. Pyle got his wish. His salary was raised from $95 to $100 a week and on August 8, 1935, his first travel column appeared in Scripps-Howard newspapers.

For the next five years Pyle roamed the Western Hemisphere. Those itinerant pre-war years were the happiest of his life. “The job would be wonderful,” he once said, “if it weren’t for having to write the damned column.”

Meanwhile he was evolving his special reportorial capacities and style. When war came, he had no need to revise his technique, His farmers, lumberjacks and bartenders had become privates, sergeants and lieutenants. And Phoenix, Des Moines and Main Street were Palermo, Naples and Rue Michelet.

He goes to war

“A small voice came in the night and said Go,” Ernie wrote in the fall of 1940. It was the same voice that had spoken to him in the leper colony in Hawaii. So he went off to war.

Pyle’s first overseas trip in the winter of 1940-41 multiplied readers of his column by 50 percent. Stirred by the spiritual holocaust of London and his own relentless instinct for self-immolation, he produced columns of great beauty and power. But it was not until he reached North Africa the following year that the Pyle legend began to evolve.

The article tells how Ernie, afflicted by one of his periodic colds, remained in Oran while the other reporters went to the front. There he met some obscure civilians who told him about the turbulent political situation in North Africa, and he scored an important scoop.

The doughboys’ saint

Gradually, as he moved about among the soldiers, covering the “backwash” of the war, he became the patron saint of the fighting foot soldier, the article relates. But he didn’t know it for a long time.

He thought, when he wrote it, that his famous column on the death of Capt. Waskow was no good.

He went on to Normandy, and went on suffering the privations and dangers of the soldiers. Gradually the suffering he saw began to get under his skin. He had premonitions of death. Finally, he had to come home. Soldiers wrote saying they didn’t blame him.

After a long rest he pushed off again, this time to the Pacific. He chose a small carrier because he knew he would feel more at home there – and because such ships hadn’t been receiving much notice.

“I dread going back and I’d give anything if I didn’t have to go,” he said. “But I feel I have no choice. I’ve been with it so long I feel a responsibility…”