The Battle of the Duisburg Convoy, also known as the Battle of the BETA Convoy, was fought on the night of 8/9 November 1941 between an Italian convoy, its escorts and four British ships. The convoy was named “BETA” by the Italian naval authorities and carried supplies for the Italian Army, civilian colonists and the Afrika Korps in Italian Libya. The name “Duisburg Convoy” refers to the largest ship.

Force K of the Royal Navy, based at Malta, annihilated the convoy, sinking all the merchant ships and the destroyer Fulmine with no loss and almost no damage. The Maestrale-class destroyer Libeccio was sunk next day by the British submarine HMS Upholder, while picking up survivors.

The Italians were severely criticised by the German naval attaché and pressured to accept liaison officers at Supermarina (headquarter of the Regia Marina) and on its ships. Italian attempts to reduce the risk of interception by British forces, by sending individual ships, pairs and smaller convoys from several ports at once was futile, because the British were reading Italian naval codes; the next convoy was forced to return to port.

In early November 1940, the Italian offensive in Greece had been defeated and the Italian battleships Littorio, Conte di Cavour and Caio Duilio had been damaged at the Battle of Taranto. The ship losses of the Italian Fleet had made it easier for the British to supply Malta and Greece. The Axis forces involved the Western Desert Campaign were supplied across the Mediterranean by convoys from Italy to the ASI. Tripoli was the main entrepôt of the colony, which had lesser ports to the east, including Benghazi. The normal route for Italian supply deliveries to Libya went about 600 mi (966 km) westwards around Sicily and then close to the coast of Tunisia to Tripoli, to avoid interference from British aircraft, ships and submarines based at Malta. In Africa, supplies had to be carried huge distances by road or in small consignments by coaster. The distance from Tripoli to Benghazi was about 650 mi (1,050 km)

Duisburg (BETA) Convoy operation

The convoy consisted two German vessels, SS Duisburg 7,889 gross register tonnage (GRT) and SS San Marco (3,113 GRT) and the Italian MV Maria (6,339 GRT), SS Sagitta (5,153 GRT) and MV Rina Corrado (5,180 GRT), carrying 389 vehicles, 34,473 long tons (35,026 t) of munitions, fuel in barrels and troops for the Italian and German forces in Libya. The tankers Conte di Misurata (7,599 GRT) and Minatitlan (5,014 GRT) carried 17,281 long tons (17,558 t) of fuel.[11] A powerful escort was to arranged for the convoy operation to counter the British flotilla recently based at Malta.

Close Escort (Captain Ugo Bisciani)

Maestrale-class destroyers :

Maestrale

Grecale

Libeccio,

Folgore-class destroyer

Fulmine (capitano di corvetta Mario Milano)

Turbine-class destroyer

Euro (capitano di corvetta Giuseppe Cigala Fulgosi)[14]

Oriani-class destroyer

Alfredo Oriani

Distant Escort (Vice Admiral Bruno Brivonesi)

3rd Cruiser Division: Trento-class cruisers : Trieste and Trento

13th Destroyer Flotilla Soldati class destroyers :

Granatiere

Fuciliere

Bersagliere

Alpino

Italian destroyer Fulciliere

The convoy was routed to the east of Malta, since the airfields in Libya were under Axis occupation, rather than the usual west and along the Tunisian coast. The convoy speed was 9 kn (17 km/h; 10 mph) and the distant escort had to sail a zig-zag course at 16 kn (30 km/h; 18 mph). Brivonesi and Supermarina were under the impression that the British ships would not be able to attack because they overlooked radar and prepared only for night attacks by aircraft.

Force K

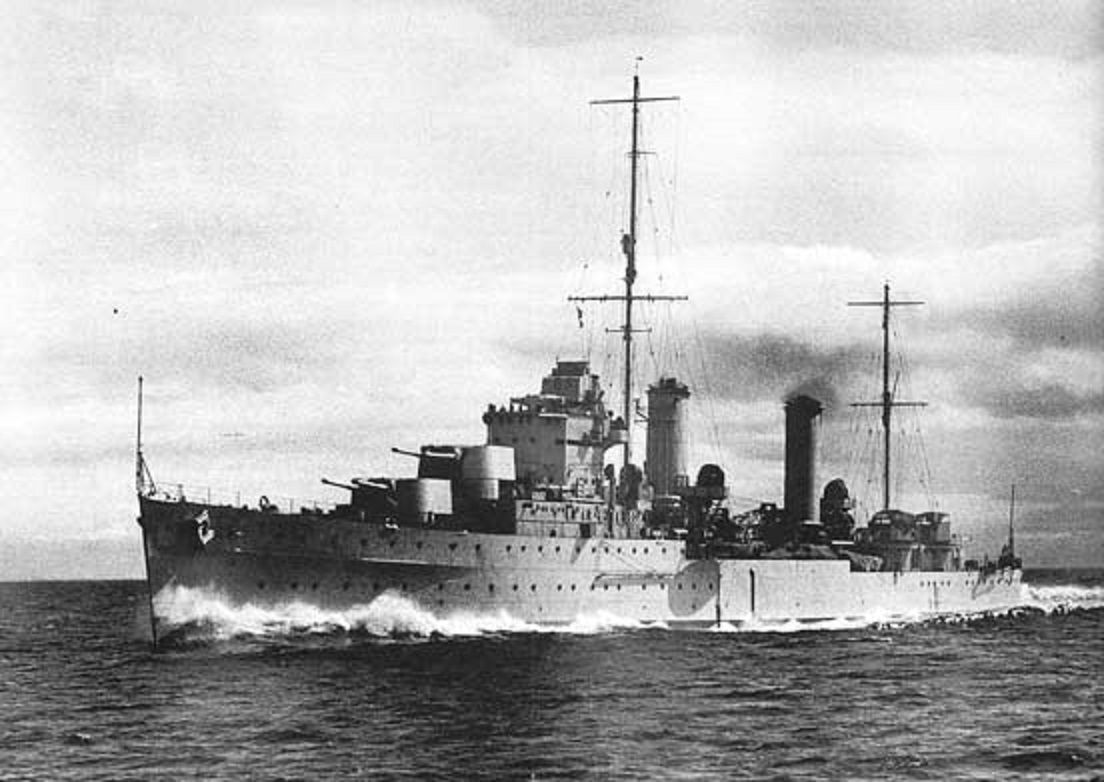

Force K (Captain William Agnew) consisted of two light cruisers with six 6-inch guns in twin turrets each and two treble 21-inch torpedo tubes. Two destroyers from Force H with four twin 4-inch guns each and two quadruple 21-inch torpedo tubes, joined Force K at Malta. Intended to fight at night, all of the ships were equipped with radar and the cruisers had new searchlights with better performance.

Arethusa-class light cruisers :

HMS Aurora (flagship)

HMS Penelope

HMS Penelope

L-class destroyers

HMS Lance

HMS Lively

HMS Lance

The Duisburg (BETA) Convoy, the 51st German–Italian sailing since 8 February, departed from Naples on 7 November and Force K sailed the next day, forewarned by the British success in reading Italian cyphers concerning Axis shipping movements in the Mediterranean. A British reconnaissance aircraft was dispatched to “find” the convoy as camouflage

8/9 November 1941

Force K made 28 kn (32 mph; 52 km/h) north-east of Malta, with HMS Aurora leading the ships in line-ahead. The main convoy was found around midnight about 135 mi (117 nmi; 217 km) east of Syracuse. There was slight moonlight to the east and the British ships took up position with the moon silhouetting the convoy. Captain Agnew was under instructions to attack the nearest escorts first and then fire on the convoy, dealing with the other escorts as they appeared. The British ships slowed to 20 kn (23 mph; 37 km/h) and the gun crews were ordered to fire steadily, volume of fire being less important than accuracy. As the ships closed with the convoy, radar detected more ships, assumed to be destroyers and escorts but actually the distant escort (scorta a distanza). Force K sent an attack signal at 12:47 a.m. which was received by Trieste but jamming from Lively prevented a warning reaching the convoy; the only ships aware of the attack were 9.2 nmi (11 mi; 17 km) away.

Aiming by radar, the British opened fire at about 12:58 a.m. from a range of 5,200 yd (2.6 nmi; 3.0 mi; 4.8 km) down to 3,000 yd (1.5 nmi; 1.7 mi; 2.7 km). Grecale was hit by the first three salvoes from HMS Aurora; HMS Lance and the 4-inch secondary armament of HMS Aurora bombarded a merchant ship. HMS Penelope engaged Maestrale, the leader of the close escort (scorta diretta) and was on target with the first salvoes and HMS Lively began to shell the merchant ships three minutes afterwards. At first, the Italians thought that they were under air attack and the wireless mast of Maestrale was hit. Fulmine attacked but was soon severely damaged by British gunfire, Captain Milano losing an arm but remaining in command until the ship sank. Grecale was hit and came to a stop outside torpedo range and was later towed back to port by Oriani. Euro, undamaged, came within 2,200 yd (2,000 m) of the British ships but mistook them for Trieste and Trento, aided by the ships not firing on Euro and because Maestrale had been signalling for Italian ships to rally on the port (far) side of the convoy, leading to Cigala countermanding an order to launch torpedoes. Moments later, British ships opened fire but Euro was no longer in a position to attack with torpedoes. Six British shells hit Euro but at such short range they passed through without exploding, killing about twenty members of the crew.

The distant escort was on the right hand side of the convoy, steaming twice as fast, zig-zagging to keep station and also thought that the convoy was under air attack. At 1:13 a.m. Brivonesi signalled to Supermarina that torpedo bombers were attacking and then sailed for the point where the British ships had first been sighted instead of their current position. When watchmen on Trieste saw the arc of shells and ships beginning to burn, the distant escort was about 5,000 yd (2 nmi; 3 mi; 5 km) distant at the end of its zig-zag away from the convoy. As the escort closed on the convoy the British ships moved beyond the glare of the fires and became much harder to identify. Trento fired star shells, then both Trieste and Trento opened fire at the British ships at 8,700 yd (4 nmi; 5 mi; 8 km). From 1:10 to 1:25 a.m. the British engaged the Axis merchant ships with shell and torpedo, the ships taking little evasive action. The close escort on the east side of the convoy moved off with Maestrale and Euro to rally and then attacked again, the Italian salvoes having no effect and the ships then being driven off. The distant escort sighted the British again and fired 207 8 in (200 mm) rounds, managing to straddle some of the British ships. The fires and explosions on the merchant ships obscured the British ships and Brivonesi ordered the distant escort to turn north at 24 kn (28 mph; 44 km/h) to intercept them but made no further contact. Some shells had landed close to British ships as they finished off the convoy but caused only splinter damage to HMS Lively’s funnel; by 1:40 a.m. firing has ceased.

Italian destroyer Libeccio sinking on 9th November 1941

9 November 1941

All of the Axis merchant ships had sunk or were sinking and on fire. Force K , the British task force headed at high speed towards Malta at 2:05 a.m. being ineffectively chased by the covering force, not noticing Italian salvoes at 2:07 a.m. and reached harbour at Malta by 1:00 p.m. that afternoon. Force K had sunk about 39,800 long tons (40,439 t) of Axis shipping. The destroyer Libeccio was torpedoed by the submarine HMS Upholder while rescuing some of the 704 survivors of the BETA Convoy. Libeccio was taken in tow by Euro and after an internal structural collapse, sank. The Italian cruisers were also looking for survivors and managed to evade torpedoes.

Analysis :

In 1948, Marc’ Antonio Bragadin wrote that the battle was a serious Italian defeat, in which individuals had shown exemplary bravery but the escorts had lacked coordination and made mistakes because of the confusion caused by the surprise and speed of the British attack and mistaken identity. The Italians had no answer to the superior British night-fighting equipment and tactics which had revolutionised maritime night fighting. Technical obsolescence made an Italian attempt to counter the British at night a useless sacrifice of crews and ships. Writing in 1957, the British official historian of the Royal Navy, Stephen Roskill, wrote that morale in the Regia Marina suffered greatly after such a formidable escort had failed to prevent the disaster. Next day, Rommel signalled to Berlin that convoys to the ASI has been suspended and that of 60,000 troops due in Benghazi, only 8,093 had arrived. In 1960, Ian Playfair, in volume III of "History of the Second World War, The Mediterranean and Middle East, the official British campaign history, wrote that the destruction of the Duisburg (BETA) Convoy was a severe blow to the Axis forces in Cyrenaica. Some supplies arrived in ships sailing alone or in pairs, more journeys were undertaken by submarine and fuel was carried by warships. Fewer convoys with more escorts and air cover were planned and four convoys sailed on 20 November.

In 2002, Jack Greene and Alessandro Massignani wrote that the German naval attaché, Admiral Werner Löwisch, criticised Italian night fighting training, noting that of his 150 training sessions on the cruiser Leipzig, 130 had been at night. Italian ships had no night fighting equipment like low-light rangefinders and torpedo boats (escort destroyers in British parlance) could not engage targets further out than 10,000 yd (6 mi; 9 km). In a report to Berlin, Weichold blamed a lack of training and accused Brivonesi of incompetence. In retrospect the Italians had erred in assuming that a night attack by ships was unlikely; merchant ships should have been instructed to scatter or sail away from an attack. The destroyers on the port side should not have withdrawn but attacked at once without regard for the risk of friendly fire and the distant escort should have estimated the position of Force K instead of heading towards the sighting, attacking the British as they sailed for Malta. Brivonesi was court-martialled and sacked for not attacking (and reinstated on 5 June 1942).