Battle for Cherbourg

Time as well as harbor is at stake, for defense lets foe prepare for next blow

By Hanson W. Baldwin

London, England – (June 25)

The battle for Cherbourg, which was reaching its climax tonight, is a battle for time as well as conquest.

The eventual issue, as far as Cherbourg is concerned, is not in doubt; U.S. patrols have pushed into the streets of the city and at least one German propaganda agency has written the city off. There has never been much doubt, since our rapid penetration of the Atlantic Wall and our severance of the approaches to the Cotentin Peninsula, that Cherbourg would fall. What has been in doubt is how long the battle would take.

Cherbourg is naturally defensible by either land or sea; stouthearted defenders with the will to die might hold it for a long time. Obviously, it is to the German interest to make a protracted and vicious defense. The longer the facilities of the port can be denied to us by combat and by demolition, the better it will be from the German point of view. For the Germans know as well as we do the difficulties of unloading over open beaches; they know that the larger our armies grow in Normandy, the harder will be the task of supplying and reinforcing them unless we have a port.

Allies hampered by weather

They know, too, that our building to date has been made more difficult by unfavorable weather; gales and low overcasts have hampered our landing craft and reduced the margin of our air superiority. A long defense of Cherbourg, therefore, would give the enemy time. He might have the opportunity to overtake us in the supply and reinforcement race and he would be able to strengthen his positions along the high ground south and east of the Cotentin Peninsula.

The fierce fighting in Cherbourg and the bitter enemy resistance on the eastern flank of the Allied beachhead reveal something of the enemy’s intended strategy. The Germans have not yet committed the bulk of the strength of the rest of their divisions to Normandy. There are some 60 enemy divisions in France and the Low Countries and at least half of these could be thrown against us. But today there are not more than elements of 14-17 divisions facing our troops in Normandy, including those units hopelessly encircled in Cherbourg.

In a considerable part, this slow German buildup is the result of our interference by air with the enemy’s communications lines. But in part the slow rate of German reinforcement is deliberate; the enemy has not “shot the works” in Normandy because he fears another Allied landing elsewhere.

British offer threat

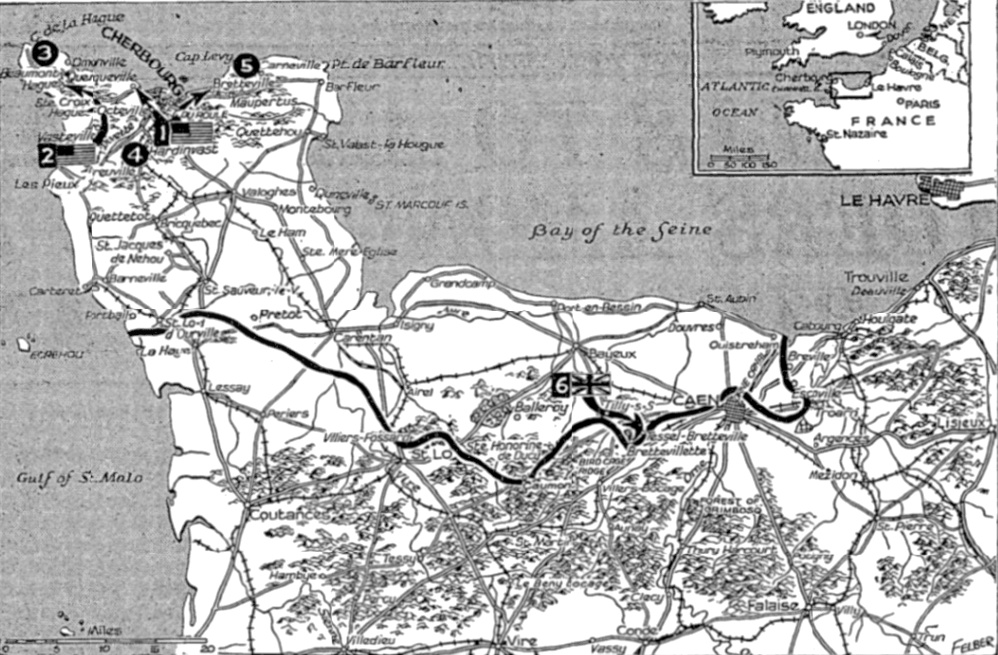

Such a strategy of cautious waiting would explain the fierce resistance offered on the British sector of our beachhead, the enemy has been constantly and consistently trying to whittle down the British bridgeheads across the Orne River and has so far strongly opposed with the majority of his tank forces the inland expansion of the British flank. It is the British flank that is outside the Cotentin Peninsula proper; it is the British flank that offers the eventual threat to Le Havre, to Rouen or to Paris.

The containing of our Normandy beachheads within the Cotentin Peninsula, therefore, seems to be the enemy’s strategy. Meanwhile, he appears to be trying to build up a mobile reserve to meet any other landing.

The enemy knows as well as we do that the Cherbourg Peninsula along will not be a sufficiently large base for an operation as huge as the conquest of France. He fears the great numbers of U.S. divisions that have never yet been in action but are trained and ready. The enemy is not likely to commit his full strength to battle either in the air or on the ground until he is certain that we shall not strike again against the coast of Western Europe.

Such a strategy explains the furious defense of Cherbourg, the holding and bitter delaying resistance south of the Cotentin Peninsula and the counterattacks against the British flank. The triumph of such a strategy would be to rob us gradually of the initiative that the Allies have not yielded since June 6 and to halt slowly the momentum and impetus of our Normandy drive. The failure of such a strategy would mean the rapid conquest of Cherbourg by the Allies and the expansion of the British flank southward and possibly eastward.

That is why the news tonight is encouraging. But time is still an important element in the victory.

Normandy wounded evacuated swiftly

Navy ‘overprepared’ because estimates exceed casualties

Aboard a U.S. cruiser, off the French coast (UP) – (June 24, delayed)

The task of moving thousands of wounded men from the Normandy beachhead to Great Britain by sea has almost been completed and was accomplished with complete success, Navy Capt. George Dowling said today.

Of the total wounded, slightly more than 5,500 were Germans or members of the polyglot forces making up the enemy armies in the invasion area.

Capt. Dowling said that his medical forces had been 50-75 percent overprepared for their task in the invasion. “We got ready for the worst – which of course didn’t happen,” he said.

Capt. Dowling used his experience in the Mediterranean, gleaned from handling the casualty evacuation in Sicily, to estimate what he needed in the invasion. In the early stages, the handling of all casualties fell entirely to naval transports and LSTs, which were rigged to take care of at least 200 wounded each after depositing their cargoes ashore.

Then practically every small craft which went to the beach, including the comparatively commodious, if flat-bottomed, types such as Tank Landing Craft (LCTs) were pressed into service to keep the lines of wounded moving.

The greatest percentage of the wounded have only minor injuries to arms and legs.