On the 27th October, 1941, Admiral of the Fleet Sir Roger Keyes was succeeded as Director of Combined Operations by Captain the Lord Louis Mountbatten, G.C.V.O., D.S.O., A.D.C., who was promoted Commodore First Class, and on the 18th March, 1942, Acting Vice-Admiral, when his title was changed to Chief of Combined Operations. At the same time he was granted honorary commissions in the Army as a Lieutenant-General and in the Royal Air Force as an Air Marshal. He at once set about planning a raid on a part of the occupied coast of Europe where, it was hoped, the enemy would least expect to be attacked. The country chosen was Norway, the place Vaagso, some hundreds of miles south of the Lofoten Islands so successfully visited in the previous March.

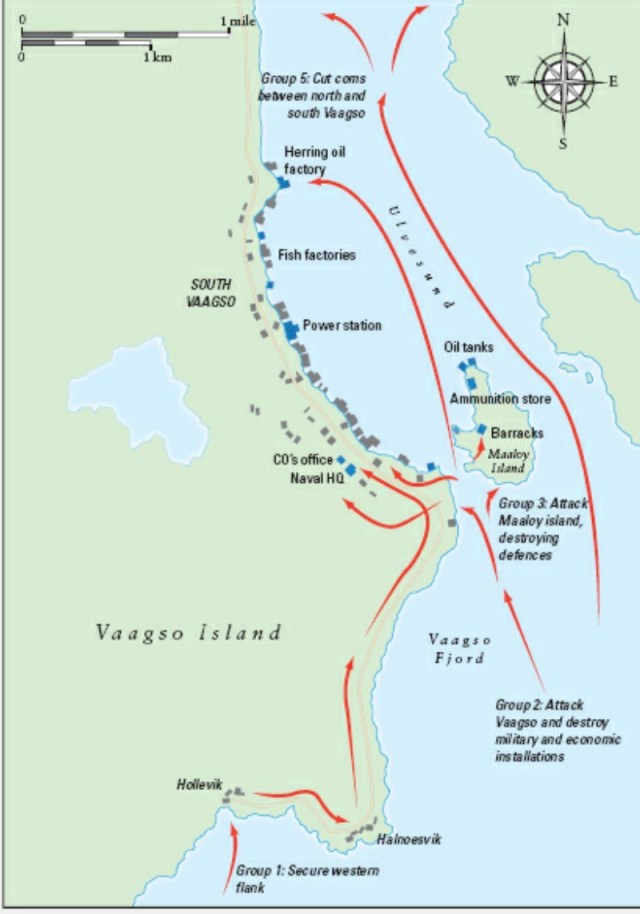

The object of the raid was, while harassing the German defences on the coast of South-West Norway, to attack and destroy a number of military and economic targets in the town of South Vaagso and on the nearby island of Maaloy, and to capture or sink any shipping found in Ulvesund. Ulvesund is the name borne by the strip of water on which the port of Vaagso lies and which divides the island of that name from the mainland. It forms part of the Indreled, that narrow passage which stretches along so much of the coast of Norway, and is in the nature of a more or less continuous channel bounded by a chain of islands on the one hand and the mainland of Norway on the other. Through the Indreled passes most of the coastwise traffic, for, by so doing, ships can use the protection afforded by the chain of islands. At certain points the Indreled is broken, and one of these is situated at the north end of Ulvesund at a point where it joins a wide bay. Ships sailing northward must cross this bay and double the peninsula of Stadtlandet, to the south of which lies the island of Vaagso. They tend, therefore, to congregate in Ulvesund, where they remain awaiting a suitable moment to pass into the open sea round the end of Stadtlandet, which is noted for its storms, and then northwards once more under the cover of the numerous islands. Running roughly at right angles to Ulvesund is Vaags Fjord; where the two stretches of water meet, there is a small island named Maaloy, opposite which is the town of South Vaagso.

The Germans had not forgotten to fortify the southern end of Ulvesund, and they had established coastal defences on the island of Maaloy itself, as well as in and near the town of South Vaagso opposite. On Maaloy, a battery of field guns had been mounted, and there were also anti-aircraft batteries and machine guns, while four miles to the southward was a battery of fairly heavy guns, possibly of French origin, situated on the island of Rugsundo; they were laid so as to fire westward down Vaags Fjord. Both Maaloy Island and South Vaagso were garrisoned by German troops, and it so happened that those in the town had been reinforced a few days before the attack by a detachment sent there to spend Christmas.

It was decided to approach the town and island up Vaagso Fjord, the entrance of which is marked by two lighthouses at Hovdenoes and Bergsholmene. On reaching the small bay behind Halnoevik Point, south of the little village of Hollevik, a short distance from South Vaagso, the landing craft from the assault ships were to be lowered and landings made first under cover of a naval bombardment and then of smoke laid by aircraft. Once ashore, the island of Maaloy and the town of South Vaagso were to be captured and anything of value to the enemy, such as fish-oil factories, destroyed.

After carrying out a number of rehearsals the force sailed on Christmas Eve, arriving at an anchorage on Christmas Day. Very heavy weather was met with. During the passage the secretary to the captain of one of the infantry landing ships invited his commanding officer to the cabin and showed him a table moving rhythmically up and down the wall, a distance of some six inches. It was eventually discovered that this levitation was due to the heavy seas, which were literally squeezing the sides of the ship. The infantry landing ships suffered some damage. This vas repaired; but since the weather did not immediately abate, it was decided to postpone the operation for 24 hours. The men were, therefore, able to eat their Christmas dinner in comfort.

The weather having improved, the force sailed at four p.m. on Boxing Day with the promise of still further improvement. Nor was the promise belied; the storm died down, and by the time the Norwegian coast was reached, weather conditions were perfect. The ships moving across the North Sea out of the sunset into the darkness of the long winter night were a fine sight.

Operation Archery Map

In the van was HMS Kenya, a six-inch cruiser, flying the flag of Rear-Admiral H. M. Burroughs, C.B., and in line astern behind him came , four Royal Navy escort destroyers then the infantry landing ships carrying 570 commandos. While it was still dark, landfall was made exactly at the estimated position and time. “We approached from the west into the promise of dawn,” says one who was on the bridge of the “Kenya.” “It was a very eerie sensation entering the fjord in absolute silence and very slowly. I wondered what was going to happen for it seemed that the ship had lost her proper element, that she was no longer a free ship at sea.

The naval bombardment opened at 8.48 a.m., the HMS Kenya firing a salvo of star shell which lit up the island of Maaloy, showing not only the target to the naval gunners, but also the place where they were to drop their smoke bombs to the crews of RAF Hampden bombers overhead. This salvo was followed by further salvos of six-inch shells. Two minutes later the destroyers joined in the bombardment which lasted nine and a quarter minutes. During that brief period between four and five hundred six-inch shells fell upon a space not more than 250 yards square.

The Germans on the island had been caught unprepared. They were following their usual routine: the gunners were being roused by a loud-voiced N.C.O., the officer commanding was shaving, his batman, whose turn it was that morning to man the telephone connecting headquarters with the look-out post, was cleaning his officer’s boots on the table beside the instrument. So busily engaged was he upon this task that he allowed the telephone bell to ring, and did not trouble to pick up the receiver. The German gunners thus received no warning. Outside the barracks on the island of Maaloy, there was a naval signalling station established on its highest point. The signaller on duty received a message flashed by lamp telling of the advent of our forces. He ran down to the small bay on the north side of the island, leapt into a boat and rowed as fast as he could to the headquarters of the German Naval Commandant on the main island of Vaagso. Here he delivered the warning, but when asked whether he had warned the army gunners on Maaloy he replied, “Oh, no, Sir; it is a military battery, and this is a naval signal.” The Germans are a methodical people. The landing craft carried troops belonging to No. 2 and No. 3 Commandos, a detachment of Royal Engineers from No. 6 Commando, and some men of the Royal Army Medical Corps from No. 4 Commando. With these British troops was a detachment of the Royal Norwegian Army. To this body of men, made up of 51 officers and 525 other ranks, five general tasks had been entrusted. For their fulfilment they were divided into five groups. Group 1 was to land near the village of Hollevik, on the southern shore of the island of Vaagso and a short distance from the town of South Vaagso. They were to clear the area and then move along the coast road and remain as a reserve to Group 2. Group 2 was to attack the town of South Vaagso itself and destroy a number of military and economic objectives, including the canning factory, the power station, the Firda fish-oil factory, and the herring-oil factory. Group 3 was to capture Maaloy Island. Group 4 remained in its landing craft as a floating reserve to be used by Brigadier (now Major-General) J. C. Haydon, D.S.O., O.B.E., Irish Guards, the Military Force Commander, when he thought fit. Group 5 was to be carried on board the destroyer HMS Oribi up Ulvesund and landed between the towns of South and North Vaagso to cut communications between them.

Saunders MC, Hilary St. George. Combined Operations;