Pyle’s closest pal writes of ‘my friend’

Hears news via radio with Army on Luzon

By Lee Miller, Scripps-Howard staff writer

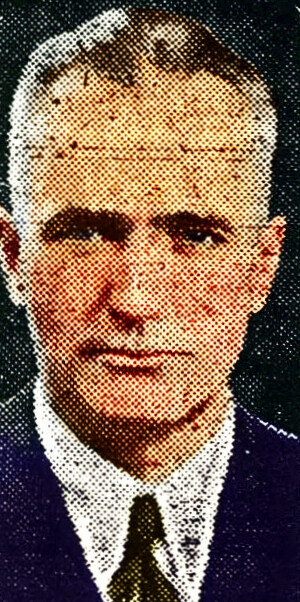

This story about Ernie Pyle was written by Lee Miller, heretofore managing editor of the Scripps-Howard Newspaper Alliance, and Ernie’s closest friend. When Ernie became famous and was roving over the world, Lee handled so much of Ernie’s business that he was jokingly referred to as “vice president in charge of Pyle.”

MANILA, Philippines (April 19, delayed) – I am tired and grieved and I don’t feel like writing anything.

They asked me to send in an article about my friend Ernie Pyle but Ernie wrote his own story. He wrote it in his blood – there with the foot soldiers whose dangers it was his self-imposed lot to share.

I was shaving out of a helmet this morning in a tent at the 49th Fighter Group, many miles from Manila. A radio came on in an adjacent tent. I couldn’t hear distinctly, but suddenly I thought I heard Ernie’s name. Jerry Thorp, with whom I shared a tent along with Paul Cranston, jumped from his chair and shouted: “What did he say?”

We stood there transfixed as the announcer went on. President Truman, he was saying, had paid tribute for the nation to the great reporter.

Details unimportant

The announcer went on with the meager details. But details seemed of no moment now. Ernie was gone – my closest friend for more than 20 years, years in which we shared some tragedies as well as pleasant things.

He was dead, dead the way he had increasingly feared he might die – in the violence of combat.

Ernie hated the thought of dying. He told me that in his first months of war he felt more excitement than fear, but that in the years that followed, as one friend after another was killed, and as he himself survived many brushes with death, he came to dread what might happen to him.

Didn’t want to go back

He didn’t want to go back to the war. He said so on return from Europe last year. He said it in New York, in Washington, in Albuquerque, in Hollywood, in San Francisco and Honolulu, where I saw him off in January. He forced himself to go, as a duty.

And it was indeed a duty. For never, surely, in the history of journalism had so many people come to trust implicitly the word of one particular reporter, nor so many people to feel personal devotion to a reporter.

I had been planning to go up to Baguio this morning. But I thought my office – Ernie’s office – in Washington would be trying to reach me, and I decided I’d better get to Manila. There was a five-hour wait at the airstrip before I got a ride in a B-24 going halfway. Meantime I talked to the air force noncoms leaving for home on rotation after more than three years in this theater.

“First President Roosevelt and now Ernie,” said Sgt. Harry A. McMahon of Memphis. “It won’t be the same back home now.”

Later when I changed from bomber to jeep, Capt. Al Stoughton of Washington said a Red Cross girl down at the airdrome had burst into tears at the news. All the way down the line, and here in Manila tonight, people have been saying: “Is it true about Ernie Pyle?”

At a ceremony for presentation of decorations to some engineer troops, a detailed account of Ernie’s death was read aloud to the hushed gathering.

Legend to men

I picked up my mail. My mother had written from Indiana, “I hope Ernie gets back all right. We’ve watched his progress on Okinawa closely and were so glad he had a safe landing.”

A delayed wireless from Washington said Ernie was planning to remain in the Ryukyus several weeks. A letter from my office enclosed clippings of several of Ernie’s columns, and a picture.

Ernie had never visited the Southwest Pacific Theater. He had planned to. Weeks ago, he wrote me that he hoped to see me on Luzon. But he was a legend to these men out here who never knew him.

It is still impossible to compass the fact that Ernie, that human, earthy, gentle, wise man, is gone from this troubled world whose collective madness he abhorred but whose shortcomings were overshadowed for him by the nobility of the individual human being.