At Sixth Army Headquarters, Captain Behr kept the lines to Gerhard Stöck open throughout the day. Stöck had proved to be the most reliable witness to the unfolding chaos. He kept reporting the defection of Rumanian officers, who left thousands of soldiers to wander the steppe, and his account of the tragedy was distressingly accurate. On his own maps, Behr had also watched the slow progress of General Heim’s relief force. The 48th Panzer Corps finally reached Blinov in the afternoon. But the Russians had come and gone, hitting and running across the flatlands. General Heim took his panzers out of town again, seeking the elusive enemy, who was avoiding direct engagement.

In Stalingrad, ninety miles east of the fluid battleground, the city had again assumed its familiar crown of explosions and tracer bullets chasing each other through the darkening sky. On the edge of the Volga, Russian Col. Ivan Lyudnikov’s trapped division still clung to its “island” under the cliff behind the Barrikady Gun Factory. Up above, German pioneers had spent another day trying to destroy them, but again they failed. Inside the Barrikady itself, Maj. Eugen Rettenmaier learned of the Russian counterattack back at the Don and sank into a deep depression. Unable to understand how his leaders had failed to prepare for the blow, he knew the situation at Stalingrad had become hopeless.

North of the Barrikady, past the shattered tractor works, the 16th Panzer Division had spent another torturous day on the outskirts of Rynok. But after dark, they received orders to turn their backs on the Volga. Mechanics labored hurriedly over tanks and trucks; soldiers received extra rations and ammunition. Then they filed out of their deep balkas, where they had lived since August, and went to shore up the gap in the line along the Don, ninety miles to the rear.

The weather was turning worse; a strong wind blew snow into the faces of the tankers and infantrymen. Masses of people wandered past them: Rumanians clutching their belongings, human flotsam from an unseen debacle beyond the western horizon.

At Golubinka, General Schmidt read the latest dispatches and tried to gauge the extent of the Russian penetration. Scattered rumors merged with verified reports to form a kaleidoscope of tank sightings, making it impossible to pinpoint the enemy’s whereabouts. At 10:30 P.M., Schmidt suddenly announced: “I am going to bed now,” and disappeared into his quarters. As he went back to the phone and Gerhard Stöck, Captain Behr marveled again at Schmidt’s coolness, a blessing in the face of the long day’s discouragement.

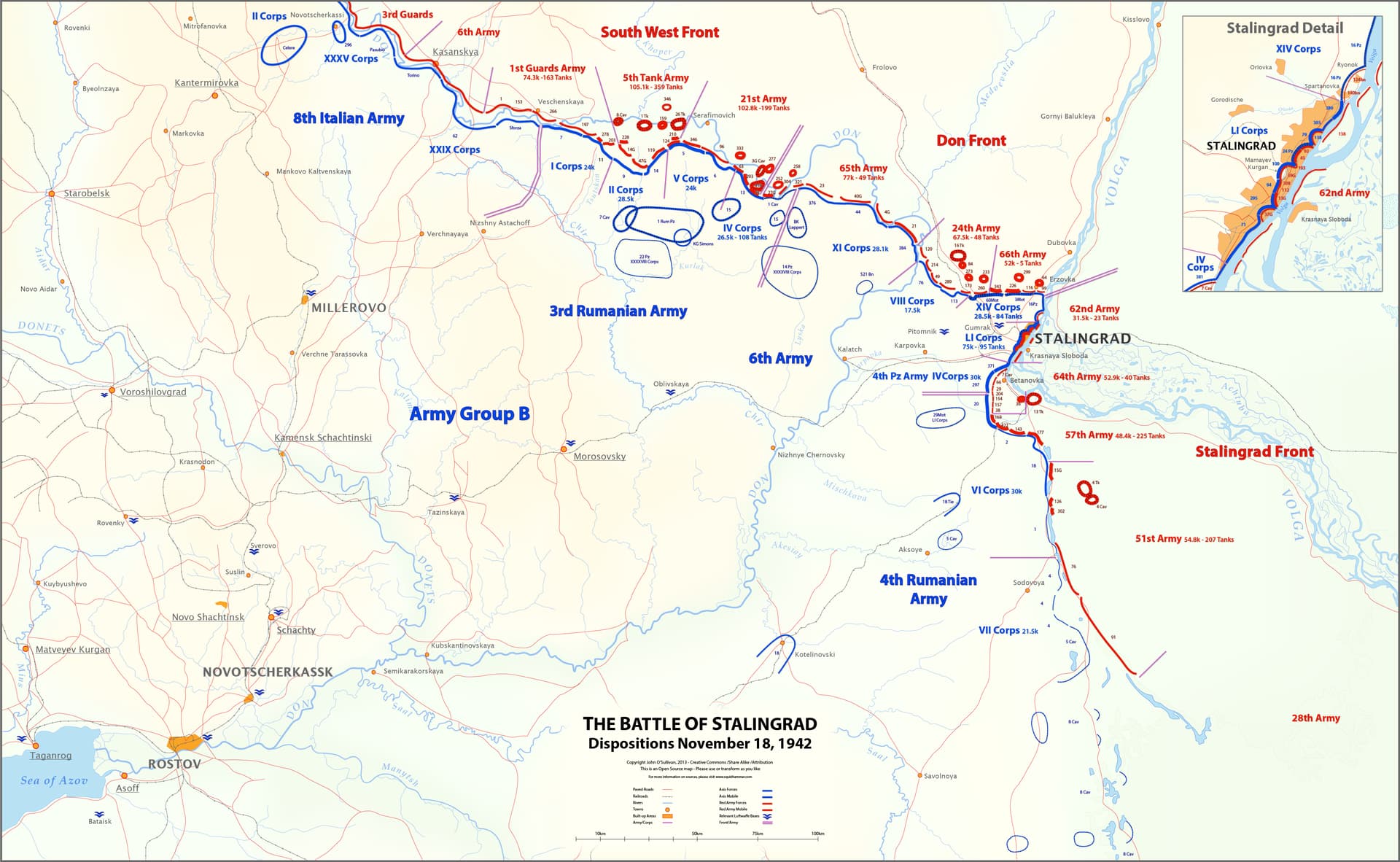

South of Stalingrad, more Russian forces waited through the bitterly cold night to begin the second part of Operation Uranus. From the suburb of Beketovka down to the shores of the salt lakes, Sarpa, Tzatza, and Barmantsak, the Sixty-fourth, Fifty-seventh, and Fifty-first armies were massed along a 125-mile front. Confronting them was the vastly overextended Fourth Rumanian Army, stretched thin across the wintry steppe to protect the German Sixth Army’s right flank. It was the Russian High Command’s intention to punch quickly through the Rumanian positions and race northwest toward the Russian armies descending from the Don.

In the early hours of November 20, shivering Red Army soldiers cleaned their weapons again, and wrote last letters to relatives in unoccupied Russia. Sgt. Alexei Petrov had no one to write; Lt. Hersch Gurewicz thought wistfully of his father and brother, but had no idea where they were.

At his headquarters cottage, General Yeremenko could not sleep. Convinced that the southern-front attack should be delayed until all the German reserves had been drawn north to meet the first phase of the Soviet offensive along the Don, he had spent hours arguing his case with STAVKA in Moscow. But STAVKA had refused his plea, and now Yeremenko brooded about the possibility of failure.

At dawn he had more worries. The weather had not changed, and a thick fog, mixed with snow, shrouded his armies. Troops had great difficulty forming into assault groups. Tanks ran into each other. Airplanes poised to the east, across the Volga, sat helplessly on runways.

Yeremenko delayed H-hour. From Moscow, STAVKA demanded the reason and Yeremenko sat at his desk and patiently explained his decision. STAVKA was not happy, but Yeremenko held his ground. For more than two hours, past nine o’clock, he waited for the weather to clear. As STAVKA came back on the BODO line to plague him, his meteorologists promised sunlight within minutes.

At 10:00 A.M., Yeremenko’s artillery commenced firing and the soldiers of the Rumanian Fourth Army fled wildly in every direction. Within a few hours, the astonished Yeremenko excitedly called STAVKA to say that ten thousand prisoners had already been processed. STAVKA demanded he recheck his figures. They were correct.

Pvt. Abraham Spitkovsky had seen the prisoners coming almost as soon as the bombardment ceased. Rising from his hole when the “Urrahs” from his comrades sounded the charge, he plunged through the snow toward hundreds of black figures walking toward him with hands raised over their heads. Up and down the front beside him, Russian soldiers shot blindly into the ragged ranks and when Spitkovsky thought of the weeks and months of running, of cringing among the corpses, and of lice he, too, brought up his machine pistol and fired long bursts into their columns. While Spitkovsky paused to reload his gun, he looked down at the rows of dead men and was completely unmoved.

One hundred twenty miles northwest of General Yeremenko’s almost effortless breakthrough, the Germans were still trying to contain the Russian forces moving down from Serafimovich and Klatskaya.

At the village of Peschanyy, thirty miles south of Serafimovich, General Heim’s 48th Panzer Corps finally met the enemy. His 22nd Panzer Division plunged into a firefight with T-34s, but the 22nd was already crippled; its mouse-eaten wiring had reduced tank strength to twenty.

Antitank guns acting as support helped explode twenty-six Russian tanks, but that was not enough. The Soviet armor broke away and the Germans hobbled after it. By the afternoon, the panzers were surrounded by new Russian formations and fighting for survival.

The steppe battleground resembled islands in a sea. Trapped units retreated into hedgehog defenses and lashed back at the enemy closing in around them. The Rumanians who continued to fight were almost totally isolated. A meteorological officer in the 6th Division kept a diary, later captured by the Russians:

"November 20 In morning enemy opened heavy artillery fire at sector held by 13th Pruth Division.… Division wiped out.… No communication with higher command.… Currently encircled by enemy troops. In pocket are the 5th, 6th and 15th divisions and remnants of the 13th Division. The report spoke for the entire “puppet army.”

During the night, German Quartermaster Karl Binder had crossed and recrossed the Don, bringing out food and clothing for his 305th Division. Back again on the western side of the frozen river, he found that his old supply depot at Bolshe Nabatoff still remained in German hands. The Russian tanks had merely burned some of the buildings before racing off again into the fog. Binder collected what equipment he could from the ruins, then returned to the bridge at Akimovski to wait for his cattle. Lost somewhere in the near blizzard of the previous night, the herd had not been seen by anyone.

On a bluff overlooking the town, Binder stared west into the vast steppe. Close by him, two Russian prisoners were being interrogated by a German officer, who suddenly shouted something and waved a pistol. When one of the Russians bolted, the German shot him in the back of the head.

Horrified, Binder rushed over and begged the officer to spare the other prisoner’s life. He said he could use him as a driver. The officer shrugged disdainfully and holstered his weapon. Binder led the Russian back to his car, where the prisoner poured out a torrent of thanks in fluent German. The young man explained that he had learned the language while studying medicine in Moscow.

Russian shelling increased; dead bodies lined the roads, and wounded men called for help. A Rumanian officer waved feebly from a clump of bushes, and Binder and his new friend went to him. The man had wounds in an arm and his right leg. After Binder cut open his trousers, the Russian medical student took his knife and skillfully picked pieces of shrapnel from the lacerations. The Rumanian fainted.

Binder heard his cattle coming long before they showed on the horizon. With shells bursting intermittently in the town of Akimovski, he stood patiently at the bridge and listened to the sound of hooves hitting the ground. Then they appeared, a mass of animals, raising a huge cloud of snow as they ran ahead of the shouting herdsmen. Their noses dripping icicles, their eyes caked with ice and snow, they passed over the bridge into corrals in the deep balkas between the Don and Volga. Satisfied with his coup, Binder dropped the Russian and wounded Rumanian officer at a dispensary and started setting up new depots for his division on the east side of the Don.

Only a few miles away, Gen. Arthur Schmidt was briefing Friedrich von Paulus at Sixth Army headquarters about the deteriorating situation. After announcing that the 24th Panzer Division was having difficulty negotiating immense snowdrifts on the way from Stalingrad to defend the vital bridge at Kalach, he added that a Russian tank column had just been reported within range of Golubinka itself.

Paulus abruptly terminated the discussion. “Well, Schmidt, I will no longer stay here. We will have to move.…”

Paulus suddenly seemed agitated and even Schmidt lost some of his calm. The two men said a curt good-bye to their staff and went out to pack.

They took off a short time later and flew first to Gumrak Airport, five miles west of Stalingrad. After a brief conversation there with General Seydlitz-Kurzbach, they flew southwest to the communications center of Chir, from where Paulus hoped to maintain reliable radio contact with higher headquarters.

In the meantime he acted quickly to smash the second stage of the Soviet counterattack by sending the 29th Motorized Division into battle south of Stalingrad. On alert to join General Heim’s 48th Panzer Corps west of the Don, the 29th was able to move swiftly through rolling fog on the right flank of the Russian Fifty-seventh Army, which was pushing past negligible resistance from Rumanian outposts. The counterattack stunned the Russians.

Both sides suffered losses as the first tanks opened fire, and, when mounted infantry clashed, the full battle was joined. The fog lifted and German observers saw a Soviet armored train passing by to the west. Behind it several other freight trains had stopped to disgorge Red Army foot soldiers. German panzers sighted on these inviting targets and poured hundreds of shells into the packed boxcars.

Through binoculars, the gunners watched countless Russian bodies cartwheeling into the air and down onto the snow. On either side of the railroad embankment, Soviet tanks milled about, ramming each other and firing aimlessly. German batteries shot point-blank into these vehicles and the Russian 13th Mechanized Corps, ninety tanks strong, began to blaze and explode. Sensing a chance to completely seal the Russian breakthrough on the southern flank, 29th Division commander, Gen. Ernst Leyser, prepared to annihilate the burning enemy force. But as he did so an order reached him from Army Group B, more than two hundred miles away at Starobelsk, to pull back and guard the Sixth Army’s rear at the Don. In the fading afternoon light of November 21, the frustrated Leyser reluctantly broke contact and rode off to the northwest. From nearby fields, tanks started to fire over his car at unseen targets. The general suddenly had no idea whether they were friends or foes.

General Leyser’s temporary victory brought a brief dividend to Paulus. News of the bloody defeat of the Russian 13th Corps quickly filtered back to Gen. Viktor Volsky’s 4th Tank Corps and Volsky (who was suffering tuberculosis at this stage) slowed his drive, now aiming for Kalach on the Don. Still spitting phlegm into his handkerchief, the cautious officer refused to go on and insisted on reinforcements against renewed German assaults. But the Germans had gone.

Agonizing over the rupture of both his flanks, General Paulus made up his mind about the future. He authorized a dispatch to Army Group B at Starobelsk and recommended the obvious: withdrawal of the Sixth Army from the Volga and Stalingrad to positions more than a hundred miles to the southwest, at the lower Don and Chir rivers.

Army Group B commander, Freiherr von Weichs, forwarded the recommendation to OKW headquarters in Rastenburg, East Prussia, with a strong endorsement. He shared Paulus’s conviction that an immediate withdrawal was the only alternative to total disaster.

And disaster was close at hand. South of Stalingrad, General Yeremenko’s units, after crushing the Rumanians, split “Papa” Hoth’s Fourth German Tank Army in two. At a weather-beaten farmhouse outside Businovka, “Papa” Hoth sat besieged. Outside, the wind howled at the windows which were boarded over and stuffed with bits of paper and cloth. Inside, flickering candles shone on a band of weary staff officers, trying to keep in touch with their scattered combat groups on the steppe.

Messengers arrived in a stream with pleas from trapped regiments. At a solitary telephone, an officer scribbled down final words from decimated formations as they fell under Russian armor. Hoth was helpless. With the Rumanian forces destroyed, he had too few guns and tanks to stop the enemy. It had also become apparent that the Soviet plan was breathtaking in scope. Colored arrows on the battle maps already showed a distinct arc to the northwest, around his pitiful forces, toward Kalach and its bridge over the Don. If the bridge should fall before Sixth Army pulled back from the Volga, Hoth foresaw a mass grave for the Germans in Stalingrad.