The Free Lance-Star (June 19, 1944)

NAZIS FAIL IN ATTEMPT TO BREAK FROM TRAP

9th Infantry Division cuts peninsula below Cherbourg

Over 25,000 Nazis caught in pocket

By Wes Gallagher

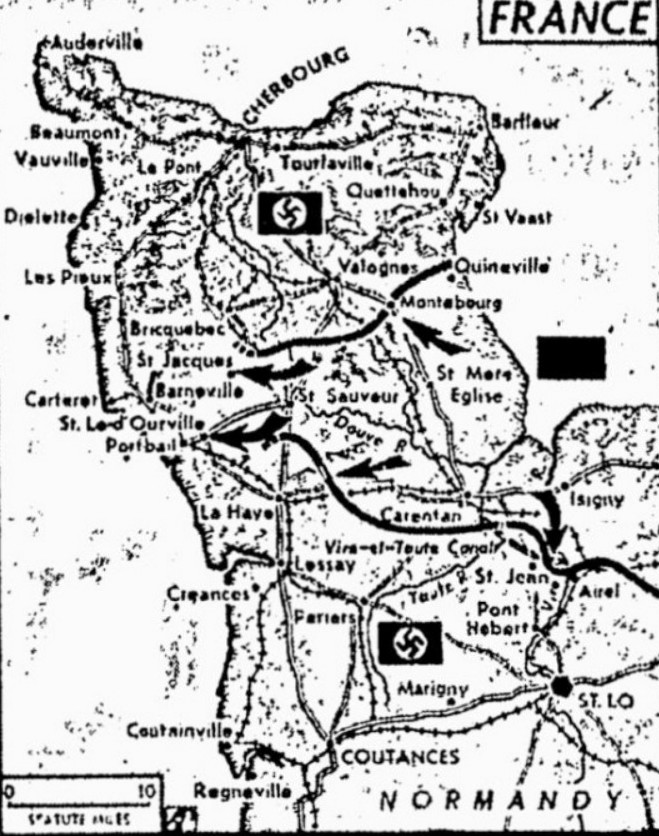

Breakthrough below Cherbourg

Arrows pointing to Saint-Jacques and Saint-Lô-d’Ourville indicate where U.S. troops have broken through German lines to cut off Cherbourg. The Americans reached the coast Sunday.

SHAEF, London, England (AP) –

Lt. Gen. Omar N. Bradley’s U.S. troops squeezed within eight miles of Cherbourg today and shelled the strategic port with their big guns tonight.Steadily strengthening their hold all across the peninsula, the Yankees turned back a single desperate German attacks to break out of the trap, struck out both north and south to widen their cordon and captured Bricquebec, only 11 miles south of the southern edge of Cherbourg.

SHAEF, London, England (AP) –

The U.S. 9th Infantry Division has crushed a German attempt to burst out of the American trap bottling up perhaps 25,000 to 40,000 Nazis below Cherbourg, hurling back a thrust 13 miles due south of the port, SHAEF announced today.

The Germans lashed out in the darkness in a heavy local attack near Saint-Jacques-de-Néhou, but were thrown back with heavy losses.

Toward the eastern flank of the 116-mile Normandy front, British forces battled into the northern end of shell-torn Tilly-sur-Seulles, with the Germans still holding in the southern part of the town between Bayeux and Caen.

Lt. Gen. Omar N. Bradley’s troops, laying siege to Cherbourg after thrusting a seven-mile-wide corridor clean across the peninsula, are now building up strength for “the next step,” Supreme Headquarters said.

German guns laid a heavier shell barrage on American-held Carentan, stronghold near the eastern base of Cherbourg Peninsula.

Other Americans on the northeastern end of the ling choking off Cherbourg fought toward the port from the Montebourg area, 14 miles to the southeast.

Local advances were scored on other sectors of the beachhead, SHAEF said.

Germans in trap

The Americans quickly broadened the corridor flung across Cherbourg Peninsula.

The trapped Germans appeared to have the choice of fighting to the death or surrendering.

The spearhead of Gen. Bradley’s spectacular drive to capture the big port of Cherbourg, developed by Napoleon, was the U.S. 9th Infantry Division. The capture of a French naval base would be an old story for this division, for the 9th Division broke through German defenses to take Bizerte, Tunisia, 13 months ago under Maj. Gen. Manton S. Eddy.

U.S. forces that severed the peninsula were busy widening their breakthrough path to the Atlantic coast, which even last night was seven miles wide. They were driving the Germans down toward La Haye-du-Puits, into what appeared to be another trap.

If this spearhead takes the town of La Haye, the Germans in that area will be in another pocket – between Saint-Lô-d’Ourville and the Atlantic coast.

A third U.S. column under Bradley’s command struck south of Lison to within six miles of Saint-Lô, important rail and highway junction in the Fire River Valley.

Fighting in streets

Almost all the advances on the Normandy beachhead reported today by Supreme Headquarters were on the American side except at Tilly-sur-Seulles, 11 miles west of Caen, where a British division broke through German defenses in a small breach and was fighting in the streets of Tilly.

All along the rest of the beachhead front, there were brisk small actions as Gen. Sir Bernard L. Montgomery, Allied ground commander, built up his forces for a typical “Monty” punch backed up by thousands of big guns.

Beach areas were quiet and unloading of men and materiel proceeded at a rapid rate.

One officer returning to Britain said that it was quieter behind the lines on the beachhead than in southern England, where the Germans sent over hundreds of rocket bombs, causing casualties and damage, particularly among the civilian population.

But in six days of incessant bombardment with the new weapon, the Germans had failed to halt the dispatch of a single ship to the beachhead.

On the beachhead side, the German Air Force had virtually disappeared, which might be an indication that Marshal Erwin Rommel was conserving his forces for an all-out attack.

Using old guns

German troops in the Cherbourg area are not of the highest quality, and they have been using many horse-drawn guns. Many of which have been knocked out by Allied strafing planes.

The Germans have a strong perimeter defense around Cherbourg and undoubtedly Hitler’s orders will be to hold on to the last. There is no chance for the German garrison to escape, since the Allies control all sea and air routes.

The German-held Channel Islands, which have many heavy guns, may give the Allied western flank a good deal of trouble, but so far, U.S. and British battleships have been able to deal with any coastal defenses encountered.

While the Germans were expected to attempt destruction of the port of Cherbourg, they are unlikely to prevent its use by the allies. The naval docks, especially, are hewn out of solid rock and there is little the Germans can do against these.

‘Desert Rats’ in line

It was disclosed today that on the eastern end of the beachhead, Montgomery has under his commander the British 7th Armored Division, famed as the “Juba,” or “Desert Rat” Division.

“Monty” was apparently biding his time, as always, to launch an all-out blow to beat a way out of the beachhead and into the open country of France.

When the time comes, it is more than likely that the “Desert Rats,” who Montgomery insisted be brought to England, will be playing a major role in the assault.