The Pittsburgh Press (December 15, 1943)

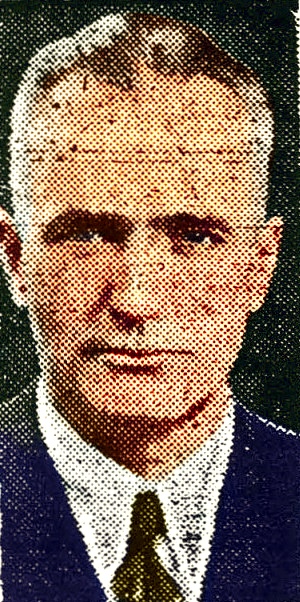

Maj. Williams: Tactics

By Maj. Al Williams

With 1943 nearing its end, some observations on the tactics of modern warfare are appropriate.

Thus far, no hostile forces have breached the final Nazi eastern line within hundreds of miles of Germany proper. Huge armies are not pounding Germany from a west front. There is a front in Italy, but that’s not near enough to Germany to make its pressure felt within that nation.

In other wars, with an enemy nation surrounded, and cut off from sea traffic, it would have been possible to starve out the belligerents by sea and land blockage. But unlike the last war where blockage was steadily and inexorably starving the German war effort while great Allied armies pounded and hacked at its heart, we now find the combat fronts far from Nazi boundaries. And the Germans apparently have sufficient food and supplies.

Nevertheless, we are told – and rightly – that affairs within Germany are bad. What has upset the carefully regimented and planned Nazi war strength? Day and night hammering from the air. There’s not a spot within Germany that cannot be and is not reached and stabbed by Allied bombers – night and day.

There’s no way of estimating just what the constant air threat represents in the loss of man hours of labor to German war production. It’s true that the Nazis, in anticipation of being bombed, scattered their production units. Against this safety precaution must be debited the extraordinary transportation burden of carrying the products of each factory to some common center for assembly. Naturally, the Allied airmen, keenly aware of this transportation problem, have been persistently hammering away at the German railroads. This air pressure on the German rail transportation system must represent a vital faction in the eventual breakdown.

Occasionally we hear complaints about the shortage of rail passenger accommodations in this country with our roadbeds and rolling stock untouched by explosives. Just imagine what the general rail situation must be in Germany.

Then, too, consider the constant threat of air bombardment and its effect upon the dislocation of factory routine. Just assume for a moment what would happen to the grand totals of planes and engines produced by Pratt & Whitney, Grumman, Republic and Wright Aeronautical if these factories were being systemically bombed day and night. I think it would be safe to assume that none of them would be attaining better than one-half their current production. The cities of the Ruhr are no longer places conductive to the all-essential rest and eight-hour sleep of war workers. And now as the air-raid network is expanded, the same can be said for almost all important German cities. Many one-time important Nazi cities are nothing but shells, unfit for normal habitation. And, remember, sleep is equally important as food for physical fitness and wellbeing. Deficiency in food or sleep has its direct reflection in depreciated morale.

These are the things the Allied air arms are doing to the German war effort and German morale. By no means do I mean to infer that air bombardment alone will win this war and force surrender of the Nazi outfit. But I do maintain that the day-and-night bombardment of Naziland will be the pressure that will finally break the backbone of the Germans in this war, as the sea blockade broke them in the last war.