TOGETHER WE STAND - James Holland

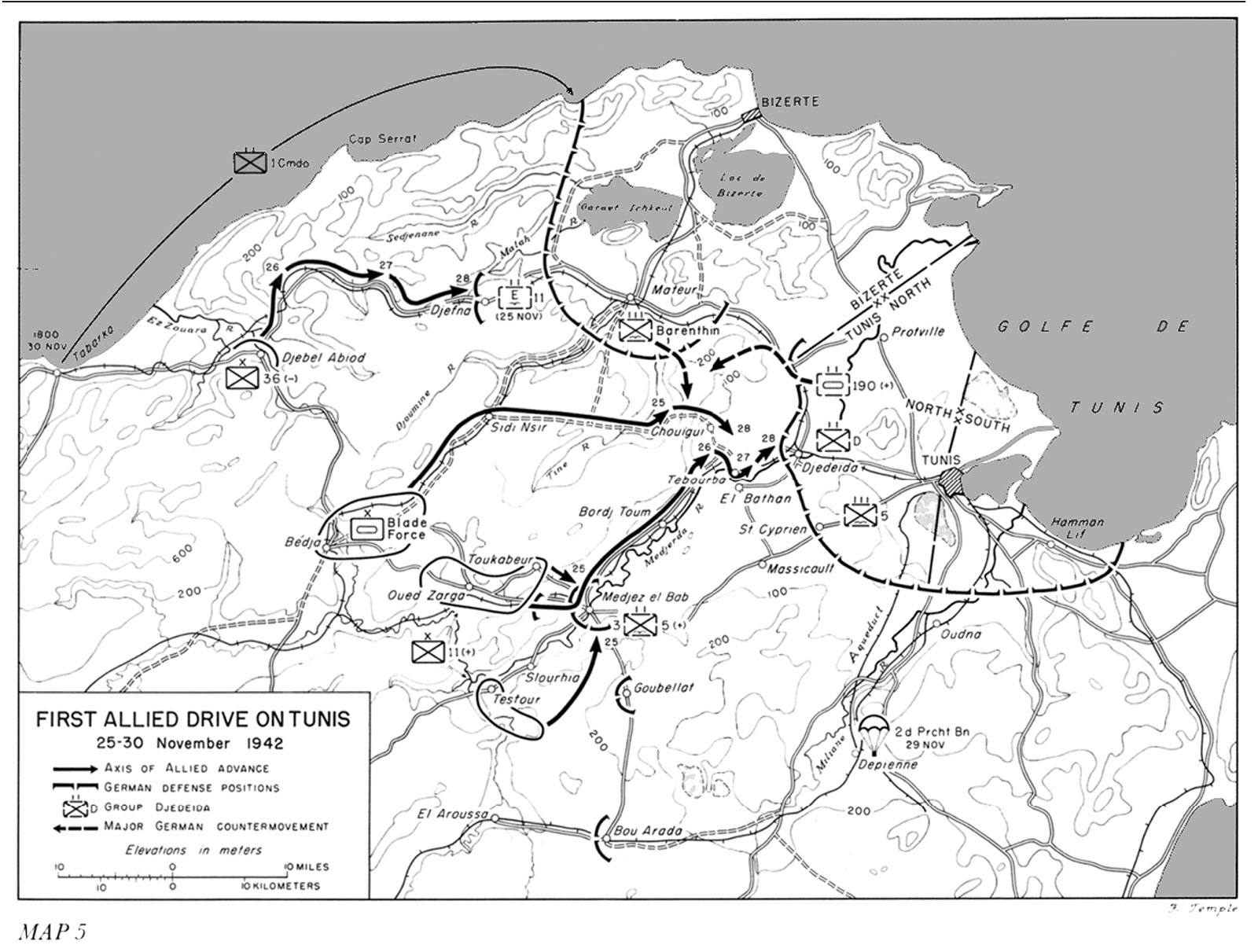

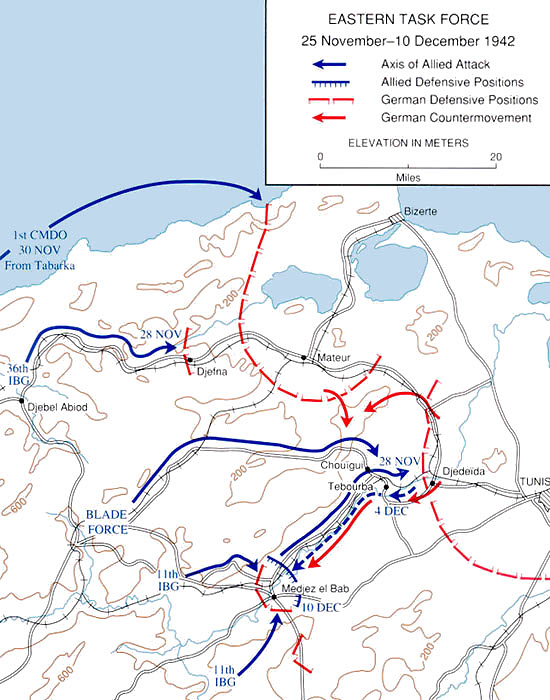

Race For Tunis

Axis reaction to the Allied landings was swift. On the day of the invasion, Field Marshal Kesselring, German C-in-C South, sent a Luftwaffe liaison officer to Tunisia to pave the way for Axis occupation of French airfields there. The following morning, he spoke in person to Hitler, who gave him a free hand to build up a bridgehead in Tunisia. Wasting not a moment, Kesselring ordered more bomber units to move to Sicily and Sardinia, from where they could attack the newly captured ports in Algeria. In addition, he sent a further two-man team to negotiate with the French authorities in Tunis, along with a parachute regiment, his own HQ Battalion, and a number of Me 109s and Stukas. These landed at El Aouina airfield just outside Tunis, and although the French commander there hastily flew off to Algiers – where he reported that over forty enemy aircraft had now landed unopposed – the French forces there simply sat back and watched. Two days later, German paratroopers took over Bizerte airfield as well.

To his mountain retreat at Berchtesgaden, Hitler hastily summoned Laval, the Vichy French Prime Minister, and Count Ciano, the Italian Foreign Minister, for talks. The Italians were especially concerned about the threat in North Africa and had, in fact, been urging Hitler to build up troops in Tunisia for several months. But until now Hitler had shown little interest in the North African campaign: he regarded it as a distraction from the main focus of his energies, the campaign against Russia. He could no longer view Africa as a colonial sideshow, however: the significance of an Allied conquest of North Africa was glaringly obvious; after all, Sicily was a stone’s throw from northern Tunisia. ‘Italy will become the centre of attack by the Allies,’ noted Ciano glumly on 8 November. Only a few days later, Churchill echoed the Italian minister by claiming that the Mediterranean was the ‘under-belly of the Axis’ from which they could attack in future. Hitler was already anxious about the sticking power of the Italians. Now fully committed in the East to a tougher campaign than he’d originally envisaged, he was aware that the collapse of his principal Axis partner would be a disaster for Germany. With this in mind, he was determined to keep Italy in the fight and to safeguard his continental empire, and so immediately ordered the Axis occupation of Vichy-controlled southern France and Corsica, and the establishment of a bridgehead in Tunisia. This was presented as a fait accompli to Laval. There were other advantages for Hitler in establishing a strong bridgehead in Tunisia. Not only would it offer an alternative supply route for Rommel, but Axis control of the central Mediterranean would force the Allies to continue supplying the Middle and Far East via the Cape. So while the war against Russia was still top of Hitler’s agenda, Tunisia – ‘that cornerstone of our conduct of the war on the southern flank of Europe’ – remained key to the German war effort and he issued orders for it to be held at all costs.

On achieving this task, Kesselring was to focus all his efforts. The Mediterranean had already been reinforced during the past couple of weeks in response to the build-up of Allied activity, but further air units were transferred from every front – even Russia – including large numbers of transport aircraft. Within two weeks of the TORCH landings, there were nearly 11,000 Axis troops in Tunisia, hastily drawn from Sicily and from reserve units in France, which included German paratrooper and Panzer grenadier units as well as the Italian 50th Special Brigade from Tripoli, partially made up of remnants of the battle-hardened Ariete Division. On 16 November, General Nehring, the former commander of the Afrika Korps until wounded at Alam Halfa, arrived to take charge; by 24 November, the 10th Panzer Division had also landed, along with a number of the new Tiger tanks. This enormous 60-ton beast, hot from the German factories, was an awesome machine. Although slow , cumbersome and often suffering too many mechanical breakdowns not to mention wasting too much fuel and required constant tracks and spare parts to replace , it mounted an 88-mm gun in its turret and had body armour that was so thick there was nothing in the US and British armament that could penetrate it.

German paratroopers in Tunisia

It was an astonishingly fast build-up and proved what German and Italian logisticians could achieve when there was proper commitment and shortened lines of communication. It also made life very difficult for the French Governor, Admiral Esteva, who was receiving conflicting orders from Algiers and Vichy, but who was also increasingly surrounded by Axis forces. Esteva opted for neutrality, although the commander of the French Tunisian Division, General Barré, quickly retreated with his troops away from the plains around Tunis and into the hills between Medjez el Bab and Beja, hoping the Allies would hurry to his rescue.However, Allied efforts to persuade the French to resist the Axis forces rushing to Tunisia had not been helped by disunity and shilly-shallying on the part of the French leaders in Algiers. Although the French had followed Darlan’s, rather than Pétain’s, orders and laid down their guns in much of French North Africa, the French admiral was continuing to blow hot and cold. Mark Clark, still valiantly leading the negotiations, felt that Darlan had ‘a disappointing reverence’ for Pétain; the French admiral seemed utterly miserable at his rejection by the Marshal.

As Admiral Andrew Cunningham , Commander of Torch Naval Forces and Royal Navy Mediterranean Fleet had pointed out, it was imperative that the Germans did not get their hands on the French fleet, but when Clark asked Darlan to summon the French Navy in Toulon and Tunis to come over and join the Allies, the admiral told him he did not have the authority. When Clark insisted, Darlan refused. ‘This,’ Clark told him angrily, ‘merely verifies the statement I made when I came here. There is no indication of any desire on your part to assist the Allied cause.’ Later in the day, Darlan changed his mind, and issued the orders as Clark had requested, while General Juin also ordered French forces in Tunisia to fight the Germans. Incredibly, Darlan then changed his mind again, and revoked the order, claiming he wanted to wait for General Noguès to arrive from French Morocco. Both he and Juin claimed it was a matter of military honour and discipline; they weren’t revoking the order, they assured Clark, merely suspending it until Noguès arrived. But the clock was ticking, and the German stranglehold on Tunisia was tightening.

By the following day, 13 November, Noguès had reached Algiers, and in the afternoon so did the Allied C-in-C. Ike, along with ABC and Harry Butcher, safely reached Maison Blanche around noon. Admiral Cunningham , Royal Navy Mediterranean Commander had been looking forward to meeting the French admiral. ‘Darlan is a snake,’ he wrote to a friend, ‘but a useful viper if we can use him.’ Like Ike and Clark, he had no compunction about dealing with Darlan if it ensured peace in French North Africa. Clark still had his doubts that the French would ever reach agreement, but word finally arrived that a solution had been reached between them. In an atmosphere that Admiral Cunningham thought was electric, Darlan announced that he would head the civil and political government of all French North Africa; Noguès would remain Governor of French Morocco; and Giraud would become the C-in-C of all French forces, which he would mobilize to help fight the Axis. Having agreed what was to become known as the ‘Darlan Deal’, Ike returned with ABC and Butch to Gibraltar, while Clark held a press conference. ‘The past four days have been difficult,’ he told reporters. ‘We have had to keep looking back over our shoulder instead of to the front in Tunisia. Now we can proceed in a business-like way.’

But while the Darlan Deal may have cleared the way politically, the Allies were discovering that nothing was happening quite as fast as they would have liked. A number of basic mistakes had been made during the initial landings, which had created crucial delays in unloading. At ‘Y’ Beach in the Oran sector, for example, an unexpected sandbar off the beach had caused a number of vehicles to sink. Elsewhere, flat batteries, missing ignition keys, and even missing drivers had also held up disembarkation of trucks and other vehicles. On British ships, ignition keys had been wired to steering wheels, but, incredibly, this had led to pilfering of toolboxes in the vehicles, the knock-on effects of which would be felt for months.

Moreover, the Allied armed forces were entirely dependent on what was brought from overseas; nothing was available locally and this included, crucially, oil and fuel. Even coal for the single railway running east had to be supplied from across the sea. From Algiers to Tunis was 560 miles of extremely mountainous country. From Casablanca, it was 1500 miles. There were only two main roads – one that weaved its way along the coast, and another around forty miles inland that twisted and turned up and down all the way. Both routes were built along highly mountainous terrain, while the existing French railway was barely functioning. In other words, it was far easier to get troops from Sicily into Tunisia than it was from Algiers. This was what Admiral Cunningham, for one, had feared from the outset, and the protracted settlement with Darlan, which had wasted precious time, had only confirmed his fears. ‘Once more,’ he wrote, ‘I bitterly regretted that bolder measures had not been taken in Operation TORCH, and that we had not landed at Bizerte, as I had suggested.’

The weather also hindered operations, as US Army Air Force Lieutenant Jim Reed discovered when he finally landed at Port Lyautey. Air cover for the landings in French Morocco had been provided by planes of the US Navy, as they were the only aircraft able to rearm and refuel on aircraft carriers. This was why the 33rd Fighter Group on board the USS Chenango did not fly off until the airfield at Port Lyautey had been secured. The first P-40s were catapulted off the deck on 10 November. Jim Reed had been sitting strapped into his plane, Renee, when suddenly the launchings stopped. He couldn’t understand it and began to think the worst until word got through that the halt was because one of the pilots had crashed on landing.

The next day, the aircraft began taking off again. Like for Duke Ellington before him, launching his P-40 Warhawk from a carrier was a new experience for Jim. The day before, he’d noted how nearly every aircraft had initially dipped beneath the end of the Chenango. Lieutenant Jones, the pilot five ahead of him, took off and never reappeared – unable to get out in time, he sank with his plane. When it was his turn, Jim gunned the throttle and with full flaps down, surged forward, hoping for the best. Clearing the deck, he dropped until he was just off the water, but with his engine still racing he slowly but surely began to inch higher into the air. Flying over the shimmering white city of Casablanca, Jim and several others headed up the coast to Port Lyautey, where they were met by scenes of carnage. Wrecked aircraft and bomb craters littered the field. Realizing he was not going to clear the craters, Jim flew round again, but as he touched down he noticed another bomb crater. Breaking hard, he swerved around it but the force caused his plane to tilt to one side, damaging the wing. Jim was feeling bad enough but the Group Commander, Colonel Momyer, gave him an earful. ‘Don’t feel too bad,’ another pilot told him soon after, ‘that SOB tore his all to pieces.’

The 33rd FG lost 17 out of 77 aircraft, thanks to the craters, thick mud, and because they’d been told to keep strict radio silence. As a result, none of the incoming pilots had been warned of what to expect at Port Lyautey. It was hardly an auspicious start.

With the airfields now in Allied hands, the mass of pilots and aircraft clogging up the narrow confines of Gibraltar could start heading over to Algeria. RAF Squadron Leader Tony Bartley had arrived at Gibraltar with his 111 Squadron on 4 November, with speculation still rife about their ultimate destination. Tony was praying it wouldn’t be Malta, which everyone knew was a brutal posting. With several days to idle away, he and a number of other pilots had spent much of their time in the officers’ mess, which was decorated with oak beams like an English country pub and even had ‘The Victory Inn’ painted above the door. He was there when news finally arrived on 8 November of the Allied landings in North Africa. ‘As a score of British and American fighter pilots sat around the Victory Inn bar,’ he wrote, ‘we raised our tankards, and drank to the best kept secret of the war.’

On the 11th, Tony led twelve Spitfires to Maison Blanche. He had been worried about having enough fuel for the journey and sure enough, within sight of Algiers, two of his pilots called up on the R/T and told him they had run out of petrol. ‘Can you make land?’ Tony asked them; they would try, they replied. As he flew over the massed ships in Algiers harbour, another of his pilots called up to say his engine had died; so only nine made it to Maison Blanche. As Tony taxied off the runway, came to a halt and clambered out of his Spitfire, he felt tired, hungry and depressed. A highly experienced fighter pilot, and veteran of Dunkirk and the Battle of Britain, he had flown operationally almost constantly since the beginning of the war, save for a brief period of test flying, and was frankly exhausted before he had even reached Gibraltar. Now in North Africa, he was filled with bleak forebodings. The airfield itself, like Port Lyautey, was littered with aircraft. Across the far side were some bombed-out hangars. Food was scarce and there was no accommodation. ‘Just scrounge what you can,’ the wing commander told him. Tony’s other pilots had gathered round and heard this news but said nothing, smoking in silence instead. By nightfall the three missing pilots turned up; thankfully, only one was hurt, arriving with a bandaged foot.