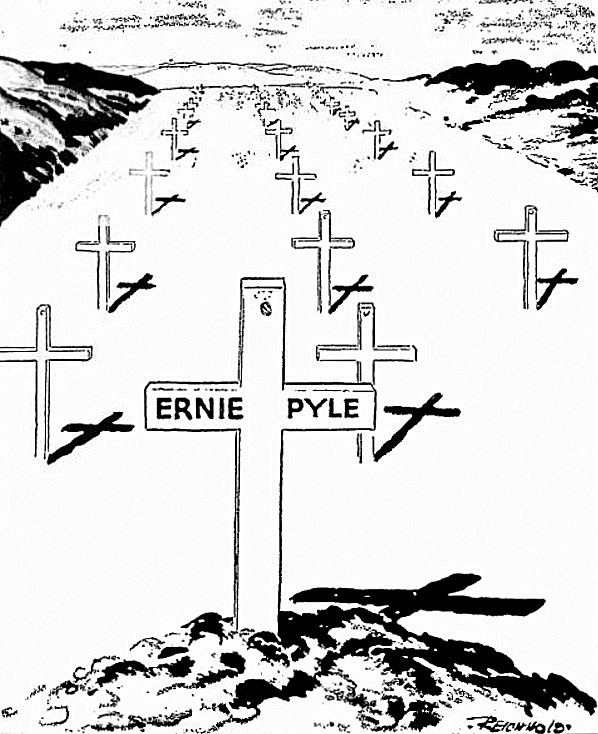

By Ernie Pyle

NOTE: This column by Ernie Pyle was part of his general running story of the battle of Okinawa, written during the campaign that led to his death. It is believed that other instalments were filed by him and will be received for publication.

OKINAWA (by Navy radio) – The company commander, Capt. Julian Dusenbury, said I could have my choice of two places to spend the first night with his company.

One was with him in his command post. The command post was a big, round Japanese gun emplacement, made of sandbags. The Japs had never occupied it, but they had stuck a log out of it, pointing toward the sea and making it look like a gun to aerial reconnaissance.

Capt. Dusenbury and a couple of his officers had spread ponchos on the ground inside the emplacement and had hung their telephone on a nearby tree and were ready for business. There was no roof on the emplacement. It was tight on top of a hill and cold and very windy.

My other choice was with a couple of enlisted men who had room for me in a little gypsy-like hideout they’d made.

It was a tiny, level place about halfway down the hillside, away from the sea. They’d made a roof for it by tying ponchos to trees and had dug up some Japanese straw mats out of a farmhouse to lay on the ground.

I chose the second of these two places, partly because it was warmer, and also because I wanted to be with the men anyhow.

Mustache trouble

My two “roommates” were Cpl. Martin Clayton Jr. of Dallas, Texas, and Pvt. William Gross of Lansing, Michigan.

Cpl. Clayton is nicknamed “Bird Dog” and nobody ever calls him anything else. He is tall, thin and dark, almost Latin-looking. He sports a puny little mustache he’s been trying to grow for weeks and he makes fun of it.

Pvt. Gross is simply called Gross. He is very quiet, but thoughtful of little things and they both sort of looked after me for several days. These two have become very close friends, and after the war they intend to go to UCLA together and finish their education.

The boys said we could all three sleep side by side in the same “bed.” So, I got out my contribution to the night’s beauty rest. And it was a very much appreciated contribution too. For I had carried a blanket as well as a poncho.

These Marines had been sleeping every night on the ground with no cover, except their cold, rubberized ponchos, and they had almost frozen to death. Their packs were so heavy they hadn’t been able to bring blankets ashore with them.

Our next-door neighbors were about three feet away in a similar level spot on the hillside, and they had roofed it similarly with ponchos. These two men were Sgt. Neil Anderson of Coronado, California, and Sgt. George Valido of Tampa, Florida (Incidentally there’s another Neil Anderson in this same battalion).

So, we chummed up and the five of us cooked supper under a tree just in front of our “house.” The boys made a fire out of sticks and we put canteen cups and K rations right on the fire.

Other little groups of Marines had similar little fires going all over the hillside. As we were eating, another Marine came past and gave Bird Dog a big piece of fresh roasted pig they had just cooked, and Bird Dog gave me some. It sure was good after days of K rations.

Several of the boys found their K rations moldy, and mine was too. It was the old-fashioned kind and we finally realized they were 1942 rations and had been stored, probably in Australia, all this time.

Making conversation

Suddenly downhill a few yards. we heard somebody yell and start cussing and then there was a lot of laughter. What had happened was that one Marine had heated a K ration can and, because it was pressure packed, it exploded when he pried it open and there were hot egg yolks over him. Usually, the boys open a can a little first, and release the pressure before heating, so, the can won’t explode.

After supper we burned our K ration boxes in the fire, brushed our teeth with water from our canteens, and then just sat on the ground around the fire, talking.

Other Marines drifted along and after a while there were more than a dozen sitting around. We smoked cigarettes constantly, and talked of a hundred things.

As in all groups the first talk is of surprise at no opposition to our landing. Then the talk drifts to what do I think about things over here and how does it compare with Europe? And when do I think the war will end? Of course, I don’t know any of the answers but we’ve been making conversation out of it for months.

The boys tell jokes, they cuss a lot and constantly drag out stories of their past blitzes and sometimes they speak gravely about war and what will happen to them when they finally get home.

We talked like that for about an hour, and then it grew dark and a shouted order came along the hillside to put out the fires and it was passed on and on, and the boys drifted away to their own foxholes or hillside dugouts, and Bird Dog and Gross and I went to bed, for there’s nothing else to do after dark in blackout country.