894.00/1111: TelegramThe Ambassador in Japan to the Secretary of State

Tokyo, October 18, 1941 — 4 p.m. [Received October 18 — 5:36 a.m.]

1652.The composition of the Tojo Cabinet was announced this afternoon as follows:

Prime, War and Home Ministers: Lieutenant General Hideki Tojo; Foreign and Overseas, Shigenori Togo; Finance, Okinori Kaya; Navy, Admiral Shigetaro Shimada; Justice, Michiyo Iwamura; Education, Kunihiko Hashida; Agriculture, Hiroya Ino; Commerce and Industry, Shinsuke Kishi; Communications and Railways, retired Vice Admiral Ken Terashima; Welfare, Surgeon General Chikahiko Koizumi; Without Portfolio, Lieutenant General Teiichi Suzuki.

GREW

894.002/502Memorandum by the Chief of the Division of Far Eastern Affairs

Washington, October 18, 1941.An Estimate of the Tojo Cabinet

The recently formed Japanese cabinet under the premiership of General Tojo appears to be a strong cabinet, predominantly military in character and with a large representation from among military leaders who have been directly involved in Japan’s program of aggression on the continent. It is believed that the new cabinet will emphasize in its policies military preparations, further mobilization of the national strength, and deployment of military forces and equipment on the perimeter of Japan’s defense areas.

Politically, the most important problem facing the new cabinet remains the settlement of the “China incident” and relations between Japan and the continent. Economically, the most important problem remains the securing of basic commodities, in particular oil and ferrous metals, and the breaking of the economic and commercial measures in restraint of Japan by the ABCD powers. Militarily, the most important problem remains the threat of hostilities with the ABCD powers, plus the grave danger of military cooperation between the United States and Soviet Russia against Japan.

It is not believed that the new cabinet will reject a negotiated solution of Japan’s international relations, but at the same time will take every measure possible to insure that, if such negotiated solutions are not forthcoming or are not successful, the opportunity for a solution by force will not be lost through lack of preparation or deployment of forces. It is probable that the Japanese Government will seek to recover an “autonomous” position in order to be able to take advantage of events or offers in negotiations.

The new Foreign Minister, Mr. Togo, is a career diplomat who has served as Ambassador both to Germany and the Soviet Union. His wife is German. It is reported that he has had unfriendly relations with former Foreign Minister Matsuoka but that he has maintained cordial relations with other Japanese who have favored cooperation between Japan and Germany. Mr. Togo, prior to his assignment as Ambassador at Moscow, was characterized as anti-foreign and particularly anti-American. However, his relations with Ambassador Steinhardt and the staff of the American Embassy at Moscow while he served as Japanese Ambassador there were marked by special cordiality. Mr. Togo’s reputation is that of an experienced, patient and capable negotiator. His appointment does not rule out hostilities between Japan and Russia and/or the United States, but at the same time it would appear to indicate that the Japanese Government may have in mind continued efforts towards a negotiated settlement with the United States and with Russia.

MAXWELL M. HAMILTON

711.94/24068/11Memorandum by the Chief of the Division of Far Eastern Affairs to the Secretary of State

Washington, October 18, 1941.Mr. Secretary: We have given special thought to the question whether there are steps which this country might take in relations with Japan which, while preserving the integrity of this country’s principles, would indicate that relations between the United States and Japan are being maintained. We now offer for consideration various suggestions, as follows:

We might offer to charter Japanese merchant ships. We might give Japan in exchange cotton and commodities of non-military use, such as tobacco, medicines, pharmaceutical supplies, foodstuffs, wheat, flour, fertilizers, et cetera; also make payments on Japanese bonds in the United States.

We might offer to furnish Japan steel to build ships for the United States, furnishing the steel on a graduated scale as ships are completed and delivered. An alternative of this would be to give Japan steel in exchange for Japanese ships, or a combination of these two possibilities.

We might examine the possibility of setting Japanese factories to work for our needs.

We might examine the possibility of effecting barter arrangements in incidental, non-military commodities, involving on the American side commodities such as cotton, tobacco, medicines, pharmaceutical supplies, foodstuffs, wheat, flour, fertilizers, et cetera, and on the Japanese side commodities such as tea, lacquer ware, pyrethrum flowers, et cetera.

The Counselor of our Embassy at Tokyo might be accorded the rank of Minister. This might serve as an indication to Japan that the United States regarded its relations with Japan as of unusual importance.

The instructions issued by the Navy Department to American naval vessels in the Pacific should be revised or interpreted so as to permit immediate resumption of the calling of American ships at Far Eastern ports now on their schedules.

Some prominent Americans, such as Mr. Thomas Lamont, Mr. Bernard Baruch, or Senator Thomas, might go to Japan on a special visit.

We might try to arrange for the sending of a professional baseball team to Japan.

MAXWELL M. HAMILTON

740.0011 P. W./570: TelegramThe Ambassador in the United Kingdom to the Secretary of State

London, October 18, 1941 — 4 p.m. [Received October 18 — 3:45 p.m.]

4979.For the Secretary and Under Secretary.

A high official of the Foreign Office today handed an Embassy official the following memorandum of a plan for quick communication in the event of an emergency in the Far East, the need of which was realized following the staff talks at Singapore. He expressed the hope that we would place a corresponding plan into effect without delay:

In the present situation in the Far East a threat from Japan might easily develop with very little warning and it is not possible to determine in advance what type of action by Japan would necessarily call for military counteraction. The British authorities concerned have accordingly been studying the problem of reducing to a minimum the delay which might be caused in such an eventuality by the necessity of intergovernmental consultation. A further problem has been to ensure that all British authorities concerned are simultaneously and immediately warned when a dangerous situation arises.

The procedure which has been devised is outlined below. It is intended to be brought into immediate effect should any one of the authorities concerned receive information indicating that Japan is about to take or has taken action which in his view may necessitate immediate military countermeasures. The authorities in question are the four Commanders in Chief, i.e., Far East, China, East Indies and India; the Governors of Burma, Hong Kong, and Fiji; His Majesty’s representatives at Tokyo, Chungking, Shanghai, Bangkok, and Washington.

In the eventuality contemplated, any such authority would at once telegraph, by the quickest possible method, a code word of warning to London. He would follow this preliminary warning by a second telegram reporting the facts on which he considered it necessary to base his warning.

Any telegram sent under the above procedure would be repeated by the sender to all the authorities enumerated in paragraph 2 above and also to the Governments of Canada, New Zealand, the Commonwealth of Australia, and the Union of South Africa.

Special arrangements have been made in London for any telegram sent under this system to be immediately dealt with by the highest political and military authorities.

His Majesty’s Governments in the Dominions are being invited to introduce analogous arrangements.

On the receipt in London of telegrams of the nature contemplated in paragraph 3 above, the Foreign Office will notify both the United States Ambassador and the Netherlands Government by the speediest possible means.

It is hoped that the United States and Netherland authorities will be willing to consider the introduction of corresponding arrangements whereby any information of threatening action by Japan which the United States or Netherland authorities in the Far East may receive may be immediately communicated not only to London but also on a basis of reciprocity to the British Commander in Chief Far East through the most appropriate channel.

It is emphasized that the procedure proposed is merely one of urgent reporting. A decision as to action must, of course, lie with the Governments concerned.

WINANT

740.0011 European War 1939/16775The President of the Philippine Commonwealth to President Roosevelt

Manila, October 18, 1941.My Dear Mr. President:

Today’s press reports seem to point strongly to the possibility of actual involvement of the United States in the war on account of the torpedoing of the destroyer Kearny. On the other hand, the course of recent events in Japan is far from encouraging to those who would hope that there may not be armed conflict between the United States and Japan. Should this unfortunate situation arise, it is but natural to expect that the Philippines will be the scene of such a conflict. I am, therefore, hastening to reiterate to you what on former occasions I have asserted, namely, that our government and people are absolutely and wholeheartedly for you and your policies, and that we are casting our lot with America no matter what sacrifices such determination may entail.Mr. President, since at a time such as this it is of the utmost importance that the Government of the Philippines should have complete understanding and cooperation with the military and naval authorities of the United States, I believe you will be pleased to know that General MacArthur and I are in perfect accord, and that the government and people of the Philippines are placing at his disposal everything that he needs to accomplish the great task of defending the Philippines. I could almost say as much regarding my relations with Admiral Hart, although, owing to the nature of the Navy’s work, our connections are not so close and our contacts so frequent as those I have with General MacArthur.

Mr. President, it is, of course, a dreadful thing to contemplate the horrors of war, but there is this consideration in which I almost find cause for rejoicing that such an awful situation should arise before the severance of the political ties now existing between the United States and the Philippines; and that is, because the Filipino people are thereby afforded the opportunity to prove in supreme efforts and sacrifices not only our deep appreciation of the great things which America has contributed in the upbuilding of this new nation of ours, but also the fact that the democratic ideals of the United States have become our sacred heritage, and that to preserve such a precious gift we are willing to pay the price in blood and treasure.

With assurances [etc.]

MANUEL L. QUEZON

711.04/254010/35Memorandum by Bishop James E. Walsh, Superior General of the Catholic Foreign Mission Society of America

1. Story.The October 2 reply from Washington shook the confidence of the entire Japanese Government.

With some difficulty the protagonists of peace in the Japanese Government (Prince Konoe, General Mutō and their associates) had held Cabinet, Army, Navy and all the other elements in line, or at least in quiescence, pending the conclusion of the negotiations. All through these negotiations, many have naturally been restive, anxious and suspicious, afraid the Government was being duped and deceived, fearful that it would end up with nothing to show for its efforts but time and strategic opportunity lost — and this was particularly true of the younger and more pushing elements in the Army. The Nazi agents did much to encourage this point of view and the Nazified officials in the Army and Foreign Office contributed their share also. However, the older heads and actual leaders of the Army continued to repose confidence in the peace party under the leadership of Prince Konoe, while reminding him that this confidence was growing thin and must soon evaporate completely unless some substantial results were speedily forthcoming.

The Japanese army is very much imbued with the theory that it is directly responsible to the Emperor and the country for the national defense and any other necessary military implementation of vital national policy, and for this reason its leaders exert great influence on the government when measures are mooted or adopted which seem in their view to render the discharge of this responsibility difficult or impossible.

One reason why the army has remained docile in the present instance is because the nature of the proposed agreement is such as to render their task, not difficult, but easy. They have not feared the success of the plan, but its failure. They have not looked upon it as a check to their aggression (of which they have presumably had enough), but they have feared the danger of deception which would result in bequeathing to them a difficult military job to be performed at a disadvantage.

Many, both in the civil government and the army, now think that the deception goes back to the beginning, that is to say, that the American Government wanted only to draw them out in order to gain time, and to get a statement of their policy in order to condemn it.

All without exception were mystified and chagrined when the October 2 reply harked back to a discussion of general principles. The Japanese officials believed that they had already agreed on the general principles applicable to the situation. Subsequently they were told that they must in addition define specific details. With reluctance, at the risk of compromising the whole negotiations, and not without grave danger to their own lives, they forwarded their September 22 statement which embodied all the precision on details that they dared entrust to the cables. Washington’s response to this was a return to principles. They liked the courteous and kindly tone of the Washington message (October 2) and they understood its thesis about the desire to agree on principles that would not be weakened by exceptions, but they found this chill comfort. The practical effect of the message was enormously discouraging. It put them back at the starting point, facing them with the prospect of reopening the entire discussion ab initio. At such a late day this looked like an indication that Washington was merely fencing and had no intention of concluding any agreement at all. After the receipt of this message, it was very difficult to make anyone in the Japanese Government believe in the sincerity of the American Government, although I was later advised that the leaders of the Cabinet would continue to repose confidence in the sincerity of the President and Mr. Hull, in spite of all appearances, as long as the door was not actually closed to the possibility of reaching an agreement.

At this juncture I took the liberty, at the suggestion of Prince Konoe’s advisers and with the approval of our own Embassy, to ask that my observations on this critical situation be forwarded to Washington. It was universally felt that unless some substantial sign of serious intention on the part of the American Government should promptly materialize, the existing Japanese Government would not be able to hold the position any longer.

The next day, I was asked by Prince Konoe’s advisers if I would go to Washington and explain the present situation of the Japanese Government together with their desires and hopes and fears in regard to the proposed agreement. This I was at first reluctant to do. After some urging I finally consulted the Embassy, where the proposal met with the immediate approval of Mr. Grew and Mr. Dooman. That same evening (October 14) I visited Prince Konoe at his residence and received from him a personal viva voce message to be conveyed to President Roosevelt. The next morning I left Tokyo for Washington.

Two days later, the Japanese Cabinet was changed. This surprised nobody in Japan. I have since been advised that this shift of personnel does not appreciably alter the attitude of the Japanese Government towards the negotiations. I believe this view is the correct one. After the Cabinet change, I received the following telegram from Mr. Paul Ikawa, a close personal friend of Prince Konoe who has been employed by him as a confidential agent throughout these negotiations:

Bon voyage with flowers (code word meaning with the concurrence of General Mutō) no substantial change urgently require speedy response to avoid worst.

I take this to mean that the new Cabinet is maintaining the same essential position in regard to the negotiations and is deferring any other incompatible plans it may have in the hope of yet obtaining an agreement that will establish peace.

It is known that the new Cabinet was formed by Count Arima and Marquis Kido, like many of its predecessors. These two men are supposed to be the two most powerful figures in Japan, barring nobody, and they have been the sponsors of the peace overtures from the beginning. The retention of General Suzuki as head of the Planning Board in the new Cabinet is also significant, as he has been Prince Konoe’s most trusted adviser and general right-hand man throughout all the peace negotiations. General Tōjō, the new Prime Minister, has long borne the reputation of being a conservative, with little if any tinge of the firebrand.

If I were asked to interpret the meaning of the Cabinet change, I would surmise that it means a shift in attitude rather than a change in policy. It is a signal that some definite move is imminent, but that its direction will depend on the circumstances that the immediate future will reveal. It seems to say: We still want peace, but if we are to have it, it must come without further delay. We cannot wait any longer. Therefore we are putting our house in order to move in the other direction, if necessary. Much as we want peace, we must have a prompt and definite decision. Please speak, and speak quickly.

2. Message.On the evening of October 14, Prince Konoe invited me to the Prime Minister’s residence in Tokyo and gave me the following verbal message for President Roosevelt.

From the beginning of these negotiations I and my Government have had nothing but a sincere and wholehearted desire to conclude an agreement that would result in the peace of the Pacific and we have worked very hard to bring this about.

I regret very much the delays and misunderstandings, some of them due, I believe, to the maneuvers of Third Powers, that have operated to retard the negotiations and render difficult the attainment of their important aim.

I still entertain hope of a successful issue, and I will continue to work for the attainment of the object sought, namely, an agreement that will establish friendly relations between our two countries, restrict the scope of the war, pacify and stabilize the Pacific region, and contribute to world peace. And now that the terms have been discussed as completely as is practicable under present conditions, it is my confident belief that a meeting between the heads of the respective governments would readily bring about a completely satisfactory understanding that would insure the great objectives we mutually seek.

I do not quote the Prince verbatim, as I did not take down his exact words at the time they were uttered. I fixed them in my memory, however, and jotted them down almost immediately after the interview. I am satisfied that I have reproduced here the exact sense of his message and even to a large extent, his very words.

3. Attitude.Apart from relaying the message of Prince Konoe, my only commission was to explain the present attitude of the Japanese Government towards the negotiations. I have tried to throw some light on it in these and the pages that follow. However, I can sum it up here for all practical purposes in very short compass. It is that the Japanese Government will not take the responsibility for rupturing the negotiations by sending an ultimatum, but that they believe they have discussed terms to the extent and for the time reasonably possible, that they think they have agreed on the essentials that amply justify a meeting, that they are hurt at the distrust implied in declining a meeting, that they still ardently desire a meeting, and that they can wait no longer for a meeting, but failing its prompt materialization will conclude that they have been hoodwinked, and will proceed almost immediately with the military and naval plans that constitute their only alternative to a meeting.

The nature of these alternative plans I do not know. Nothing was communicated to me in that connection. I think I cannot complete a description of the present attitude of the Japanese Government, however, without reporting that its representatives plainly expect that these plans would lead Japan into a war, eventual or immediate, with the United States.

Does this mean that if a meeting is not promptly arranged, on the basis of the terms already agreed upon and without further specification as to detail, the Japanese Government will abandon the negotiations at once and proceed with other plans?

Substantially that is what I was given to understand, but with one important reservation. The reservation is that the Japanese Government will be glad to consider once more — and once more only — any set of terms or conditions the American Government may declare essential prerequisites to an agreement and/or a meeting, provided they are specific, complete, final, and prompt.

4. Summary.I report therefore three things: (1) That the October 2 message reduced the Japanese Government to desperation, (2) the plea for a belief in the sincerity of the Japanese Government contained in the message of Prince Konoe, and (3) the fact that the Japanese Government can negotiate no longer, but must now have either a decision as to an agreement and/or a meeting, or at least a set of concrete and final terms on which it can itself exercise a decision.

If this is thought to be an insubstantial piece of information to bring across the Pacific Ocean, I can only say that I thought the same myself, and that I would not have troubled to bring it except for the urging of Prince Konoe and his associates coupled with the approval of the American Embassy.

Additional Notes

1. Sincerity.The Japanese were not unaware that their failure to be specific in certain details would leave them open to a charge of insincerity. But they were faced with what amounts to a physical impossibility in communicating further details and for these reasons: (1) domestic pressure and the excitations caused by premature airing of the negotiations, and (2) international leakage. Whatever our Embassy may think about the inviolability of its own code, the Japanese are entirely convinced that every message going out from any source, either by radio or cable, is immediately seized, decoded and thoroughly understood by the agents of all the other Powers that are in any way interested. This is the reason they feel that they cannot themselves transmit a message through their own Foreign Office, or entrust a message to our Embassy for transmission, unless they are prepared to have it known by the agents of every other interested Government in the world.

An assassin’s bullet missed Prince Konoe by eighteen inches during the first week of October. The pressure on these men and the general difficulty of their position are important factors in accounting for their hesitation in discussing certain specific details.

With the exception of the obstruction caused by Mr. Matsuoka, the hesitations and mistakes of the Foreign Office are not indications of insincerity, but illustrations of the ingrained bureaucracy that characterizes all the departments of the Japanese Government without exception. One of the mysteries of Japan is the amazing independence of its separate departments, coupled with the equally amazing solidarity of them all in carrying out any well-established national policy. I think the true explanation is not insincerity but human nature. Each department is jealous of its own prerogatives, wants to do everything its own way, wants to have all the credit for anything that is done. Thus until a policy has become nationally established, the departments very largely go their own gait after the manner of departments everywhere.

The Japanese Cabinet admits that the move to Indochina was under pressure from the Army. The Army leaders feared that they were being let down in the negotiations and might be handed an uphill job after the negotiations had failed. They watched a lot of counter moves, thought they ought to make one themselves. Meanwhile, however, the Japanese Government has sent some picked army men to Indochina with instructions to put the brake on any extreme measures, and chief among the men with this mission is Colonel Iwakuro, who took part in the negotiations in Washington this summer and is still an ardent supporter of the peace plan. In addition, the Japanese Government insists that it has not violated a single item of the agreement reached with the French Government and, in fact, that it has not yet carried out many of the measures to which it is entitled under that agreement. In this connection a member of the Cabinet states that General [Admiral] Decoux has given false and exaggerated reports to certain American Consuls in Indochina with the obvious intent of instigating a war between America and Japan in the hope that such an eventuality might result in the return of the territory to France.

2. Ability.Japan is not a country of homogeneous political ideas. It is a politically young country, combining elements that lean toward the most advanced ideas on the one hand and to the most retroactive on the other, and including every shade of political theory between the two. There are solid elements strongly imbued with democratic and liberal ideals, and there are other elements, less entrenched, less numerous, but pushing and aggressive, who are deeply tinged with the most radical nationalism and totalitarianism. The Japanese are not like our people in subscribing only to a few tried and traditional political theories between which they oscillate slightly from time to time, but their minds are still open to all varieties of political thought, not excepting the wildest or most radical extreme, if it promises to benefit their country. They have no political philosophy. In this situation the actual policies of the Japanese Government are largely dictated by outside events which put one group or another in power for the moment according to the turn of the wheel. The present moment is the great chance for the liberals (Prince Konoe, the Peace Party, etc.). The German attack on Russia shook them all very seriously, radicals included. The radicals now hesitate and would welcome a safe way out of the Matsuoka situation, if it could be found. All realize that they must be in one camp or the other. The desire to get over into the democratic camp would be general if it could be thought possible without the loss of any essential national interest. However, if the Government fails to bring about this change and do it quickly, all together will abandon the attempt and yield themselves to the stream. If the liberal party that is pursuing peace, and is still held together by the most tenuous thread, should fail, it is certain that the Government will be given over to radical extremists of the worst type, and that all the national energy will then be harnessed for a wild and immediate plunge in the other direction.

Prince Konoe could not even have started the peace conversations without the approval of all the other strong elements in Japan, and this is the best indication that the Government that made peace would have their concurrence in case of success.

Prince Konoe was not a strong man in a weak position. He was a somewhat weak man in a very strong position. His character is mild and gentle and he lacks the aggressiveness to push people and things in any drastic degree. But after the Emperor he possesses the confidence of all elements in Japan, more than any other man. This is partly due to his position as leader of the Fujiwara family (royal blood), partly to his known disinterestedness and integrity, and partly to his success in coordinating and reconciling the forces of the nation.

The personal interest of the Emperor and his actual participation in detailed discussions regarding these peace negotiations are phenomena that have not occurred in the history of any similar negotiations during his lifetime.

3. Steps.The ability of any Japanese Government to carry out the terms of an agreement after it is made is such a basic question that it may be helpful to envisage the actual steps by which it would be done.

If a meeting should be brought about everybody in Japan will at once understand that the Prime Minister could only take part in it under the sanction of the Emperor, as indeed would be publicly announced. Once that is known, all the recalcitrant parties are put at an extreme disadvantage. When the Emperor gives an Imperial Rescript sanctioning any move or policy, it involves two things in the minds of all Japanese: (1) the knowledge that the Emperor would not do it at all unless his action had first secured the adherence of all the strong elements in the country, and (2) the actual sanction itself is taken to be the final seal that makes it the irrevocable policy of the nation. Any dissenters who revolt against such a fait accompli know that they have these two strikes on them in advance; (1) that they are officially and ipso facto traitors, and (2) that they will find all the strong elements of the Government and the country lined up solidly against them. In this situation rash acts on the part of a few firebrands, assassinations and so forth are possible, but no concerted rebellion on the part of recalcitrant elements, in the army or anywhere else, would be at all likely to succeed.

The same is a fortiori true of the implementation of any agreement that would result from the meeting. It would be given to the people sanctioned by the Imperial Rescript of the Emperor, and as such it would be established and entrenched as the sacrosanct national policy before any counteraction was possible.

- Future.

Friendship is the key to everything in the Orient. It makes everything possible and without it nothing is possible. It is doubtful if the legalistic and logical approach could ever result in a good agreement with an oriental nation, and it is highly probable that such an agreement, even if made, would not be carried out. Oriental minds, Japanese and Chinese alike, want to feel that they possess friendship, that they are understood, that they are in some definite camp, that they have some standby upon which they can rely in working out their national life. While they instinctively need this bulwark of friendship, they also instinctively respond to it, and once it is established they can be got to do almost anything within reason through its persuasive magic. They can be got to do nothing by logic or legalism, for they understand neither. If America should shake hands with Japan, it would have established the relationship that would enable it, with a little insistence now and then but easily and without any great pressure, to suggest and instill and effectuate a policy of justice, fair dealing, and friendly cooperation that would establish and perpetuate the peaceful development of the Pacific region while safeguarding the rights of all.

There would seem to be every hope that this action at the present time would establish a definite trend in the crystallizing Far East, and that the democratic and liberal ideas thus set in motion would, gradually indeed but nevertheless readily and naturally, become the settled direction and fixed policy of the entire region.

It is my own belief that the cooperation of the Chinese with the Japanese would follow almost automatically. It is perhaps worthwhile to recall that the Chinese were well on the way to actual collaboration with Japan when the Manchurian Incident rudely arrested the movement and turned the Chinese radically in the other direction. Another thing to be remembered is the well-known Chinese trait of pitting one power against another and always managing to hide behind somebody else. The Chinese are the most practically minded people on earth, and when they find that they can no longer divide and rule, they promptly set about the task of working out some form of satisfactory collaboration.

Seven months before he died Pope Pius XI discussed with me the situation in the Orient. At that time (May 1937 [1938]) the China conflict was less than a year old. He expressed the conviction that the Chinese and Japanese races complemented each other in their natural characteristics, that they had need of each other, that their geographic proximity rendered it absolutely necessary for them to live on friendly terms with each other, and that one of the greatest tasks awaiting statesmanship in the entire world was the reconciliation of these two nations on a basis of amicable cooperation.

Another basic factor in the whole problem is the internal reform of Japan itself that would be brought closer by establishing that nation in a policy of democracy, liberalism, and human rights. For good or ill, the aggressive energy of that pushing race will make trouble or effect good in the entire Pacific region according as it is directed in the right or the wrong channels.

We think it is always better to convert than to crush.

5. Terms.When I left Japan it was the feeling of Prince Konoe and his associates that the actual terms of the agreement were not the crux of the matter, but that the real question now at issue was rather the willingness of the American Government to make any sort of an agreement with Japan at all. The Japanese seemed to believe that all the essential terms to an agreement had been satisfactorily dealt with by them, with the possible exception of one or two small details that seemed to them not sufficiently important to prejudice the entire agreement. However, because there may still be some lack of clarification in regard to the terms and because the officials of the Japanese Government discussed their attitude toward them many times with me, I shall here cite a few points in regard to them that may prove helpful.

All the officials of the Japanese Government regret the September 4 confusion (except possibly the Foreign Office, one of whose men caused it). The September 4 document is now null and void and is to be considered as having no practical effect whatsoever.

Regarding the four specific points that were still under discussion at the last exchange of memoranda (territorial integrity of China, evacuation of China, freedom of trade, Article 3 of the Axis Treaty, if my memory serves me correctly), the Japanese Government now hopes that its formulae on these four points are satisfactory, and in any case it believes that it has already specified its attitude with all the precision possible by cable, and it would like to leave further precision for the actual meeting.

The Japanese represent that they make no claim to any portion of Chinese territory, and that they stand prepared to guarantee freedom of trade in the southwest Pacific, in the whole Pacific region, or in any particular area of it that may be defined.

The Prime Minister of Japan is prepared on the occasion of a meeting to anticipate all the various hypothetical cases that might possibly arise in the field of international relations, and he will state exactly what Japan will do in any and all of these possible cases, and he will give specific agreements to that effect which will provide for any and every contingency, and all of them will league Japan on the side of America in any conflict with any Axis power, provided only that America maintains at least a legal fiction of non-aggression. (This problem of stating explicitly the attitude of Japan in case Germany does this, Italy does that, or Russia does the other, is a matter that illustrates very well the difficulty of transmitting all pertinent details by cable.)

Regarding North China, the formula preferred by the Japanese is:

Cooperation against subversive elements until peace and order have been restored, this eventuality to be adjudicated and determined by China and Japan in conjunction.

Also the Japanese understand that the stationing of troops or police forces during this temporary period should be brought about by a mutual agreement between China and Japan.

Since territorial encroachment is entirely ruled out by the agreement itself, the Japanese do not see why they cannot be trusted to the extent of this temporary measure which is dictated by a very practical necessity.

The Japanese now have upwards of 200,000 civilians in that area engaged in trade, and in addition they project some economic development for the region. Unless all these civilians are to be taken out bag and baggage and the economic development completely abandoned, it would seem necessary (at least to me, and I believe to anybody who ever lived in China) to envisage or create some agency charged with peace preservation in the region until order has been established.

Understanding that this item was holding up the negotiations, I tried very hard to get the Japanese to agree unofficially to something short of actual occupation by their troops for an indefinite period. I proposed a time limit, but they demurred. I proposed a Chinese corps directed by Japanese officers, but they again demurred. I proposed the creation of an international police force, but I was informed that they had already anticipated this suggestion and ruled it out as impractical. However, I wish to remark in this connection that I believe their minds are not completely and irrevocably closed on this point. I believe their unwillingness to place a time limit on the occupation of the North China area, or to accept a suggestion that would replace the Army by some other body, is dictated not by insincerity or a determination to remain and encroach, but rather by a desire to save the face of the Army. Because I think this is the real reason back of their reluctance, I also think it might be possible to insist on one or the other of the first two suggestions, namely, a time limit or a Japanese-directed Chinese corps, when it comes to a final test. In short, I believe they would not abandon an otherwise advantageous and greatly desired agreement solely for this reason. They would certainly be very much embarrassed by such an insistence, but I think they would find a way out of it and would manage to reconcile their Army people, if they were pushed to it.

If this is true, it would mean that the evacuation question does not now involve the giving up of any undercover policy of territorial encroachment in North China or any other similar objective. Not that I fail to realize that such a policy would be nothing new. But I conceive that all their policies are now in flux, this long-cherished one among them.

I hope my suggestion will not prove misleading. And because it might do so, I will record the indications, slight and inconclusive in themselves, on which it is based. These indications are chiefly two, namely: (1) The fact that my Japanese consultants spontaneously came back to the question so often, lingered over it so long, played around with it in so many ways, seemed so reluctant to dismiss it and (2) the fact that once, when I had pressed them very hard on the reasonableness and feasibility of a time limit, the most trustworthy of the lot finally confessed to me that the one insuperable obstacle to any such formula was the need to save the Army’s face.

I doubt if they would agree to any formula of this sort prior to a meeting, because they would feel they could not afford to have it known ante factum by the Army, which catches and decodes every dispatch that goes out, including those of our own Embassy. I think they would agree to such a formula at a meeting, if pressed to it, because it could then be presented to the Army as a fait accompli.

My own guess at a formula that would meet with their reluctant acceptance and would at the same time work in practice if adopted, would be a time limit on the Army occupation (say six months or a year) followed by a Japanese-officered Chinese corps for an indefinite period.

This whole suggestion, however, represents nothing but my personal opinion founded on the slight grounds here described.

6. Alternatives.The Japanese appreciate the natural reason behind the attitude of insisting on knowing with certainty in advance that the meeting will prove a success, but they feel that this normally wise precaution should be waived in view of two unique factors in the present situation, namely: (1) their own physical inability to convey any more precision on specific details by any process short of a meeting, and (2) their feeling that the great amount of blind trust they repose in America by leaving the Axis camp should merit for them a slight return of similar confidence, and that it should take the form of trusting them to be sincere and reasonable in adjusting the few remaining details when the meeting takes place.

Here it may be apropos to recognize the fact that there is little to choose between the failure of a meeting and the failure of the negotiations. One is as bad as the other, for the failure of either will have the same unfortunate effect on international relations. That effect, according to the openly expressed views of all my Japanese informants, would be war.

Would war prove the corrective to usher in an era of better days for the people of the Pacific? It is difficult to think so. Present misery and future enmity would be the certain fruits of war with an oriental nation, whereas any good effects that might be envisaged are very problematical. Such a measure could hardly leave a likely soil in which to sow the seeds of amicable relations and peaceful development in the Orient.

Meanwhile China is war-weary. Its misery is mounting to the skies. Its dead through war, banditry, destitution and disease, according to an estimate made for me last week by the Bishop of Hong Kong, will be numbered in the tens of millions when it becomes possible to count the toll. Its good people must be ready to welcome an honorable peace that gives them back their country. I do not know if the same holds true of its leaders, but I would distinguish carefully between the sensibilities of the leaders and the real welfare of the people. I would also abstract from the revenge motive completely. It is natural that the leaders of China and their afflicted people should feel deep resentment against the atrocious conduct of the Japanese Army, but resentment is not the right foundation on which to build for the future. It seems best to leave the punishment of these wrongs to God, Who alone knows how to mete it out with medicinal justice. In the meantime, it is doubtless the proper business of men to erect on the firmest foundations available the structure of a practical and enduring peace.

There is no real peace anywhere in the Far East today. There is fear, tension, unrest and insecurity, where there is not actual strife. It would be a glorious thing if peace should come to the nations of the Pacific, with a workable freedom for each and a reasonable security for all, through the instrumentality of America.

J. E. WALSH

Superior of Maryknoll

October 18, 1941.

N.B.In presuming to file this memorandum for the possible consideration of the authorities of our Government I set out primarily to give an exposition and explanation of the views, attitudes, and statements of these Japanese officials and confidential agents with whom I have recently been in contact.

I spent two months (August 15 to October 13) in and around Tokyo, meeting these men almost daily and endeavoring to encourage them in their efforts to smooth the path to peace. I obtained a certain grasp of their opinion, and have tried to reflect this in my notes.

However, it was inevitable that I should form some opinions of my own, and I realize that many of them are inextricably woven into this narrative. I trust this will not be regarded as an impertinence. I should particularly regret any observation of mine that might appear to be phrased with a dogmatic ring, and if such be found, I ask that it be attributed to the haste in which I compiled these notes while travelling.

Prince Konoe the then Prime Minister. General Mutō Chief Central Bureau Military Affairs. Paul Ikawa Cooperative Bank. Dr. Nobumi Itō Member recent Cabinet. Mr. Kinkazu Saionji Personal Secretary Prince Konoe (Grandson of Prince Saionji, the late Genro). Mr. Ushiba Private Secretary Prince Konoe. Mr. Matsumoto Head of Dōmei News Service (personal adviser to Prince Konoe).

The Pittsburgh Press (October 18, 1941)

New ‘peace’ move –

Resume talks, Japs ask U.S.

New Premier backs request; America skeptical

By H. O. Thompson, United Press staff writer

Washington, Oct. 18 –

The Japanese government had communicated to the United States a desire to continue “peace talks” despite Japan’s political upheaval, it was learned today.

The Japanese acted to ease tension in the Pacific after world reaction had coupled collapse of the Konoe cabinet with possibility of a new thrust by Japanese armed forces. The overtures were received with some skepticism but makeup of the new Tokyo government led observers here to a more optimistic view.

Officials declined comment on the new Japanese cabinet headed by Lt. Gen. Hideki Tōjō pending clarification of its policies. This country has not closed the door to continuation of the “peace talks” but it is realized that they would have no chance of success should the new Tokyo government prove to be highly nationalistic.

Jap confers with Hull

Japan’s desire to keep the conversations open was conveyed to Secretary of State Cordell Hull last night by Kaname Wakasugi, minister-counselor of the Japanese embassy here. Wakasugi conferred with Under Secretary Sumner Welles for an hour and a half, then paid an unscheduled call on Mr. Hull.

The new overtures came from interim officials in Tokyo pending assumption of power by the new cabinet. They were advanced with the full knowledge of Premier Tōjō.

The rapid-fire developments in Tokyo preceding formation of the new cabinet had brought Congressional denunciation of Japan and an order for a few American vessels, presumably in Asiatic waters, to proceed to friendly ports at once “for instructions regarding their voyages.”

Fear German intrigue

It was conceded that the “peace talks” would collapse immediately should evidence develop of collaboration between Japan and Germany to jockey the United States into simultaneous crisis in the Pacific and the Atlantic.

There was some thought, expressed by House Democratic Leader John W. McCormack (Mass.), that the torpedoing of the USS Kearny yesterday might be a German effort to make Japan’s extremists think that events in the Atlantic might provide an opportune time for Japan to strike out in the Western Pacific.

U.S. gives ‘peace’ formula

Differences between the U.S. and Japan on Far Eastern issues have been narrowed somewhat recently but there still remained what one diplomat has described as “mountainous” obstacles.

The United States had informed Japan that this government is ready is negotiate a Far Eastern settlement under the following formula:

-

Japan must exercise national and international self-restraint and must refrain from the use of force in her international dealings.

-

The U.S. is ready to accept Japan’s contention that changes requiring new approaches to diplomatic problems have occurred but it is not willing to negotiate on the basis of changes which Japan has wrought by force of arms.

-

The U.S. insists upon effective equality of commercial opportunity.

-

The U.S. upholds the sanctity of treaties but agrees that treaties may be modified or altered, such changes, however, must be accomplished through orderly processes and not by force.

Japan has accepted the broad principles laid down by the American negotiators but has counters with the assertion that those principles can be attained in the Far East only by a full recognition and practical consideration of the actual circumstances of that region.

Japan has accompanied that rejoinder with a proposal for economic collaboration in the Far East between the U.S. and Japan. The U.S., after examining that proposal, found it unsatisfactory and rejected it in a communication to the Japanese government three weeks ago.

British await Jap showdown

U.S. may enter war, some in London believe

By William R. Downs, United Press staff writer

London, Oct. 18 –

Political and diplomatic quarters predicted today that the next few days would tell whether the new Japanese government intends to challenge the United States and Britain and informed sources cautiously added that the next few days might even bring the immediate entry of the United States into the war.

Some quarters expressed the hope that Japan would make a definite move to help her Axis partners, so Britain and possibly the United States could have a showdown in the Pacific.

It was pointed out that the establishment of security against aggression in the Far East would release troops and ships for action in Europe.

Cite Churchill’s pledge

Informed sources said the U.S. and Britain were working together closely in the Pacific. They pointed out that Prime Minister Winston Churchill had said on Aug. 24 that in the event of a breakdown of Japanese-American negotiations:

We, of course, range ourselves unhesitatingly on the side of the United States.

Informed sources weighed the factors they said would decide the new Japanese government for war or peace in the Pacific.

Factors which would tend to deter Japan from action were, they said:

-

She still has China on her hands.

-

Her stocks of war supplies are limited, and the possibilities of getting more precarious.

-

The Japanese Navy night be forced to fight the American, British, Russian, and Dutch fleets in the Pacific.

-

Japan is exceedingly vulnerable to air attack.

-

Japan is isolated from her Axis partners.

Factors ‘for war’

These factors might decide Japan for war:

-

Russia’s precarious situation in the west.

-

Japan’s urgent need for effective action against the American-British-Chinese-Dutch economic front.

-

The necessity of the United States delivering munitions, food and other war supplies through the Pacific to Russia, virtually placing these much needed commodities under the very guns of the Japanese fleet.

-

German pressure.

The Japanese crisis took precedence on the front pages of newspapers, and it was generally connected with the torpedoing of the U.S. destroyer Kearny.

The Daily Mail said:

Japan’s aggression is America’s business.

The News Chronicle commented:

Let it be said at once, if the Japanese move were not at once countered by an American declaration of war, Germany must stand enormously to gain.

U.S. Department of State (October 19, 1941)

751G.94/388: TelegramThe Consul at Hanoi to the Secretary of State

Hanoi, October 18, 1941 — noon. [Received October 19 — 8 a.m.]

160.A special Japanese economic mission, headed by Yokoyama and including about 80 members but having no connection with the Yoshizawa mission, arrived at Haiphong today. This mission will investigate the economic possibilities of Indochina and prepare for Indochinese-Japanese “collaboration” in these possibilities. My informant stated that the Japanese have indicated that the mission will be interested primarily in rubber and minerals and that the establishment of cotton piece goods factories and the development of the salt industry will be of next importance. He added that a further group of approximately 80 will arrive to join the mission. He felt that this mission is but one more step in the Japanese intention to control Indochina’s economy.

Sent to Cavite for repetition to the Department, Chungking, Peiping, Hong Kong, Shanghai. Shanghai please repeat to Tokyo.

REED

894.00/1118: TelegramThe Ambassador in Japan to the Secretary of State

Tokyo, October 19, 1941 — 3 p.m. [Received October 19 — 10:09 a.m.]

1656.Shortly after its investiture last night the new Government issued a declaration translated as follows:

It is the immovable policy of Japan to settle successfully the China affair and to contribute to the peace of the world by establishing the East Asia co-prospering sphere. The Government which faces an unprecedentally grave situation intends externally to promote more and more amicable relations with friendly powers and is absolutely [determined?] to perfect a national defense state; and thus under the august virtue of His Majesty the Emperor to go forward with a united nation to accomplish its holy task.

In a brief radio address to the nation, the new Premier reaffirmed the basic policies stated above. Demonstrative omission of reference to the Tripartite Alliance is significant.

The new Foreign Minister, Shigenori Tōgō, refused to make a statement to the press except to express support of the basic policies of the Government. He will not comment on relations with the United States but indirectly referred to recent criticisms of “secret diplomacy” by stating that he would:

…let the people know regarding the diplomacy of the country as much as possible on as many occasions as possible.

Other members of the new Government made the usual platitudinous remarks but no concrete announcements of policy were forthcoming.

GREW

U.S. Department of State (October 20, 1941)

711.94/2382: TelegramThe Ambassador in Japan to the Secretary of State

Tokyo, October 20, 1941 — 5 p.m. [Received October 20 — 12:35 p.m.]

1661.As the political background against which the recent change of Cabinet took place has been fully presented in a number of my confidential telegrams of the past 6 weeks or more, I shall withhold definitive assessment of the new Cabinet and of its policies until some tangible material becomes available. As, however, American radio broadcasts and reports of American press comment indicate that the Cabinet change is almost universally interpreted by the American public as an adjustment preliminary to an attack by Japan on Russia or to some other drastic action which must inevitably lead to war between the United States and Japan, I submit certain considerations, some of which rest on fact and some on reasonable assumption, that suggest that the view which seems to have been taken by the public at home with regard to the significance of the Cabinet change may not be in accurate perspective.

According to an informant who is close to Prince Konoe, the latter chose to retire and in retiring insured that his successor should be one who would endeavor to follow the course laid down by the previous Cabinet toward adjusting relations with the United States and settlement of the China conflict. A valid reason for believing that General Tōjō answers this description is that he is one of the five members of the Konoe Cabinet who initiated and directed the informal approach to the American Government out of which there developed the current exploratory conversations.

We anticipated that if either the preliminary conversations or the contemplated formal negotiations should fail, Prince Konoe would be obliged to resign to be replaced not by a civilian but by a military dictatorship. As the conversations have not been terminated, the conditions to which that forecast was applicable did not arise. We suggest as a likely reason for Prince Konoe’s resignation his belief that the conversations would proceed more rapidly if the American Government were to deal with a Prime Minister whose influence rests on leadership in and on support of the Japanese Army, which has the final voice in matters of policy, rather than with an intermediary. Although as anticipated Prince Konoe was followed by an army leader and not by a civilian, intimations of readiness by the new Cabinet to continue the conversations, together with the circumstances set forth in the preceding paragraph, would indicate that it would be premature to characterize the new Cabinet as a military dictatorship committed to the pursuit of courses calculated to lead to war with the United States.

An important aspect of General Tōjō’s appointment lies in the fact that, unlike previous military Prime Ministers in Japan, he is not retiring from the Army but is maintaining his position as a full general in the Army. For the first time in recent history, the Army itself is thus accepting responsibility for the conduct of government and governmental policy, a responsibility which hitherto it has refused to assume. It may also be logically expected that General Tōjō’s retention of his position in the Army will afford him a greater degree of control over extremist elements within the Army than would otherwise be the case.

The appointment of Mr. Tani, formerly Vice Minister for Foreign Affairs, as President of the Cabinet Information Board, is a favorable indication. He is known to me as a levelheaded, forward looking, and friendly Japanese. In private and confidential conversations with me he has on several occasions condemned the Tripartite Alliance in unqualified terms.

A member of my staff who became acquainted in Moscow with the Foreign Minister, Mr. Togo, and who has met the latter’s wife and daughter several times after their return to Japan, informs me that Mr. Togo, as Ambassador at Moscow, was highly regarded by the Soviet Government as the most acceptable Japanese representative in recent years. According to reliable reports, the Soviet Government was openly disappointed over Mr. Togo’s removal in October 1940, in view of the conversations looking toward the conclusion of a political treaty which he had been conducting up to that time with success. On the occasion of Mr. Togo’s departure for [from?] Moscow he was tendered unusual courtesies by the Soviet Government. It will also be recalled that Mr. Togo was included in the “purge” carried out by Mr. Matsuoka last year, reportedly on the grounds that he was too moderate in his views and opposed to the extreme foreign policies carried forward by Mr. Matsuoka.

According to a statement just released by Dōmei, the official Japanese news agency, the new Cabinet will formulate no new policies for the reason that the basic national policy had already been laid down by the Konoe Cabinet.

GREW

The Pittsburgh Press (October 20, 1941)

U.S.-Jap talks will resume

But Tokyo prepares for ‘any eventuality’

By Robert Bellaire, United Press staff writer

Tokyo, Oct. 20 –

Authorized informants said today that the government would resume negotiations with the United States, probably within a week, to determine whether better relations are possible but would prepare the country economically and militarily for any eventuality.

The new government’s plan was disclosed as two Japanese liners sailed to repatriate Japanese citizens in the U.S. and to take with them to the U.S. American citizens long resident in Japan, and as General Hideki Tōjō, the new premier, said in a speech to officers stationed at the War Office:

Japan is now at the point where it must rise or fall and therefore the entire Japanese nation must be strongly consolidated.

Warn his army officers

General Tōjō, speaking in his joint capacity of Premier and War Minister, said it was absolutely necessary to consolidate the nation’s total power and to push its policy resolutely to:

…eradicate causes of Chinese-Japanese hostilities and place Japan in perfect security for 10,000 years against the encircling front of hostile nations against Japan.

He warned that army officers and men must be circumspect in their conduct and strongly united.

Then General Tōjō, who is also Home Minister, went to the Home Ministry, where after giving instructions to officials, he said to newspaper correspondents:

Our policies have been decided at a cabinet meeting. Therefore we have only to follow them and enforce them.

I dislike talking and therefore I will make my policies clear by enforcing them. This applies to elections, the preservation of peace and administrative reform. Because I am Premier, I cannot be careless in my remarks.

Urges army, navy cooperation

Meanwhile, Foreign Minister Tōgō said in a national broadcast today that Japan’s diplomacy must stem from a greater unity of foreign and military policies which will insure the defense of Japanese honor “at all costs.”

Tōgō said:

The ultimate goal of Japanese diplomacy, needless to say, lies in maintaining and promoting world peace but as far as the existence of our empire and honor are concerned, we are grimly determined we must defend our country to the death and strive to achieve our historical mission.

Previously the new Navy Minister, Admiral Shigetarō Shimada, said in a radio speech that the navy was prepared to meet any change in the situation which confronted Japan, and that so long as the army and navy cooperated closely, and the government and the people were willing to surmount all difficulties, Japan would be in a position of perfect security.

The army and navy do not always cooperate closely. The navy is traditionally more conservative and especially has opposed, to date, any move that might involve Japan in war with the United States.

One Japanese liner has already sailed for the U.S. with Americans, under instructions to embark Japanese now in the U.S.

Today the 14,457-ton liner Taivo Maru sailed from Kobe for Honolulu and the 11,622-ton Hikawa Maru sailed for Seattle, where it is due Nov. 2.

The Taivo Maru carried 150 American citizens of Japanese descent, who are to go to Hawaii, two native Americans, F. W. Bender, manager of the recently-closed Kobe branch of the National City Bank of New York, and his wife. The Taivo Maru is to call at Yokohama Wednesday to embark more passengers, mostly American citizens of Japanese descent.

The passenger complement of the Hikawa Maru was not disclosed.

The Stock Market, opening for the first time since last Thursday, opened stably today. A succession of routine holidays had kept it closed during the Cabinet crisis which resulted in the resignation of Prince Fumimaro Konoe and his succession by General Tōjō.

Foreign diplomatic quarters regarded the succession of the Tōjō Cabinet as a victory for the Axis. But at the same time they said it was a surprisingly moderate one for an army-led government and therefore they did not look for any immediate crisis during negotiations at Washington.

Blame internal affairs

They said this was especially true because General Tōjō was reported to share the desire of the previous government for better relations with the United States.

The newspaper Miyako said today that these four concessions by the United States can avert a Japanese-American conflict.

-

That the United States follow a policy in the Far East independent of that of Britain and judge conditions “realistically.”

-

A cessation of assistance to the nationalist government of China in Chungking while Japan “adjusts” her relations with Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek.

-

Washington to cease leadership in the effort to form a group of nations encircling Japan including China, Britain and the Dutch East Indies.

-

A general Japanese-American agreement to preserve and enforce peace in the Pacific Ocean area.

Aid to Russia cited

The Japan Times and Advertiser, which frequently reflects the viewpoint of the Foreign Office, urged that the United States become friendly with Japan in the event that it intended to aid Russia effectively.

It said:

When relations between Japan and the United States are as strained as at present, American aid to Russia, if carried beyond a certain point, is almost certain to aggravate the Pacific situation.

General Tōjō effected a large-scale reshuffle of prefectural governors and named a new man, Yūko Tomioka, to be superintendent of the metropolitan police board, one of the most important domestic offices in the country.

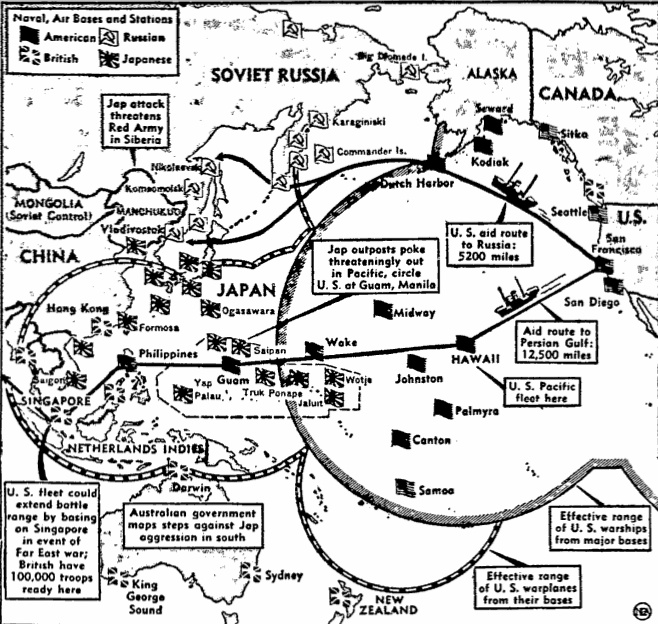

The Pacific picture as ‘war cabinet’ rules Japan

The map shows the lineup of the powers in the Pacific as Japan’s new “war cabinet” prepared to resume negotiations with the United States but prepared economically and militarily for “any eventuality.”

Dutch East Indies ready to fight Jap aggression

By Edgar Ansel Mowrer

Batavia, Oct. 20 –

The Dutch East Indies are ready to play an energetic part in opposing any new Japanese aggression that will be opposed by the United States, according to trustworthy information.

From personal contact, I can say that Vice Admiral Helfrich, commander of the Dutch naval forces, and Gen. H. Terpoorten, acting army commander, are both confident that the Netherlands East Indies will prove to be a powerful stronghold in the American-British-Chinese-Dutch front, a front which they believe is strong enough to checkmate Japanese designs.

Both of those offensive-minded officers stress their intention of defending the Dutch Indies under any and all circumstances.

According to belief here, the Japanese armed forces in Indochina number two divisions, or something over 30,000 men, supplemented by 50,000 more, together with transport ships ready at Hainan Island.

Chinese sources insist that the Japanese, along the Indochina railway from Laukkai to Hanoi, are building shelters for several more divisions.

Tōjō-Tōgō spells Axis

Danger of war in the Pacific is not lessened by the decision of the new military government of Japan to continue conversations with the United States. Premier General Tōjō is a warrior, picked as such.

He is not only a leader of the militarist faction, but definitely pro-Axis. And he is the closest to a dictator that the Japanese system of emperor-dictation permits, because he heads the war and home ministries in addition to holding the premiership.

Since General Tōjō was “overwhelmed with a mingled feeling of austerity and joy” when Japan joined the Axis as an avowed move against the United States, he naturally chooses a pro-Nazi, anti-Russian Shigenori Tōgō as Foreign Minister. The latter is a former ambassador to Berlin and has a German wife.

If Japan refrains from another war move, it will not be for lack of a military dictatorship and mobilization. She is as ready for war as she ever will be – better prepared, indeed, because the American-Anglo-Dutch embargo on war supplies is cutting her essential reserves for the future.

Tōjō’s watchful waiting, like that of his predecessor, is due to the fact that Hitler is six weeks behind schedule in knocking out Russia. Unless all signs fail, the fate of the Red Army rather than the stalling conversations with the United States, wuill determine Japan’s next move.

U.S. Department of State (October 21, 1941)

894.00/1120: TelegramThe Counselor of Embassy in China to the Secretary of State

Beiping, October 20, 1941 — noon. [Received October 21 — 7:17 p.m.]

313.An American press representative here informs me that a Chinese source with good Japanese connections states that the Japanese Navy greatly fears the combined American and British fleets and would be very reluctant to approve a Premier whose policy meant war or serious chances of war with the United States; therefore, the present Premier, while having great power in Japan because concurrently heading Home and War Ministries, will be wary of any situation involving war with the United States, and Japanese press bluster is largely for home and Axis consumption. This source considered American action in recalling American vessels from Japan and China waters and other action indicating that the United States will use force would have a sobering influence on Japanese officialdom which still is not fully convinced that the United States and Great Britain will fight Japan.

I am informed by another source usually reliable that the meeting of veteran Chinese statesmen and military leaders held in Peiping at the end of September on the invitation of the North China Political Affairs Commission was to have been the signal for launching an independent North China but at the last minute General Okamura, Japanese commanding officer in North China, received orders from the Army Chief of Staff, General Sugiyama, to call it off and the meeting degenerated into a social affair. This source does not know the reason for the change.

Sent to the Department, repeated to Chungking and Shanghai.

BUTRICK

793.94/16985: TelegramThe Military Attaché in China to the War Department

[Extract]. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Chungking, October 21, 1941.The official Chinese view is that the Japanese will begin an offensive in Eastern Siberia within two weeks. It should be noted that several months before the beginning of the Russo-German war, the Chinese predicted the date it would start, and missed it by only a few days.

In Indochina, the Japanese are laying in supplies for 100,000 troops, but the Chinese report of large additional troop movements into Indochina has not been confirmed. It is estimated that there are not more than 40,000 there at present.

MAYER

The Pittsburgh Press (October 21, 1941)

New cabinet confers –

Stronger Axis, Jap ties asked

By Robert Bellaire, United Press staff writer

Tokyo, Sept. 21 –

The members of the House of Representatives who comprise the “Throne-Assisting Diet Members’ League” asked the new government today to “strengthen the Axis alliance and eliminate challenging acts by third powers hostile to Japan,” patently the United States and Britain.

They presented a resolution to Premier Hideki Tōjō, assuring him and his cabinet of their support, and urging that a super-national defense state be attained so “the world mission of Imperial Japan” may be realized.

The cabinet held its first regular meeting today, and Foreign Minister Shigenori Tōgō explained repercussions of the new government’s formation in Britain, the U.S., Germany and Italy. It was announced that Minister-at-Large Haruhiko Nishi, who, having spent more than 10 years in Russia, is considered an expert on Russian affairs, had been appointed Vice Foreign Minister, succeeding Eiji Amau.

Meanwhile, Minister of Commerce and Industry Shinsuke Kishi reshuffled his ministry’s personnel on an unprecedented scale. At least 12 department chiefs were involved.

Newspapers began to temper their attacks on the U.S. and Great Britain, and Hōchi predicted that the German-Russian war would be a long one.

The removal of Russian officials from Moscow, the newspaper said, was apparently the first stage of a protracted war. It predicted that Russia would continue guerilla warfare, similar to that of the Chinese against Japan, but Hōchi doubted that the Russians could hold out as long as the Chinese.

The newspaper Asahi, commenting on a dispatch from its Washington correspondent, said the United States apparently wants to continue negotiations for “peace” with Japan. With the new cabinet’s installation, Japan’s preparations for war, if it must come, are completed, the newspaper said.

…but it is not yet too late… even if the last five minutes, Japan will be unstinting in its efforts to establish peace.

Must achieve mission

Other newspapers hailed Premier Tōjō’s instructions to the Army he had said it was absolutely necessary to consolidate the nation’s total power and push its policy resolutely – as most appropriate, considering that Japan was “at the crossroads.” Nichi Nichi said that the Tōjō Cabinet would go “all out” for successful conclusion of the China “affair,” defying any and all obstacles.

Chief government spokesman Koh Ishii, asked whether the negotiations with the United States were being continued, replied:

I can only day that they are not cut off.

As to whether Japan’s basis for the discussions had changed because of the new government, he said:

Please draw your own conclusions from the Foreign Minister’s radio speech last night.

Tōgō had said that:

…the ultimate goal of Japanese diplomacy… lies in maintaining and promoting world peace, but as far as the existence of our empire and honor are concerned, we are grimly determined we must defend our country to the death and strive to achieve our historical mission.

Chungking expects Japan to go easy

Chungking, Oct. 21 –

What is happening in Soviet Russia now dominates the entire Far Eastern situation in an unprecedented manner.

As never before, a western war threatens to merge with an eastern. If Moscow falls, the temptation to the Japanese militarists to strike at the Soviets in Siberia from Manchukuo will be great, and some officials here are frankly prepared to see that occur within two or three weeks.

Other officials here think that Japan’s new premier, General Hideki Tōjō, and his government will hesitate to take the plunge unless an irreparable disaster befalls the Russians along the Volga.

It is believed by those most familiar with the internal divisions in the Japanese Army that the decision will depend upon how successfully General Tōjō has replaced extremists among the higher officers with moderate commanders at key points, in recent months, especially the Manchukuo commands.

U.S. Department of State (October 22, 1941)

894.00/1121: TelegramThe Ambassador in Japan to the Secretary of State

Tokyo, October 22, 1941 — 6 p.m. [Received October 22 — 6:34 a.m.]

1673.The appointment of Haruhiko Nishi as Vice Minister for Foreign Affairs, whose last post was Counselor with rank of Minister in Moscow, was announced in the press this morning. Mr. Nishi has been occupied during recent years, both in the Japanese Embassy in Moscow and in the Foreign Office at Tokyo, with Soviet-Japanese relations. He has the reputation both here and in Moscow of being an honest and trustworthy man without, however, any outstanding ability or intellectual attainments.

With the appointment of Nishi, both the Minister and the Vice Minister for Foreign Affairs are professional Japanese diplomats who have had first-hand experience in the Soviet Union and are both regarded as at least not unfriendly toward the Soviet Government.

GREW