Chapter 12: Breakthrough at Akarit

Eighteenth Army Group Plan

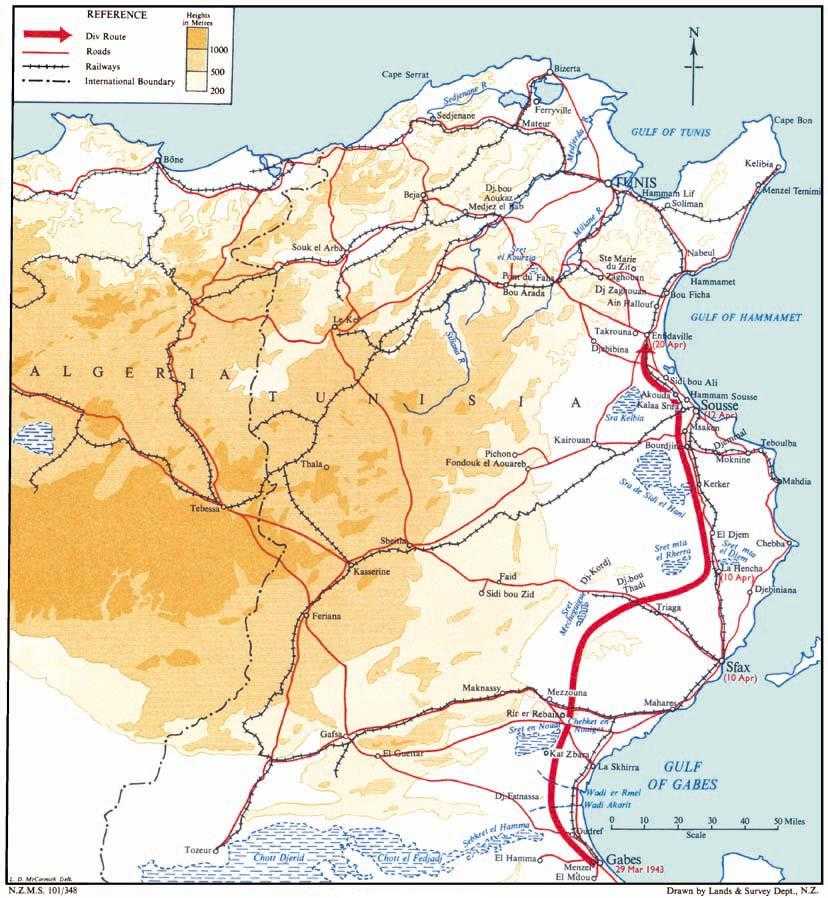

WHILE all the turmoil had been going on between Medenine and Gabes, elsewhere Eighteenth Army Group was increasing its activity after the upheaval at the end of February. There have been occasional references in preceding chapters to the action taken by 2nd US Corps in attacking towards Maknassy, and this pressure was kept up in early April but without much success. Farther north First Army was now organised into 5th and 9th Corps – which comprised 6th Armoured, 1st, 4th, 46th, and 78th British Divisions – and the French 19th Corps of about two divisions. On this front an Anglo-French force resumed the offensive north of Medjez el Bab on 28 March, and in the course of a few days advanced some 18 miles. It was intended that this offensive should continue and free Medjez from enemy threat.

Alexander by this time had prepared a long-term plan for ending the war in North Africa, of which the first two phases were to be the advance of Eighth Army through the Akarit position and a thrust by 9th Corps towards Kairouan, so threatening the rear of 1st Italian Army. (In the preliminary stage of the second phase, American troops entered Fondouk on 27 March.) By these two offensives Alexander would obtain the use of the coastal plain west and north of Sousse and, in his own words, ‘seize and secure airfields … from which we can develop the full weight of our great superiority in the air, thereby paralysing the enemy’s supply system’.

Eighth Army Plan

There was still a chance – or perhaps it would be better to say a hope – that 10th Corps might secure the Akarit line without a formal attack. Pressure by 2nd NZ Division might enable 1st British Armoured Division to pass through. This possibility was discussed by Montgomery with Horrocks and Freyberg at a conference south of Gabes on 30 March, the outcome being that Horrocks was to consider whether or not this was practicable. In the meantime 30th Corps would prepare a plan for a set-piece attack.

The New Zealand Division continued to test the defences on 30 and 31 March, after which Horrocks reported that the line was firmly held, and that 2nd NZ Division could not get through without heavy fighting, and resultant heavy losses. This was contrary to Montgomery’s wishes. First, he did not want to incur heavy casualties at a time when the end in North Africa was seen to be inevitable, and when he himself knew that Eighth Army was to be the British component of the Allied forces to invade Sicily. Secondly, he wished to use 2nd NZ Division in the exploitation beyond Akarit.

Thus the burden fell on General Oliver Leese’s 30th Corps. A first plan was produced in which 51st (Highland) Division would relieve 2nd NZ Division and keep up the pressure with a view to attacking later, but only if necessary, for the hope that set-piece action could be avoided still continued. Part of the reason for this lay in the results that would ensue from a successful offensive by 2nd US Corps, which at the best would reduce Eighth Army’s part to a follow-up; but this hope proved illusory.

General Oliver Leese , 30th Corps commander

The final decision, therefore, was to launch an attack with three divisions, to open a gap for 2nd NZ Division, for 1st British Armoured Division to follow through, and for 10th Corps to take up the pursuit with these two divisions. Codename for the operation was SCIPIO, to be launched on 6 April. Montgomery could not wait for the next moon, and this time the attack was to be in the dark, an hour or so before daylight.

There were good reasons for these changes of plan, but the outcome was a rather bewildering number of Army and Corps operation orders and instructions giving many alternatives, changes in responsibility for sectors, and transfers of formations during the battle from one corps to another. The result, however, was a brilliant success, and further evidence that Eighth Army could take such troubles in its stride.

The Terrain

The position now confronting Eighth Army was known to both sides as the ‘Akarit Line’, but was sometimes described by one or the other as Wadi Akarit, the Gabes Line, the Gabes Gap, or the Chotts. Had Rommel had his way, it would have been prepared when the Battle of El Alamein was seen to be decisive and the Allies had landed in Algeria, and there would have been only delaying action between Egypt and Akarit during the withdrawal. Rommel was reinforced in this opinion after inspecting the Mareth Line in January and confirming that it could be outflanked. The outstanding virtue of the Akarit Line from the German standpoint was that it rested on the sea to the east and the Chotts to the west and could not be outflanked. The western end rested on Sebkret el Hamma (the eastern end of Chott el Fedjadj), which was virtually impassable.

Wadi Akarit itself ends at the coast about ten miles north of Oudref, trends towards its source just south of west for about four miles, and then bends to the south-west for another four miles, at which point it disappears in the low watershed between the coastal slope and the inland descent to Sebkret el Hamma. The wadi banks in the lower reaches are steep. There is a gap of only about one mile between the western end (the source) of Wadi Akarit and the eastern end of Wadi Telman, which drains into the Sebkret. Both wadis are normally dry.

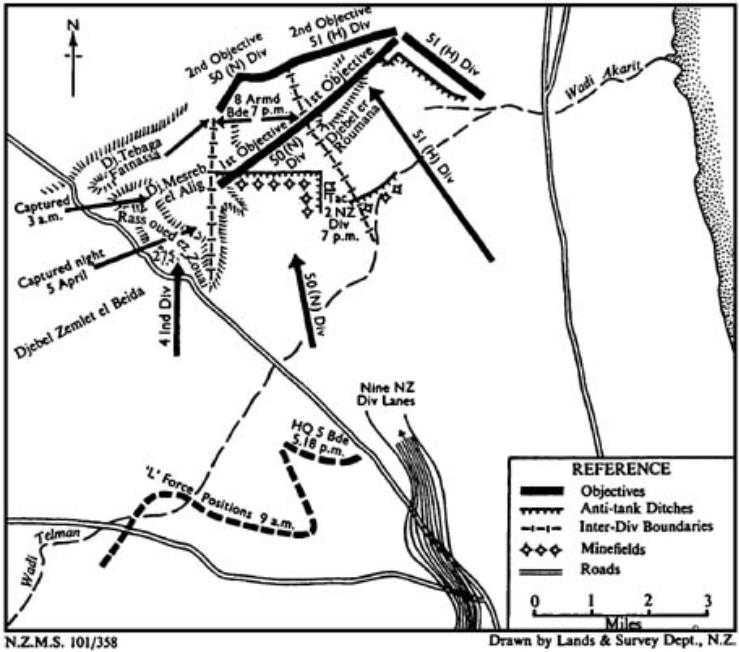

Behind Wadi Akarit and Wadi Telman is a line of hill features, the eastern end of a range north of the Chotts. Starting from the west these are (a) Djebel Zemlet el Beida; (b) Djebel Tebaga Fatnassa, a much higher feature with three separate peaks named from south to north Rass oued ez Zouai, Djebel Mesreb el Alig, and Djebel Tebaga Fatnassa itself, together with a fourth peak to the east of the last-named called Djebel el Meida; and (c), three miles farther east across a marked col, Djebel er Roumana, often known as Point 170. These features completely overlook the country south of Wadi Akarit.

In the approaches to the Wadi Akarit position the going was difficult off the roads owing to frequent small wadis, marshes, and patches of soft sand.

The enemy made use of Wadi Akarit itself for his main defence line for the first five miles from the sea. From there an anti-tank ditch carried on south of west for a mile and a half and then ran north for half a mile and west for two miles, this last stretch covering the gap between Djebel er Roumana and Djebel el Meida. It was covered by a minefield throughout. Farther west the enemy relied on the naturally broken ground of Djebel Tebaga Fatnassa and Zemlet el Beida, strengthened by some defensive works. There was a second anti-tank ditch resting on the rear (northern) end of Djebel Roumana and running thence south-east to Wadi Akarit. Both sides of all these ditches were staked, and over the whole length of the line there were well dug-in positions. An attempt had been made latterly to dig an anti-tank ditch between the rear slopes of Zemlet el Beida and Sebkret en Noual to the north-west, probably as a precaution against another left hook.

Enemy Dispositions

First Italian Army had to rely mainly on Italians to hold the line, while the Germans laced the position at critical points. The line was held by 20th Italian Corps on the east and 21st Italian Corps on the west. 20th Corps had Young Fascist Division on the coast, 90th German Light Division astride the main road, and Trieste Division as far as Djebel Roumana. 21st Italian Corps had Spezia Division on the east and Pistoia Division on the west, with one regiment from 90th German Light Division, and with what was left of 164th German Light Division as reserve. The 90th German Light Division was much concerned about the defence of Djebel er Roumana, which was not in its sector, and did its best to persuade the Italians to strengthen the defences, even to the extent of offering to put a German battalion there. The offer was not accepted, but 90th German Light nevertheless directed one of its regiments to reconnoitre routes to Roumana.

The enemy’s transport situation was acute. The 90th German Light Division was only 50 per cent mobile, and 164th German Light Division had to march on foot back to its existing position in reserve.

But, as usual, Eighth Army’s greatest interest was the whereabouts of the three panzer divisions. The 15th Panzer Division, with only fifteen runners at this time, was in reserve behind 20th Italian Corps, much as at Mareth. The 10th Panzer Division, with fifty tanks, together with a heavy tank battalion of twenty-three tanks and Centauro Battle Group with ten, was opposite the Americans at Maknassy. And 21st Panzer Division with forty tanks was opposing the Americans at El Guettar, 50 miles south-west of Maknassy. The enemy’s armour was thus dispersed, with the greater strength opposite the Americans, but it was all within one night’s travel to any part of the front.

The average strength of the unarmoured divisions, whether German or Italian, was estimated at 4100, and the total unarmoured troops in the Akarit line at 24,500.

However, as with all enemy strength states at this period, the record is insufficient for any degree of certainty. A contemporary estimate for 7 April 1943 puts the strength of 1st Italian Army, including its German element, at 106,000.

2nd NZ Division is Relieved

During 31 March reconnaissance of the enemy position continued, patrols from 21st Battalion bringing back reports of defences with outposts in front. The 23rd Battalion was moved forward to strengthen a somewhat nebulous position, and then 5th Infantry Brigade formed a properly co-ordinated gun line near the main road. The 21st Battalion was on the right of the railway line just west of the road, and 23rd Battalion on the left, the general line of the FDLs being some two miles short of Wadi Akarit. The troops and the guns of 5th Field Regiment moved up after nightfall, and 4th and 6th Field Regiments also deployed, although in some places it was difficult to find good positions. Both Sound Ranging and Flash Spotting Troops of 36th Survey Battery found good sites, and Survey Troop was as usual busy with bearing pickets.

The position was occupied without enemy interference, but in the morning of 1 April it was both shelled and mortared. However, during that time the relief officers from 51st Highland Division arrived to reconnoitre the line, and after dark the relief took place. Fifth Infantry Brigade then withdrew to the west of Metouia. Divisional Cavalry patrols were withdrawn, and the whole Division, including 8th Armoured Brigade, but less the divisional artillery, was now in rear areas. The artillery was to support 30th Corps in its attack, and remained in position.

Plans and Orders

At a 30th Corps conference on 1 April, the Corps’ plan was explained for the first time. The New Zealand Division would not take part in the main attack, but would pass through a gap made by 50th Northumbrian Division, and would not advance until the gap was made. The Army’s final objective was the line Sfax-Faid (codename RUM), but at that stage the situation would be reconsidered, as there should by then be a junction with the Americans. Thirtieth Corps was responsible for a sector from the sea up to and including Djebel Tebaga Fatnassa, with 10th Corps west of that point. The objectives of the attacking divisions were:

51st (Highland) Division—Djebel er Roumana

50th (Northumbrian) Division—the pass between Djebel er Roumana and Tebaga Fatnassa, where a gap was to be made for 2nd NZ Division

4th Indian Division—Djebel Tebaga Fatnassa

The 7th Armoured Division was in reserve. As 2nd NZ Division was to pass through a gap made by 30th Corps, it was under tactical command of that Corps at the outset, but at a suitable time when it was into or through the gap it would revert to the tactical command of 10th Corps.

For the moment 10th Corps was responsible only for the line west of 30th Corps. On the night before ‘D’ day the Corps—in effect 1st Armoured Division and ‘L’ Force—was to make a feint attack by way of deception. The 1st Armoured Division would follow 2nd NZ Division, with the latter responsible for armoured car reconnaissance across the whole Corps’ front until 1st Armoured Division could speed up and position itself on the left.

The right boundary of 10th Corps after the breakthrough was a line parallel to but one mile west of the main road for about 20 miles, and thereafter due north. ‘L’ Force was to relieve 1st British Armoured Division early on ‘D’ day and would then protect the left flank during 10th Corps’ advance, ranging just as far to the west as terrain and resources would permit. The initial objective for 10th Corps was to be the area round Sebkret en Noual, bounded by the line of the railway from Mahares to Mezzouna.

Both the 30th Corps break-in and the 10th Corps break-out were to be closely supported by the Desert Air Force, as an extension of the air attacks on enemy positions, transport and landing grounds which were already going on relentlessly day and night. For 30th Corps’ attack there would be a fighter screen to protect close and concentrated attacks similar to those at Tebaga. Subsequently 2nd NZ Division would have steady air support, on call through four air tentacles. The arrangements included many details for indicating targets and forward defended localities, and for making specified landmarks by letters bulldozed in the sand and blackened with burned petrol tins.

One small point of interest at this time is that the shadow of United States formations falls across Eighth Army, for in many orders, including those of 10th Corps, it was thought better to specify that the British formation was ‘1st British Armoured Division’, as the United States formation round Maknassy was 1st US Armoured Division.

For this operation there was an absolute proliferation of code-names, and one paragraph in a 30th Corps’ instruction reads:

To avoid any risk of duplication or confusion any code names to be used by divs will be restricted to the following types of words:—

HQ 30th Corps – Classical names

CCRA – Birds

7th Armd Div – Biblical names and animals

2nd NZ Div – Food names

50th (N) Div – Girl’s names

51st (H) Div – Scotch place names

4th Ind Div – Games and sports

Army Headquarters used names of drinks, e.g., GIN and RUM; 1st Armoured Division used names connected with horses and harness, while ‘L’ Force used colours.

2nd NZ Division Orders

The operation instruction for 2 NZ Division (No. 14) was not issued until 5 April, and was as usual the culmination of many conferences, discussions and general activities in the period from 31 March.

The order, after recapitulating the details of Army and Corps instructions, then prescribes the order of march through the gap as:

8th Armd Bde less B2 Ech

2nd NZ Div Cav

KDG

Gun Group

5th NZ Inf Bde Gp

Main HQ 2nd NZ Div

B2 Ech Gp

2nd NZ Div Res Gp

6th NZ Inf Bde Gp

1th NZ Amn Coy

Rear HQ 2nd NZ Div

2nd NZ Div Adm Gp less 1st NZ Amn Coy

The 8th Armoured Brigade was to form up on the night before ‘D’ day with its head some five miles short of the anti-tank ditch. For the advance through the gap both Divisional Cavalry and King’s Dragoon Guards were to be under the orders of the brigade, and were to form up and move behind it. The gun group would not be able to form up until it had finished firing in support of 30th Corps’ attack. It consisted of 4th Field Regiment (less a troop with KDG), 64th Medium Regiment, RA, 7th NZ Anti-Tank and 14th NZ Anti-Aircraft Regiments (less detached batteries with groups), 36th Survey Battery and Mac Troop. No moves were initially laid down for the remainder of the Division, although 5th Infantry Brigade Group stood prepared to form up on 6 April ready to move forward.

A special ‘task force’ was to move in rear of 50th Northumbrian Division’s attack, and make and mark three gaps in the minefield ready for the passage of 2nd NZ Division. It was to consist of:

One platoon of engineers from 8th Field Company

One company of infantry from 6th Infantry Brigade

Detachment from Divisional Provost Company

and was to be supported by one squadron of Crusader tanks from 8th Armoured Brigade—all under the command of the CRE, Lieutenant-Colonel F. M. H. Hanson.

This special force was given its duties after discussions with 50th Division by the GSO I and the CRE. Both officers came away somewhat perturbed by the method of getting through a minefield adopted by that division. New Zealand infantry had always gone through in extended line closely following the barrage, but 50 Division’s plan was for each infantry company to be led through the minefield in single file by a sapper, using a mine detector, a procedure which occasioned later delays, but which, nevertheless, was based on much experience.

The divisional instruction laid down the axis of advance, and the action to be taken by the leading troops when through the gap, which amounted to reconnaissance to the north and west while the main body of the Division awaited developments. The only new unit was the Greek Squadron of armoured cars, which had been with ‘L’ Force since February. It came under 2nd NZ Division on 3 April and was placed with Divisional Cavalry.

The order of march given on page 257 shows, quite unobtrusively, what was claimed as a minor victory for the infantry brigadiers, in that 8th Armoured Brigade was to lead off without its B2 Echelon of transport. It had long been a source of complaint that armoured brigades took their excessively long ‘tail’ with them in close support. It has already been recorded that on occasion the next-following formation was either delayed in moving off, or forced into tactical remoteness.

The only special point in the administrative instructions was that all units would hold rations and water for seven days and petrol for a minimum of 300 miles in first-line vehicles, and rations and water for four days and petrol for 100 miles in second line. There were still two RASC companies with the Division to augment the New Zealand companies. As usual, these simple words cover a great deal of planning by the AA & QMG (Lieutenant-Colonel Barrington), and of hard work by the ASC, ordnance and EME units, to ensure that the Division moved off fully stocked.

Artillery

Because of the vital importance of penetration on this front, 2 NZ Divisional Artillery was to support 50 (Northumbrian) Division in its attack. Two of 50 (N) Division’s three field regiments had been left behind at Mareth to help clear up the battlefield, and only one (124 Field Regiment, RA) was available for the battle. In addition, 2 Regiment of Royal Horse Artillery from 1 Armoured Division would help when not required on other tasks, all regiments being under the direction of the CRA 2 NZ Division. The programme included a barrage by the three New Zealand field regiments, fire on selected targets by the other field regiments and by the New Zealand regiments when not engaged in the barrage, and defensive fire tasks by two medium regiments. The 111th Field Regiment, RA, of 8 Armoured Brigade took no part but remained in immediate readiness to advance with its brigade. On the conclusion of the programme 5 and 6 Field Regiments were to join 5 and 6 Infantry Brigades respectively, while 4 Field Regiment and 64 Medium Regiment, RA, joined the gun group.

After the final objective had been gained, one battery from 6 Field Regiment would fire at intervals along a defined line to mark the bombline for the air force.

For the Ammunition Company it was a period of heavy dumpings – 9000 rounds on 1 April, 9164 on 3 April and 2700 on 4 April; by 6 April it had dumped 300 rounds per gun and kept up full replenishment as well. A second company was obviously needed, but the NZASC had to finish the war in North Africa without it.3

Brigade Plans

The 8th Armoured Brigade decided to advance on a one-regiment front with Staffs Yeomanry in the lead, followed by Tactical Headquarters. But as soon as conditions allowed the brigade would move in ‘A’ formation, with 3 Royal Tanks echeloned back on the left and Notts Yeomanry on the right.

On the day of the attack 5 Infantry Brigade Group was to form up in nine columns on the east side of the tracks (nine in number) which the engineers would prepare from the divisional area to the minefield – all moves to be completed by 11 a.m. The order of march would be:

Advanced Guard as before4

Tac HQ

21 Bn Group

5 Field Regiment

23 Bn Group

28 Bn Group

7 Field Company less dets

Main HQ and B Echelon transport

ADS 5 Field Ambulance

Workshops

There was a degree of decentralisation down to battalions more marked than usual, which led to the use of the term ‘battalion group’. Attachments to each battalion were two troops of anti-tank guns, one section of light anti-aircraft guns, and two platoons of machine guns.

Divisional Activities, 1–6 April

The days preceding the attack were reasonably quiet, except for a little harassing fire on both sides. The 50th Division took over the central sector of 30 Corps ‘ front at 8 a.m. on 4 April, with 69th Infantry Brigade in the line. Responsibility for its artillery support then passed to the CRA 2 NZ Division.

The engineers carried on with their usual multifarious tasks – water supply, repairs to demolitions, maintenance of roads – and there were in addition two special tasks intimately connected with the forthcoming operation. One was the preparation and marking of nine tracks, starting three miles south-west of Metouia and ending on a ridge seven miles farther north, beyond which it was not possible to proceed without coming into view of the enemy. This involved much bulldozing and laying of culverts in wadis that now had water in them. It kept 5 Field Park Company and 6 Field Company pleasantly busy.

The second was to prepare for the task of clearing gaps in the minefield. For this purpose 8 Field Company (Major Pemberton5), less headquarters and inessential transport, assembled south-west of Oudref before dark on 5 April. There it was joined by the tank, infantry and provost components.

For Divisional Cavalry and the infantry the few days from 1 to 5 April were restful on the whole. The cavalry was made up to establishment in Stuart tanks and the Greek Squadron came under its wing. All six infantry battalions carried out the usual activities in a rest period – maintenance, reorganisation, conferences, route marches, tactical exercises, swimming excursions where the sea was near enough – and had some real rest.

Enemy air forces were active in this period, although the bombs dropped were nearly all anti-personnel. The results were negligible.

On the other hand, the activities of the Allied air forces far exceeded those of the enemy and in some directions were devastating. The Desert Air Force attacked landing grounds, enemy positions and transport, and farther behind the battlefront the air forces were dislocating the enemy’s air transport system from Sicily and Italy. At the end of March it was estimated that over 100 transport aircraft were arriving in Tunisia every day, but on 5 April forty were destroyed in the air and 188 on Tunisian and Sicilian airfields, a blow that was well-nigh crippling.

General Montgomery visited 2nd NZ Division on 2 April and spoke to all officers and NCOs who could be released from duty; he then moved in turn to Divisional Headquarters, 6th Infantry Brigade, Reserve Group, 5th Infantry Brigade (including KDG and Divisional Cavalry), Divisional Artillery, and 8th Armoured Brigade. On 4 April General Freyberg paid a special visit to 8th Armoured Brigade and spoke to the officers of all three regiments, for he – and others in 2nd NZ Division – had much regretted that in press references to the Division the British formations and units under command had not received their due credit. The visit was much appreciated, for all units gave it a special ‘write-up’ in their war diaries.

The Attack at Akarit

In the 30th Corps ‘ plan of attack 4th Indian Division, probably the body of Allied troops best trained in mountain warfare, planned its own attack within certain specified limits of time and place. To obtain the advantage of surprise the division began by attacking, without artillery support, the southern peak of the Djebel Tebaga Fatnassa massif immediately after dark on 5 April. This peak, the commanding ground, was soon taken, and the division went on to capture both Djebel Mesreb el Alig and Djebel el Meida, a magnificent night’s work that earned both the admiration and the awe of the rest of Eighth Army. By 9.30 a.m. on 6 April the left flank had triumphed and some 3.000 prisoners had been taken, nearly all from Spezia and Pistoia Divisions. Two counter-attacks had been beaten off, and the mixed German and Italian troops were never allowed to recover from the audacious and successful assault.

At 4 a.m. on 6 April the artillery throughout 30th Corps began their tasks. All told, there were eighteen field regiments and four medium regiments, a total of 496 guns. From a forward observation post the effect of this weight of artillery was most impressive – overhead a constant sighing as the shells went over, to the rear bright and continuous flashes, to the front a constant crashing of shells, and pervading all the numbing detonation of the guns. The effect on the enemy’s side must have been great.

On the right flank 51th (H) Division reached Djebel er Roumana by 6 a.m., and by 11 a.m. reached the north-west end of the anti-tank ditch beyond, which was a point on the final objective. This was held after a struggle. One battalion from Trieste Division was eliminated, and prisoners were taken from 90 Light Division, one regiment of which counter-attacked at 9 a.m. and for a while held 51st Highland Division, but was in turn driven back.

In the central sector – 50 (N) Division – the minefield and anti-tank ditch formed a genuine obstacle, and the enemy resisted strongly any attempts to cross. By 5.30 a.m. a footing was made towards the seaward end, but further penetration was stopped.

During the rest of the day both 51st Highland and 4th Indian Divisions reached their final objectives. The enemy counter-attacked again at 4 p.m., this time with 15th Panzer Division from reserve, and forced 51 Division back slightly, although not enough to affect the satisfactory position on the right flank. The 4th Indian Division had some hard fighting with yet another regiment from 90th German Light Division, but held all its gains. In his despatch on the campaign General Alexander says of this day that ‘15 Panzer and 90 Light Divisions, fighting perhaps the best battle of their distinguished careers, counter-attacked with great vigour and by their self-sacrifice enabled Messe to stabilise the situation.’ The desperate efforts of these two divisions to stop up the holes in the front irrespective of where the holes occurred can only excite our admiration. Certainly Montgomery described the fighting as having been ‘heavier and more savage than any we have had since Alamein.’

During the day the Desert Air Force maintained unceasing attacks against transport, gun positions and troop concentrations, but could find few tanks and claimed only one destroyed.

Owing largely to the success of 4th Indian Division in clearing the heights on the left flank and discovering a passable track through the hills so as to avoid the anti-tank ditch which was still delaying 50th (N) Division, Horrocks persuaded the Army Commander to order the advance of 10th Corps. Tanks did in fact move up to the 4 Indian Division area, but guns from the rear of Roumana, firing obliquely, prevented any move forward. But 10th Corps was now taking part in the battle, and 2nd NZ Division passed to its command at 11.10 a.m. Until the situation on Roumana, scene of many counter-attacks, was clarified, and the offending guns, probably 88-millimetres, silenced, a further advance depended upon the success of 50th (N) Division.

This division had advanced shortly after 4 a.m. At 5.30 a.m. the gap-making force from 2nd NZ Division moved forward some miles and there waited while the CRE and the second-in-command 8th Field Company (Captain Wildey) went to reconnoitre. When they reached the centre of the position they found that 50 Division was baffled by the minefield and anti-tank ditch and was not taking any special action to overcome the difficulty, but had transferred activity to the ends of the ditch.

The CRE decided to proceed at once with the task of lifting the mines and filling in the ditch, over which two crossings for tanks were to be made. He called forward the supporting tanks and infantry by wireless and ordered the tanks to keep close watch on enemy activities, especially on the mortar and machine-gun posts that covered the ditch. Major Pemberton started his company clearing gaps in the minefield, removing booby traps and trip-wires. D Company, 26th Battalion (Captain Hobbs), then moved through the minefield, some men taking up positions on the far side of the ditch, while the remainder set to work to fill in the crossings for tanks. It was now about 9.30 a.m. and reports on the state of the work were wirelessed back to Divisional Headquarters. Infantry of 50th Division was now mopping up enemy posts across the ditch and so helping to reduce the volume of fire.

This comparatively slow rate of progress led the GOC to consider taking the Division round the east side of Djebel er Roumana, and up to 11 a.m. he was still undecided. Divisional Cavalry was sent forward on a reconnaissance over the country leading to the east of Roumana, but as the going was not favourable and obvious complications would arise from such a change of axis, it was decided to adhere to the original plan.

One crossing over the ditch was open by 2 p.m. and the second not long after; but there was still considerable opposition from the enemy. It was the generally aggressive attitude of the little gap-making force, the watchfulness of the tanks and infantry and the determination of the engineers that enabled the work to be done at all.

Meanwhile 50th (N) Division, finding enemy resistance strong in the centre, had concentrated on the flanks, and the climax came when infantry supported by tanks from 7th Armoured Division forced their way across near Point 85, the right-hand end of the obstacle, and followed this with an attack westwards along the far side of the ditch.