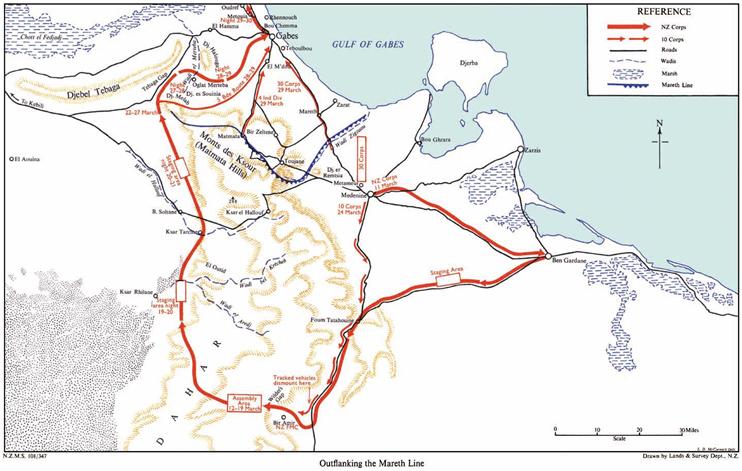

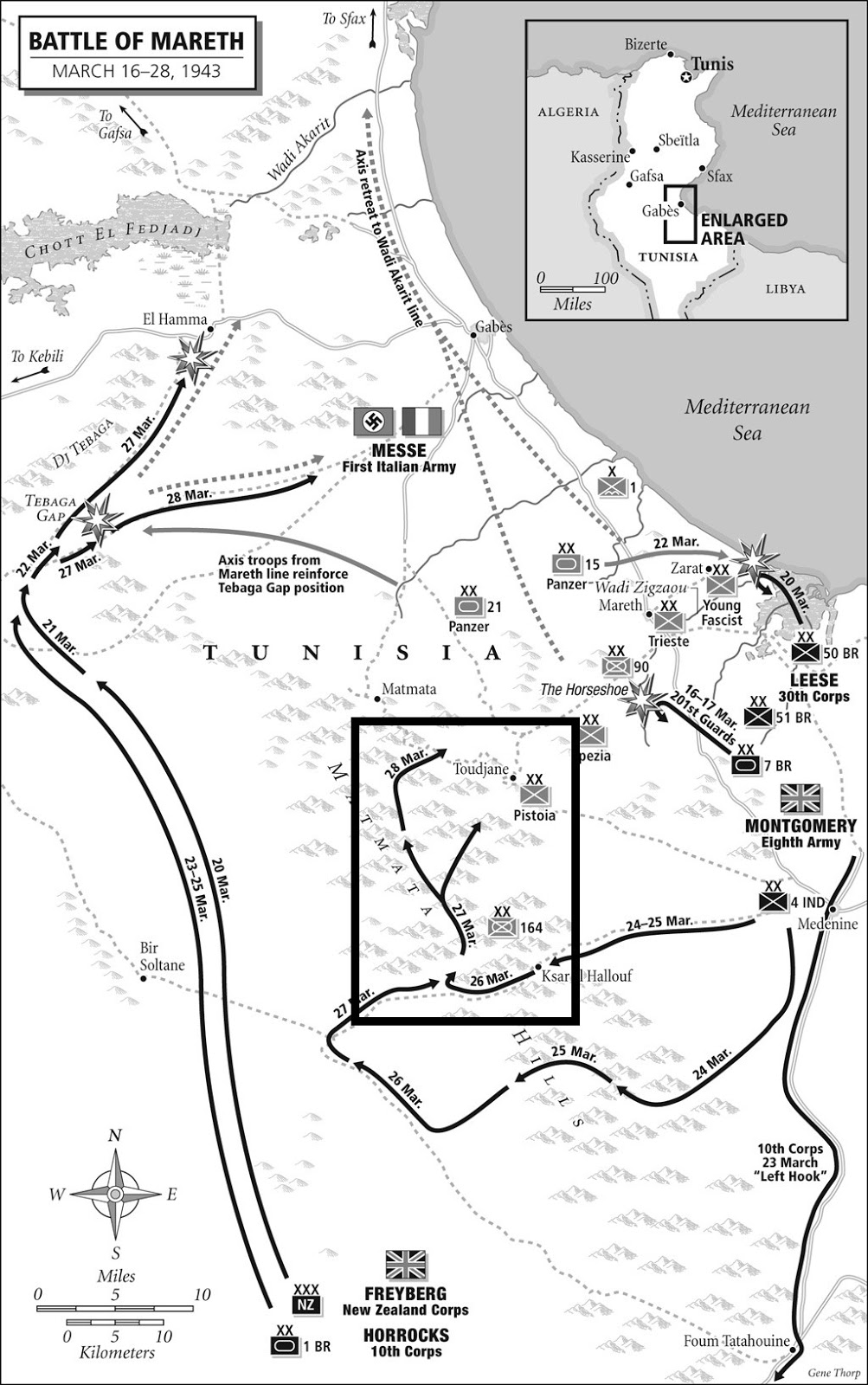

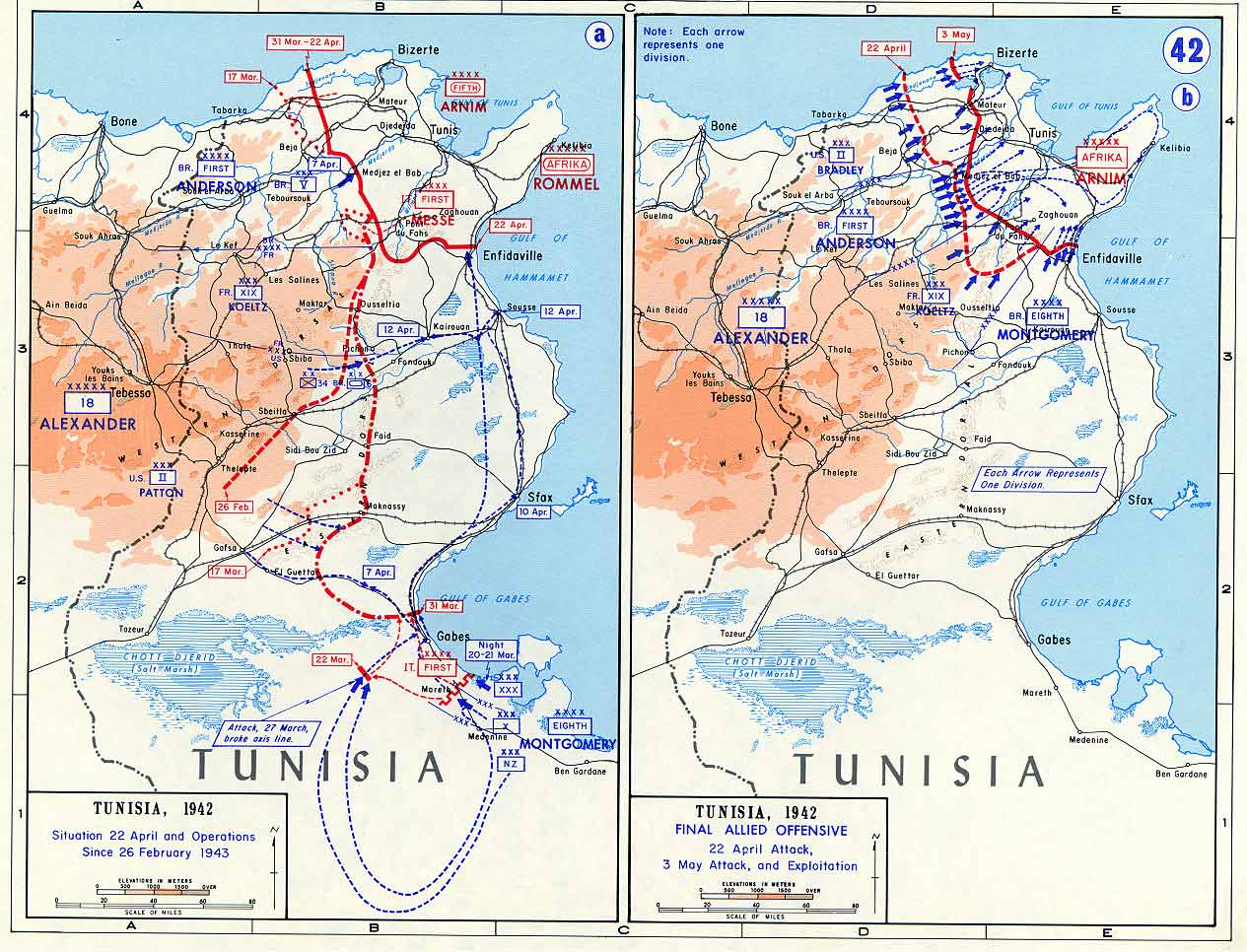

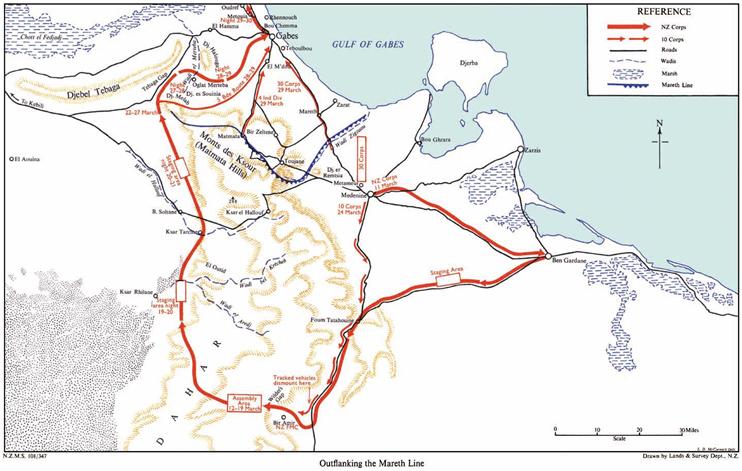

It had originally been hoped that the existence of the New Zealand Corps could be kept concealed from the enemy; the intention had been that it would remain stationary and undetected throughout the daylight hours of 20 March, move on again during the night, and make a surprise attack on the Tebaga Gap – which Eighth Army had renamed ‘Plum Pass’ – on the morning of the 21st. Unfortunately his Intelligence had already warned Messe that a major force would be making for Tebaga, and by the 20th, an ‘Ultra’ interception had revealed to Eighth Army that its secret was out.

Montgomery therefore ordered Freyberg to abandon deception and race for Tebaga as fast as possible. Ahead of Freyberg’s main force, Leclerc’s men seized areas of high ground which might threaten the advance, while a detachment of British sappers with ‘Force L’ prepared crossing-places over the deep dry wadis that lay on Freyberg’s route. This was very necessary, for even as it was, Kippenberger complains that the New Zealanders ‘never did more difficult and tiring marches’. The tank-transporters were particularly liable to be bogged down, on several occasions having to unload their tanks so that these could tow them onto firmer ground. As the New Zealand Corps moved northwards, the terrain became still more difficult, an attack by American bombers did nothing to assist progress, and Freyberg was eventually forced to halt for the night of the 20th/21st March, some 10 miles short of Tebaga.

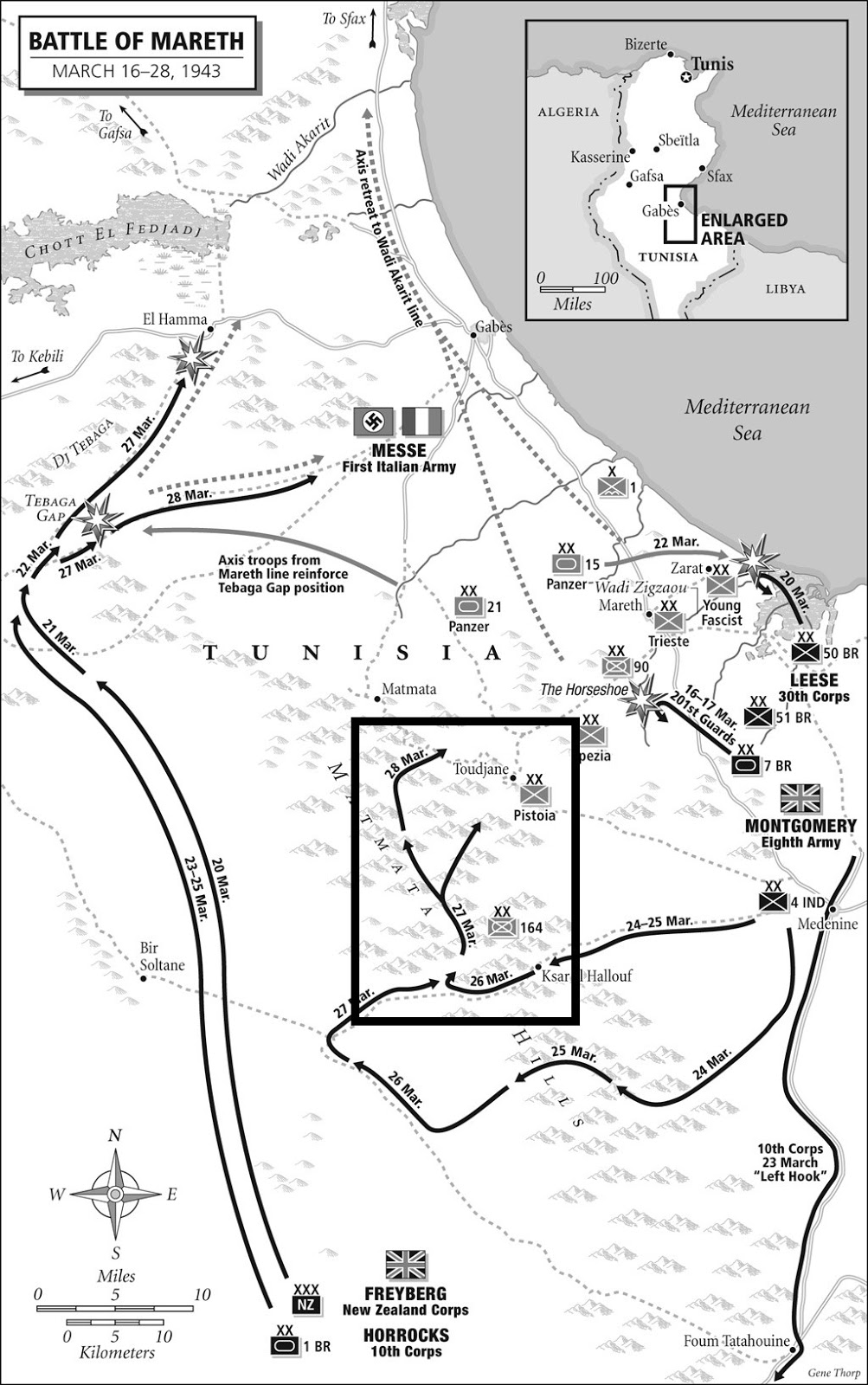

Freyberg’s open advance, Montgomery tells us, ‘would, I hoped, distract attention from the coastal sector’. This is an interesting statement because, with his usual reluctance to admit that all had not gone exactly ‘according to plan’, Montgomery would later emphasize the flanking manoeuvre and ‘play down’ the coastal thrust. It is true that he always intended, as with his advance on Tripoli, that if the enemy should concentrate against one of his moves he would reinforce the other, but his use of the flanking operation to ‘distract attention’ strongly suggests that initially at least he regarded it as very much the less important of the two. Kippenberger, who attended a conference where Montgomery explained his plan to officers down to the rank of lieutenant colonel, also states that his clear understanding was that Montgomery ‘expected the frontal attack to be decisive’; while the Official History unhesitatingly calls the offensive against Mareth ‘the main attack’ as compared with ‘the New Zealand Corps’ subsidiary flanking manoeuvre’.

That the coastal thrust was more important seems certain when it is appreciated that Operation PUGILIST was intended to do far more than just break through the Mareth Line. It will be recalled how Eighth Army had captured the Buerat position, stormed the Homs-Tarhuna defences before the enemy could organize resistance here, and taken Tripoli, all in one continuous series of encounters. Montgomery now aimed to repeat this success, this time capturing the Mareth Line, storming the Gabes Gap before the enemy could organize resistance here, and taking Sfax, the port of Sousse further to the north, and perhaps even Tunis, all in one continuous series of encounters. Yet to do so, he really needed to break through with his coastal attack. As the Official History points out: ‘A successful quick thrust’ at Mareth ‘would have split open the position and crippled the defence, and so would have given the considerable forces of exploitation, and the outflanking New Zealand Corps their opportunity.’

The trouble was that the ‘forces of exploitation’ were too ‘considerable’, while the attackers of the Mareth Line were not strong enough. 30th Corps had three infantry divisions available, yet only 50th British Division was detailed for the attack, and although it would be backed up by the fire of thirteen field and three medium regiments, the only armoured formation in support was 50th Royal Tanks, containing just fifty-one Valentines. 51st Highland and 4th Indian Divisions were held in reserve with the intention of launching them through the bridgehead once this had been secured, while 10th Corps, with 1st and 7th British Armoured Divisions under command, was also kept back, ‘ready’ in the words of its leader, Horrocks, ‘to exploit success towards Gabes’.

Both Montgomery and Leese seem in fact to have paid far more attention to the plans for exploiting success than to those for achieving success. As a result, states the Official History, 50th British Division’s commander, Major General Nichols, ‘was left largely to his own devices’. This was hardly a wise or a fair course of action considering that the division had played only a small part at Alamein and had seen little action thereafter; though Nichols did entrust the initial assault mainly to his more experienced brigade, the 151st.

In other words, Montgomery had committed exactly the same error that Auchinleck had made so often during his infamous five attacks in July 1942: he had been so obsessed with the uses to which victory could be put that he had forgotten the need to win the victory first. This might seem the more surprising as Montgomery had steadfastly avoided this mistake in the past and should have been well aware of the strength of the Mareth Line – apart from the warning given by the action at Horseshoe Hill, he had been well served by offensive patrols, by air reconnaissance, in particular that of ‘his’ two Mosquitos, and by invaluable advice from a number of French officers, including Captain Paul Mezan, a former Garrison Engineer at Mareth.

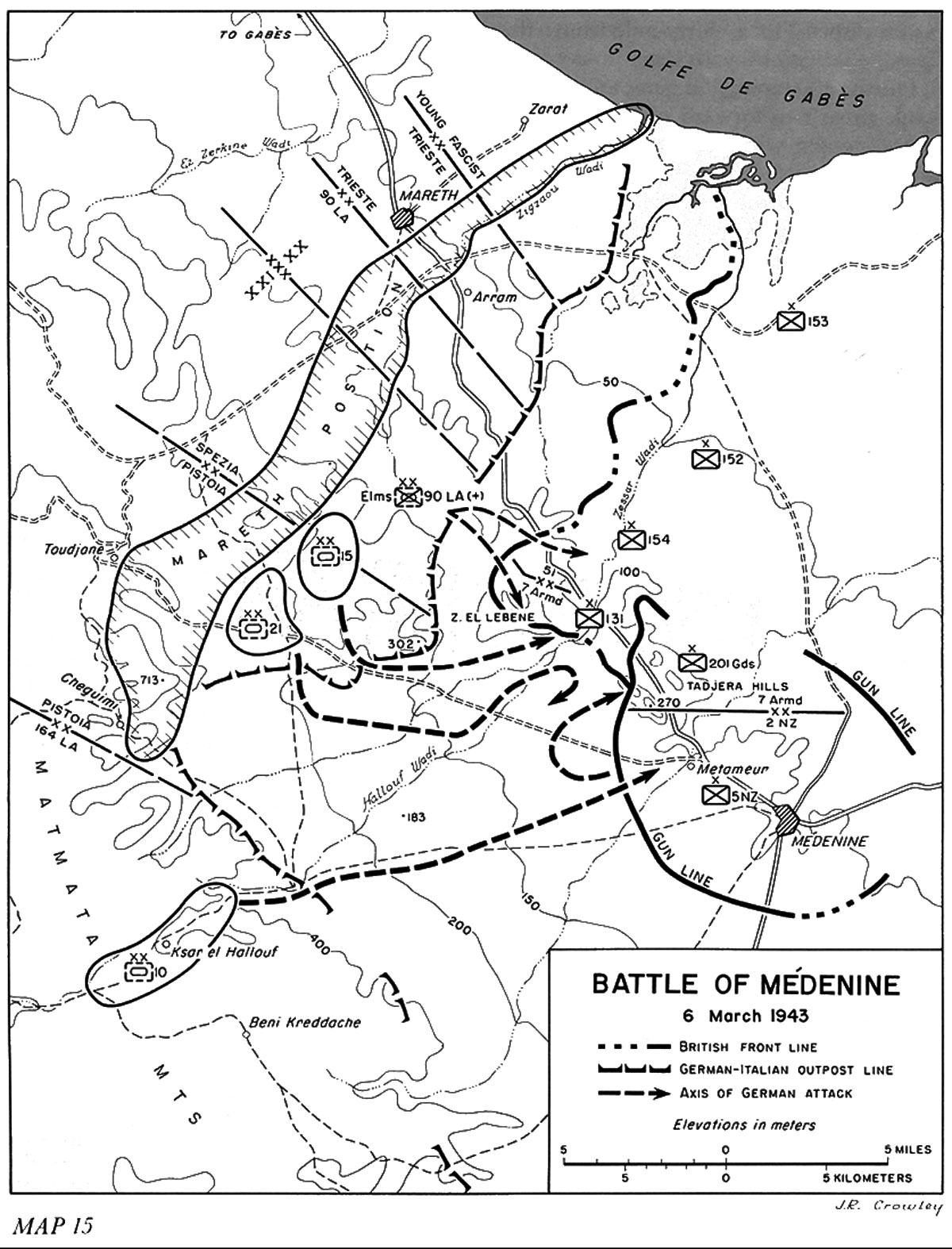

‘Fame, adulation and a growing feeling of infallibility after Medenine,’ declares Nigel Hamilton sternly, had ‘all contributed’ to Montgomery’s over-confidence. So no doubt they had, but the main cause of that over-confidence was quite different – it arose from the fact that Eighth Army had once again received misleading Intelligence from ‘Ultra’.

Thus ‘Ultra’ interceptions had revealed that some of the leading enemy commanders, chiefly Rommel and his successor at the head of Army Group Afrika, von Arnim, favoured a withdrawal from Mareth to the Gabes Gap or even as far as Enfidaville. This tended to suggest a lack of resolution which was quite contrary to reality, since in practice Hitler, Kesselring and even Messe had no intention whatever of abandoning the Mareth Line without a struggle. ‘Ultra’ had also revealed the anxieties of the Italians in particular, which had given Montgomery what Ronald Lewin in his book on this subject, calls ‘a well-founded contempt for the defensive will of the Italians’ – except that in many cases that contempt was not in fact well-founded.

‘It is difficult not to feel,’ Lewin concludes, that it was principally ‘the authority of “Ultra”’ which led Montgomery to believe ‘that an abrupt assault by his infantry, supported by generous gunfire, would “bounce” the Young Fascist and Trieste Divisions into a rapid retreat’. It is indeed, and it may again be noticed that the existence of ‘Ultra’, far from guaranteeing Eighth Army’s success, thus proved a handicap which would bring Eighth Army perilously close to failure.

Eighth Army was also hampered by its usual ill-luck with the weather. This all but prevented the Desert Air Force from carrying out the preliminary operations planned for 19 March, and though happily better conditions prevailed on the 20th, when the coastal thrust was due to commence, on subsequent days the elements would again restrict the aerial support at vital moments. Worse still, heavy rain falling on the Matmata Hills had made the Wadi Zigzaou a still more ‘horrible obstacle’ than the enemy had intended. It now contained a watercourse which in places was thirty feet wide and up to eight feet deep, while the ground underneath the water became soft and treacherous – increasingly difficult for vehicles to cross.

Nonetheless all went well at first. The Royal Air Force Baltimores, the South African Air Force Baltimores and Bostons, and the United States Army Air Force Mitchells kept up raids on the enemy defences all day on the 20th, while after dark, Wellingtons and Halifaxes, accompanied, as at Alamein, by Fleet Air Arm Albacores to drop flares, continued the assaults, and the Hurricanes of No. 73 Squadron, again as at Alamein, roamed ahead to look for targets of opportunity.

Meanwhile at 2230, Eighth Army’s artillery opened fire on the Mareth Line and at 2345, 151st Brigade launched its attack. Ronald Lewin, perhaps feeling the need to mitigate the ill-effects of ‘Ultra’s’ misleading information, argues that Eighth Army, ‘fresh from the open spaces’, was ‘not suited mentally or technically for smashing its way into a stronghold’, but it is not necessary to look to subsequent events at Tebaga or Wadi Akarit to refute this suggestion. The assaulting units, 8th and 9th Battalions, Durham Light Infantry, burst over the Wadi Zigzaou and by morning, despite fierce resistance, had gained a bridgehead about a mile wide and some 800 yards deep and taken a considerable number of Italian prisoners. On their left, 7th Battalion, Green Howards from 50th Division’s other main formation, 69th Brigade, though under heavy fire, stormed a strong forward position threatening the Durhams’ flank, and then held it in the face of repeated counter-attacks, Lieutenant Colonel Derek Seagrim, whose outstanding bravery proved an inspiration to his men throughout the action, earning a Victoria Cross.

It was not the seizing of the stronghold that could not be achieved but the provision of adequate support for the men who had seized it. When the Valentines of 50th Battalion, Royal Tank Regiment moved into the Wadi Zigzaou, the first one stuck fast in the water, bringing the whole advance to a halt. The Royal Engineers, working furiously under artillery, mortar and machine-gun fire, managed to construct another route across the wadi and four tanks passed over this. They carried ‘fascines’, large bundles of wood, tightly bound together, about ten feet long by eight feet high, and these they dropped into the anti-tank ditch on the far side of the wadi and so were able to cross this also. Then came disaster. The next tank to arrive, in the graphic words of General Jackson, ‘broke through the thin crust of the wadi floor and sank up to its turret, totally blocking the crossing’. No further vehicles reached the far bank that night or the next day.

Despite the lack of armour, the men of 151st Brigade, with the aid of further supporting attacks by the Desert Air Force’s light bombers, retained and consolidated their positions during the 21st. Then at 2330, reinforced by their third battalion, 6th Durhams, and by 5th East Yorkshires from 69th Brigade, they resumed their advance, capturing five major strongpoints and further large numbers of prisoners. Meanwhile, during the day, the selfless efforts of the sappers, whose losses were very heavy, improved the crossing over the wadi sufficiently for it to be able to take vehicles again, though they could not construct more than one passage as had originally been hoped.

Indeed at this point the situation in the coastal area looked considerably brighter than that at Tebaga. During the 21st, Freyberg closed up to the entrance to the pass, while the Desert Air Force’s Kittybombers and anti-tank Hurricanes attacked enemy concentrations. That night, Brigadier Gentry’s 6th New Zealand Brigade pushed through minefields to rout the Saharan Group and capture a key enemy outpost at Point 201. Gentry urged that 8th Armoured Brigade should break through the Tebaga Gap forthwith but although Brigadier Harvey had no objections, ‘nothing resulted’ as the Official History relates, ‘because Freyberg had not been enthusiastic’, preferring to wait until dawn.

By then Messe had already taken action. Early on 22 March, 21st Panzer Division arrived from the Axis Army Reserve, being closely followed by 164th German Light Division which Messe had transferred from the Matmata Hills. Freyberg has been accused of missing a great opportunity, but it should be noted that even if he had passed through the Tebaga Gap he would have had to face the full might of 21st Panzer Division in the open, and the New Zealanders, understandably enough, were still very conscious of the perils inherent in such an encounter. Yet whatever Freyberg’s justification, the fact was that the defence of the pass had now come into the hands of 164th German Light Division 's commander, Major General von Liebenstein, and a typically resolute German resistance henceforth barred the New Zealand Corps from any further noticeable progress.

By contrast, at Mareth, Eighth Army, for all Lewin’s comments, had in fact successfully ‘smashed its way’ into the ‘stronghold’ by dawn on 22 March, and the defenders had again suffered during the night from the attentions of the Albacores lighting the way for their Wellingtons and Halifaxes. Moreover the gallant sacrifices of the sappers had by this time cleared the way for reinforcements. Though an enemy counter-attack was a virtual certainty, it appeared that at worst Eighth Army would face an Alamein-style ‘dogfight’ which Montgomery rather welcomed if anything. Yet just when success seemed assured, a series of ill-judged or unlucky steps were taken which would deprive Eighth Army’s soldiers of the rewards earned by their valour.

For a start, Major General Nichols, who was not nicknamed ‘Crasher’ for nothing, had personally crossed the wadi to encourage and hearten his men in the front line – the best place no doubt for a brave and honourable soldier but not for a divisional commander whose Headquarters was left undirected and as a result lost control of the battle.6 The burden of command thus in practice fell on Brigadier Beak and though he was an officer of immense personal courage – the holder of a Victoria Cross – this was the first occasion on which he had directed 151st Brigade in action.

No doubt it was lack of experience which caused Beak to neglect preparations ‘to receive a counter-attack with 6-pounder guns ready … in spite of repeated enquiries from above whether this was being done’, as Montgomery later complained to Alexander.7 Instead he employed the early hours of 22 March in bringing up the remaining Valentines of 50th Royal Tanks. Forty-two of these did pass over the wadi but they so damaged the crossing that no other vehicles, wheeled or tracked, could use it. More heavy rain then fell, making conditions still worse and preventing even the Royal Engineers from rectifying the situation. On the 22nd, Montgomery personally ordered that ‘6-pounder guns and machine-guns must be manhandled across the wadi at once’ – but by then it was too late.

For at 1340, the tanks of 15th Panzer Division’s 8th Panzer Regiment did counter-attack, backed up by the division’s 115th Motorized Infantry Regiment, units of 90th Light – and the elements. Once more Eighth Army was cruelly unlucky with the weather for more heavy rain at the critical moment handicapped the British artillery and even more the Allied airmen. By one further irony, at almost this precise time near El Hamma, which lies to the north-east of the Tebaga Gap, the Hurricane IIDs of No. 6 Squadron were destroying nine tanks from 21st Panzer Division; but at Mareth, the Desert Air Force’s light bombers which might have delivered, and were preparing for, a much more powerful blow against 15th Panzer Division, were grounded by the downpour.

The Valentines of 50th Royal Tanks did everything possible to resist the enemy onslaught but in vain. Much stress has been laid on the fact that only eight of them had been uprated to carry a 6-pounder, which meant that all the others were out-gunned by Messe’s 10 Mark III Specials and even the eight were outgunned by the long-barrelled 75mms carried by Messe’s fourteen Mark IV Specials. The British armour was thus far more genuinely inferior to that of the enemy than on most earlier occasions on which a similar excuse is put forward. Yet it was the absence of those anti-tank guns which had broken the panzers’ attacks at Alam Halfa, at Alamein and most recently at Medenine, that really crippled the defence. No one was more aware of this than the armour’s CO, Lieutenant Colonel Cairns, who throughout the morning of the 22nd had been pleading that anti-tank guns be sent forward – but the Wadi Zigzaou remained impassable.

By contrast the Germans did have anti-tank guns available, which as usual were handled more boldly and more brilliantly than their armour. These knocked out three Valentines before the panzers fired a shot. Throughout the day, 50th Royal Tanks kept up the fight but by nightfall, thirty Valentines had been destroyed, Cairns was dead, and his successor in command, Major Maclaren, had withdrawn the remains of his force to the edge of the wadi.

The British infantrymen were also in trouble. Three of the captured strong-points were lost again, and casualties mounted. At midnight, the Germans put in a new attack and 50th Division was once more driven back. At 0200 on 23 March, Montgomery was aroused from sleep to be told by Leese that Eighth Army’s bridgehead had been virtually eliminated.

Chapter 12

THE LEFT HOOK

On hearing this news, Montgomery’s cool self-confidence deserted him for once – and paradoxically this fact is a supreme tribute to his generalship. At Alamein, when Montgomery had been awakened to hear pleas by his subordinates that his attack be called off, he had curtly refused. Almost any other commander, recalling this earlier incident, would have been tempted to think that once more all that was needed was a bit of resolution, and have insisted that 50th Division keep up its pressure. It is very much to Montgomery’s credit that he realized instinctively that this time the situation was very different.

The point was that this time Montgomery was personally worried by the situation, particularly the failure to bring the 6-pounder anti-tank guns into the front line – hence the ‘repeated enquiries from above whether this was being done’. For the moment he ordered Leese to hold fast in the bridgehead to the best of his ability but he clearly recognized that this could only be a temporary expedient, and at 0900, he called another conference at which he told Leese that the coastal thrust would be abandoned. During 23 March, the light bombers of the Desert Air Force made no less than ten raids against enemy positions, but these were designed to protect the British troops from further molestation, not to assist a renewed advance. That night, under cover of a heavy artillery barrage, the surviving tanks and infantrymen fell back over the Wadi Zigzaou. 151st Brigade alone had suffered some 600 casualties.

Montgomery’s anxieties had already prompted him to ask Alexander whether 2nd US Corps – now commanded by Patton – could assist him by striking at First Italian Army from the rear. As was mentioned earlier, the Americans were ideally placed to trap Messe’s men either by breaking through the Maknassy Pass or by advancing from Gafsa which they had reoccupied without resistance on 17 March. Alexander did request Patton to push forward strongly in both these areas, but his doubts whether this would prove effective were quickly realized. Patton’s 88,000 men were opposed by only some 1,000 Germans and 7,000 Italians, backed by the forty tanks of 10th Panzer Division and the obsolete Italian armour with the Centauro Division; yet a series of attacks starting on 22 March all met with failure, though at least they prevented the Axis forces resisting them from adding to the numbers facing Eighth Army.

The American assaults also greatly alarmed von Arnim, who appears to have inherited Rommel’s pessimism as well as his post at the head of Army Group Afrika. Fearing that First Italian Army might be cut off as Montgomery envisaged, von Arnim issued instructions that the defenders at Mareth should begin to withdraw on the night of 25th/26th March, covered by von Liebenstein’s troops at Tebaga, and be back in the defences of the Gabes Gap by the 28th.

These orders would later lead Patton, whose arrogance was certainly no less than that of any other officer of any nation, to claim that it was really he who had ‘won Mareth’ for Eighth Army; but his contention overlooks the point that von Arnim’s views were rejected by his superiors and in particular by the unquenchable Kesselring. On the afternoon of 24 March, by which time of course 50th Division had already retired across the Wadi Zigzaou, Kesselring arrived at Messe’s HQ. Here, as the Official History makes clear, he firmly ‘pronounced against withdrawal’. Next day, he also ‘visited the Tebaga sector and reported to von Arnim that von Liebenstein was not in immediate danger’. In addition Messe, ‘encouraged by Kesselring’, sent a written report to von Arnim recommending that the retirement to the Gabes Gap ‘be postponed’ and Tebaga ‘reinforced’. Von Arnim provisionally ordered that the retirement should be delayed until the night of the 26th/27th March, but Messe’s actions on the 25th scarcely indicate any intention to withdraw at all; on the contrary he now sent 15th Panzer to an area south of El Hamma, ready to reinforce 21st Panzer and 164th German Light Divisions at Tebaga should the need arise. During the 25th also, Patton’s final attacks were broken, thereby proving that von Arnim’s fears had been groundless.

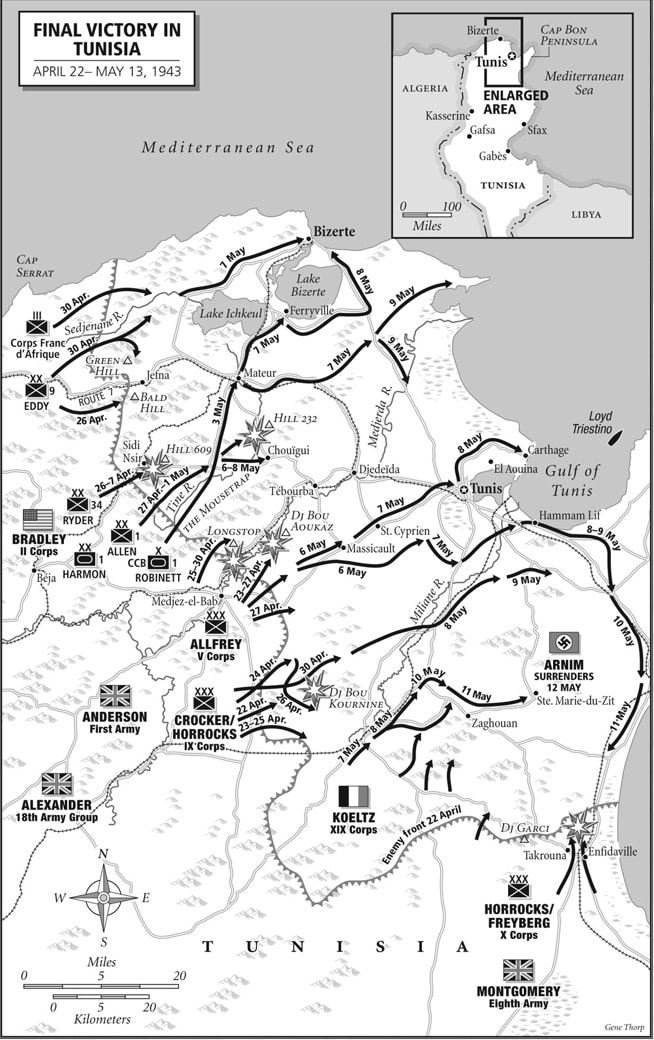

The danger to First Italian Army would in fact come not from 2nd US Corps but from Eighth Army. When Montgomery held his conference at 0900 on 23 March, he had, as General Richardson relates, ‘recovered his “poise”’. His orders to de Guingand, Leese and Horrocks, all of whom were summoned to attend, were to set in motion what Ronald Lewin would call ‘the brilliant outflanking move by the New Zealanders and 1st British Armoured Division which levered General Messe’s army back into Tunisia’. In Eighth Army it would become known simply – and very appropriately in a battle code-named PUGILIST – as ‘The Left Hook’.

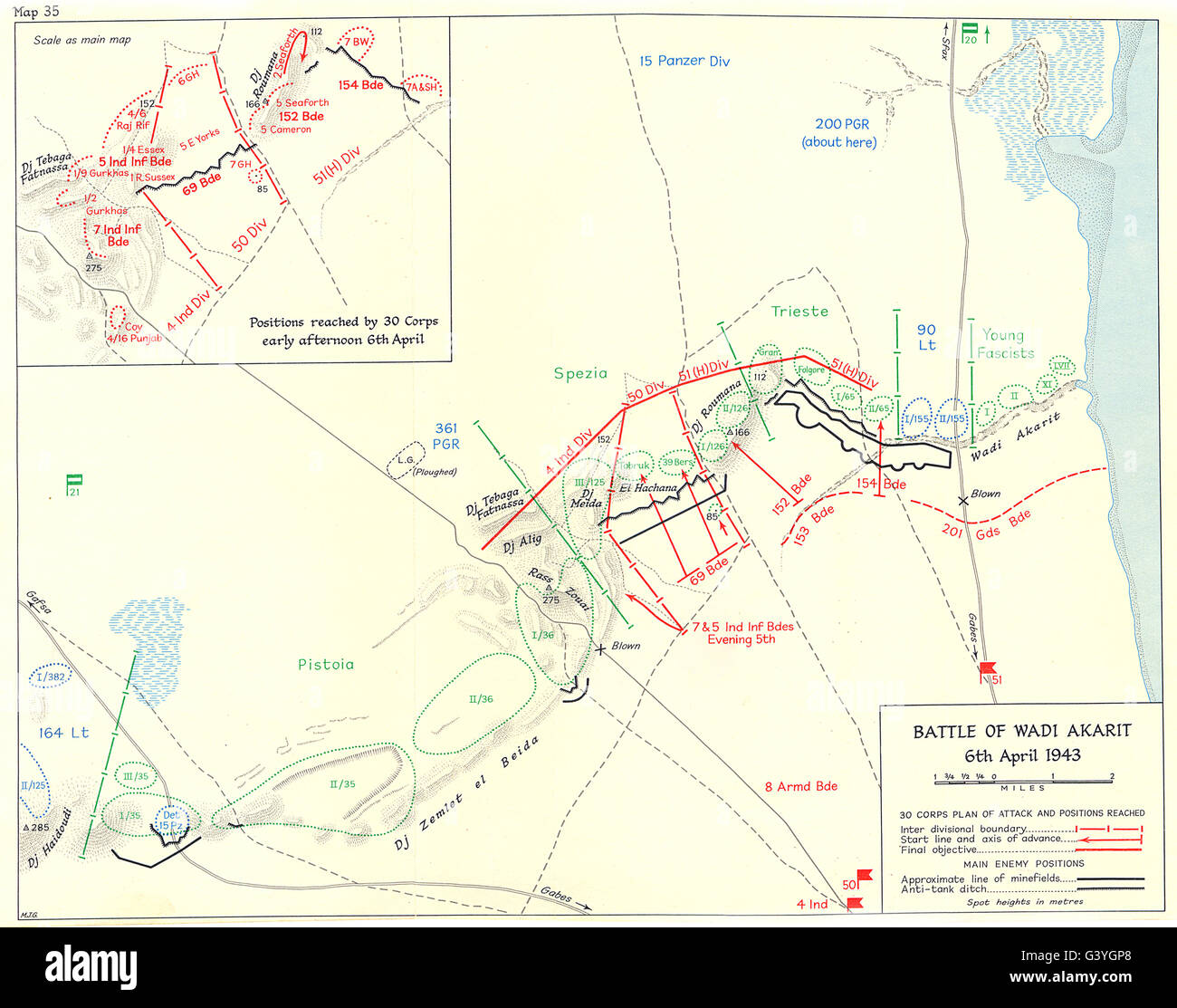

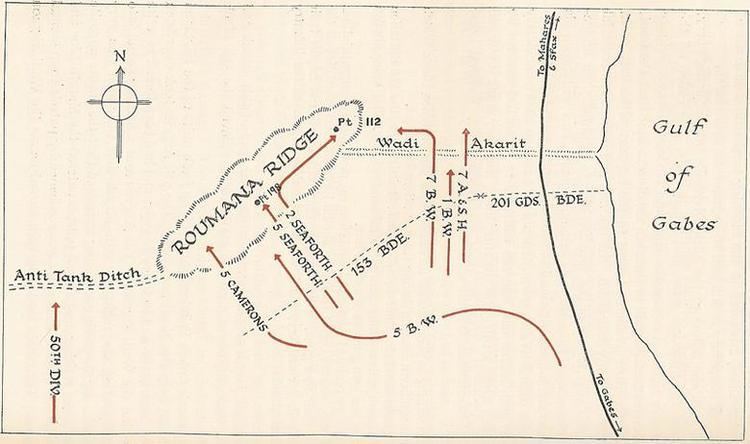

In fact two moves were set in train. One was by forces from 10th Corps, chiefly 1st British Armoured Division under Major General Raymond Briggs, through Wilder’s Gap to join Freyberg. The other was by Tuker’s 4th Indian Division from 30th Corps due westward into the Matmata Hills, taking advantage of the withdrawal of 164th German Light Division to Tebaga. Its tasks were first to clear the Hallouf Pass the use of which would provide a much shorter route by which to get supplies to the forces at Tebaga, and then to head northward through the hills with the object of outflanking the Mareth Line in this area also, thereby putting still more pressure on its defenders.

When Montgomery had first learned of 50th British Division’s repulse at 0200 on the 23rd, he had spent more than an hour discussing with de Guingand the prospects of strengthening the New Zealand Corps. Consequently when the 0900 conference broke up, the Chief of Staff was able to begin at once to put the necessary steps in hand. There were, however, a considerable number of these, chiefly the provision of transporters for the tanks of 2nd Armoured Brigade, now once more commanded by Brigadier Fisher, which formed the cutting edge of 1st Armoured Division, and the arrangement of anti-aircraft protection. In addition, as after Alamein, there was the confusing circumstance of two different corps trying to advance over the same area.

As a result, neither 1st British Armoured nor 4th Indian Division could set off until late on the 23rd. 7th Indian Brigade which was ordered to attack the Hallouf Pass from the south-west was then able to embark on its mission without further delay, but 5th Indian Brigade, the task of which was to clear the pass from the east, and 1st Armoured Division both arrived at Medenine at the same moment on converging lines of march, causing a tremendous ‘traffic jam’ which cost a good deal of valuable time.

Fortunately little real harm was done except to strained nerves. On 26 March, 4th Indian Division secured Hallouf Pass, though in practice the route through this was scarcely needed. Lieutenant Colonel Robert Scott had already led his 4th Battalion, 6th Rajputana Rifles northward through the hills, and the remainder of 5th Indian Brigade now followed, and was in turn followed by 7th Indian Brigade which had been much hampered by extensive minefields. Enemy resistance proved understandably slight for on 27 March, a general Axis retreat was ordered as a result of dramatic events elsewhere – ironically 4th Indian Division would probably have met with far greater opposition had it not been delayed by the ‘traffic jam’. But the natural obstacles and the mines proved a more than sufficient handicap on their own and it was not until the morning of 28 March that Tuker’s men emerged from the hills and successfully outflanked the Mareth Line – only to find that it had already been abandoned by German and Italian forces.